- A comprehensive approach to diabetes prevention and care includes policies and activities outside the formal health sector, particularly for primary prevention.

- Integrated care refers to the need to provide care for conditions coexisting with diabetes within the same primary health care service.

- Continuity of care, a cornerstone of effective health care organization, is associated with improved outcomes.

- Prerequisites for improving outcomes include ensuring that essential medications (including insulin) are either free or highly affordable and that tests for the diagnosis of diabetes, monitoring of control, and equipment to screen for complications are available.

- Living health systems should care for, empower and nurture their staff so that they are enabled to do the same for their patients.

- If no one is responsible for chronic care, the tendency is for it to be overlooked.

- A less qualified professional may offer lower quality care, but there is potential for effective substitution, with the right training and organization.

- A respectful, open and curious stance may help different professionals and people to understand each other better.

- Patient-centeredness improves quality of life, increases patient satisfaction, improves adherence to treatment, enhances the integration of preventive and promotive care, and improves the provider’s job satisfaction.

- In low resource settings where large numbers of patients overwhelm facilities, it may make sense to extend care into the community.

- Ideally, a systematic process for reviewing the evidence and updating guidance accordingly should be in place in all countries.

- Advances in the usage of information technology and the internet are likely to provide increasingly important contributions to diabetes care both in well-resourced and less-well resourced settings.

Introduction

Almost no community worldwide remains unaffected by diabetes. Premature mortality and an array of complications, in particular the chronic complications, result in a considerable impact that is experienced by individuals, families and societies. This impact is predicted to increase, primarily in countries such as those in North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. In these countries, lifestyles are transitioning and the populations consume less healthy foods, and have rising levels of physical inactivity and obesity.

Enormous inequalities exist in the provision of health care for people with diabetes, in keeping with the widely disparate socioeconomic status that prevails globally. These inequalities are not only found between countries, they occur within countries, for example in rural-versus-urban settings, private-versus-public sectors and hospital-versus-community-based services. Considerable challenges face health planners and providers, especially in less well resourced countries and areas countries, because of the traditional infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and malaria, coexisting with HIV/AIDS, and the emerging scourge of chronic diseases, including diabetes, producing a multiple disease burden with competition for limited resources. Furthermore, most health care systems have evolved from the basis of dealing with acute medical problems and have been or, in most instances, remain ill-equipped to provide the kind of care that people with chronic diseases require.

That is not to say well-resourced countries do not face challenges with health care delivery. In these countries, there are also problems in ensuring that quality health care is delivered in a cost-effective manner. Notwithstanding these challenges, each person with diabetes, wherever they live, should have access to the best care that can be provided in their setting and consequently have the opportunity to achieve the outcomes they seek. Unfortunately, this is not the current situation, even in well-resourced countries and settings. The United Nations Resolution on Diabetes “Encourages member states to develop national policies for the prevention, treatment and care of diabetes in line with the sustainable development of the health-care systems, taking into account the internationally agreed upon development goals, including the Millennnium Development Goals” (Resolution 61/225, December 20, 2006). The resolve of the United Nations, together with the policies and influence of the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) and the World Health Organization (WHO), need to be harnessed in order to improve the suboptimal care and outcomes for people with diabetes. After all, it is not that a dearth of evidence exists for the effectiveness of a wide range of interventions to prevent complications associated with diabetes, but rather the reverse. Narayan et al. [1] have identified three interventions that are cost-saving and fully feasible in terms of penetration of the target population, technical complexity, amount of capital required and cultural acceptability, even in low and middle income countries and across all regions:

A fourth intervention, pre-conception care, was found to be cost-saving, but not fully feasible because of concerns of not being able to reach all women with diabetes.

The issue at hand is how to translate the evidence into practice and thus reality, acknowledging that, almost without exception, health services are in need of repair and the specific interventions to be introduced or implemented will undoubtedly vary depending on the health care structure and resources available. There is also the need to recognize that diabetes requires that people not only have access to sufficient resources, such as medication, but also the understanding, motivation and skills to self-manage their condition.

Health care cannot be seen in isolation, occurring as it does within a broad societal framework which places varying degrees of emphasis on ensuring that quality care is prioritized. Thus, in the first instance, for effective health care delivery, a positive policy environment needs to be in place, nationally and locally. The “macro” level of the WHO Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions (ICCC) framework focuses on this very issue (Figure 58.1), highlighting the components that can promote a positive policy environment [2]. Political will, building or strengthening partnerships (e.g. between community-based organizations, patient organizations, health care workers and government), and ensuring consistent funding are key aspects of the process. So too is the need for an inter-sectoral approach or collaboration to building a healthy society, encompassing, for example, urban planning (with the provision of green areas, easy public transport, access to sport and recreation facilities), the introduction of health promotion activities within schools and the food industry.

The “meso” level in the ICCC framework relates to health care organization and links to the community. It is at this level that the concept “model of care” comes into play. As coined by Davidson et al. [3], a health care model can be regarded as an overarching design for the provision of a service that is ideally underpinned by a theoretical framework, evidence base and clearly defined standards. The model has core principles and elements in addition to an agreed upon agenda for implementation and later evaluation. It is unlikely that a single health care model for diabetes exists that can be used effectively and efficiently in all settings – indeed, the model will take different forms or shapes in different settings. Health planners have to decide whether to pursue a diabetes-specific model of care or to incorporate multiple chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension and chronic lung diseases in a common chronic care model. There are salient reasons for pursuing the latter, given the commonality of aspects of care for these conditions, but factors such as the available resources are likely to guide this decision. Regardless of the model selected, changing the value system in which health care is delivered, with the aim of ensuring motivated affirmed health care workers, is perhaps key to equipping or enabling people living with diabetes with the information, motivation and skills to self-manage their diabetes. There is a real need to embrace the lessons that can be learned from the successful highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) programs for people with HIV/AIDS, which have yielded levels of adherence to therapy that most clinicians and public health specialists can only dream of in relation to diabetes [4].

There are certain core principles for diabetes care that could be applied across all resource settings [2]. These include establishing:

- A comprehensive approach that provides for health promotion to enable prevention and early diagnosis, management of diabetes and complications when they arise and rehabilitation when needed.

- Integrated health care, such that conditions coexisting with diabetes, can be readily managed within the same primary health care service.

- Continuity of care, which has a number of connotations: in terms of the relationship between health care worker and patient; in terms of management strategies and decision-making; and in terms of patient information.

- Access to care, which can be understood in a physical or geographic sense, but extends to access to appropriate equipment for monitoring, diagnosis and management as well as medication.

- Coordination of care from primary to secondary and tertiary levels, with appropriate referral strategies and role delineation. Where multiple professionals and organizations are involved in primary care, horizontal coordination of care is also important.

- Teamwork: diabetes care involves multiple health workers, professional categories and disciplines, even in low resource settings. Establishment of teams whose focus is on delivering and improving the quality of care permits the development of shared goals, defining and clarifying roles, reflecting on how care can be improved and holding each other accountable for decisions. The identification of a team leader may be a major factor in the success of this element.

- Person-centeredness implies a more collaborative approach and holistic understanding of the patient that elicits, acknowledges and addresses relevant beliefs, concerns and expectations. This is at least partly a paradigm shift in the mind of the health worker from the traditional biomedical, technical and sometimes authoritarian model to a biopsychosocial, holistic and participatory model.

- Family and community orientation are integral to provide support for the individual with diabetes as well as to raise awareness and to extend care from the health centers into the community.

- The use of evidence as far as it is available, accessible and relevant. The evidence base for diabetes is constantly expanding and all resource settings need to look at how they access the latest and ever-changing evidence base.

We now discuss how these principles are being incorporated into care for people with diabetes across different resource settings; low and middle income settings such as encountered in most low and middle income countries as well as in high income countries. Finally, how information technology can be embraced and harnessed appropriately in different settings with the goal of supporting these principles is explored.

A comprehensive approach

Taking a comprehensive approach to diabetes prevention and care implies that polices and activities are put in place to address primary prevention, early diagnosis (including screening if appropriate), management of diabetes and its complications, and rehabilitation for those affected by complications. A comprehensive approach will include policies and activities outside the formal health sector, particularly for the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). For example, promoting healthier diets and greater physical activity could involve policies on food production, marketing and taxation, and policies on design of local environments and public transport. The WHO’s strategy on diet and physical activity provides a framework for developing national and international policy that is relevant to countries at all levels of development [5]. The best indication of a comprehensive approach is a national government-led strategy that covers primary prevention through to rehabilitation, with the caveat that the presence of a strategy does not guarantee that it has been implemented. A recent survey carried out through IDF member organizations [6] found that of the 98 countries from which responses were received, just over 70% claimed that their country had implemented a national diabetes program. The region with the lowest proportion of countries (30%) with a national diabetes program was sub-Saharan Africa, but even in richer regions, such as Europe, over 20% of responding countries did not have a national diabetes program. Examples of national diabetes programs in countries at opposite ends of the economic spectrum include the program in Cameroon [7] and the National Service Framework for Diabetes in England [8].

Integrated health care

Integrated care for people with diabetes refers to the need to provide care for conditions coexisting with diabetes within the same primary health care service. Within most high income countries, primary health care has been developed to provide a range of services covering most of the needs with people with diabetes, and indeed with other chronic conditions. In low and middle income countries, however, integration of care is often a challenge, as donor funding is most often given to specific disease programs such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis or malaria, or large-scale government funding is allocated for specific vertical programs, such as HIV/AIDS. For example, in Zambia the donor funding for HIV/AIDS is larger than the total health care budget. While this funding enables higher quality care for a specific disease it can weaken the health care system as a whole. Further, disease-centered programs, through higher salaries and better working conditions, may draw professional staff away from primary care. Therefore, initiatives aimed at strengthening an approach to diabetes should do this with an integrated model of care and with the goal of strengthening the whole approach to chronic care [9,10]. An example of an integrated chronic care clinic for HIV/AIDS, diabetes and hypertension at provincial hospitals in Cambodia has recently been reported (Box 58.1) [11]. There is no reason why such an approach could not be used in primary health care [12].

Chronic disease clinics for the combined care of HIV/AIDS, diabetes and hypertension were set up in two provincial referral hospitals in Cambodia based on a number of assumptions: a common approach is needed to respond to the needs of chronic disease patients, with the widespread acceptance that HIV/AIDS has become a chronic disease following increasing availability of antiretroviral therapy; attending a combined clinic would minimize the stigma that a specific HIV/AIDS clinic induces; and that the care model should reflect estimates of disease burden. All patients were managed according to standard treatment protocols. A team of counselors promoted adherence and lifestyle changes to complement medical consultations, and peer support groups extended the efforts of the doctors and counselors.

After 2 years

- 70.7% of patients with diabetes (90% of those who attended for >3 months) and 87.7% of patients on highly active retroviral therapy (HAART) remained in active follow-up

- Median HbA1c was 8.6% (70 mmol/mol), but the degree of improvement could not be assessed in the absence of a baseline measurement

- Median CD4 count doubled in patients on HAART

Continuity, access, coordination and teamwork

These four core principles–continuity of care, access to care, coordination between different levels of care and multidisciplinary team work–really belong together, as they concern providing good quality health care for managing diabetes and preventing its complications. A particular challenge in low resource settings is that of moving away from a focus on episodic curative care. High patient numbers, with acute infectious illness and low numbers of trained professionals have nurtured this approach, which will tend to wait for the patient to present with gangrene of the foot rather than invest energy in identifying the patients at risk. Likewise, there is more focus on treating the problem than empowering the person. For example, a patient with elevated blood glucose levels is more likely to receive a change in prescription than a useful exchange of information about diet or exercise and advice about overcoming barriers to adherence.

Continuity of care

Continuity of care in chronic diseases is a cornerstone of effective health care organization and has been associated with lower mortality, better access to care, less hospitalization and referral, fewer emergencies and better detection of adverse medical events [13,14]. Continuity is easier to achieve when services are offered close to communities where access is easier. Care that requires visits to a distant referral hospital is unlikely to support continuity because of the costs and time taken to travel. In many less well resourced countries and areas, diabetes care has not been part of primary health care offered in the community although there is a clear drive by the WHO to change this.

Central to providing continuity of care is continuity of information, such that the status of individuals is known, in terms of when they attended their last appointment, the next appointment due, and what was found, discussed and prescribed at previous appointments. A diabetes register is therefore essential, providing a list of patients with diabetes being treated at that facility, a record of their appointments, linked to a system to follow-up those who fail to attend for an appointment. In higher income situations, electronic diabetes registers are now the norm, and in some situations registers are maintained across more than one level of care, such as primary and secondary care. In low income situations, an adequate register can be kept using “pencil and paper” at the level of the facility at which most diabetes care is delivered. In addition to keeping a register of patients and their appointments, there is the need to provide continuity of relevant information between visits. In high-resource settings, electronic records linked between different levels of care provide a state of the art approach. In low-resource settings, a range of approaches have been tried (e.g. color coding of patient records, the use of annual summary sheets and patient-retained records) [15]. A simple but effective approach in some settings can be a combined “paper and pencil” register and record, recording a small number of core items such as blood pressure, a measure of blood glucose control, whether feet were examined, advice given and current medication.

Continuity of management aims to provide continuity with a specific group of health care providers. The challenge here is to maintain the same team of people for a reasonable period of time. Relational continuity with the same health care provider over time is occasionally possible and would be an ideal [16].

Access to all

Access to care, of any type at all, is still an issue in many low and middle income countries, particularly in more remote areas. A specific example is the lack of availability or access to insulin leading to unnecessary mortality in people with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) [17,18]. Even when available, the cost of purchasing insulin is substantial and can be the equivalent of up to 20 days wages for a 1-month supply of insulin. Thus, addressing the supply chain for medication and ensuring that essential medication is either free or highly affordable is a prerequisite for improving outcomes, but that is not all that is required. Availability of tests for the diagnosis of diabetes, monitoring of control and equipment to screen for complications are also essential.

A shortage of human resources is a serious barrier to providing access to care in many low and middle income countries, the irony being that these countries are often recruiting grounds for high income countries seeking to staff their own health care systems. Given their shortage, health workers in low resource settings often develop a broader scope of practice than their equivalents in high resource settings and as a result need to have a wide range of skills. This is often necessitated by the absence of more highly trained professionals, particularly in rural and remote areas. Although a less qualified professional may offer lower quality care, there is also the potential for effective substitution, with the right training and organization. This has been well demonstrated by Gill et al. [19] in rural Africa. Using a wholly primary care level nurse-led program, with key elements of education and drug titration by clinical algorithm and using drugs on the essential drug list, significant improvements in glycemic control were noted and maintained over an 18-month period (HbA1c 11.6 ± 4.5%, 103 ± 49 mmol/mol [SD] at baseline, and 7.7 ± 2.0%, 61 ± 22 mmol/mol at 18 months). The impact of education alone was remarkable, as without any change in drug therapy the HbA1c dropped from 10.6 ± 4.2% (92 ± 46 mmol/mol) baseline to 7.6 ± 2.3% (60 ± 25 mmol/mol) at 18 months.

In primary care, well-trained nurses can offer equivalent care to doctors for routine follow-up of chronic conditions, minor illness and preventative interventions [20]. In diabetes, this may mean the nurse conducting the consultation and reviewing results such as urinalysis, HbA1c, glucose and cholesterol levels. The nurse may also screen the feet, take blood pressure and calculate the body mass index. Nurses will then refer to the generalist doctor for complicated or uncontrolled patients. Patient satisfaction may even be higher as consultations are longer and contain more information. Nurses, however, may not necessarily be cheaper as they are less productive [20]. Similarly, in low resource settings the generalist doctor may need a broader range of procedural and surgical skills at the district hospital and the ability to act as a supportive consultant to nurses. A range of mid-level workers such as health promoters and clinical associates/assistants may also provide effective substitution [21].

Management of diabetes and other chronic diseases involves providing access to screening and early intervention to prevent or at least limit the impact of complications [2]. In low resource settings, some complications are easy to screen for (e.g. using a testing strip dipstick to assess for proteinuria or identifying the at-risk foot with a monofilament) provided the necessary tools are available; however, screening for retinopathy is problematic as health providers seldom succeed in overcoming the many obstacles to effective ophthalmoscopy. Nevertheless, even in low resource settings, appropriate technology using a fundal camera may be possible [22,23].

Further decisions need to be made regarding the relative costs and benefits in different resource settings of macro vs micro albuminuria screening; use (and frequency) of glycated hemoglobin vs random/fasting blood glucose as well as total cholesterol vs high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol measurements. Effective screening requires a structured and systematic approach by the health care team.

Coordination of care

Coordination of care from primary to secondary and tertiary levels is needed to provide the full range of diabetes care, if resources allow. In well financed and organized systems, this coordination includes well-developed referral pathways within health districts and regions, and well-developed systems of information exchange between the levels, in order to preserve continuity of care. Specialist services likely to be available at a secondary level include the treatment of foot ulcers, retinal laser therapy, and the investigation and medical treatment of renal impairment. Renal dialysis and replacement is an example of services often provided at the tertiary level. In low and middle income settings, and even in some high income countries where universal health insurance does not exist, access to secondary and tertiary care tends to be highly dependent on the ability to pay.

Teamwork

Teamwork is an essential feature of providing diabetes care. Even at primary health care level, particularly in high income situations, several professionals and disciplines can be involved in the routine care people with diabetes – including, for example, doctor, nurse, podiatrist and optometrist. In order to develop chronic care, the people involved in managing chronic conditions need to develop a team that meets regularly to focus on improving the quality of care [2], and one of the team should be appointed as the chronic care coordinator. If no one is responsible for chronic care, the tendency is for it to be overlooked. For example, basic equipment, such as glucometers, monofilaments or obese cuffs for blood pressure measurement, is not provided [15]. In addition, new ideas, initiatives and procedures are not sustained in the absence of a leader who is present over a sufficient time period. Continuously rotating staff, such as nurses, erodes the ability to create effective teams and sustain changes. When teams meet they should develop shared goals, clarify their complementary roles, reflect on how to improve care and hold each other accountable for decisions. Health professionals need to be clearly aligned with the purpose of improving chronic care and not with defending professional identities. A respectful, open and curious stance helps professionals and others to understand each other better [24].

When nurses working in a large informal settlement in Cape Town were asked what would help improve diabetes care they replied “caring for the carers,” reminding us that building good teams begins by caring for its members. The nature of the relationship between health workers and managers, and the values embedded in the organizational culture may be reflected in the nature of the relationship between health worker and patient and the culture of caring [25]. Organizations that operate too heavily in a mechanistic and bureaucratic model tend to treat health workers as human resources that can be used and replaced like parts in a machine [26]. Organizations should strive for congruence between individual values and behavior and organizational culture and structures [27]. It is difficult for health workers to empower people for healthy living, motivate change and care for patients when the organization is not congruent with the same values. Wheatley [28] expresses this well when she says, “After years of being bossed around, of being told they’re inferior, of power plays that destroy lives, most people are exhausted, cynical and focused only on self-protection … when obedience and compliance are the primary values, then creativity, commitment and generosity are destroyed.” Living health systems should care for, empower and nurture their staff so that they are enabled to do the same for their patients.

Patient-centered care

In low resource settings the need to be patient-centered is often dismissed as a luxury in the face of high workloads and sometimes broad differences in education, language and culture between health providers and patients. Nevertheless, patient-centeredness has been found to improve quality of life, increase patient satisfaction, improve adherence to treatment, enhance the integration of preventive and promotive care, and improve the provider’s job satisfaction. It does not necessarily imply a longer consultation. Patient-centeredness implies a more collaborative approach and holistic understanding of the patient that elicits, acknowledges and addresses relevant beliefs, concerns, ideas and fears [14].

Patient-centeredness is in part a paradigm shift in the mind of the health worker from a bio-medical, technical and sometimes authoritarian model to a biopsychosocial, holistic and participatory model [14]. It is fundamentally a way of being with the patient. Nevertheless, a range of specific communication skills can be learnt such as the ability to ask open as well as closed questions, to make reflective listening statements, exchange information or invite mutual decision-making [29]. While training of doctors has begun to include these communication skills, even in low resource settings, the training of nurses and mid-level health workers often has not.

Motivational interviewing builds on a patient-centered approach and can best be described as a guiding style. Diabetes, which involves multiple changes in behavior (diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol, medication), particularly lends itself to adaptations of motivational interviewing. A challenge in low resource settings is to see how a range of health workers can incorporate a guiding style into their consultations.

In a model of care that emphasizes patient empowerment and self-care as key components [2]. every consultation needs to be seen as an opportunity for this. Health providers need to have the necessary expertise in the relevant topics, useful communication skills and a range of educational materials appropriate to the literacy level of the community. In some settings, group as well as individual approaches may be effective [30].

A family and community orientation

Beyond the individual patient is their family and community context. Clearly, family beliefs and customs and degree of social support will have an impact on the ability of an individual within that family to make lifestyle changes and cope with their diabetes. Involving family members in the consultation or educational program can strengthen the overall response to diabetes [31]. Likewise, an understanding of the patient’s environment will inform discussions about appropriate changes and likely constraints.

In low resource settings, where facilities are overwhelmed with large numbers of patients it may make sense to extend care into the community [2]. For example community-based support groups can be run by health promoters or local non-government organizations to offer some aspects of routine chronic care. Patients can then return to the local clinic for periodic or annual review and help with complications. Support groups can also encourage lifestyle change and adherence to medication. Expert patients, an increasingly developed resource in both low and high income situations, may also be useful to enhance self-care, although further evaluation is required [32]. Community health workers have the potential to promote healthy lifestyle, provide home-based care and link selected patients with the local facilities [33].

Communities should not just be seen as additional platforms for care or targets for interventions but representative structures or key leaders should be engaged with in order to understand how local health priorities are perceived and to elicit feedback and involvement in the planning and delivery of services [14].

Primary care workers usually have a responsibility not just for individual patients but for people living within specific communities or health districts [14]. Concern for the growing number of people with diabetes should lead to interventions that address the underlying determinants of obesity and reduced physical activity: for example, school-based healthy lifestyle programs, provision of green spaces in inner cities, marketing of food to children, sale of junk food on public premises and labeling of food. Many of these require health workers to contribute to interventions in other sectors [34].

Making use of evidence

The evidence base for diabetes is constantly expanding and all the above areas need to be informed by the latest evidence base that is relevant to the resource setting in which it is to be applied. Ideally, a systematic process for reviewing the evidence and updating guidance accordingly should be in place in all countries. An example of such a system from a high income setting is the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the UK. This may be beyond the resources of lower income countries but through regional cooperation, such as coordinated by WHO, the IDF and the World Bank, regular reviews of the evidence appropriate to different resource settings do take place. The availability of evidence does not guarantee that it will be used, and there is a strong and growing literature on how to build local ownership and influence local practice, such as through the development of local treatment guidelines.

Information technology – how to embrace it?

Information technology (IT) is a rapidly growing field that has the capacity to strengthen the model of care for diabetes across different resource settings. The potential targets for IT range from people with diabetes to people at risk for diabetes, health workers and managers. Some of the ways in which IT can strengthen the model for diabetes care are improving continuity of information, assisting in running referral systems between different levels of care, and providing tools for education and empowerment.

Numerous IT modalities or systems exist, although these need to be tailored according to the target population and desired outcome. Thus, real-time imaging and audio contact via equipment such as digital cameras, video phones and computers can permit interaction between health workers and individual patients or groups of patients for education sessions. Dietary management and medication adherence support may be provided by mobile phone messaging; self-care may be enabled by technology-mediated feedback on blood glucose levels on a daily basis. Quality of care may be enhanced by access to the latest evidence or decision-support tools; auditing may be supported by software that automates the analysis of raw data and integrates it with district health information systems.

Innovative strategies for clinical management, especially those which address monitoring of patients by technology-mediated communication with the diabetes care team, are being introduced in high resource settings. One of the key issues to be addressed is the cost-effectiveness of such IT-based systems [35] and the amount that an individual is willing to pay may well depend on their perception of risk. Furthermore, even in high resource settings, a patient’s age and educational background may place limits on their ability to utilize IT [36]. In contrast, at present IT has limited applicability in low resource settings as these are characterized by no or very limited access to the Internet and a lack of familiarity with computers amongst health care workers. Even when a large health center or hospital has computers and Internet access, these are likely to be available to the managers or possibly large clinical areas, certainly not in individual consulting rooms, while such access in primary care settings is simply not to be had for the most part. Furthermore, patients coming from poor backgrounds are very unlikely to have access to the Internet.

Mobile phone-based telecommunication system to enhance patient self-care

Mobile phones, of all the currently available technologies directed at the patient, are likely to have the greatest potential use in low resource settings. This is because the digital divide along the socioeconomic gradient appears to be less evident with mobile phones than other forms of IT, such as the Internet [37,38]. Mobile phones are even to be found in remote villages, indicating the extent of their penetration in contrast to the lack of access to land lines in many rural areas; however, unlike the situation in well-resourced countries where the majority of mobile phone owners have a contract for a year or so, the usual practice in low income countries is one using prepaid phone cards and sharing of phones. If the IT involvement is simply related to the patient’s receipt of messages to support their care, this may not have a negative impact, since even when phone use exceeds the amount paid, the phone may still receive messages, but may not be able to send outgoing comunications.

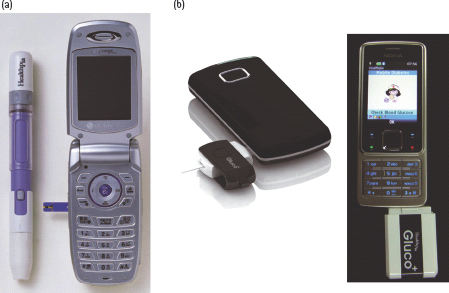

In countries with better resources, mobile phones have been put to additional uses in diabetes care. A real-time telemedicine transmission system has been developed and tested. One system uses a blood glucose monitor connected to a general packet radio system mobile phone to enable transmission of patients’ blood glucose levels [39] with subsequent feedback. Farmer et al. [40] demonstrated that real-time telemedicine was feasible and realistic in a randomized controlled trial. Further, the idea of measuring the blood glucose level directly from the mobile phone has also been introduced (Figure 58.2). Cho et al. [41] reported that the effect of the mobile communication system using the “diabetes phone” (Figure 58.3b) was not inferior to that of an Internet based glucose monitoring systems in terms of supervision, care and patient’s satisfaction. The fact that text messaging on mobile phones is very limited represents a possible disadvantage for utilizing real-time telemedicine in providing information regarding blood glucose status. It is probable that the integration of medical equipment and mobile phones will be developed within the not-too-distant future.

Figure 58.2 Glucometer with telecommunication. Adapted from Cho et al. [41]. (a) The Diabetes Phone (Healthpia, Korea) has a glucometer in a battery pack (phone embedded type). (b) The glucometer can be directly connected to a cellular phone (Dongle type). (Gluco plus, Healthpia, Korea.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree