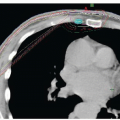

About half of patients with metastatic breast cancer develop liver metastases, a finding that generally portends a poor prognosis (

1): median overall survival (OS) of 4 to 22 months (

1,

2). Since liver metastases commonly occur in the setting of concurrent extrahepatic metastases, liver involvement is generally considered to be a manifestation of disseminated disease, and patients are usually treated with systemic therapy (

2) (see

Chapters 33 and

34). However, in modern studies a minority of patients manifests metastatic breast cancer limited to the liver (

1,

2). Localized, liver-directed treatments have achieved some success in other cancers, especially when disease is limited to the liver, and these approaches have been applied to breast cancer patients. Published studies have evaluated the safety and benefit of a range of liver-directed treatments: hepatic resection (

Table 81-1), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) with and without drugeluting beads, radioembolization, intraarterial chemotherapy, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), brachytherapy, and interstitial laser therapy (ILT) (

Table 81-2). However, the comparative efficacies of these approaches remain unknown because there are limited prospective studies and no randomized controlled trials (

Table 81-3). Furthermore, identifying appropriate patients remains a challenge, and the carefully selected patients in published series may represent good prognosis subgroups independent of the therapeutic approach.

Nevertheless, studies suggest that treatment of metastatic breast cancer limited to the liver may benefit some patients. In addition, as improvements in systemic therapies offer better control of metastatic disease and longer survival, more patients may need localized management of liver metastases. This chapter reviews localized, liver-directed treatment of hepatic metastases in breast cancer, details specific clinical considerations for each treatment option, and describes the available data for common and emerging approaches.