Boundaries of an Oncologically Appropriate Neck Dissection

Superficial or Total Parotidectomy

Removal of a Sufficient Number of Lymph Nodes for Adequate Staging

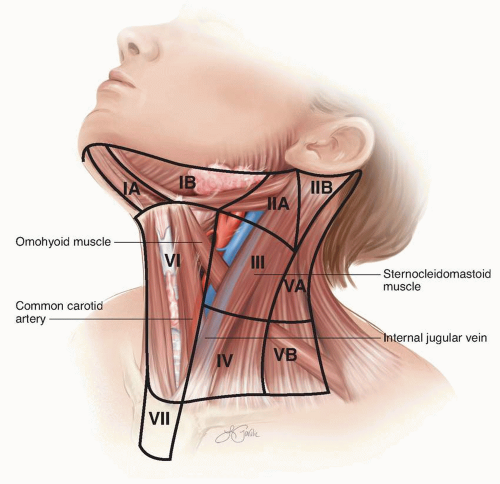

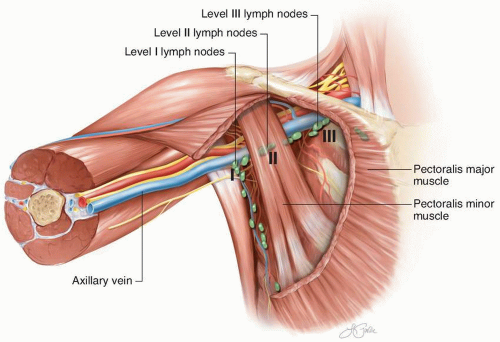

node basins. As noted in chapter 9, the addition of single photon-emission computed tomography and computed tomography (SPECT/CT) to traditional two-dimensional planar lymphoscintigraphy can be very helpful in identifying both traditional and discordant lymphatic drainage patterns in the head and neck.115 The standard nodal basin levels of the neck with corresponding anatomic boundaries are defined in Table 10-1 and illustrated in Figure 10-1.

TABLE 10-1 Anatomic Boundaries of Nodal Basins by Level | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 10-2 Appropriate Levels for Selective Neck Dissection Based on Primary Tumor Site | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

not be to obtain a minimal number of lymph nodes. Instead, the total number of lymph nodes removed can serve as a surrogate quality metric for the adequacy of the lymphadenectomy. There are two components to this quality metric. The first is the anatomic extent of the lymphadenectomy performed by the surgeon. The second is the completeness of the pathologic assessment of the specimen, including identification and examination of all available lymph nodes.

Removal of Level I, II, and III Lymph Nodes

Removal of a Sufficient Number of Lymph Nodes for Axillary Staging

goal is prognostication, because the total number of positive lymph nodes is a predictor of the risk of developing distant metastatic disease.

FIGURE 10-2 Standard axillary lymph node levels in relationship to the pectoralis minor muscle and other axillary structures. |

the supra-axillary fat pad are routinely removed as part of this lymphadenectomy. The interpectoral lymphoareolar tissue sits between the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor muscles. Laterally, the median pectoral neurovascular bundle can be divided to facilitate anterior retraction of the pectoralis major muscle. During removal of the interpectoral nodes, care is taken to avoid injury to the lateral pectoral neurovascular bundle located medially, which can lie anterior to a portion of the medial aspect of the pectoralis minor muscle. Injury could result in complete denervation of the pectoralis major muscle.

muscle. In this case, the pectoralis minor muscle is often dissected free circumferentially and retracted with an instrument or a Penrose drain.

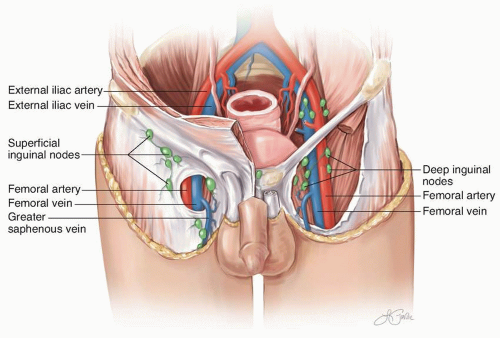

Resection of Superficial Groin Lymph Nodes

Removal of a Sufficient Number of Lymph Nodes for Inguinal Staging

Resection of Deep Groin Lymph Nodes

Sartorius Muscle Rotation Flap

Minimally Invasive Groin Dissection

FIGURE 10-4 The inguinal lymph nodes and their relationship to anatomic landmarks, including the inguinal ligament and the femoral vessels. |

lymphedema, scientific data to support this assumption with melanoma lymphadenectomy are lacking. If preservation of the saphenous vein is being considered, then it is oncologically important to remove all of the surrounding lymph node-bearing tissue.

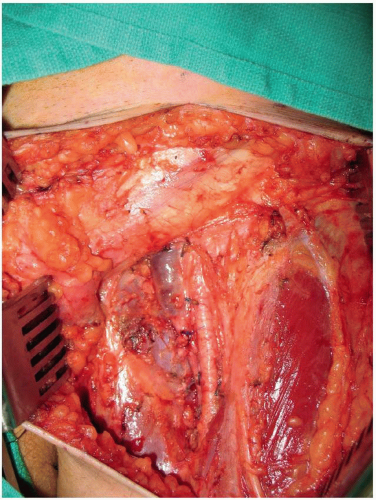

FIGURE 10-5 A completed left superficial groin dissection with removal of the lymphoareolar tissue overlying the lower abdominal wall, inguinal ligament, and the femoral vessels. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree