Introduction

This chapter outlines some specific conditions that are associated with diabetes. They are often managed in specialised services and some are very rare. A basic knowledge about these conditions can alert nurses to the possibility that they could be present, allow appropriate nursing care plans to be formulated and facilitate early referral for expert advice, which ultimately improve the health and well being of the individual.

The conditions covered in this chapter are:

- Enteral and parenteral nutrition

- Diabetes and cancer

- Smoking and alcohol addiction

- Brittle diabetes

- Oral conditions

- Liver diseases

- Breast mastopathy

- Coeliac disease

- Musculoskeletal disorders

- Corticosteroid medications and diabetes

- Diabetes and driving

ENTERAL AND PARENTERAL NUTRITION

The policies and procedures of the health service facility should be followed when caring for people with central lines, PEG tubes, and nasogastric tubes.

Enteral and parenteral nutrition is used to supply nutritional requirements in special circumstances such as malnourished patients admitted with a debilitating disease and where there is a risk of increasing the malnourishment, for example, fasting states. Malnourishment leads to increased mortality and morbidity thus increasing length of stay in hospital (Middleton et al. 2001). Often the patient is extremely ill or has undergone major gastrointestinal, head or neck surgery, or has gastroparesis diabeticorum, a diabetes complication that leads to delayed gastric emptying and can result in hypoglycaemia due to delayed food absorption, bloating, and abdominal pain. Alternatively, hyperglycaemia can occur. Gastroparesis is very distressing for the patient (see Chapter 8).

Aims of therapy

Complications of enteral nutrition

Routes of administration

Enteral feeds

This route supplies nutrients and fluids via an enteral tube when the oral route is inadequate or obstructed. Feeds are administered via a nasogastric, duodenal, jejunal or gastrostomy tube.

Enteral feeding is preferred over parenteral feeding when the gut is functioning normally and oral feeds do not meet the patient’s nutritional requirements (McClave et al. 1999). Nasogastric tubes may be used in the short term. Nasogastric feeds have a significant risk of pulmonary aspiration. The tubes are easily removed by confused patients and cause irritation to the nasal mucosa and external nares that can be uncomfortable and is an infection risk in immunocompromised patients and hyperglycaemia.

Duodenal and jejunal tubes do not carry the same risk of pulmonary aspiration but the feeds can contribute to gastric intolerance and bloating, especially in the presence of gastroparesis.

Gastroscopy tubes are used in the long term when the stomach is not affected by the primary disease. This may preclude their use in people with established autonomic neuropathy that involves the gastrointestinal tract. The tubes can be inserted through a surgical incision and the creation of a stoma. More commonly, percutaneous endoscopic techniques (PEG) are used (Thomas 2001). Inserting a PEG tube involves making an artificial tract between the stomach and the abdominal wall through which a tube is inserted. The tube can be a balloon tube or a button type that is more discrete and lies flat to the skin. An extension tube is inserted into the gastroscopy tube during feeding.

Gastrostomy (PEG) feeds

Feeds can usually be undertaken 12–24 hours after the tube is inserted but can be given as early as 4–6 hours after tube insertion in special circumstances. The initial feed may be water and or dextrose saline depending on the patient’s condition.

Mode of administration

The strength of the feeds should be increased gradually to prevent a sudden overwhelming glucose load in the bloodstream. An IV insulin infusion is an ideal method to control blood glucose levels. Blood glucose monitoring is essential to gauge the impact of the feed on blood glucose and appropriately titrate medication doses.

The feeds usually contain protein, fat, and carbohydrate. The carbohydrate is in the form of dextrose, either 25% or 40%, and extra insulin may be needed to account for the glucose load. A balance must be achieved between caloric requirements and blood glucose levels. Patients who are controlled by OHAs usually need insulin while on enteral feeding.

Parenteral feeds

This is administration of nutrients and fluids by routes other than the alimentary canal, that is intravenously via a peripheral or central line.

Mode of administration

Parenteral supplements are either partial or total.

Choice of formula

The particular formula selected depends on the nutritional requirements and absorptive capacity of the patient. It is usual to begin with half strength formula and gradually increase to full strength as tolerated. The aim is to supply adequate:

- fluid

- protein

- carbohydrate

- vitamins and minerals

- essential fatty acids

- sodium spread evenly over the 24 hours.

Nutritional requirements can vary from week-to-week; thus, careful monitoring is essential to ensure the formula is adjusted proactively and appropriately.

Diabetes medication, insulin or oral agents, are adjusted according to the pattern that emerges in the blood glucose profile. The dose depends on the feeds used as well as other prescribed medicines, and the person’s condition. Generally, the insulin/OHA doses are calculated according to the caloric intake.

Nursing responsibilities

Care of nasogastric tubes

Care of PEG tubes

The same care required for nasogastric tubes applies. Additional care:

Care of IV and central lines

General nursing care

Care when recommencing oral feeds

DIABETES AND CANCER

Diabetes has been linked to various forms of cancer but the relationship is not straightforward. There appears to be an increased risk of cancer of the pancreas, liver, and kidney (Wideroff et al. 1997). Endometrial cancer also appears to be associated with diabetes and obesity (Wideroff et al. 1997). Diabetes may be an early sign of pancreatic cancer (Vecchia et al. 1994). A recent study demonstrated a significant increased risk for all cancers at moderately elevated HbA1c levels (6–6.9%) with a small increased risk at high levels (>7%) (Travier et al. 2007). These findings support the hypothesis that abnormal glucose metabolism is associated with an increased risk of some cancers but may not explain the mechanism.

Researchers have also suggested diabetes is an independent predictor of death from colon, pancreas, liver, and bladder cancer and breast cancer in men and women (Coughlin et al. 2004). Verlato et al. (2003) reported increased risk of death from breast cancer in women with Type 2 diabetes compared with non-diabetics and suggested controlling weight reduced the mortality rate. Likewise, median survival time is shorter (Bloomgarden 2001).

The management of the cancer itself is the same for people with diabetes as for other people; however, some extra considerations apply. Cancer cells trap amino acids for their own use, limiting the protein available for normal body functions. This sets the scene for weight loss, especially where the appetite is poor, and the senses of smell and taste are diminished. Weight loss is further exacerbated by malabsorption, nausea and vomiting, and radiation treatment. While weight loss may confer many health benefits it is often excessive in cancer and causes malnutrition, which reduces immunity and affects normal cellular functioning and wound healing. Glucose enters cancer cells down a concentration gradient rather than through insulin-mediated entry and metabolism favours lactate production that is transported to the liver, increasing gluconeogenesis. Hypoalbuminaemia also occurs.

For the person with diabetes this can contribute to hyperglycaemia and reduce insulin production, with consequent effects on blood glucose control. Hyperglycaemia is associated with higher infection rates and the risk is significantly increased in immunocompromised patients and those on corticosteroid medications.

Diabetic management should be considered in relation to the prognosis and the cancer therapy. Preventing the long-term complications of diabetes may be irrelevant if the prognosis is poor, but controlling hyperglycaemia has benefits for comfort, quality of life, and functioning during the dying process (Quinn et al. 2006). However, many people have existing diabetes complications such as renal and cardiac disease that need to be considered. For example, the chemotherapeutic agent cisplatin causes renal insufficiency and can exacerbate existing renal disease; cisplatin, paclitaxel, and vincristine might exacerbate neuropathy. Side effects from chemotherapeutic agents are usually permanent. Where the prognosis is good, improving the complication status as much as possible and controlling blood glucose and lipids may help minimise the impact of chemotherapy.

Specific treatment depends on the type of cancer the patient has. Diagnosis of some types of cancer (e.g. endocrine tumours) can involve prolonged fasting and radiological imaging and/or other radiological procedures. The appropriate care should be given in these circumstances (see Chapter 9).

Corticosteroid therapy is frequently used in cancer treatment and can precipitate diabetes. Corticosteroids may be required for a prolonged time or given in large doses for a short period. Corticosteroids cause hyperglycaemia even in people without diabetes. Therefore, blood glucose needs to be monitored regularly in patients on corticosteroid medications, which are discussed later in this chapter.

Objectives of care

Primary prevention

People with chronic diseases such as diabetes often do not receive usual preventative health strategies such as cancer screening (Psarakis 2006). For example, Lipscombe et al. (2005) found Canadian women with chronic diseases were 32% less likely to receive routine cancer screening even though their doctors regularly monitored them. The discrepancy in screening rates could not be explained by other variables.

Proactive cancer screening and prevention programmes are important and should be promoted to people with diabetes, for example, mammograms, breast self-examination, and prostate checks. The findings also highlight another indication for normoglycaemia, controlling lipids, and weight management. Preventative health care also needs to encompass smoking cessation, reducing alcohol intake, and appropriate exercise and diet.

In addition to the specific management of the cancer indicated by the cancer type and prognosis, diabetes management aims are:

Nursing responsibilities

Managing corticosteroids in people with cancer

People with cancer are often prescribed glucocorticoids as a component of chemotherapy to prevent or manage nausea, reduce inflammation or following neurological procedures. These medicines cause postprandial hyperglycaemia by downregulating GLUT-4 transporters in muscle, which impairs glucose entry into cells. They also promote gluconeogenesis. Not all glucocorticoids have the same effect on glucose. The effect depends on the dose, duration of action, and duration of treatment. Morning prednisolone doses usually cause elevated blood glucose after meals but the blood glucose usually drops overnight and is lower in the morning.

Complementary therapies and cancer

Many people with cancer use a variety of complementary therapies (CAM). Estimates vary from 7% to 83%: mean 31%. High usage occurs in children, older people, those with specific cancers such as prostate and breast cancer (Fernandez et al. 1998; Wyatt et al. 1999; Kao & Devine 2000; Boon et al. 2000). The type of CAM therapies used varies among countries and ethnic and cultural groups. Distinctive characteristics of CAM users with cancer include:

- Women.

- Younger age.

- Higher education.

- Higher socioeconomic group.

- Prior CAM use.

- Active coping and preventive health care behaviours and a desire to do everything possible to maintain or improve health and quality of life, as well as take an active part in management decisions.

- Participation in cancer support groups.

- Having a close friend or relative with cancer.

- Changed health beliefs as a consequence of developing cancer.

Many conventional practitioners are concerned that CAM holds out false hope of a cure, interferes with or delays conventional treatment, the risk of CAM medicine side effects and interactions, and because not all CAM is evidence based. Many of these concerns are well founded. Chapter 19 discusses CAM in more detail.

Where CAM is used it needs to be integrated into the care plan to optimise the benefits of both CAM and conventional management strategies. Some benefits include longer survival time and improved quality of life using mind body medicine (Spiegal et al. 1989; Wolker et al. 1999); and reduction in chemotherapy induced stomatitis (Oberbaum et al. 2001).

Useful CAM strategies include:

- Mind body therapies such as relaxation techniques, meditation, massage, and creative therapies such as music, art, and writing.

- Gentle exercise such as some forms of Tai Chi, walking that can include pet therapy (e.g. walking the dog).

- Essential oils can be used in psychological care as well as massage and education and some reduce stomatitis (Wilkinson 2008). The oils need to be chosen to suit the individual because some odours contribute to nausea or may provoke unpleasant memories. Alternatively they can recall happy memories.

- Nutritional medicine that focuses on a healthy well balanced diet, whole foods, low in fat and sugar and using vitamin and mineral supplements especially in immunocompromised patients if they are not contraindicated. Probiotics can help sustain normal gut flora. Soy products and vitamin D supplementation improve bone mineral density.

- Acupressure to acupuncture point P6 reduces nausea, and is a useful addition to conventional methods of controlling nausea (Dibble et al. 2007).

- Herbal medicines such as milk thistle complement the action of chemotherapy and reduce the toxic effects on the liver in animal models (Lipman 2003) and antiinflammatory agents such as curcumin.

Since the introduction of serotonin inhibitors, for example, Ondansetron, to control nausea and vomiting, these effects of chemotherapy have decreased. Consequently there is less disruption of normal eating patterns.

SMOKING, ALCOHOL, AND ILLEGAL DRUG USE

Substance use refers to intentionally using a pharmacological substance to achieve a desired effect: recreational or therapeutic. The term ‘use’ does not imply illegal use and is non-judgmental. However, the term ‘substance abuse’ is both negative and judgmental. Continued drug abuse can become an addiction. The American Psychiatric Association (2000) defined criteria for diagnosing psychiatric disease including drug abuse and drug addiction, see Table 10.1.

Smoking

Giving up smoking is the easiest thing in the world. I know because I’ve done it thousands of times.

(Mark Twain)

The prevalence of smoking has decreased in many countries but smoking continues to be the most common morbidity and mortality risk factor (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2006). Smoking is hazardous to health regardless of whether the individual has diabetes or not. In addition, constantly being in a smoke filled environment is a hazard for non-smokers causing ~50 000 death annually in the US (Surgeon General’s Report 2006). Smoking during pregnancy has adverse effects on the fetus as well as the mother’s health.

Nicotine is the primary alkaloid found in tobacco and is responsible for addiction to cigarettes. Tobacco also contains ~69 carcinogens in the tar, the particulate matter that remains when nicotine and water are removed, 11 of these are known carcinogens and a further 7 are probably carcinogens (Kroon 2007). Of these, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) are the major lung carcinogens and are potent hepatic cytochrome P-450 inducers, particularly 1A1, 1A2 and possible 2E1. Thus smoking and quitting can interact with commonly prescribed medicines and foods. Smoking status is an important aspect of routine medication reviews and prescribing.

Table 10.1 American Psychiatric Association criteria for drug abuse and drug addiction. Drug abuse is diagnosed when a person exhibits three of these criteria for 12 months.

| Criteria for drug abuse | Criteria for drug dependence/addiction |

| Recurrent drug use and not fulfilling important/usual life roles. | Tolerance Withdrawal symptoms when not using. |

| Using drugs in dangerous situations. | Taking increasing amounts over time and for longer than intended (needing more drug to achieve and effect). |

| Encountering legal problems from using drugs. | Wanting to or unsuccessfully trying to reduce use or quit. |

| Continuing to use drugs despite encountering problems. | Spending a considerable amount of time obtaining, using or recovering from drug use. Usual activities are affected by drug use. Continuing to use despite knowing it is harmful. |

Interactions occur between tobacco smoke and many commonly prescribed medicines. With respect to diabetes these include:

- Subcutaneous and inhaled insulin. Absorption of subcutaneous insulin may be reduced due to insulin resistance, which is associated with smoking. Inhaled insulin is rarely used. Smoking enhances absorption rates and peak action time is faster and insulin blood levels are higher than in non-smokers.

- Propanolol and other beta blocking agents.

- Heparin: reduced half-life and increased clearance.

- Hormone contraceptives particularly combination formulations.

- Inhaled corticosteroids, which may have reduced efficacy in people with asthma.

- Tricyclic antidepressants.

- Other medicines such as olanzapine, clozapine, benzodiazepines, and opoids (Zevin & Benowitz 1999).

Other medicines and foods may also be affected leading to less than optional therapeutic effects and subtle malnutrition. Dose adjustments of many medicines may be required when people smoke and may need to be readjusted once they quit. The side effects of medicines may contribute to withdrawal symptoms.

People most likely to smoke:

- Are members of some ethnic groups such as Indigenous Australians, African American, and Hispanics.

- Have a mental health problem, 70% of people with a mental health problem smoke. In addition, people often commence smoking when they develop a mental health problem.

- Use illegal drugs and/or alcohol.

Quitting smoking reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cancer and a range of other diseases, and dying before age 50 by 50% in the following 15 years. The risk of developing many of these conditions is increased in the presence of obesity and uncontrolled diabetes. Smoking in middle and old age is significantly associated with a reduction in healthy life years (Ostbye & Taylor 2004). A recent meta-analysis of observational studies suggests smoking increases the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes in a dose-dependent manner (Willi et al. 2007). Willi et al. found smoking was independently associated with glucose intolerance, impaired fasting glucose and Type 2 diabetes.

Quitting smoking is difficult and requires significant behaviour change on the part of the individual. In order to change, they must first recognise there is a problem and the scale of the problem. The desire to change may not be the same as wanting help to change. Almost 75% of smokers report they want to quit (Owen et al. 1992), but <7% remain smoke free after 12 months and the average smoker tries to quite 6–9 times in their lifetime (American Cancer Society 2007). Smoking at night appears to be a predictor of nicotine dependence and is a significant predictor of relapsing within 6 months of trying to quit (Bover et al. 2008). In addition, smoking at night is associated with poor treatment outcomes (Foulds et al. 2006). Bover et al. suggested health professionals should specifically ask about night smoking when assessing readiness to quit.

Research suggests timing smoking cessation interventions to coincide with the individual’s readiness to change is important to success. In addition, sociologists highlight the importance of life course transitions in behaviour change and suggest the longer people live the more likely they are to make transitions in later life and the more likely such transitions are to be accompanied by changes in behaviour (George 1993). Thus targeting smoking cessation interventions to coincide with life transitions may be more likely to succeed.

For example, Lang et al. (2007) suggest individuals retiring from work are more likely to stop smoking than those who remain at work after controlling for retiring due to ill health. They recommended interventions be developed for those making the transition to retirement and employers should incorporate smoking cessation programmes into their retirement plans. Health events, particularly those that are disabling or affect work and lifestyle also affect smoking cessation rates (Falba 2005). These and other studies suggest several key transitions that could be used target smoking cessation in addition to regular prevention messages.

Nicotine addiction

Nicotine receptors, α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), are located throughout the central nervous system. Nicotine binds to these receptors, and acts as an agonist prolonging activation of these receptors and facilitating the release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, and beta-endorphins, which engenders pleasurable feelings, arousal, reduced anxiety and relaxation. Nicotine action mode reinforces dependence in a cyclical manner: smoking stimulates dopamine, the dopamine level falls as the nicotine level falls producing withdrawal symptoms. Smoking again suppresses the cravings by restimulating the nAChRs receptors.

The area of the brain concerned with addiction appears to be the insula, a small structure within the cerebral cortex. People with damage to the insula from trauma or stroke often suddenly stop smoking and remain non-smoking (Naqvi et al. 2007). Five milligrams of nicotine per day is a large enough dose to cause addiction. Each cigarette contains between 0.13 and 2 mg of nicotine, thus even light smokers can be addicted. Nicotine is present in the blood stream within 15 seconds of smoking a cigarette, which provides immediate gratification (Watkins et al. 2000). Chronic nicotine use desensitises the receptors and increasing amounts of nicotine are required to achieve pleasurable effects.

Withdrawal symptoms usually occur within the first 24 hours and can be very stressful. Withdrawal symptoms include:

- Craving tobacco.

- Difficulty concentrating, which affects work and usual daily activities.

- Headache.

- Impaired motor performance.

- Fatigue.

- Irritability.

- Anxiety and restlessness.

- Sleep disturbances.

- Nausea.

- Hunger and weight gain. Concern about putting on weight can be a barrier to quitting.

All of these symptoms can lead to neglect of diabetes self-care. Smoking cessation programms need to help the individual manage these symptoms.

Assisting the person to stop smoking

Brief advice from general practitioners (GPs) and other health professionals has a limited effect: only 2–3% quit per year (Lancaster & Stead 2004) but the effect size can be increased if other strategies are also used. These include referral to Quitline, interested supportive follow up, setting achievable goals and pharmacotherapy. The 5As approach can be helpful. It consists of:

Ask about smoking habits and systematically document the information at each visit. Provide brief advice to quit in a clear supportive, non-judgmental manner regularly.

Assess interest in quitting so that advice can be appropriately targeted to the stage of change and to opportunistically support attempts to quit. Assess whether the individual has tried to quit in the past and the factors that prevented them from quitting and those that helped, as well as the level of nicotine dependence: ~70–80% of smokers are dependent on nicotine and will experience withdrawal symptoms when they try to quit. Nicotine addiction is a chronic relapsing condition (Wise et al. 2007). Repeated efforts to quit can be demoralising and set up learned helplessness. Helping the individual manage the symptoms can support their attempt. Sometimes mental health problems become apparent when a person stops smoking, thus mental health should be monitored.

Advise about the importance of quitting on a regular basis and provide new information as it arises. Advice can include information about smoking risks and quit programmes. Advice is more useful if it is tailored to the individual. In Australia some health insurance funds offer member discounts to quit programmes such as Allen Carr’s EasyWay to Stop Smoking. This method consists of a combination of psychotherapy and hypnotherapy.

Assist those who indicate they want to quit by asking what assistance they feel would help them most, refer them for counselling, provide written information or recommend other therapies as indicated and follow up at the next visit. Relapsing after attempting to quit is common. Praise and support are essential as are exploring the reasons for relapsing and discussing strategies for continuing the quit process. Motivational interviewing can be a useful technique.

Arrange a follow-up visit preferably within the first week after the quit date (The US Public Health Service 2000). Some pharmaceutical companies offer support programmes through newsletters and Internet sites. Fu et al. (2006) showed 75% of relapsed smokers were interested in repeating the quit intervention (behavioural and medicines strategies) within 30 days of quitting, which highlights the importance of support and constant reminders. Advising and supporting partners may also be important.

Non-pharmacological strategies can be combined with the 5As. These include opportunistic and structured counselling that encourages the individual to think about the relevance of quitting to their life, helps them identify their personal health risks, and helps them determine the barriers and facilitators they are likely to encounter develop strategies to strengthen the facilitators and overcome the barriers.

Improving nutrition is important to health generally. Diets rich in tyrosine, tryptophane, and vitamins B4, B3, C, and magnesium, zinc, and iron may stimulate the dopamine pathway and help reduce the effects of nicotine withdrawal by increasing serotonin levels (Oisiecki 2006). Improving nutrition can also reduce oxidative damage, which is increased in smokers and help reduce weight gain.

CAM strategies may help manage withdrawal symptoms. These include acupuncture and acupressure to specific points to reduce the withdrawal symptoms (Mitchell 2008). Patients may be able to learn to self-stimulate specific acupressure points. Treatment consists of biweekly session for two weeks and then weekly for 2–6 weeks. Herbal preparations include green tea and lemon balm tea capsules, which improves focus and concentration and reduces anxiety without causing drowsiness; Ashwaganda capsules, an Ayurvedic medicine, which increases energy levels and wellbeing, Silymarin (milk thistle) before meals to control blood glucose and support the liver, flower remedies, melatonin and high-dose vitamin B. All of these interventions need to be combined with education, support, and counselling.

Self-help websites describe a time frame when symptoms resolve and people can expect to feel better, which gives them a goal to aim for. They also suggest some steps to stopping, which include:

- Make a firm decision to stop and ask for help without shame or guilt.

- Ask people who successfully quitted how they did it.

- Quit with a friend to support each other.

- Wash your clothes and air out the house to get rid of the smell and if possible avoid smoke filled environments.

- Write down the reasons you want to quit and the things that can help you succeed.

- Get information about all the quit options and decide which one/s is most likely to suit you.

- Set small achievable goals.

These strategies can be included in other strategies.

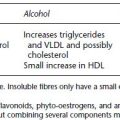

Medications to support smoking cessation

A number of medicines are available to assist smoking cessation but they are not a substitute for counselling and support, which need to continue if medications are indicated. Commonly used medicines to help people quit smoking are shown in Table 10.2. A combination of dose forms can be used, for example, patches and gums. In addition, nicotine replacement therapy can be prescribed for pregnant and lactating women but non-medicine options are preferred, people with cardiovascular disease, and young people aged 12–17 years (Tonstad et al. 2006).

Table 10.2 Medicines available to assist people to quit smoking. They should be combined with other counselling and support strategies and good nutrition and be considered as part of the medication record and their benefits and risks reviewed regularly while they are being used. The prescribing information should be consulted for specific information about each medicine.

Other medicines and an anti-nicotine vaccine are currently being developed to reduce the link between smoking and nicotine concentration in the brain to lower the related gratification. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) may be adapted in the future to specifically target the insula. Currently, TMS does not penetrate beyond peripheral tissues.

Alcohol addiction

Alcohol is also an addictive substance associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Between 15% and 20% of GP consultations relate to alcohol (Lee 2008). Shortterm consequences include injury and domestic violence; longer term effects include other risk taking behaviours such as smoking, neglected self-care, driving while intoxicated, cognitive impairment, peripheral neuropathy, liver cirrhosis, and fetal damage in pregnant women. Approximately 10% of Australians and 20% of Indigenous Australians drink more than the recommended level (National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2007). Young people are also likely to consume higher than recommended amounts of alcohol. Recommendations for alcohol intake were discussed in Chapter 1 and are defined in the draft NHMRC guidelines.

The criteria for alcohol dependence are three of the following seven features:

- Alcohol tolerance.

- Withdrawal symptoms.

- Drinking more than the recommended level or for longer than planned.

- Previous unsuccessful attempts to reduce consumption or stop drinking.

- Spending a significant amount of time procuring or drinking alcohol.

- Neglecting social interactions and work responsibilities because of alcohol.

- Continuing to drink despite the actual and potential health risks.

The strategies outlined for helping people quit smoking can be adapted to help people reduce alcohol consumption to the recommended levels or stop drinking. Screening for alcohol dependence can be accomplished using the World Health Organisation (WHO) Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders et al. 1993). High AUDIT scores indicate the need for a comprehensive intervention and counselling. Support groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous have a well-recognised role in stopping drinking and preventing relapse.

Diabetes is difficult to manage because oral hypoglycaemic agents are often contraindicated because of the risk of lactic acidosis (metformin) and hypoglycaemia. Insulin is often indicated but adherence is often suboptimal and is compounded by erratic intake and malnutrition. Withdrawal processes for heavy drinkers need to be supervised and people require a significant amount of support.

Medicines to assist alcohol withdrawal include acamprosate and naltrexon, which are generally well tolerated and can be continued if the person drinks alcohol. They are effective at preventing relapse, delaying return to drinking and reducing drinking days. Disulfiram (Antabuse) causes acute illness if the person drinks alcohol while taking the medication. Supervision is required if Antabuse is used because life-threatening reactions can occur. It is not the ideal first-line treatment and probably should only be prescribed by doctors with experience using it or use it under the guidance of such experts (Shand et al. 2003).

Illegal drug use

The effect of marijuana, cocaine, and other illegal drugs on diabetes is unclear. These substances are associated with poor health outcomes and risk-taking behaviours in non-diabetics and people with diabetes. In addition, illegal drugs and the associated risks may compound or contribute to short- and long-term diabetes complications. The fact that they are illegal makes illegal drug use harder to detect. Generally, illegal drugs fall into three main categories:

- Uppers, for example, ecstasy, ice, crystal meth, cocaine, snow, speed.

- Opiates, for example, morphine, heroin, smack.

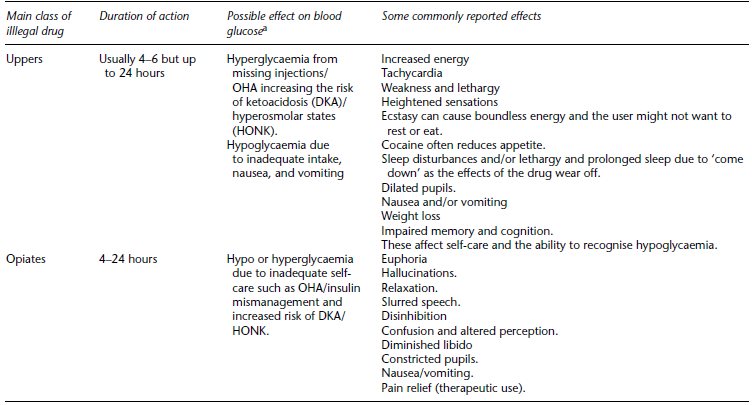

- Hallucinogens, for example, marijuana (cannabis, pot, weed), LSD, solvents such as petrol, glue, and paint. Table 10.3 outlines the effects of these substances and their impact on blood glucose.

In addition, many herbs have psychogenic properties. They may be stimulants, sedative, cognitive enhancing or analgesics as well as uppers, hallucinogens, or act in a similar way to opiates (Spinella 2005). Significantly, herbs may contain more than one chemical substance and are sometimes used to manufacture illegal drugs. Examples include but are not limited to:

- Acorus calamus (calamus). Ecstasy can be manufactured from calamus.

- Salvia divinorum

- Ephedra species

- Amantia muscaria (magic mushrooms)

- A herbal mixture called hoasia, yaje, or daime.

The effect of any drug depends on its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, bioavailability, and elimination. Thus, the effect depends on the administration route, how the individual metabolises drugs and is usually dose dependent. Common routes of illegal drug administration are:

- enteral

- oral

- sublingual

- rectal

- oral

- parenteral

- IV

- subcutaneous, for example, ‘skin popping’ heroin

- inhalation smoking, pipe, cigarettes, hookah.

Effects on diabetes

Illegal drugs appear to have two inter-related consequences for people with diabetes: physical effects, although the pharmacological effects on blood glucose appear to be minor (Glick 2008), effect on cognitive processes, which disrupt problem-solving, decision-making, and self-care. Cognitive effects are significant and contribute to erratic blood glucose control. They are also associated with other general health risks such as sexually transmitted disease, malnutrition, and reduced immunity, which impact on diabetes related well being.

As well as contributing to the development of long-term diabetes complication through inadequate self-care and hyperglycaemia, addiction to some illegal drugs exacerbate existing diabetes complications. Illegal drugs exert significant haemodynamic and electrophysiological effects. The specific effects depend on the dose, the degree of addiction (see Table 10.3), and the drug formulation. Marijuana, the most commonly used illegal drug, is associated with cerebrovascular events and peripheral vascular events (Moussouttas 2004) and atrial fibrillation and increased cardiovascular morbidity (Korantzopoulos et al. 2008). Smoking exacerbates the vascular effects and nerve damage may be exacerbated by excessive alcohol use.

Cardiovascular effects include:

- Slight increase in blood pressure especially in the supine position.

- Rapid tachycardia, most likely due to enhanced automaticity of the sinus node, which increases cardiac output and reduces oxygen carrying capacity due to increased carboxyhaemoglobin when smoking marijuana.

- Constriction of blood vessels increasing the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, for example, cocaine.

- Reduced peripheral vascular resistance but the extent varies in different peripheral sites.

- Angina and acute coronary syndromes especially in older people with postural or orthostatic hypotension.

Interactions with medicines

Information about interactions between illegal drugs and OHA and insulin is unclear but some drugs might affect OHA/insulin bioavailability. In addition, the different illegal drugs and the different dose forms (inhaled, smoked, intravenous, oral) are likely to have different pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics (Brown 1991). A significant problem is the fact that many such drugs are manufactured illegally and there are no quality control standard processes to ascertain purity, bioavailability, or the contents of the drug.

Management issues

Management is challenging and requires a great deal of tact and understanding. Referral to an appropriate ‘drug and alcohol’ service is advisable. Health professionals should be able to identify illegal drug use and refer early to reduce the likelihood of addiction developing, see Table 10.3. Strategies include:

- Providing an environment where patients feel safe and able to discuss difficult issues.

- Taking a thorough medical, work and social history, and monitoring changes.

Table 10.3 The effects of the drug or drug combination and duration of action depends on a number of factors including the dose and frequency of use and individual factors. Long-term use can contribute to psychiatric disorders and conversely psychiatric disorders can trigger illegal drug use. Illegal drugs can interact with conventional and/or complementary medicines and sometimes alcohol. All can lead to addiction, which has social, professional and financial implications and increases the risk of inadequate diabetes care, coma, and death.