Abstract

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) exists as two main subtypes, classic and pleomorphic. While it may sometimes be an invasive cancer precursor, LCIS can be treated as a risk lesion without complete surgical resection. Bilateral mastectomy has been replaced with programs of surveillance. LCIS is usually discovered incidentally during biopsy for another indication. LCIS incidence appears to be influenced by the use of exogenous hormones. The lifetime risk of invasive cancer is 8 to 10 times that seen among women without LCIS. The risk of invasive cancer development can be decreased by the use of a chemopreventive endocrine agent. When diagnosed on a core needle biopsy, current guidelines recommend consideration of diagnostic surgical excisional sampling for discordant pathology/imaging findings, extensive LCIS, and/or when associated with other atypical findings to eliminate the possibility of a missed malignancy. Observation alone without excision is being offered to increasing numbers of individuals with classic LCIS on core sampling deemed concordant with imaging findings. Aggressive surgical resection of all disease at a surgical margin, even at the time of lumpectomy for a concurrent invasive tumor, is not advocated due to the fact that LCIS is often multicentric, multifocal, and bilateral. Such clinical presentations make bilateral mastectomy the only way to ensure removal of all of the LCIS present, an approach that is drastic for a risk factor lesion unless there are other compelling confounding breast cancer risk factors present. Finally, the biologic behavior of pleomorphic LCIS remains controversial in terms of long-term outcomes and risk of invasive cancer development.

Keywords

lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), pleomorphic LCIS, breast cancer risk factor, core biopsy, excisional biopsy, chemoprevention

Lobular neoplasia is the overarching nomenclature used to describe the spectrum of proliferative but noninfiltrative changes seen within the lobular units of the breast. Lobular neoplastic lesions include atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), each of which is associated with an increased risk of developing a subsequent invasive breast cancer (IBC). Pathologically, lobular neoplasia is diagnosed when the acini of the terminal duct lobular units are filled and distended by small, uniform, loosely cohesive cells. The distinction between ALH and LCIS has historically been based on the degree of histologic change observed by the pathologist. At the cellular and proteinomic levels, ALH and LCIS have striking similarities to invasive lobular cancers (ILC) with most staining positive for estrogen receptors (ERs), having low proliferative index rates, and being ErbB2 (HER2/neu) negative.

Although recognized since the 1940s as a unique histopathologic finding, controversy remains regarding both the clinical significance and overall invasive malignant potential of LCIS. LCIS is a marker for the development of invasive carcinoma, but the location for that subsequent cancer is not confined to the site at which LCIS was found. Actually, LCIS is a significant breast cancer risk factor for subsequent cancer in both breasts and with either ductal or lobular histology. Analogous to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and invasive ductal carcinoma, genetic evidence suggests that LCIS can be a nonobligatory precursor of ILC. However, the frequency with which malignant progression from LCIS to ILC actually occurs remains an area of vigorous debate. From a diagnostic perspective, management dilemmas continue as to whether LCIS requires surgical excision when it is seen on percutaneous needle sampling or if there are cases in which no further workup beyond needle biopsy is required. At the opposite extreme, there is debate if some LCIS cases should be removed with negative surgical margins after open surgical biopsy for therapeutic purposes, which then begs the question of whether radiation therapy should be offered to these potentially more aggressive cases. Although treatment strategies have evolved from routine mastectomy to surveillance since LCIS was first described, some in the medical community continue to question whether more aggressive intervention should occur in selected LCIS cases.

The purposes of this chapter are to define the historical background that led to our current understanding of LCIS biology, delineate histopathologic features of classic and “pleomorphic” LCIS, discuss the clinical presentation and natural history of LCIS, examine the evidence for and against routine surgical excision after the diagnosis of LCIS on image-guided sampling, review the role for chemoprevention in LCIS management, and discuss the role of surgical prophylaxis for LCIS in the small subgroup of patients for whom it may be appropriate.

Historical Background

LCIS as a Premalignant Lesion

Lobular neoplasia was initially described in 1941 when Foote and Stewart published their classic report of LCIS. At that time, LCIS was generally seen in conjunction with ILC, as illustrated in Godwin’s 1952 case report in which he describes it as a premalignant lesion. Because LCIS was believed to be an obligate precursor to invasive cancer, mastectomy was initially recommended as an appropriate therapeutic procedure after its histologic diagnosis on breast biopsy, and this remained the standard of care for the next 40 years. Today we recognize the selection bias from that period before mammographic screening when all breast cancers were diagnosed as clinically detected findings such as palpable masses. In today’s era of mammographic imaging and needle biopsy, we are now able to examine lobular neoplasia in isolation and recognize that early reports greatly exaggerated its malignant potential ( Table 38.1 ).

| 1865 | Cornil | Described intraepithelial breast carcinoma in lobules |

| 1919 | Ewing | Published photomicrographs of LCIS |

| 1931 | Cheatle and Cutler | Challenged whether malignant-appearing cells confined to lobules/ducts were “precancerous” |

| 1941 | Foote and Stewart | Coined term lobular carcinoma in situ |

| 1950s | LCIS generally seen together with invasive cancer, assumed to be premalignant hazard | |

| 1952 | Godwin | Suggested that LCIS evolves into ILC; recommended mastectomy for treatment |

| 1978 | Haagensen et al. | Defined lobular neoplasia (ALH and LCIS) as fundamentally benign |

| 1980s | LCIS shifts to being identified as a risk factor for invasive cancer | |

| 1996 | Frost et al. | Describes pleomorphic LCIS |

| 2000 | Middleton et al. | Proposes relationship between pleomorphic LCIS and pleomorphic ILC |

LCIS as a Risk Factor for Invasive Breast Cancer and Lobular Neoplasia

In the late 1970s the dominant belief that LCIS required therapeutic mastectomy was questioned when Haagensen at Columbia and Rosen at Memorial Sloan-Kettering both independently began to advocate for less drastic management. In Haagensen’s series, 211 women with pure LCIS underwent excision alone and were followed for evidence of development of subsequent IBC. Of the women, 10% developed an ipsilateral breast cancer, and 9% were subsequently diagnosed with a contralateral invasive tumor. When occurring in the same breast, the invasive cancers were not always found at the original LCIS biopsy site. Haagensen argued that LCIS is better described as a risk factor than a preinvasive cancer because longitudinal series show IBC of either ductal or lobular histology developing in either breast with similar frequency. As a risk marker for cancer, bilateral mastectomy was felt to be overly aggressive and largely unnecessary in the setting of LCIS.

To dissuade surgeons from managing LCIS as a malignant lesion warranting mastectomy, Haagensen and colleagues recommended reclassifying LCIS as lobular neoplasia , thus eliminating the word carcinoma from the name and removing any distinction between ALH and LCIS. They reasoned that avoiding mastectomy was appropriate because of both the low incidence of subsequent breast cancer observed and the nearly equal hazard of contralateral breast cancer, which would be left unaddressed by a unilateral mastectomy. In a 21-year follow-up study of Haagensen and colleagues’ original patients, among the 99 patients available for follow-up, 24% developed either DCIS or IBC, far lower than the rates that would be expected with an obligate precursor malignant lesion. Observation in place of mastectomy was gradually accepted as adequate management for lobular neoplasia, leading ultimately in the 1990s to the abandonment of routine mastectomy after an LCIS diagnosis.

Continued Definition of LCIS as a Unique Stage 0 Preinvasive “Cancer”

Despite a growing body of supportive evidence, there still exists some resistance to the hypothesis that lobular neoplasia represents a single pathologic entity of limited malignant potential. Several large professional entities, including the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Program (NSABP) and the American Joint Commission on Cancer, have continued to classify LCIS as a Stage 0 lesion at this time, although significant discussion regarding whether this should be the case is underway and this designation may change. Despite this classification, there is agreement that observation rather than mastectomy is now the preferred course of treatment when lobular neoplasia is diagnosed. LCIS similarly continues to be included in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Breast Cancer Guidelines, although specific cancer management is not recommended if the classic form of LCIS alone is identified at biopsy. Inclusion in cancer guideline documents is unfortunate because it can perpetuate concern among women diagnosed with LCIS and stimulate fear that they too have breast cancer, when they fundamentally do not.

LCIS Histopathology

Morphologic Features of LCIS

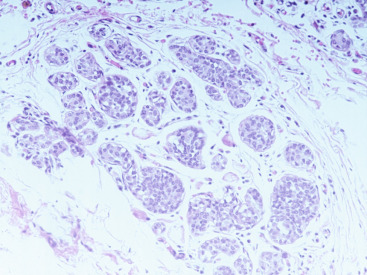

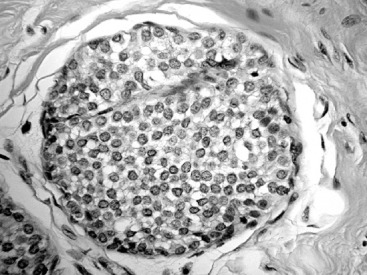

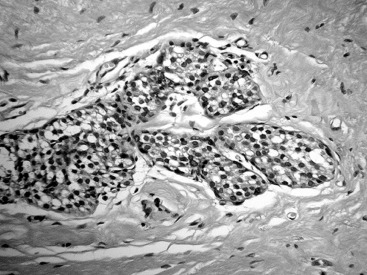

The histologic distinction between lobular and ductal neoplastic processes was initially based on location in the ductal-lobular system and differences in cytologic characteristics. In their original 1941 description, Foote and Stewart described LCIS as a proliferation of small, uniform, discohesive cells filling and often distending the acinar units within a lobule. In this classic form of LCIS, the nuclei are round, have indistinct nucleoli, uniform chromatin and a distinctly monotonous, low-grade appearance with minimal mitotic activity ( Fig. 38.1 ). The lobular-based proliferation of LCIS is typically solid, without the architectural lumen formation typical of cribriform pattern DCIS. Lobular proliferations that fill and distend at least 50% of the acini in a lobule are classified as LCIS, whereas involvement of less than 50% of the acini is considered ALH ( Fig. 38.2 ). Because this definition of lobular distention can be subjective and the 50% threshold is somewhat arbitrary, some pathologists prefer the all-encompassing term lobular neoplasia, whereas others favor the separate terminology, arguing that it remains clinically useful because LCIS conveys a higher IBC risk than does ALH. Page and colleagues estimated that ALH conveys a four- to fivefold increased invasive cancer risk, whereas LCIS conveys a full ninefold increased risk in the absence of endocrine suppression.

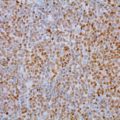

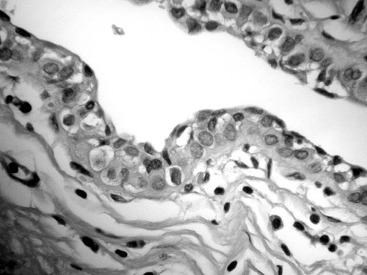

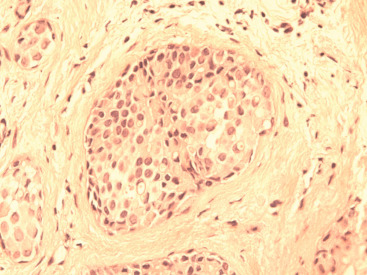

LCIS frequently extends beyond the lobules to involve the ductal system. This pattern of spread has a Pagetoid appearance, meaning that the neoplastic cells infiltrate from the lobule down into the adjacent duct, separating the basement membrane from the overlying epithelium, displacing and often attenuating the normal ductal epithelial layer ( Fig. 38.3 ). As with other etiologies, there can be significant variation in the degree and extent to which LCIS involves the breast. Uncommonly, classic LCIS will appear especially florid, with markedly distended lobules and foci of necrosis. These cases can be difficult to distinguish from DCIS, which more classically contains this type of central necrosis. Expression of the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin (E-cadherin) is typically lost in LCIS and retained in DCIS, making the use of immunohistochemistry staining for this marker useful in this differential ( Fig. 38.4 ).

Pleomorphic LCIS

There have been multiple descriptions of LCIS showing an in situ lobular pattern of growth similar to the classic LCIS form (see Fig. 38.1 ) but a high-grade, pleomorphic cytology that more resembles the aggressive phenotype of high-grade DCIS. Such lesions have been variably called pleomorphic LCIS ( Fig. 38.5 ). In contrast to the monomorphic cells of classic LCIS, pleomorphic LCIS cells have marked nuclear atypia, demonstrate variation in size and have frequent to abundant mitotic activity. The pleomorphic form of LCIS more frequently contains central comedo necrosis, making its appearance strikingly similar to comedo-type high-grade DCIS. In the past, pleomorphic LCIS was commonly diagnosed as high-grade DCIS by pathologists who were concerned that the high-grade cytology represented an aggressive in situ process that should be managed as such. A molecular factor that distinguishes lobular from ductal pathology is the expression of E-cadherin, a cellular adherence protein that is present in ductal pathology but is absent in lobular disease. The development of an immunohistochemical test for E-cadherin helped standardize pathology interpretation and is now a standard discriminating test when the in situ morphology is unclear or ambiguous. Histologic clues to this diagnosis include finding a discohesive appearance within a solid, high-grade in situ lesion, the presence of intracytoplasmic lumens or the coexistence of classic LCIS. E-cadherin staining is often required for confirmation that the cells are lobular in origin. It has been speculated that pleomorphic LCIS may have an increased likelihood of being associated with ILC and, in particular, its pleomorphic subtype that is among invasive cancers known to be more biologically aggressive.

Immunohistologic Features and Molecular Genetics of LCIS

Most often, classic LCIS is strongly positive for ER expression and, in keeping with its low-grade biology, rarely demonstrates HER2 overexpression or p53 alterations. This behavior contrasts with pleomorphic LCIS, which typically has lower levels of ER expression and can be positive for HER2 overexpression or contain p53 alterations, factors that all suggest a more aggressive behavior at the cellular level. Molecular analysis of pleomorphic LCIS suggests that although it is highly likely to contain some of the same molecular alterations seen in classic LCIS (such as 1q gains and 16q losses), it frequently has accumulated additional alterations that are more typical of high-grade ductal carcinomas.

Clinical Presentation, Natural History, and Biologic Significance of LCIS

Clinical Features of LCIS

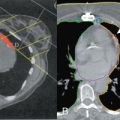

LCIS typically presents as an asymptomatic, occult lesion incidentally discovered during histologic workup for another clinical or radiographic indication. Only rarely will LCIS present as a discrete lesion seen either by mammogram or ultrasound. It is even less common for lobular neoplasia to present as a clinically palpable mass. Most instances of LCIS are incidentally discovered on breast biopsy conducted for another reason. Although fewer than 5% of breast biopsies performed for benign conditions ultimately yield a diagnosis of LCIS, it is hypothesized that the true incidence may be much higher in the general female population because a large number of women with lobular neoplasia remain undiagnosed as they have no other indication for breast biopsy.

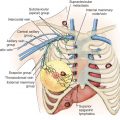

LCIS is commonly widespread in the breast, with patterns that are multifocal, multicentric, and/or bilateral. Early publications detailed its multifocal nature, noting that when patients underwent mastectomy after surgical biopsy showing LCIS, the breast specimen commonly had residual disease in areas outside the biopsy cavity, with a diffuse speckled, microscopic distribution through multiple lobules of a given region. Rosen and colleagues observed that LCIS was commonly multicentric, being present in multiple quadrants of the breast in 24 of 50 (48%) mastectomy specimens. Beute and colleagues found that among 119 patients diagnosed with LCIS between 1974 and 1987 in their institution, 82 had both breasts sampled either by mirror-image biopsy or contralateral mastectomy. Of these, LCIS was found to be bilateral in half (41/82) of the patients.

Risk of Subsequent Invasive Carcinoma After LCIS Diagnosis

Women diagnosed with LCIS are typically quoted to have an 8- to 10-fold increased lifetime risk for developing breast cancer in both the ipsilateral and the contralateral breast. The absolute risk of breast cancer after LCIS is 20% to 25% after 20 years. Mathematical modeling suggests that during the first 15 years after biopsy, women with LCIS have 10.8 times the risk of breast cancer development compared with women of comparable age who lack proliferative disease findings on breast biopsy. A more recent publication from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center examining 29 years of clinical surveillance reported a 15.8% rate of subsequent breast cancer development among 1060 women diagnosed previously with LCIS. The majority of the cancers were ipsilateral (63%), with 25% contralateral and 12% bilateral with both ductal and lobular invasive histology. Chemoprevention was the only factor found on multivariate analysis to influence breast cancer risk, substantially decreasing it. On average, they found a 2% annual incidence of breast cancer development in the setting of a prior diagnosis of LCIS.

In general, the risks of cancer in the ipsilateral and the contralateral breast are approximately equal, as shown in multiple longitudinal studies of patients diagnosed with LCIS by surgical biopsy ( Table 38.2 ). These studies illustrate the primary reason that LCIS is not typically treated surgically with lumpectomy: the only logical operation would be a bilateral mastectomy, which would be unnecessary approximately 80% of the time. It is possible that some subgroups of LCIS may exhibit a more aggressive unilateral biology and preinvasive behavior. The extent of LCIS (few lobules vs. extensive disease) and subtyping based on classic versus pleomorphic histopathology has not always been a standard part of pathology reports. As a result, retrospective analysis of population-based data is challenging, and additional prospective data are necessary to answer this question. Rendi and colleagues attempted to provide more clarity on whether the amount of LCIS seen at core needle sampling had any correlation with the risk of identifying subsequent invasive disease. In their study of 106 patients with pure lobular neoplasia diagnosed on core sampling, they found that among the 33 patients with pure LCIS, the upgrade rate at excision for malignancy was 4.4% and only occurred when extensive (more than four foci) of LCIS was present initially. Such findings have allowed the NCCN screening and diagnosis panel to suggest that for individuals with classic LCIS on core sampling where the finding is concordant with breast imaging findings, surveillance alone is sufficient and surgical excision may not be necessary for definitive diagnosis.

| Haagensen, 1986 | |

| Mean follow-up, years | 14.7 |

| Ipsilateral cancer | 11% |

| Contralateral cancer | 27/258 (10%) |

| Anderson, 1974 | |

| Mean follow-up, years | 15 |

| Ipsilateral cancer | 20% |

| Contralateral cancer | 17% |

| Wheeler et al., 1974 | |

| Mean follow-up, years | 15.7 |

| Ipsilateral cancer | 4% |

| Contralateral cancer | 15% |

| Page et al., 1991 | |

| Mean follow-up, years | 19 |

| Ipsilateral cancer | 15% |

| Contralateral cancer | 10% |

| Rosen et al., 1978 | |

| Mean follow-up, years | 24 |

| Ipsilateral cancer | 22% |

| Contralateral cancer | 20% |

| King et al., 2015 | |

| Mean follow-up, years | 29 |

| Ipsilateral cancer | 10% |

| Contralateral cancer | 5% |

Female Steroid Hormones and LCIS

Changing Incidence Rates of LCIS and the Influence or Exogenous Hormones on Lobular Carcinogenesis

The incidence rates of ILC increased steadily from 1977 to 1999, whereas the incidence rates of IDC increased at a similar rate until 1987 and then leveled off until 1999. Since 1999, however, rates of both ILC and IDC have declined by approximately 4% per year. LCIS incidence rates increased in parallel with ILC rates from 1977 to 1999, although rates of LCIS held steady from 1999 to 2006, despite a decline in ILC during that same time period. On the basis of available SEER data from the United States, LCIS rates are highest among women aged 50 to 69 years, but although diagnosis of LCIS increased up until 2006 for women aged 30 to 49 and aged 70 years or older, rates fell after 2002 among women 50 to 69 years of age. In contrast, ILC rates remain highest among women 70 years of age or older, with declines in ILC cases since 2002 among both 50- to 69-year-old women and those aged 70 years and older. ILC rates among women 30 to 49 years of age have increased slowly over the past 30 years but remain much lower than the rates seen among women 50 years of age and older.

Rising rates of all lobular pathology through 2002, as well as their subsequent fall, may be related to changing patterns of combined estrogen and progestin menopausal hormone therapy (CHT) use. Although it is established that CHT use increases breast cancer risk, almost all studies that have reported on associations between CHT and risk of ILC versus IDC indicate that this association varies by histologic type. In these studies, CHT use is associated with 2.0- to 3.9-fold increases in ILC risk, but has much less of an impact on IDC risk. The publication of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial results of CHT use in 2002, which demonstrated that the risks of long-term CHT use (for >5 years) outweighed its benefits, resulted in a dramatic decline in the use of CHT among women worldwide. It has been hypothesized that abrupt cessation in CHT use is at least partially responsible for the decline in total breast cancer rates after 2002 observed in the United States and may account for the drop in ILC and LCIS incidence rates since 2002 primarily among women most likely to be CHT users, those 50 to 69 years of age. Despite this reasonable hypothesis, others have argued that saturation of screening, and not a decrease in CHT use, may be a greater contributor to the decline in overall breast malignancy rates demonstrated since 2002. Interestingly, a more recent SEER database study suggests that the rate of LCIS increased from 2.00 in 100,000 patients in 2000 to 2.75 in 100,000 patients in 2009.

In general, lobules become atrophic and tend to disappear after menopause unless the patient is taking hormone therapy. Despite this finding, Wellings and colleagues reported that some human mammary lobules persist after menopause and certain atypical lobules are morphologically similar to preneoplastic alveolar nodules that occur in strains of mice with a propensity for developing mammary carcinoma. They suggest that these persistent atypical mammary lobules could be precancerous in human beings. These findings might help explain why ILC rates are highest among women 70 years of age and older.

Not all cases of LCIS are diagnosed in the postmenopausal setting. A recent publication by McEvoy and colleagues identified 58 women with atypical breast lesions, including eight with pure LCIS, diagnosed under age 35 years. At median follow-up of 86 months, seven of the cohort had developed breast cancer, with four among those initially found to have LCIS, two whose initial lesion was ALH and one whose initial lesion was atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH). There were four ipsilateral cancers, including three initially diagnosed with LCIS and three contralateral cancers ultimately identified at a mean age of 41 years. These authors concluded that young women with atypical lesions were at a strikingly high risk of developing breast cancer and advocated for close clinical surveillance and follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree