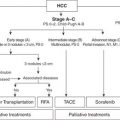

Liver Transplant

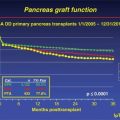

Liver transplant is considered the most effective method to treat both the cancer and the underlying liver disease from which most HCC develop. Therefore a productive relationship between oncology (surgical and medical) and transplant is required to maximize this option for appropriate patients. Transplant eligibility is based on the size and number of tumors, and criteria have been established to optimize cancer-specific outcomes. Most commonly used worldwide are the Milan criteria in which patients with up to three foci of HCC less than 3 cm or one tumor less than 5 cm are eligible for liver transplantation. These patients experienced 5-year overall survival (75%) that paralleled survival observed in patients transplanted without cancer at that time. Other centers, such as The University of California San Francisco (UCSF), have broadened criteria (one tumor <6.5 cm or two to three tumors, none >4.5 cm, with the total tumor diameter not to exceed 8 cm) for eligibility based on outcome-based evidence that less strict parameters do not adversely affect overall survival with the development of more sophisticated liver-directed therapies (LDTs) for HCC, and down-staging of patients into either Milan or UCSF criteria has emerged as a reasonable approach to select patients. What has become apparent is that progression of disease despite LDTs identifies cancers that are at high risk for recurrence after transplant. Demonstration of a response to LDTs prior to transplant in combination with surveillance over a period of time prior to committing to transplant allows centers to select out more favorable biology and broaden patient eligibility without compromising cancer-specific survival.

Surgical Resection

Liver resection remains the gold standard for patients with resectable HCC that develops in the setting of normal liver. However, most patients with HCC have diseased liver parenchyma, and resection in this population is more fraught with potential for complications. For this reason, preservation of liver parenchyma is critical, and treatment requires a balance between the effect of any surgical intervention short of transplant and the potentially detrimental effect of this treatment on a vulnerable and “high-risk” remnant. Most published resection series focus on patients with single tumors or limited disease burden up to a certain size and well-preserved (Child A) function. As LDTs have improved, the gap in overall survival between LDT and resection in patients with underlying liver disease has narrowed substantially. This is in part due to the high rate of recurrence or de novo tumor emergence in the liver remnant. The recurrence rate after resection is approximately 50% at 2 years and 75% at 5 years in most series. Institutional treatment paradigms with respect to resection versus transplant should be established with input from both transplant and surgical oncology since transplant eligibility may come into play with either recurrence after resection or in the event that the patient struggles with liver insufficiency postoperatively.

In regions of the world where hepatitis B is the dominant risk factor for cancer, resection is employed more commonly for several reasons including the following: (1) cadaveric organ availability is limited; (2) centers outside the United States rely more on living related donor pools where the human investment in the process is greater; and (3) a higher proportion of patients with hepatitis B have preserved liver function making resection safer. Therefore, to minimize unnecessary risk to a living donor and help select patients whom would most benefit from a liver transplant, resection is used up front with transplant reserved as a salvage option in the event that the cancer recurs or the liver function worsens over time.

The natural history of HCC in the background of NASH would suggest a higher proportion of noncirrhotic patients and a lower rate of recurrence (or de novo tumor emergence) than either hepatitis B or hepatitis C. For this reason, resection may emerge as a reasonable option in this patient population as well. Resection versus transplant in NASH patients must be evaluated based on underlying liver reserve.

Embolization

Most patients are not candidates for resection or transplantation at the time of diagnosis because of either the extent or the distribution of tumor, underlying liver function, or medical comorbidities. Interventional radiology has played a central role in the treatment of HCC for decades. For this reason, engagement of interventional radiology is critical to adequately address the range of HCC patients within a robust liver oncology program. The dual blood supply to the liver has allowed the development of hepatic artery–based therapies over the past 30 years. Whereas non–tumor-bearing liver parenchyma receives nutrient supply predominantly from the portal vein, most HCC are supplied predominantly by the hepatic artery. Catheter-based techniques take advantage of this unusual architecture to deliver intra-arterial therapy directly to tumor bed. Several different treatments have been administered by catheter via the artery to treat HCC, including bland embolization, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads (DEB), and radioembolization. To date, there have been no prospective or randomized trials defining any of the available options as superior in terms of survival. Centers around the world have therefore gravitated toward the technique that works best in their hands. Complications common to all catheter-based therapies for HCC include postembolization syndrome (fever, nausea, and pain), nontarget embolization (stomach, gallbladder, duodenum, pancreas), and liver failure (<2% in well-selected patients).

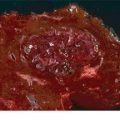

Bland Particle Embolization

Bland particle embolization is based on the unique dependence of HCC on the hepatic artery. Small particles (40 to 120 μm) are injected into the tumor arterial supply to cause terminal vessel blockade and resultant ischemic necrosis. The 5-year data on response and survival suggest comparable cancer-specific outcomes to other catheter-based techniques. The results of bland embolization are essentially immediate, and radiologic evidence of tumor necrosis is seen within hours of the procedure. This is a particularly useful feature in patients who present with significant tumor burden where further progression may render them untreatable. Other theoretical advantages of bland embolization include (1) the particles come in a range of sizes that can effectively address unique vascular characteristics of the tumor, including intrahepatic portal–systemic shunting; (2) lower periprocedural cost; (3) no delay between initial arteriogram and treatment delivery; (4) no chemotherapy or radiation-related side effects; (5) the ability to retreat due to better preservation of intrahepatic arteries after treatment; and (6) less institutional infrastructure requirements such as radiation safety.

Chemoembolization/Drug-Eluting Beads

Doxorubicin-eluting beads are another catheter-based LDT. The use of an eluting bead is considered an improvement on conventional chemoembolization (TACE) in which hydrophilic chemotherapeutic agent(s) (with or without Lipiodol) was injected into the liver via the hepatic artery. To prevent washout of the chemotherapy from the tumor bed and thereby allow prolonged contact between chemotherapeutic agent(s) and tumor cells, the feeding artery was then occluded with particles or Gelfoam. Conventional TACE has largely been replaced by embolization with DEBs. DEBs are preformed deformable microspheres that are loaded with doxorubicin up to 150 mg per treatment. The pharmacokinetic profile of the DEB is significantly different from that seen with conventional TACE, with evidence that the peak drug concentration in the serum is an order of magnitude lower for DEBs compared to TACE. Objective response by EASL criteria has been reported to be 70% to 80%. One- and 3-year survival rates of 89.9% and 66.3%, respectively, have been reported in a heterogeneous cohort of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) A–C patients. The advantages of DEB overlap with those related to bland embolization: (1) the ability to treat multiple tumors in different regions of the liver during the same procedure; (2) the use of superselective techniques limits toxicity to normal liver substance; and (3) the ability to repeat the procedure several times over the lifetime of the patient.

Radioembolization

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree