Abstract

Breast lymphoma and mesenchymal neoplasms of the breast are rare entities. The large continuum of disease includes fibroepithelial, vascular, lipomatous, neural, myogenic, and osseous neoplasms. In this chapter, we explore these diseases in depth, in addition to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the most common breast lymphoma.

Keywords

breast, mesenchymal, neoplasm, lymphoma, rare

Mesenchymal tumors and primary lymphomas of the breast are rare but distinct entities. Primary breast sarcoma and the fibroepithelial neoplasms, such as fibroadenoma and phyllodes tumor, both arise from mesoderm, the connective tissue of the breast. The first section also describes the more uncommon fibroblastic and myofibroblastic tumors, vascular neoplasms, and lipomatous and neural tumors of the breast and concludes with the myogenic and rare osseous neoplasms that can arise from breast mesenchyme. The second part of the chapter is devoted to discussion of primary breast lymphomas, with a focus on the more prevalent diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Mesenchymal Neoplasms of the Breast

Breast Sarcoma

Primary breast sarcoma accounts for less than 1% of all breast malignancies and less than 5% of all soft tissue sarcomas. Estimated annual incidence is 4.6 new cases per million women. Primary breast sarcoma has no known etiology; however, radiation and chronic lymphedema may be associated with secondary breast sarcoma. A 90-year review of the Mayo Clinic database revealed that primary breast sarcoma accounted for 0.06% of all breast cancers. Angiosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, and unclassified sarcoma are the most frequent subtypes. Breast sarcoma rarely involves local lymph nodes due to hematogenous spread. Incidence of lymphatic spread is less than 5%, and outcomes are not improved with lymph node dissection. In the absence of palpable axillary lymphadenopathy, routine lymph node dissection should not be undertaken. If axillary lymph node metastasis has been pathologically documented, then lymph node dissection is indicated. With few exceptions, sarcomas require total mastectomy. The most important prognostic factor is negative surgical margins.

Fibroepithelial Neoplasms

Fibroadenoma

Fibroadenoma (FA) is a common cause of breast masses that are prone to affect women between 15 and 35 years of age. FA is a painless, mobile lump that is unilateral, bilateral, or infrequently multifocal. The cut surface has a distinctive bulging, firm, off-white nodular look, which is sharply delimited from surrounding breast tissue. Calcification may be present. A homogeneous increase in stromal connective tissue distorts ductal epithelium into long, thin, intersecting compressed strands (intracanalicular pattern) or surrounds ductules in a circumferential manner (pericanalicular pattern). Both patterns may occur in the same mass; neither have biological significance. Stromal nuclei are spindle-shaped and euchromatic with smooth nuclear contours. Ductal epithelium may exhibit a wide range of proliferative and nonproliferative changes. FA is considered a proliferative lesion ; however, most simple FAs do not portend an increased risk of breast cancer. If there is an adjoining proliferative lesion, breast cancer family history, or if the FA is complex, then there may be increased risk of breast cancer. Juvenile FA is a diagnosis reserved for tumors that have a rapid growth rate, are very large (>10 cm), and arise in adolescence. Complex FA contains one or more complex features, such as epithelial calcifications, papillary apocrine metaplasia, sclerosing adenosis, and other proliferative changes. Typically, FA is managed with observation alone and tumors often shrink without intervention. However, if the diagnosis is uncertain or if the tumor causes discomfort, lumpectomy or excisional biopsy may be necessary. Cryoablation is another treatment option in certain cases, if the diagnosis is certain.

Phyllodes Tumor

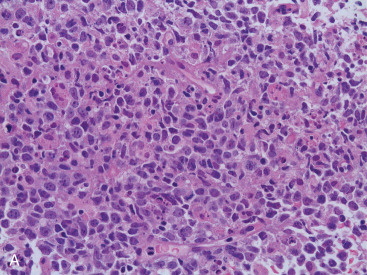

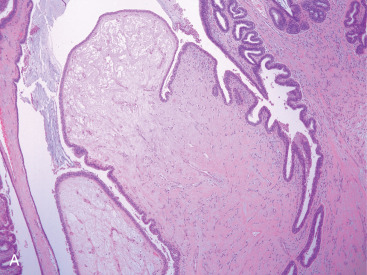

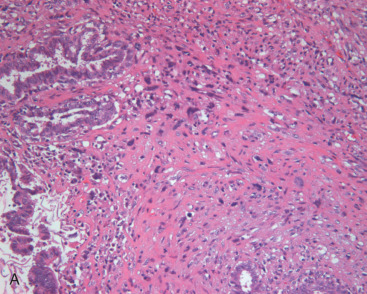

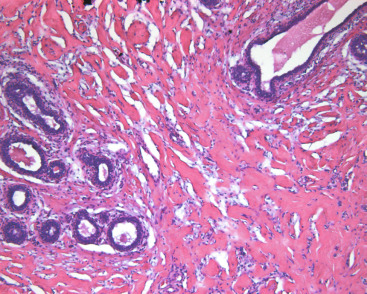

Phyllodes tumor (PT) is an exceptionally rare breast neoplasm representing less than 0.5% of all primary breast tumors. After it was first described, it was not known to have malignant potential for almost 100 years. Mean age at diagnosis is 42 to 45 years of age, although a broad age range exists. Tumor size is variable and axillary lymph nodes are uncommonly involved. Grossly, PT has a whorled pattern with visible cracks or fissures. Cystic change, hemorrhage, and necrosis may occur in large neoplasms. The biphasic nature involves a benign epithelial component and an abnormally cellular stromal/mesenchymal component. Although the stroma is generally more cellular than that seen in FA, a more important distinguishing feature is that stromal cellularity is heterogeneous. Frond-like stromal overgrowth (accounting for the term phyllodes ) produces an exaggerated intracanalicular pattern and is also a more reliable feature of PT ( Fig. 11.1A ). Like FA, benign PT has a circumscribed edge, cytologically uniform stromal cells, and few mitoses ( Fig. 11.1B ).

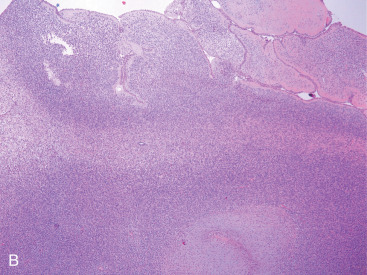

Histologic grading of PT into benign, borderline, and malignant categories is recommended. This classification is based on a constellation of features, including mitotic count, degree of stromal overgrowth (defined as lack of any epithelial component in at least 1 low-power/40× field), and whether the border is infiltrative or circumscribed. Different authors use different mitotic counts to subdivide PT into various grades, ranging from 1 to 2 per 10 high-power fields (HPFs) for benign PT, to up to 10 mitoses per 10 HPFs for borderline PT ( Fig. 11.2 ). The World Health Organization avoids a strict numerical count because of the variability of HPFs among microscopes. Instead, a semiquantitative method of few if any mitoses, intermediate number of mitoses, and numerous mitoses (>10 mitoses per 10 HPFs) is used to help subclassify PT into benign, borderline, and malignant categories, respectively. Classification criteria also include degree of stromal cellularity and atypia, presence or absence of infiltrative margins, and stromal overgrowth. Along with stromal heterogeneity, hyalinization and myxoid change are common. Benign heterologous elements, including chondroid, osseous, squamous, and lipomatous metaplasia, may be seen in benign PT, whereas malignant PT may contain foci of liposarcoma, undifferentiated/unclassified sarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Distinction between benign PT and FA is imprecise, and it is particularly problematic with core needle biopsy specimens. Lee and colleagues found that higher stromal cellularity (compared with FA in >50% of the cores), stromal overgrowth, fragmentation (defined as stromal fragments with epithelium at one or both ends), and adipose tissue within stroma are statistically significant features useful in separating PT from FA in needle biopsies.

Malignant PT is recognizable by its cellular pleomorphism, stromal overgrowth, atypical heterologous elements, and mitotic count ( Fig. 11.3A ). Ki-67 staining has been used as a proliferation marker but adds little to mitosis counting. Size alone is not a predictor of malignancy. Overexpression of p53 and the epidermal growth factor receptor gene are not correlated with outcome. Estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) expression positivity may be seen in the epithelial component but are rare in the stroma.

Resection of PT with negative histologic margins is recommended. Recurrence correlates primarily with completeness of resection; however, recurrence is not certain even with positive margins. Locally recurrent tumors are usually the same grade as the original. Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) within PT correlates with a decreased risk of recurrence in one study. Lymph node metastasis is rare, and hence axillary lymph node dissection is not routinely performed. Metastases occur in less than 10% of cases and consist of sarcomatous stroma. Lung, pleura, and bone are the most common metastatic sites (see Fig. 11.3B ).

Adjuvant chemotherapy does not appear to affect survival in PT. However, some advocate for chemotherapy in tumors greater than 5 cm or recurrent malignant tumors. The use of radiation therapy remains controversial. Some advocate for radiation therapy in the setting of borderline and malignant PTs because it is associated with decreased recurrence. There is no role for endocrine therapy in PT, given the ER negativity of the stromal area.

Mammary Hamartoma

Hamartoma is a well-delimited mass that occurs in perimenopausal women as an incidental mammographic finding. It is composed of benign breast lobules, adipose tissue, and fibrous tissue in varying quantity, without the lobular structure of FA, and is outlined by a pseudocapsule of compressed breast tissue. Surgical excision is indicated due to the possibility of coexisting malignancy.

Fibroblastic and Myofibroblastic Neoplasms

Fibromatosis

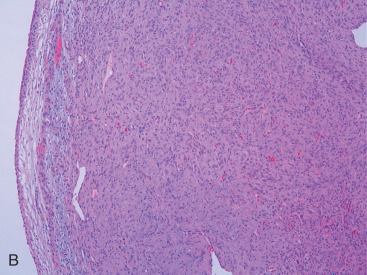

Fibromatosis is a proliferation of fibroblasts that comprises less than 0.2% of breast lesions. Women of a wide age range (15–80 years of age; median, 40 years) are affected. A unilateral painless, firm mass that is mammographically indistinguishable from carcinoma is typical. Grossly, this is a firm, off-white lesion averaging 2 to 3 cm that deceptively appears to be circumscribed; some cases show irregular stellate borders. Even with circumscribed lesions, radially oriented extensions of tumor subtly infiltrate adjacent tissue, making it difficult to judge adequacy of resection. Light microscopy reveals banal-appearing fibroblasts with oval to spindle-shaped pale nuclei arranged in interlacing fascicles set in a variably dense collagenous matrix ( Fig. 11.4 ). Lymphocyte clusters are common. Fibromatoses are vimentin and β-catenin (80%) positive, and they are cytokeratin, ER, and PR negative. Although these tumors are benign, they can be locally aggressive and locally recurrent. Complete surgical excision with negative margins remains standard treatment.

Myofibroblastoma

Mammary-type myofibroblastoma (MYB) is an uncommon neoplasm that affects men almost as much as women. A unilateral circumscribed mass occurs in patients in their fourth to eighth decades. MYB is a benign, slow growing, stromal tumor. It ranges from 1 to 10 cm in size, although most are 4 cm or less at presentation, and has a homogeneous bulging pink cut surface. Multilobulation and myxoid foci may be seen. There is a broad morphologic spectrum, but typically, features of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are present. Microscopically, MYB is characterized by a spindle cell proliferation with few mitoses set in a fibrous stroma. Collagen bundles are typically thick and ropy, with cells laid down in short, randomly intersecting fascicles, rather than the long, sweeping fascicles seen in fibromatosis ( Fig. 11.5 ). Cells have small oval/elongated nuclei, small nucleoli, and occasional grooves. Mitoses are rare, but mast cells are usually numerous. Morphologic variations include an infiltrative rather than circumscribed border; myxoid change; multinucleated giant cells; and cartilaginous, osseous, or fatty metaplasia (so-called lipomatous MYB). Immunohistochemically, most of these tumors are positive for vimentin, α-smooth muscle actin, bcl-12, and CD99; variable expression can be seen in different tumor areas. Immunohistochemical (ICH) stains for cytokeratin, EMA, S100, HMB-45, and c-kit are consistently negative. There is variable positive staining for ER and PR. Surgical resection is recommended. If margins are negative, recurrence is unlikely.

Hemangiopericytoma

So-called hemangiopericytoma is an older term used to describe a benign spindle cell neoplasm with a branching vascular pattern, which is its most conspicuous feature. This tumor originates from capillary pericytes. Proliferating plump oval- to spindle-shaped cells focally entrap ducts and ductules at the lesion’s edge. A thin-walled “staghorn”-type branching vascular pattern is seen throughout the tumor. Its occurrence in the breast is rare. Clinical presentation varies, but most often hemangiopericytoma manifests as a slowly enlarging painless mass. Hemangiopericytomas range in size from 1 to 19 cm and exhibit a firm gray-white cut surface. Surgical resection with negative margins is the recommended treatment and is potentially curative.

Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia

PASH is not a true vascular lesion but a peculiar proliferation of cytologically bland stromal fibroblasts/myofibroblasts that creates empty slitlike spaces mimicking a vasoformative lesion. On average, patients are diagnosed in the fourth decade of life, but a wide continuum exists. The clinical spectrum of PASH ranges from an incidental microscopic finding (most common), to a palpable/nodular mass (rare), to breast thickening, to diffuse breast involvement. Nodular forms of PASH resemble FA or mammary hamartoma on imaging and gross pathology examination. Tissue spaces formed by separation of densely hyalinized collagen fibers may or may not be lined by cells ( Fig. 11.6 ). This proliferation may create a concentric perilobular pattern. Fibroblasts lack cytologic atypia or mitoses, and necrosis and effacement of normal breast tissue are absent. Gynecomastia-like changes include apocrine metaplasia, ductal hyperplasia, and cystic change. Cells show positive staining for CD34, muscle-specific actin, calponin, and the PR ; CD31 and cytokeratin stains are negative. Surgical resection is required only if the lesion enlarges. Other considerations for resection include Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System 4 or 5 lesions on mammography, discordance, or clinically symptomatic lesions.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor

Primary breast inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) represent a relatively rare benign mesenchymal disorder and are scarcely reported in the literature. They are generally considered a subtype of inflammatory pseudotumors, and the World Health Organization classifies them as borderline lesions that can variably range from reactive to truly neoplastic. IMTs have been observed to occur in any anatomic region and tend to affect younger individuals. Most lesions are solitary, mobile, slow-growing masses that may or may not be seen on a mammogram; their appearance on ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not particularly differentiating, and tissue biopsy is needed for diagnosis. Microscopically, they are characterized by spindle cell proliferation and predominantly lymphocytic or plasmacytic inflammatory infiltrates. Although IMTs were initially thought to develop triggered by inflammatory or infectious stimuli, the pathogenesis is now known to involve cytogenetic aberrations in chromosomes 2 and 9. In addition, nearly half of breast IMTs also have clonal abnormalities in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene at 2p23, which favors a neoplastic process. The clinical and prognostic significance of ALK-positivity remain unclear, however. Immunohistochemistry is also important in obtaining the correct diagnosis of IMT because the spindle cells typically express CD34 and desmin but are negative for cytokeratins or S100.

Treatment of IMT of the breast is wide local excision with negative margins. Axillary involvement appears rare, and thus routine sentinel lymph node biopsy is probably unnecessary. Recurrence rates up to 25% have been reported for IMT at other anatomic sites, but there is a paucity of data on recurrence and metastasis of breast IMT. Chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and antiinflammatory agents have not been consistently effective in the treatment of breast IMT, and thus surgery is the mainstay of management.

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) of the breast is a rare tumor. Approximately 50 cases have been reported. Average size of breast MFH is 6 cm. Mean age at presentation is 57 to 67 years. MFH has been divided into four subtypes: pleomorphic MFH, myxofibrosarcoma, giant cell MFH, and inflammatory MFH. IHC is typically negative for epithelial markers but positive for vimentin. Surgical resection with negative margins is recommended. Axillary lymph node dissection should not be performed if there is a clinically negative axilla. The role of adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy for MFH is unclear.

Vascular Neoplasms

Hemangioma

Vascular neoplasms occur either within the breast parenchyma proper or in the overlying skin/subcutis. Mammary hemangiomas have been described in patients of all ages, ranging from infancy to the elderly. All hemangiomas lack anastomosing connections, endothelial tufting, and atypical mitoses, and they are often an incidental finding. Benign hemangiomas include perilobular, cavernous, and capillary hemangiomas. Of the various subtypes, cavernous hemangioma is most common, consisting of large, widely dilated vessels separated by thin fibrous septa and lined by flattened endothelial cells. These lesions are well circumscribed. Intraluminal thrombi are not uncommon. Capillary hemangiomas consist of numerous small, closely packed vascular channels with a lobular pattern, which often lack luminal red cells. Perilobular hemangiomas comprise a lobular expansion of small- to medium-sized blood-filled vessels within the intralobular stroma. Many examples also extend into extralobular stroma and adipose tissue. Perilobular hemangiomas are not particularly rare, being encountered in 11% of 210 forensic autopsies.

Atypical vascular lesions after radiation therapy are usually restricted to the dermis and, in contrast to angiosarcoma (AS), are well circumscribed and generally less than 1 cm in size. They present as erythematous/bluish papules, nodules, or vesicles. There is a median latency of 3.5 years after radiation therapy. Atypical vascular lesions have a lymphangiomatous quality, with thin-walled, irregular vascular spaces that are empty or filled with proteinaceous material. Focal dissection into dermal collagen is seen. Endothelial cell nuclei are hyperchromatic, with some displaying a hobnail projection into the lumen but lacking the necrosis, mitoses, and dissection into the subcutis that is typical of AS. Their clinical behavior is benign. Some experts have proposed that atypical vascular lesions and cutaneous AS represent a morphologic continuum. Ki-67 ICH may be helpful in distinguishing atypical hemangioma from AS. Hemangiomas of the breast are effectively treated with surgical excision, although if vascularity precludes surgical resection, radiation therapy can be considered. Alternatively, transcatheter embolization is an option for tumors that have infiltrated through surrounding muscle layers and are not amenable to surgical removal.

Angiomatosis

Angiomatosis (diffuse hemangioma) of the breast is a rare benign entity. It affects patients from infancy to the sixth decade but typically occurs in young women. A diffuse network of sinusoidal small and large anastomosing vessels affects a large area of the breast. Vessels proliferate around but not into terminal duct lobular units. In contrast to AS, vessels have a uniform distribution; a heterogeneous appearance of large venous, cavernous, and capillary-type channels; and endothelial cells that lack cytologic atypia or tufting. These lesions do not progress to sarcoma.

Hemangioendothelioma

Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is an exceedingly rare primary breast tumor. Like its soft tissue equivalent, it demonstrates an infiltrative population of epithelioid cells arranged in nests or short cords, with rounded enlarged nuclei and eosinophilic or singly vacuolated cytoplasm. The tumor is set in a chondromyxoid or hyaline matrix. A possible association with breast implants has been reported. Unlike hemangioma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma can be misinterpreted as a carcinoma because of its epithelioid morphology and positive staining with pan-cytokeratin markers in addition to endothelial markers. However, they are also IHC positive for vascular Ag (CD31, 34, fVIII), which are not positive in breast cancers.

Angiosarcoma and Related Syndromes

AS accounts for 3% to 9% of all breast sarcomas and less than 1% of all breast tumors. AS is divided into two categories: primary AS and secondary AS, the latter of which arises after radiation therapy, mastectomy, and/or chronic ipsilateral lymphedema, in which case it is termed Stewart-Treves syndrome.

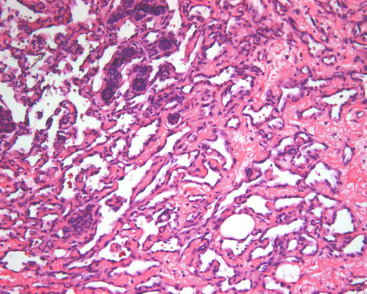

Primary AS typically presents as a fast-growing, painless mass. Tumors range from 2 to 20 cm and average 4 to 5 cm in diameter. Macroscopically, the cut surface varies from hemorrhagic and spongy (low-grade AS) to firm, dull-white, and variably necrotic (high-grade AS). The most widely recognized histologic classification subdivides AS into low, intermediate, and high grades, with 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of 91%, 68%, and 14%, respectively. High-grade (grade III) AS is most common in younger patients and consists of more than 50% solid and spindle cell areas. These foci exhibit pleomorphism, hyperchromatic nuclei, macronucleoli, numerous mitoses, endothelial tufting, and papillary formation. A characteristic of AS is infiltration and destruction of preexisting terminal duct lobular units. CD31 staining is nearly always positive in grade III AS; CD34 and factor VIII–related antigen may be negative. There may also be necrosis. Low-grade (grade I) AS is deceptively bland and may be potentially misdiagnosed as hemangioma. It has widely patent interanastomosing vascular channels that dissect within stroma but are lined by hyperchromatic nuclei with few or no mitoses ( Fig. 11.7 ). Solid foci, papillary formations, and blood lakes are absent. Intermediate-grade tumors have less than 25% solid foci and occasional endothelial tufting, but they lack necrosis. A diagnostic pitfall is the bland, almost hemangioma-like appearance at the periphery of low- and intermediate-grade AS. This is particularly challenging when evaluating a small biopsy or incompletely sampled tumor.

Bone, liver, lung, ovary, skin, and brain are common metastatic sites for AS. Contralateral breast involvement may also occur. Because AS has a predilection for microscopic extension beyond the main mass, wide resection margins are required, thereby necessitating mastectomy in most patients. Lymph node metastasis is rare; hence, axillary lymph node dissection is not typically performed. Prognosis is directly related to the histologic grade of the AS.

Development of AS in the ipsilateral arm after radical mastectomy and axillary dissection, described by Stewart and Treves (S-T syndrome), is secondary to long-standing lymphedema. The incidence of S-T syndrome is 0.1 to 0.5%, and it develops, on average, 10 years after mastectomy. Pulmonary metastases are common, yielding a median survival of 19 months. Increased use of breast conservation surgery and sentinel node biopsy has led to a reduction in this clinical form of AS. Secondary AS after radiation therapy has increased, however, with many cases documented in the literature.

AS occurring after radiation therapy is a cancer of postmenopausal women. On average, affected patients are in their sixth to seventh decades of life. Postradiation AS can arise either in the chest wall after mastectomy, but currently it is more apt to occur in the breast tissue after conservative treatment. Unlike primary AS, it is primarily a dermal/subcutaneous tumor, with patients commonly complaining of cutaneous violaceous or nonpigmented nodules, plaques, vesicles, and macules. The incidence of AS, which is 5 to 9 times higher in patients with breast cancer who receive radiotherapy, is estimated to range from 0.09% to 0.16%. Relative risk ranges from 11 to 15.9, with a latency period of 6 months to 17 years (median 5–6 years) after radiation therapy. Light microscopy reveals an ill-defined infiltrative neoplasm dissecting within dermal collagen and involving subcutaneous fat. Cells lining slitlike spaces show moderate nucleomegaly, hyperchromasia, and distinct nucleoli. Mitotic figures and papillary tufting are common. Similar to primary AS, these may be subdivided into low-, intermediate-, and high-grade sarcoma. Most patients suffer multiple local recurrences; thus, the mainstay of treatment is wide local excision.

However, other treatment modalities have also been effective in treating AS and should also be considered. A single institution experience showed that patients with secondary AS after breast conserving surgery were effectively treated with hyperfractionated accelerated reirradiation (HART), with or without subsequent surgery. Patients received three radiation treatments per day, 5 days per week at 1 Gy per fraction, to total doses of 45 Gy, 60 Gy, and 75 Gy, depending on the risk for subclinical disease or presence of gross disease. HART was well tolerated, and OS, progression-free survival (PFS), and cause-specific survival rates were higher than in patients treated with surgery alone, conventional radiation therapy, or chemotherapy. HART followed by surgical excision and vascularized flap closure can thus be considered in select cases of breast AS arising after breast conserving surgery.

Another novel approach to the treatment of AS includes electrochemotherapy, where chemotherapy such as bleomycin is given intravenously and delivered to tumors via percutaneous electric pulses. This therapy has shown cytotoxic and antivascular effects, and a small study demonstrated that electrochemotherapy can be useful for superficial advanced AS, including of the breast, with improved local PFS as well as palliation of pain and bleeding.

Lipomatous Neoplasms

Lipoma

Intramammary lipomas are uncommon, with most appearing in women in their fourth and fifth decades. These tumors are well demarcated and thinly encapsulated, showing identical morphology to the surrounding mature adipose tissue. Degenerative changes such as focal fat necrosis, calcification, hyalinization, and myxoid change may be seen. Average size is 2 to 3 cm in diameter. Angiolipoma is typically a subcutaneous lesion composed of small capillary-sized vessels within a lipoma. Intraluminal thrombi are commonly seen. Chondrolipoma contains plates of hyaline-type cartilage randomly distributed within a nodule of adipose tissue. Other types of lipoma include spindle cell lipoma, hibernoma, adenohibernoma, and myolipoma. Lipomas have low potential for malignant transformation. Definitive treatment of breast lipomas is surgical excision, although this can pose reconstructive challenges.

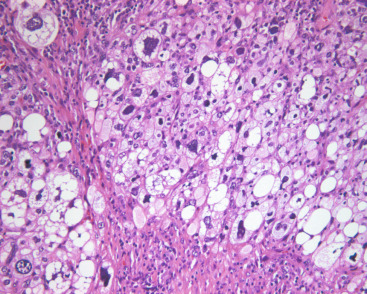

Liposarcoma

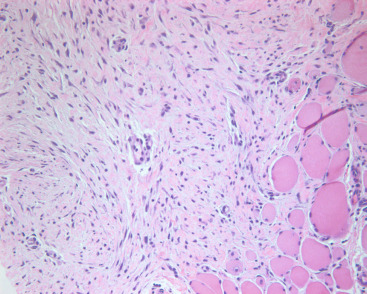

Primary pure liposarcoma of the breast is exceedingly rare. Sufficient tumor sampling is required to exclude an underlying malignant PT with secondary liposarcomatous differentiation. There are no distinguishing clinical features. Patients affected range in age from young adults to elderly individuals, but mean age at presentation is 47 years. Tumors are typically slow growing and sometimes painful. Most are firm, well demarcated, and larger than 5 cm (mean 8 cm). All major histologic subtypes (well differentiated, myxoid/round cell, dedifferentiated, and pleomorphic) have been reported. Like their soft tissue equivalent, mammary liposarcoma shows lipogenic differentiation ( Fig. 11.8 ) and has the potential to locally recur and metastasize. Surgical excision is warranted for localized tumors, and adjuvant radiation therapy may be needed if there are high-risk features such as positive margins. Systemic chemotherapy is necessary for metastatic disease. However, adjuvant chemotherapy and its benefit remain controversial. It should be considered for high-grade breast sarcomas with size greater than 5 cm or lymph node involvement.

Neural Neoplasms

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumor of the breast is an uncommon lesion that arises from primitive nerve cells and frequently affects African American women in the fourth decade of life or earlier. It can be confused with carcinoma both clinically (very firm to palpation, cutaneous retraction) and radiologically (irregular spiculated mass). Less than 5% of lesions are multifocal. Tumor diameter ranges between 2 and 4 cm. The cut surface shows a spiculated scirrhous gray white/yellow lesion. Microscopically, large cells with an enormous amount of coarsely granular cytoplasm infiltrate a densely collagen matrix. Nuclei are slightly enlarged and rarely display any mitoses. S100 and CD 68 staining by IHC is present in nearly all cases. Rare malignant forms are characterized by high cellularity, large nuclei, mitoses, and spindling.

Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis, a benign breast lesion characterized histologically by noncaseating granulomas, small abscesses, and an inflammatory infiltrate, poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges and is often confused with carcinoma. Appropriate imaging followed by core biopsy for culture and pathology is needed for diagnosis. A trial of antibiotics is reasonable during workup. Treatment approaches have included observation only, steroids, wide local excision, and mastectomy, depending on the severity of symptoms. In a small case series of 116 patients, idiopathic granulomatous mastitis was successfully managed with observation (n = 9, 56%), steroids (n = 29, 42%), partial mastectomy (n = 75, 79%), and mastectomy (n = 3, 100%). The authors propose an algorithm for management of this condition based on clinical findings and symptom severity: if the tumor is localized and symptoms are mild, excision, steroids, or observation can be considered; if findings are generalized and symptoms are severe, steroids can be tried, but if unsuccessful, mastectomy should be performed.

Benign Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Neurofibroma.

Neurofibromas are benign subcutaneous tumors comprised of Schwan cells, perineural-like cells, and fibroblasts admixed with nerve fibers, collagen, and myxoid matrix. The majority of lesions are solitary (90%) and not associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Neurofibromas are classified by location and appearance. They occur alongside any peripheral nerve, giving them a fusiform shape, but are commonly found in skin or subcutaneous tissues. They rarely arise in the breast, but when they do, they usually arise in the setting of NF1 and tend to be periareolar. Presentation and size varies, but the NF1-associated lesions are typically larger and are more frequently multiple than the sporadically occurring lesions. Mammography and ultrasound reveal well-defined benign appearing masses. Computed tomography (CT) or MRI can better characterize the lesions; on T2 images, a neurofibroma may have a characteristic hypodense central region, attributed to dense collagen and fibrous tissue in the center of the tumor. Histologic examination reveals spindle cells with thin, often wavy nuclei that stain positive for S100. Treatment of asymptomatic neurofibromas is often not necessary, but local excision can be performed for cosmesis.

Schwannoma.

Also called neurilemomas, schwannomas are the most common type of peripheral nerve tumor, although they are exceedingly rare in the breast. They are benign encapsulated tumors composed of neoplastic Schwann cells. These tumors grow slowly and eccentrically, with the peripheral nerve itself usually incorporated into the schwannoma capsule. Diagnosis is histologic: schwannomas demonstrate nuclear palisading (Verocay bodies) and biphasic architecture of Antoni A (dense) and B (loose) patterns, and a few pathologic variants have been described. Similar to neurofibromas and other tumors of neural origin, schwannomas are diffusely immunoreactive for S100. Schwannomas can arise in patients of all ages, and there is no predilection to gender or race. The majority are solitary and sporadic, although they can occur in association with NF2 or other genetic syndromes. Most patients are asymptomatic, although dysesthesia, radicular-type pain, sensory loss, and weakness can occur due to nerve impingement. Schwannomas can have a similar appearance as neurofibromas on imaging—well circumscribed, hypoechoic, and heterogeneous—and frequently the two cannot be distinguished. Symptoms from schwannomas prompt surgical removal less often than in neurofibromas, but when surgery is necessary, outcomes are usually successful, with large preservation of neurologic function.

Myogenic Neoplasms

Leiomyoma

An exceedingly rare entity first described by Strong in 1913 and currently only reported in about 30 case studies, leiomyoma of the breast is a benign tumor that tends to occur in women of late middle age and is typically found in the subareolar region, which may be related to the abundance of smooth muscle cells around the nipple and areola. For unclear reasons, they occur more often in the right breast. Radiologically, leiomyomas appear as well-circumscribed solid masses without distal attenuation on ultrasound, which distinguishes them from FAs. Histologically, leiomyomas are characterized by interlacing bundles of spindle-shaped cells with blunt-ended nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Most stain positive for vimentin, desmin, and muscle-specific actin. Leiomyoma must be differentiated from leiomyosarcoma, which can either occur deep in breast parenchyma or superficially near the nipple-areola complex and has a propensity for local recurrence or distant metastasis. The divergent cytogenetic profiles of these tumors indicate that different molecular genetic mechanisms are at play. Leiomyoma growth may be stimulated by tamoxifen, or antiobesity drugs, such as sibutramine and orlistat. Treatment is complete excision to prevent recurrence.

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcoma is a rare breast malignancy that develops in women in their fourth to eighth decades of life. Myofibroblasts in the nipple-areolar complex may be a reason these tumors arise in this location. Histologically, leiomyosarcoma demonstrates a spindle cell proliferation with elongated blunt-ended nuclei and merging cytoplasmic processes, which create fascicles and whorled patterns. As in other sarcomas, histologic grade is dependent on cellularity, mitotic count, necrosis, and cellular atypia. Immunohistology shows expression of actin, smooth muscle actin, vimentin, desmin (focal), and occasionally cytokeratin (focal). Treatment is centered on surgical excision, although local recurrence and distant metastases are common, sometimes occurring as late as 15 years after surgery.

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) of the breast mostly represents a metastasis from an extramammary site. A 25-year review found that only 2% of non-PT primary breast sarcomas were RMS, whereas AS was the most common type. RMS differentiation may develop in malignant PT or metaplastic carcinoma. Both primary and metastatic pure RMS predominantly affect adolescent females, and histology overwhelming (>90%) shows an alveolar subtype, which is known as ARMS. Classic ARMS has loosely cohesive cells, producing spaces surrounded by fibrous septa. Solid-type ARMS consists of a solid sheet of cells. Both types contain small rounded cells with minimal cytoplasm. Immunohistology is required to confidently diagnose RMS. Myogenin is the most sensitive and specific stain; desmin, myoglobin, and myoD1 are also useful. Intracellular glycogen may also be seen. ARMS has a unique cytogenetic abnormality, t(2;13)(q35;q14), detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization, allows distinction of this entity from other sarcomas. Local recurrence and pulmonary metastases are not uncommon. Five-year survival with resected RMS and without metastatic disease is greater than 90% for stage I disease and falls to 80%, 70%, and 30% for stages II, III, and IV, respectively.

Osseous Neoplasms

Pure osteosarcoma of the breast is rare. Mean age in a large study was 64 years. Coarse calcification is seen mammographically. These calcifications produce a gritty sensation when tumor is sectioned. Osteosarcoma is often well demarcated and varies from hard to somewhat firm, depending on the amount of osseous differentiation. Microscopy shows malignant spindle, stellate, and variably pleomorphic cells that are intimately associated with osteoid production. Osteoid varies from thin, lacelike eosinophilic stroma to thick, bony trabeculae. Metaplastic carcinoma or malignant PT with heterologous chondro-osseous differentiation must be excluded. Treatment of osteosarcoma of the breast comprises wide local excision with clear margins or mastectomy. There are no standard guidelines on adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy, and given limited breast-specific data, providers should follow those for soft tissue sarcomas in general. Early recurrence and survival less than 2 years is not uncommon.

Primary Breast Lymphoma

Primary extranodal lymphoma has been described for several organs that contain lymphoid tissue, including the skin, bone, brain, gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, testis, Waldeyer ring, and breast. Primary lymphoma of the breast, which arises from resident stromal lymphocytes, is an uncommon entity. Only a few hundred cases of primary breast lymphoma (PBL) have been reported in retrospective series, and only two prospective studies has been identified. PBL comprises only 0.5% of all breast malignancies and about 1% to 2% of extranodal lymphomas, and the most common histology is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

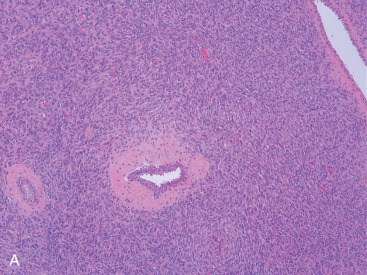

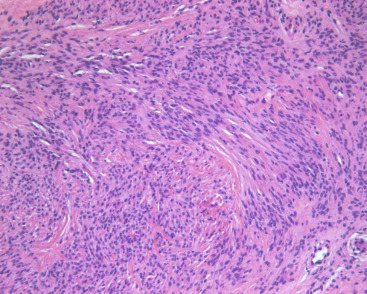

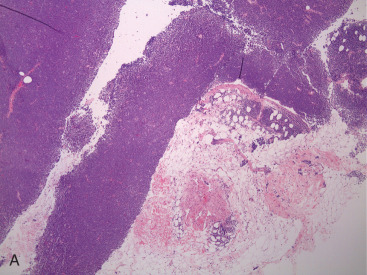

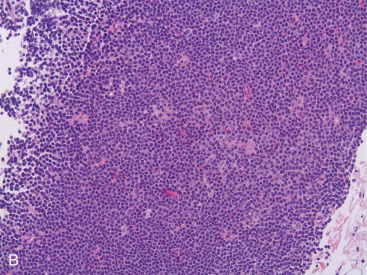

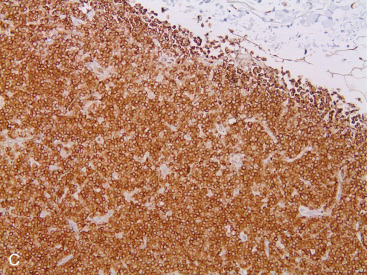

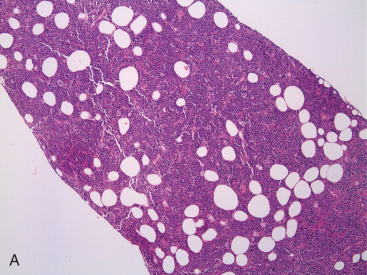

PBL may be accurately diagnosed when the breast is the first major site of lymphomatous involvement and there is no evidence of concurrent systemic disease. Morphologically, there are no differences between primary and secondary breast lymphoma, but it is important to distinguish between the two. The definition of PBL, as outlined by Wiseman and Liao in 1972 and modified by Hugh and colleagues in 1990, is still applied widely and requires that several criteria are fulfilled: adequate histopathologic evaluation; the lymphomatous infiltrate must be in close association with mammary tissue; and systemic lymphoma or antecedent extramammary lymphoma must be excluded, although ipsilateral axillary lymph node involvement is acceptable. Thus PBL is, by definition, limited disease by Ann Arbor staging. However, a strong case can also be made to include patients with regional lymph node (supraclavicular and internal mammary) involvement. In fact, the 2004 World Health Organization reclassification of breast lymphoma determines that disease is primary if the breast is the main lesion, regardless of stage or involvement of other organs. Accordingly, some researchers consider PBL to be lymphoma occurring in or localized to the breast tissue, even though there may be diffuse disease. Breast lymphoma is considered secondary when the breast is involved but not the predominant lesion in the setting of widespread systemic lymphomatous disease. Such would be the case in chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with secondary involvement of the breast ( Fig. 11.9A–C ). In many situations of advanced lymphoma where there is both breast and systemic involvement, it is impossible to determine which came first.

Clinical Features

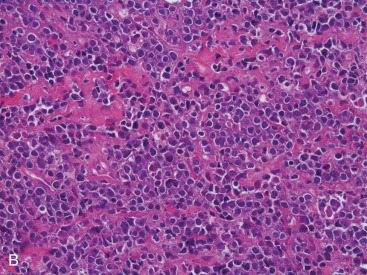

PBL most frequently occurs in women (98%) between 60 and 64 years of age in Western countries, although there is a broad range of ages reported in the literature. The female predominance suggests a hormonal role in the etiology of PBL. However, PBL does rarely occur in men: 1 in 23 patients in an MD Anderson series and 1 in 25 PBL patients at Mayo Clinic were male. Although the data are limited, outcomes in men appear similar. Interestingly, when PBL arises in younger or pregnant women, it is more often bilateral and more often exhibits features of a Burkitt or Burkitt-like lymphoma ( Fig. 11.10A–C ). Contralateral relapse occurs in up to 15% of cases, which suggests a possible malignant clone or a homing mechanism. The mechanism of this organ-specific relapse may be mediated by cellular receptors and tissue chemoattractants such as CXCL12 and CXCL13, which has been described in other extranodal lymphomas.

Most breast lymphomas present as a painless, mobile, enlarging mass in the outer quadrants. Diffuse hypertrophy and noncalcified lumps are usually associated. Breast lymphomas tend to be larger than epithelial breast cancers, and the average size is 4 cm, although they can range up to 20 cm. Interestingly, for unclear reasons, the right breast is more frequently involved than the left breast. Although uncommon, patients may present with respiratory symptoms, bulky lymphadenopathy, “B” symptoms, and central nervous system (CNS) symptoms, or other constitutional symptoms usually representative of disseminated disease. Nipple retraction, discharge, and skin manifestations (e.g., peau d’orange, indicating dermal lymphatic infiltration) are rare in PBL.

Diagnosis and Staging

Radiologic Features

Lymphoma of the breast is frequently well defined and circumscribed on mammography and may be difficult to distinguish from other tumor types. Some differences in the mammographic appearance of PBL compared with breast carcinoma have been reported, including larger size (4–5 cm in lymphoma vs. 2–3 cm in carcinoma) and absence of spiculation, calcification, and architectural distortion in the surrounding tissue. A typical radiographic appearance of PBL is a well-circumscribed, oval-shaped mass without calcification. However, mammographic findings may range from a discrete, well-circumscribed nodule with benign features, to a lesion with spiculated borders, and thus no radiologic features are truly specific for PBL and biopsy remains mandatory. Patients with PBL may even have normal mammography. Breast ultrasound features also can vary and quite often reveal hypoechogenicity with well-defined borders that lack significant acoustic shadowing. It should be stressed, however, that PBL can have a wide spectrum of appearances on ultrasound. Breast MRI may show characteristic findings, such as strong enhancement with penetrating vessels in masses on early-phase dynamic MRI, strong high intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging, a cerebroid appearance, and septal enhancement. These may offer diagnostic clues, but overall, PBL does not exhibit any obvious radiographic features that help differentiate it from other breast lesions. Fluoro( F)-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) imaging is, on the other hand, a useful tool to help ascertain lymph node avidity and stage, and is also used to follow treatment response. PET-CT scans maintain a sensitivity of 89% to 97% and specificity of 100% for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease and thus has an important role in imaging PBL as well. PET-CT also has a high sensitivity in detecting local recurrence and can thus be used in posttreatment restaging.

Excisional biopsy is needed for correct diagnosis of PBL, as in nodal lymphomas. Preservation of architecture is important to determine non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtype. Thus fine-needle aspiration and cytology, although they can differentiate between lymphoma and carcinoma, are insufficient for diagnosis. Imaging-guided core biopsy is acceptable if excisional biopsy is not possible. Histologic, ICH, and increasingly, genetic studies, are necessary to correctly establish the diagnosis of PBL. For example, the BRAF V600 mutation has been recently described for positive identification of hairy cell leukemia, and thus tumor genomic analysis can be used in diagnosing this rare subtype of PBL, along with the characteristic nuclear positivity for cyclin D1 and cytoplasmic positivity for annexin, TRAP, and weak CD25.

Staging.

PBLs are staged similar to other non-Hodgkin lymphomas, using the Ann Arbor staging system. Because the definition of PBL requires the lymphoma to be limited to the breast or ipsilateral lymph nodes, disease is most commonly classified as stage IE or IIE (i.e., limited stage). Most patients at diagnosis are stage IE (70%), while 30% have regional nodal involvement and are stage IIE. Clinical and radiographic assessment of the contralateral breast is mandatory because PBL is bilateral in 4% to 13% of patients at diagnosis, and cumulative incidence approximates 30%. Bilateral PBL appears to have a more aggressive course and poorer prognosis, and expert opinion is divided in terms of classifying bilateral PBL as stage IIE versus stage IV. Moreover, because PBL can occur synchronous with breast carcinoma, appropriate biopsies of any suspicious breast mass should be obtained. Minimum recommended studies of staging include a core or excisional biopsy; PET-CT scan; bone marrow biopsy; and lumbar puncture for CSF for cytology and flow cytometry. Basic laboratory studies should include a complete blood count with differential, serum chemistries, liver blood tests, and lactate dehydrogenase. Further imaging such as brain MRI should be obtained if neurologic manifestations are present. Multidisciplinary discussion among pathologists, radiologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and surgeons is imperative to ensure correct diagnosis and optimal management of these patients.

Risk Factors/Pathogenesis

Many potential risk factors for the development of PBL have been proposed, but none are definitively causative or associative. The presence of breast cancer itself may increase risk for breast lymphoma, given the number of reported cases of synchronous PBL with invasive ductal carcinoma. Case reports of PBL arising after treatment for breast carcinoma imply metachronous disease due to tissue damage, inflammation, and possible changes in the microenvironment and also implicate chemotherapy and/or radiation exposure as possible risk factors for PBL. Histologic transformation from low-grade lymphoma to higher-grade PBL has been proposed, given the presence of overlapping morphologic features in single specimens or based on cytogenetics. Immunodeficiency or an immunosuppressed state, even induced by the lymphoma itself and infection, such as by Epstein-Barr virus or the mouse mammary tumor virus, which induces WNT1 gene expression in both breast cancer and lymphoma, have also been postulated as risk factors. Autoimmune disease may also have a potential role in the pathogenesis in PBL. Several cases of PBL with antecedent autoimmune disease have been reported, and the increased risk of NHL in patients with connective tissues disease and autoimmune disorders is well documented.

The strong female predominance in PBL implies a role for estrogen in lymphomagenesis, and although epidemiologic evidence for estrogen as a risk factor for lymphoma are mixed, a large study by Teras and coworkers revealed an increased risk of almost 30% for NHL (but not specifically PBL) in women treated with estrogen replacement therapy (ERT), compared with women not exposed to ERT. The beta-isoform of the estrogen receptor (ER-beta) is found on lymphoma cell lines, and in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that selective ER-beta agonists have antiproliferative effects in ER-beta expressing lymphomas. Further investigation into the clinical effects of ER-beta agonists in PBL is needed. Several cases of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL, T-cell variant) have been described in association with breast implants; compiled data indicate that women with implants have a very small risk of developing ALCL and should be counseled about this. The ALCL that arises in the setting of breast implants tends to be more indolent compared with other PBLs.

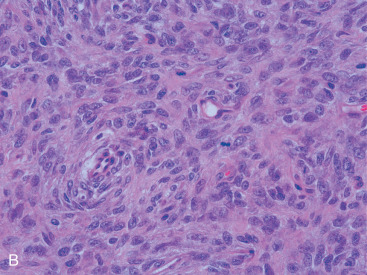

Pathology

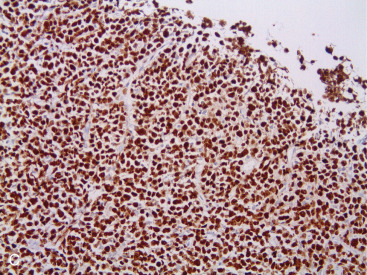

Most PBLs are non-Hodgkin lymphomas, representing approximately 1% of all NHLs. The majority of PBLs are B-cell lymphomas, and the most common histologic type is DLBCL ( Fig. 11.11A–C ). Intermediate- and high-grade histologies predominate. After DLBCL, extranodal marginal zone lymphomas ( Fig. 11.12A–C ) including those of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphomas), and follicular lymphoma of the breast have been described. Rarer (<1% each) are primary breast mantle cell lymphoma ( Fig. 11.13A–C ), Hodgkin disease, and hairy cell lymphoma. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma of the breast is extremely rare, but T-cell ALCL is now well described in association with breast implants, as mentioned earlier.