Abstract

Breast abscess is a common clinical problem. Management of these patients can be challenging and requires an understanding of pathophysiology and microbiology to achieve optimal outcomes. This chapter also highlights management considerations for granulomatous mastitis, periductal mastitis, and lactational abscesses

Keywords

mastitis, breast abscess, lactational abscess, periareolar abscess, idiopathic granulomatous mastitis

Management of patients with a breast abscess is an art, and each abscess has unique features that require familiarity by the treating physician. Breast abscesses can be frustrating for both the patient and the surgeon. Even for patients referred with chronic, recurring abscesses, the surgeon should initially repeat the breast conservative treatment that may have failed in the past, the purpose of which is to “get to know” the abscess and the patient. Knowing the personality of the patient is important because, on rare occasions, a simple mastectomy may be the last alternative to the patient’s ability to live without recurrent breast abscesses.

Mastitis

Mastitis is an infection of the breast that presents as pain, redness, and swelling. An infection of the breast parenchyma that goes unnoticed or untreated can eventually develop into an abscess. Patients with acute mastitis and abscess formation often represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Some abscesses drain spontaneously, and others require intervention that can include needle aspiration, incision and drainage, or excision. There is currently no consensus on optimal management strategies. The principles that guide successful diagnosis, evaluation, and management of various types of primary breast infections are discussed in this chapter.

Presentation

Patients with acute breast infection typically present with one or more of the following symptoms: skin erythema, palpable mass, tenderness, fever, and/or pain. Breast abscesses may occur in both the lactational and nonlactational settings. Breast abscesses have been most commonly reported to occur in women between 20 to 50 years of age. However, breast infections have also been reported in men, postmenopausal women, and children. Postmenopausal patients with a breast abscess often have a more indolent presentation and may lack many of the classical findings of a traditional breast abscess. Abscesses may occur either centrally (subareolar or periareolar) or peripherally in the breast, usually in the upper outer quadrant where a majority of breast tissue is located. Breast infection can result from recent surgery, tattoos, or nipple piercing, but most causes are unknown. The incidence of breast infection associated with surgery is 5% to 10% and with nipple piercing is estimated the be as high as 10% to 20% in the months after the procedure.

Evaluation

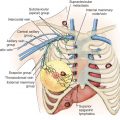

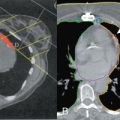

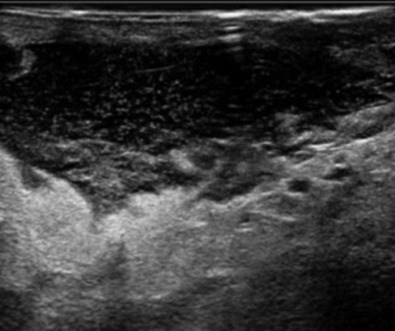

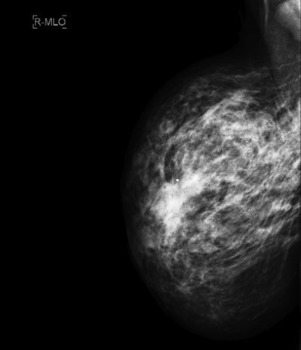

Careful clinical examination is the cornerstone of diagnosis for acute breast infection. Findings on examination can include a mass, erythema, skin warmth, skin thickening, and tenderness. ( Fig. 6.1 ) Ultrasound is a useful modality as an adjunct to physical examination to evaluate for the presence or absence of an associated underlying abscess. Additionally, ultrasound can help to identify the size and depth of the abscess cavity as well as the presence of multiple abscesses, which may not be appreciated on physical examination ( Fig. 6.2 ). Many patients with a breast abscess also have abnormal mammograms with nonspecific findings, including an irregular mass, focal asymmetry, diffuse asymmetric density, circumscribed mass, or architectural distortion ( Fig. 6.3 ). These findings in the acute setting may be difficult to differentiate from those findings associated with malignancy. In addition, in the acute setting of suspected breast infection, mammography is often not possible secondary to breast pain and tenderness. Importantly, in cases of atypical presentation or patients with recurrent, nonimproving symptoms, a mammogram should be performed to rule out inflammatory breast cancer. After successful medical, percutaneous, or surgical management and resolution of an acute breast infection or abscess, mammography to exclude an underlying or associated malignancy and to ensure complete resolution is recommended.

Microbiology

In the management of breast abscess, particular attention should be given to obtaining cultures for specific pathogens to help guide treatment decisions. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism associated with breast abscess. Recently, an increase in methicillin-resistant S. aureus has been detected in community-acquired breast infections. Other commonly reported causative organisms include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Proteus, Serratia, Bacteroides, and Kelbsiella. Of note, 20% to 40% of breast abscesses are found to be sterile on culture. Cigarette smoking has been associated with increased rates of anaerobic breast infections and increased rates of recurrent breast abscess. Pathologic organisms that have been documented after nipple piercing include aerobic, anaerobic, and mycobacterial infections. A variety of unusual pathologic organisms have been documented in association with breast abscess, including Actinomyces species , Brucella, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Fusarium solani, Echinococcus, and Cryptococcus. Many of these unusual infections are endemic to specific areas and specific patient populations, and they require special consideration in the appropriate clinical setting. Necrotizing soft tissue infections and gangrene of the breast have been reported in association with anticoagulant treatment, trauma, and in the postpartum period.

Management

Antibiotics

In patients who present with signs and symptoms of mastitis who are clinically suspected of having an underlying breast infection or abscess, ultrasound is useful for the detection of an intramammary fluid collection. For patients with no fluid or a small fluid collection seen on ultrasound, a trial of oral antibiotics is warranted. Initial choice of antibiotics is best directed by local antibiograms and to cover the most common pathogen S. aureus. Antibiotic recommendations include cephalexin 500 mg four times daily, dicloxacillin 500 mg four times daily, clindamycin 300 mg four times daily, with the optional addition of metronidazole 500 mg three times daily for 7 to 10 days’ duration. Failure to improve should prompt further evaluation with repeat ultrasound to evaluate for the development of an intramammary fluid collection requiring an alteration in the management strategy. In some cases, a tissue biopsy may be necessary to exclude malignancy. The patient should be scheduled for regular follow-up appointments until the infectious process has completely resolved.

Invasive Intervention

Early Abscess.

The traditional initial treatment approach of surgical incision and drainage of a breast abscess has been replaced by needle aspiration. Aspirated material should always be sent for microbiological analysis to allow for adjustments of the antibiotic regimen accordingly. Warm compresses placed over the abscess are recommended for comfort.

Aspiration.

Numerous authors have suggested aspiration of breast lactational and nonlactational abscesses as the primary management. Benefits of aspiration as an initial management strategy include improved cosmesis, lack of requirement for general anesthesia, no requirement for wound packing, and decreased cost. It has been reported to be successful in 54% to 85% of all cases. The described aspiration technique of several authors involves use a 16-gauge needle (or larger if necessary) with aspiration and irrigation of the cavity through an area where the skin is not thinned from inflammation. Use of ultrasound to guide aspiration may be helpful and is associated with higher rates of success but is not required, especially in superficial lesions. The addition of oral antibiotics is a necessary component of initial therapy for breast abscess managed with aspiration. Cultures of aspirated fluid may be useful to guide antibiotic choice. Although some authors have suggested sending abscess fluid for cytology to exclude malignancy, the value of this practice is not well defined and not widely recommended. Some authors have advocated instillation of antibiotics or saline irrigation into the abscess cavity ; however, this practice is not widely accepted, and its benefit has not been clearly demonstrated. Some have advocated placement of an indwelling drain at the time of aspiration, but this is also not routinely recommended. After initial management, patients should undergo at minimum biweekly clinical reassessment to determine resolution of the abscess or subsequent requirement for additional treatment (repeat aspiration or surgical drainage). Median time to resolution of breast abscess with aspiration is approximately 2 weeks (range, 1–8 weeks). Reported success rates for the aspiration technique are highest with repeated, multiple aspirations. Successful treatment for single and multiple aspirations of breast abscess are 57% to 79% and 90% to 96%, respectively. Patients who fail to improve with multiple aspirations or whose clinical condition deteriorates, require surgical incision and drainage. Factors that have been associated with failure of aspiration include large size (>3 cm) and presence of multiple loculations.

Surgical Intervention.

Surgical intervention in the form of incision and drainage should be performed for an abscess that has failed repeat aspiration. As with needle aspiration, this technique can be performed in the outpatient setting with use of minimal conscious sedation or local anesthetic. Use of conventional local anesthetic agents (e.g., lidocaine) is seldom effective in providing adequate local analgesia for the incision because of the low tissue pH in the inflamed skin tissue fluid, but should still be used. Additional options to make the patient comfortable include oral sedation in the office, administration of intravenous/intramuscular conscious sedation in the emergency department, or performing the procedure under general anesthesia in the operating room.

To perform incision and drainage, the incision should be made over the site of maximum fluctuance and kept within Langer’s lines for optimal cosmesis. The abscess cavity should be explored and all the loculi and septations broken down using either finger fracture technique or a hemostat. The abscess may be extensive or multilocular and must be drained completely, with care to not excise the surrounding indurated tissue so as not to destroy surrounding breast tissue or disfigure the breast. The purulent material should be cultured for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and a Gram stain should be performed. In the appropriate age group, a biopsy specimen of the abscess wall should be taken to rule out carcinoma. The abscess cavity should then be irrigated with normal saline solution. After irrigation of the abscess cavity, a gauze wick packing is placed to assist drainage and prevent premature skin closure. Tight packing should be avoided because it can cause necrosis of the tissue and overlying skin. Postprocedurally, antibiotics should be continued. The patient should be scheduled for biweekly follow-up appointments until the process has resolved. Final follow-up should include an ultrasound to document complete resolution.

Late Abscess.

The traditional approach to the large, chronic, deep breast abscess involves taking the patient to the operating room for surgical incision and drainage with disruption of septae and open packing of the wound to heal by secondary intention ( Fig. 6.4 ). Options to consider include use of operative ultrasound to identify all subclinical abscess pockets in the breast, pulse lavage, antibiotic-impregnated irrigation (such as gentamycin), and finger fracture or a hemostat to break up intervening loculations in the abscess cavity, packing the wound open with normal saline or iodine-soaked gauze or placement of a temporary dwelling Penrose drain. Planned return trips to the operating room and frequent follow-up should also be considered.

Limitations to this approach include need for general anesthesia, high cost of performing in an operating room, and patient’s understanding of potential prolonged healing, need for frequent packing/dressing changes, close follow-up, and risk of cosmetic deformity and recurrence. In addition, surgical incision and drainage have been associated with recurrence rates between 10% to 38% requiring additional procedures.

Principles of management of necrotizing soft tissue infection of the breast are similar to necrotizing soft tissue infections of other areas and include early diagnosis, early and aggressive surgical management, and systemic antibiotics. Because necrotizing soft tissue infections are most commonly polymicrobial in etiology, broad-spectrum antibiotics represent the best initial choice of antimicrobial coverage.

Lactational Mastitis and Abscess

A breast abscess that develops in the postpartum period is referred to as a lactational or puerperal abscess. This type of abscess tends to occur within the first 12 weeks after birth or at the time of weaning from breastfeeding. The patient presents with a tender breast mass, and is currently breastfeeding or has recently slowed frequency or stopped. In a lactational associated abscess, the pathogen is most often S. aureus. It remains unclear whether the staphylococci are derived from the skin of the patient or from the mouth of her suckling infant, and both may be sources of infection. Most lactation mastitis is a result of bacteria entry though a crack or sore in the skin of the nipple from feeding in combination with milk stasis from decreased frequency of breastfeeding. In milk stasis, the milk components can create a blockage of a lactiferous duct, resulting in retention of milk in the peripheral lobules creating a milk retention cyst called a galactocele. Usually, a galactocele does not become infected because the milk within the cyst is sterile, but this stagnant milk produces breast engorgement and in some cases can become infected.

The general principles for evaluation and management of breast infection, outlined previously, are applicable to lactational abscesses, and underlying malignancy must be excluded. Management consists of drainage (percutaneous or open) and systemic antibiotics. During treatment for lactational breast abscess, women are encouraged to continue to breastfeed, and this does not pose a risk to the infant. The breast with the abscess should be fully drained frequently via a breastfeeding or breast pump to prevent milk stasis and engorgement. Antibiotics given to a breastfeeding mother need to be nontoxic for an infant because these can be passed through the milk. Recommendations include any of the penicillin antibiotic regimens described earlier or ampicillin-sulbactam 875 mg twice daily for 10 days. Alternatives for a penicillin allergy include use of clindamycin 300 mg four times daily or azithromycin. If the mother requires antibiotics, which are not safe for a breastfeeding infant, the mother must be instructed to “pump and dump” her breast milk products until she has completed her antibiotic course.

Milk fistula is an uncommon condition, which can occur as a complication after a needle aspiration but more commonly after incision and drainage of a breast abscess in a lactating woman. In this situation, a fistula tract forms between the skin surface and the duct in the breast, resulting in spontaneous drainage of milk from this path of least resistance. Most milk fistulas will close primarily with time without the need for surgical intervention. On rare occasions, the mother will need to stop breastfeeding to allow the fistula to heal.

Periductal Abscess/Chronic Subareolar Abscess

In 1951 the association of a chronic, recurring periareolar breast abscess and an associated draining fistula was described by Zuska and colleagues and is often referred to as Zuska disease.

Presentation

Most patients who present are women aged 20 to 58 years, with a history of multiple recurrences of a periareolar breast abscess in the same location with the presence of a recurrent, chronic draining fistula at the edge of the areola. On occasion, associated nipple discharge or nipple inversion is observed. The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds based on presentation and history of recurrences.

On physical examination, the characteristic features are the presence of an acute breast subareolar abscess with accompanying local tenderness, swelling, erythema, and induration. The abscess is characteristically located at the edge of the areola, usually with an associated draining sinus tract located at the vermilion border of the areola ( Fig. 6.5 ). On examination, the finger-thumb test can be performed for evaluation of a subareolar mass, nipple discharge, or discharge from the fistula of the involved breast ( Fig. 6.6 ). Intermittent nipple discharge occurs in 8% to 84% of patients. Mammography and ultrasonography are helpful in detecting signs of prominent subareolar mammary ducts and to rule out an underlying mass or malignancy.

Causes

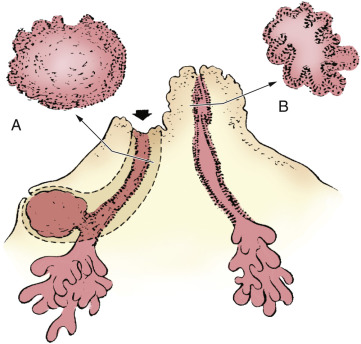

The cause and sequence of this benign disease process appears to be multifactorial, and the exact mechanism of the pathogenesis of this disease has been speculated. The disease progression hypothesis for a subareolar breast abscess is thought to begin with an abnormal change of the normal cuboidal lining of the lactiferous ducts into squamous metaplasia. The squamous epithelium then produces keratin, which in turn plugs the ducts, leading to obstruction. This accumulation of cellular debris produces dilatation of the duct and eventual rupture. The debris and secretory material infiltrate the surrounding tissue creating an inflammatory response in the breast tissue, and subsequent bacterial invasion results in abscess formation. Spontaneous drainage of the abscess occurs via the shortest and most direct route of least resistance, which is usually at the edge of the areola ( Fig. 6.7 ). Occasionally, the discharge also exits via the nipple. After the sinus has healed, in the vast majority of cases, the process continues and a recurrent abscess appears and discharges once more along the same route, establishing a permanent fistulous tract. Chronic fistulas have been reported to occur in 12% to 67% of patients. This is followed by the hallmark of this disease process—a recurrent subareolar abscess at a later date, either at the same site or in an adjacent segment of the breast. Until the underlying cause is identified and the entire diseased duct is completely removed, repeated episodes of infection are common and seldom self-limiting. Several authors have reported an association among cigarette smoking, vitamin A deficiency, or hormonal imbalances.

The main organisms cultured most commonly are mixed flora of aerobes and anaerobes consisting of S. aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Streptococcus, and anaerobes.

Factors

The development of a subareolar abscess is a spectrum of varying degrees of duct ectasia, followed by a primary chemically induced inflammatory reaction, and secondary bacterial growth, subsequently followed by an infection and chronic periductal inflammation. The development of a chronic mammary fistula is thought to be the final stage of a benign but complicated inflammatory process termed mammary duct–associated inflammatory disease sequence (MDAIDS). This concept is supported by the increased recognition and consensus that proper management of this disease entails use of a combination of antibiotics to cover aerobes and anaerobes followed by surgical excision of the involved duct and the associated periductal inflammation. The effect of hormonal (estrogen, prolactin), environmental (smoking), and nutritional (relative vitamin A deficiency) influences, as well as anatomic factors (congenital nipple retraction), is thought to play a contributory role to the development of subareolar abscesses. There is increasing epidemiologic and experimental evidence that vitamin A or retinoids have a significant biologic effect on mammary duct epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation. Many studies have also noted an increased incidence of mammary duct squamous metaplasia in smokers. The molecular mechanisms through which smoking induces squamous metaplasia have yet to be identified, although their association is strong, particularly in heavy smokers (more than 10 cigarettes per day). Interestingly, it has been shown that, within 30 minutes of smoking, nicotine and its metabolite cotinine are detected in the breast milk of lactating women. By its direct toxic effect, smoking can damage the subareolar ductal epithelium, making it easily prone to bacterial invasion from skin flora.

Treatment Plan

The approach to treatment of an active infection with a subareolar breast abscess should be determined by the degree of inflammation and existence of concurrent fistula. For an acute infection with abscess formation, initial treatment with antibiotics and either needle aspiration or incision and drainage is appropriate to clear the purulent infection as described earlier in this chapter. Perioperative antibiotic coverage should be employed, and the treating surgeon must recognize that this is only a temporizing measure. Broad antibiotic coverage should be considered to cover anaerobic and aerobic organisms. One option is using both cephalexin 500 mg four times daily and metronidazole 500 mg by mouth three times a day for 10 days; other options include amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium 875/125 mg twice daily, ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily, or sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 800/160 mg twice daily. It is anticipated that the infection will improve, but recurrence should be expected because the underlying disease process has not been eradicated. Definitive operative treatment of the abscess and the associated duct should then be planned for 4 to 6 weeks after the acute inflammatory process has subsided.

Surgical Management

When the fistula is chronic and well established, the patient should undergo surgery, usually with general anesthesia and continued antibiotic coverage. Surgical management requires complete excision of the fistula tract; diseased duct and surrounding inflamed tissue. Numerous different surgical techniques have been described.

Ductectomy

When only an isolated single duct appears to be involved in the disease process, the operative procedure recommended is called a ductectomy. With use of general anesthesia, this surgical technique involves placement of a lacrimal ductal probe into the fistula opening to define the fistula tract. This identifies the connection between the discharging duct in the nipple and the draining sinus at the edge of the areola ( Fig. 6.8 ). Alternately, injection of the fistula tract with 1% methylene blue before the start of the dissection is often helpful in identifying the corresponding major subareolar duct that connects with the fistula. Next, a radial elliptical incision is made to include the skin of the nipple and overlying areola including the entire involved duct and fistula tract as well as the inflamed tissue, resected back to normal tissue. The radial incision is made starting from the middle of the nipple and extending laterally through the areola and the vermilion border. After the entire diseased portion of the duct and surrounding tissue is removed, the nipple areolar complex is carefully reconstructed by placing 4-0 absorbable suture material subcutaneously at three critical sites: (1) the circumferential edge of the apex of the nipple, (2) the base of the nipple, and (3) the vermilion border of the areola. In patients who present with inverted nipples or a retracted nipple secondary to a previously drained chronic disease site, the nipple is everted, and a fourth suture consisting of a purse-string or Z-suture is placed inside the base of the nipple to prevent it from collapsing.