Miscellaneous Nontumors and Tumors

NONTUMORS

Amyloidosis

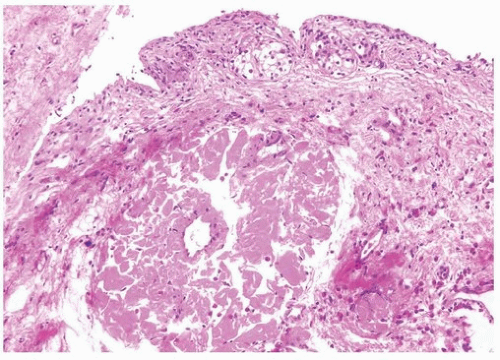

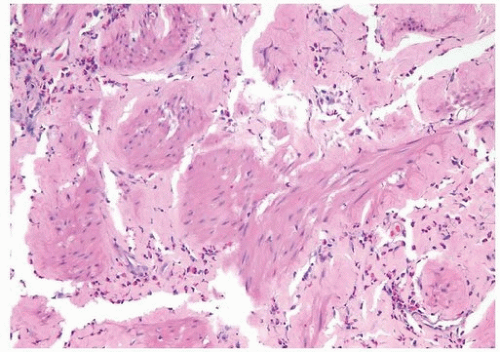

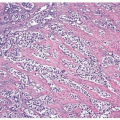

The bladder may be involved in cases of systemic amyloidosis but rarely is the primary site of this disease (1). The usual clinical presentation is that of hematuria. On cystoscopy, a localized amyloid tumor will be seen as an elevated mass that can be confused with an invasive neoplasm. Less frequently, the disease may diffusely involve the bladder wall. Microscopically, the amyloid protein is an eosinophilic, afibrillar material deposited preferentially in the lamina propria and extending into the connective tissue surrounding muscle fascicles (2) (Figs. 12.1, 12.2) (efigs 12.1-12.7). Less frequently, and usually in systemic amyloidosis, there are perivascular amyloid deposits. Congestion and hemorrhage are common, but inflammatory cells are scanty unless the overlying epithelium is ulcerated. A few fibroblast-like cells are usually interspersed within the eosinophilic material. An unusual association of bladder amyloidosis with urothelial carcinoma has been by one of us in half the cases of bladder amyloidosis seen in our practice (unpublished data). Special stains such as Congo red, crystal violet, or van Gieson will help establish the diagnosis. In a minority of cases, there may be a diffuse plasma cell infiltrate. In these cases, studies should be performed for light chain restriction to rule out associated plasma cell dyscrasia. Patients with localized lesions are usually successfully managed by transurethral resection (TUR), but patients with more diffuse involvement may require more radical surgery to control the bleeding (3).

Diverticular Disease

Bladder diverticula are relatively common yet their etiology remains controversial. Most investigators agree that they occur secondary to increased intravesical pressure as a result of obstruction distal to the diverticulum (4, 5, 6, 7, 8). The obstruction brings about compensatory muscle hypertrophy and eventual mucosal herniation in areas of weakness. Others feel that at least some diverticula are a consequence of congenital defects in the bladder musculature, and they cite as evidence cases of diverticula in young

patients with or without evidence of obstruction (9, 10). In the pediatric population, a significant number of cases are associated with other congenital defects, but this association has not been seen in adults. In addition, tumors associated with diverticula rarely occur in children (11). The most common sites of diverticula are adjacent to the ureteral orifices, the bladder dome (probably related to a urachal remnant), and the region of the internal urethral orifice. Grossly one sees distortion of the external surface of the bladder. The diverticula may be widely patent but usually have a narrow os in symptomatic patients. The mucosa adjoining the diverticulum is usually hyperemic or ulcerated. At this site, the urothelium as well as the underlying bladder wall may exhibit reactive changes. Very commonly, there is inflammation involving the lamina propria and muscularis

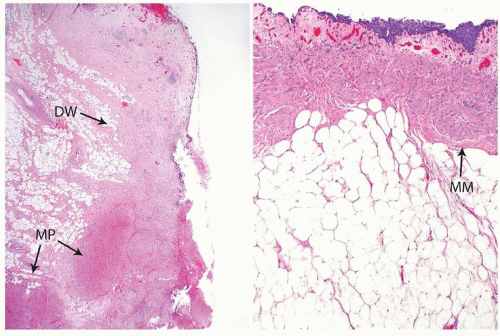

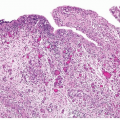

in the area of the diverticular os. The wall of the diverticulum itself consists of urothelium and underlying connective tissue, similar to the bladder mucosa with lamina propria. Fascicles of smooth muscle will be identified in the majority of cases of acquired diverticula but, when present, represent muscularis mucosae, which are hyperplastic. In fact, in some cases, these hyperplastic muscularis mucosae may appear as a relatively thick, continuous layer of smooth muscle. By definition, bladder diverticula in adults do not contain muscularis propria, an important fact that influences pathological staging of tumors (Fig. 12.3). The true “congenital” diverticula seen in the pediatric age group contain a thinned outer muscle layer. The urothelium lining the sac may undergo squamous or glandular metaplasia due to local irritation associated with urine stasis, irritation, or stone. In these cases, it is not unusual for the diverticular wall to become extensively fibrotic.

patients with or without evidence of obstruction (9, 10). In the pediatric population, a significant number of cases are associated with other congenital defects, but this association has not been seen in adults. In addition, tumors associated with diverticula rarely occur in children (11). The most common sites of diverticula are adjacent to the ureteral orifices, the bladder dome (probably related to a urachal remnant), and the region of the internal urethral orifice. Grossly one sees distortion of the external surface of the bladder. The diverticula may be widely patent but usually have a narrow os in symptomatic patients. The mucosa adjoining the diverticulum is usually hyperemic or ulcerated. At this site, the urothelium as well as the underlying bladder wall may exhibit reactive changes. Very commonly, there is inflammation involving the lamina propria and muscularis

in the area of the diverticular os. The wall of the diverticulum itself consists of urothelium and underlying connective tissue, similar to the bladder mucosa with lamina propria. Fascicles of smooth muscle will be identified in the majority of cases of acquired diverticula but, when present, represent muscularis mucosae, which are hyperplastic. In fact, in some cases, these hyperplastic muscularis mucosae may appear as a relatively thick, continuous layer of smooth muscle. By definition, bladder diverticula in adults do not contain muscularis propria, an important fact that influences pathological staging of tumors (Fig. 12.3). The true “congenital” diverticula seen in the pediatric age group contain a thinned outer muscle layer. The urothelium lining the sac may undergo squamous or glandular metaplasia due to local irritation associated with urine stasis, irritation, or stone. In these cases, it is not unusual for the diverticular wall to become extensively fibrotic.

Major complications of bladder diverticula include infection, lithiasis with subsequent obstruction, and carcinoma (12, 13, 14). It is believed that 2% to 7% of patients with bladder diverticula will develop an associated urothelial neoplasm, presumed secondary to the chronic inflammatory stimuli mentioned above. The neoplasms may develop at the orifice or may occur within the diverticula, making endoscopic evaluation difficult. While “usual” urothelial carcinomas predominate, there is a relative increase in urothelial tumors with divergent differentiation in the form of squamous carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, at times associated with squamous or glandular metaplasia

in the lining urothelium. Rare cases of small cell carcinoma have been described. Sarcomas also have been reported in association with bladder diverticula, but we feel that most, if not all, of these cases are likely to represent sarcomatoid transformation in high-grade urothelial carcinomas (14). Survival is dependent on completeness of excision (negative margins) and stage at the time of resection with tumors invading the lamina propria (pT1) having a better disease-specific survival than tumors that extend into the peridiverticular soft tissue (pT3) (15, 16).

in the lining urothelium. Rare cases of small cell carcinoma have been described. Sarcomas also have been reported in association with bladder diverticula, but we feel that most, if not all, of these cases are likely to represent sarcomatoid transformation in high-grade urothelial carcinomas (14). Survival is dependent on completeness of excision (negative margins) and stage at the time of resection with tumors invading the lamina propria (pT1) having a better disease-specific survival than tumors that extend into the peridiverticular soft tissue (pT3) (15, 16).

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue

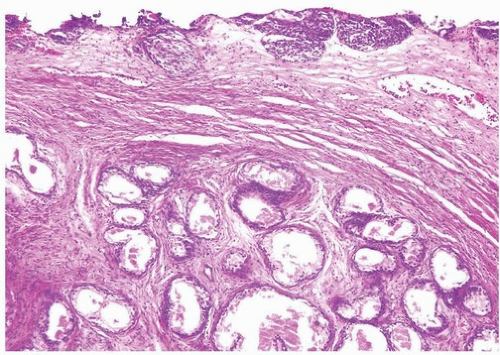

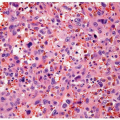

Ectopic prostatic polyps within the bladder are usually single, polypoid lesions usually around the trigone (17). These lesions typically present with gross and microscopic hematuria. The lesions may occur over a wide age range but are more frequently detected in young men. Histologically, the submucosal component of the urethral polyps is composed of stroma and prostatic glands (Fig. 12.4). The glands may be closely packed, and in some areas, they may be cystically dilated at the periphery. The surface of urethral polyps is often papillary with broad papillae lined by urothelial cells, prostatic epithelial cells, or a combination of both. Rarely, these polyps have broad finger-like villous projections lined by benign prostatic epithelium. The presence of corpora amylacea and double layered is a helpful clue to the prostatic origin of the lesions, and rarely prostate-specific immunohistochemistry may be required to rule out other benign mimics including cystitis glandularis. These lesions are totally benign.

Fibroepithelial Polyp

Fibroepithelial polyp of the lower urinary tract is a relatively rare disease entity that is considered to be a nonneoplastic condition, some arising from acquired conditions and others congenitally (18). It has a marked

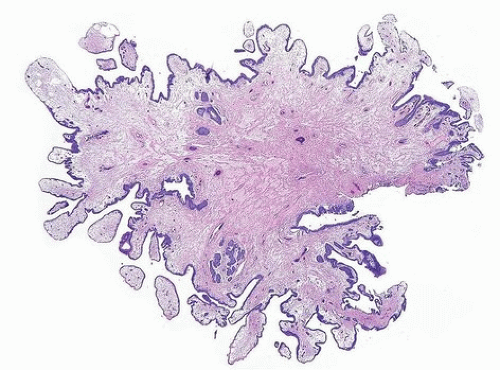

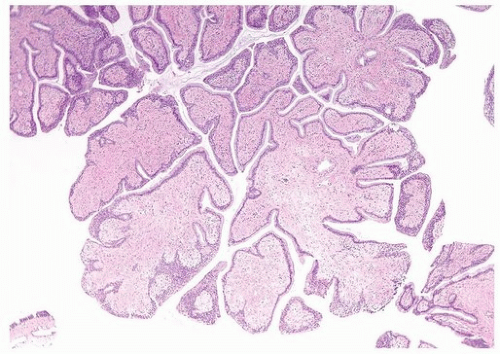

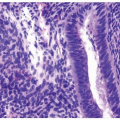

male predominance. More than half of the reported cases occur in neonates or children, some of which are associated with urogenital malformations. However, cases have also been reported from the second to fourth decades. Their main clinical manifestations are urinary obstruction, urinary hesitancy, dysuria, enuresis, hematuria, infection, and flank pain. They are usually diagnosed by cystourethrography or cystoscopy and are treated by TUR, following which the lesion does not usually recur. Most cases are located near the verumontanum or the bladder neck. Histologically, fibroepithelial polyps are predominantly composed of urothelial epithelium and fibrovascular stroma showing a finger-like or polypoid growth pattern (Figs. 12.5, 12.6, 12.7) (efigs 12.8-12.11). Urothelium shows tubular or anastomosing structures with colloid-like secretions in some cases, resembling

cystitis cystica. Although some of the urothelium shows focal squamous or mucinous metaplasia or becomes thin or denuded, none contain significant cytological atypia. The stroma of the polyps typically contains relatively frequent small vessels, some of which are dilated or congested. Stromal edema, either focal or extensive, is also a common finding. Although the stromal cells can show atypia with multinucleated cells and hyperchromasia, the atypia appears degenerative in nature, lacking prominent nucleoli and mitoses.

male predominance. More than half of the reported cases occur in neonates or children, some of which are associated with urogenital malformations. However, cases have also been reported from the second to fourth decades. Their main clinical manifestations are urinary obstruction, urinary hesitancy, dysuria, enuresis, hematuria, infection, and flank pain. They are usually diagnosed by cystourethrography or cystoscopy and are treated by TUR, following which the lesion does not usually recur. Most cases are located near the verumontanum or the bladder neck. Histologically, fibroepithelial polyps are predominantly composed of urothelial epithelium and fibrovascular stroma showing a finger-like or polypoid growth pattern (Figs. 12.5, 12.6, 12.7) (efigs 12.8-12.11). Urothelium shows tubular or anastomosing structures with colloid-like secretions in some cases, resembling

cystitis cystica. Although some of the urothelium shows focal squamous or mucinous metaplasia or becomes thin or denuded, none contain significant cytological atypia. The stroma of the polyps typically contains relatively frequent small vessels, some of which are dilated or congested. Stromal edema, either focal or extensive, is also a common finding. Although the stromal cells can show atypia with multinucleated cells and hyperchromasia, the atypia appears degenerative in nature, lacking prominent nucleoli and mitoses.

Urothelial papilloma may be difficult to differentiate because both lesions show a polypoid or finger-like growth pattern and lack of cytological atypia of the urothelium. However, urothelial papilloma usually has thin fibrovascular cores in contrast to the relatively broad stroma of fibroepithelial polyp. Rarely, exstrophy of the bladder may present as a polyp (19, 20). While the age and the clinical setting are typical, deep penetrating nests of urothelium or metaplastic glandular epithelium with or without cystic change may result in diagnostic difficulty with a neoplasm. A unique cuff of periepithelial fibrosis also helps in the correct diagnosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree