12 Limited Resection: Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes of Transanal Excision and Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery

Introduction

Total mesorectal excision is the standard operation for rectal cancer. In this procedure referred to as radical resection in this chapter, the rectum is excised together with the mesorectum, which contains lymphatic tissue draining the rectum.1 More proximal rectal tumors (upper and mid rectum) can be removed by an anterior resection of the rectum with sphincter preservation. However, very distal rectal tumors may require an abdominal perineal resection with permanent colostomy to achieve a wide excision of the tumor. Patients who undergo radical resection of stage I rectal cancers can expect excellent long-term results (4.5% 5-year local recurrence rate and 90% 5-year disease-free survival rate).2 However, anterior and abdominal perineal resections of the rectum constitute major abdominal surgery and thus carry risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality including anastomotic leak, which could require re-operation; injury to pelvic nerves leading to sexual and/or urinary dysfunction; and the chance of suboptimal long-term bowel function (clustering of bowel movements and incomplete evacuation). Local excision of the tumor is an attractive alternative to radical resection for early rectal cancer because (1) it is a more straightforward surgical procedure, (2) it preserves bowel function, and (3) it carries less risk of perioperative morbidity. Nevertheless, the role of local excision in the treatment of rectal cancer continues to be debated. During the past 10 years, a series of retrospective studies has reported higher than expected rates of pelvic recurrences after local excision of rectal tumors.2–5 There is concern about the adequacy of the local excision as a cancer operation because the procedure addresses only the primary tumor and does not assess for lymphatic spread by removing the regional lymph nodes. In addition, because of the nature of the procedure, locally excised rectal tumors frequently have closer margins and are more prone to spillage of tumor cells into the surgical field. Thus, at this time, local excision is best suited for selected early rectal cancer (T1N0)—tumors associated with a low risk of lymphatic spread.

Local excision is sometimes used to treat patients with more advanced tumors (T2 and T3), but these patients generally have medical comorbidities that make radical excision risky, or they adamantly desire sphincter preservation for very low rectal cancers. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy treatments continue to improve, and this has prompted interest in using local excision combined with concurrent neoadjuvant chemoradiation to treat certain T2 rectal cancer. At this time, local excision of T2 tumors should be considered only in the setting of a clinical trial.

Long-term Outcomes After Local Excision

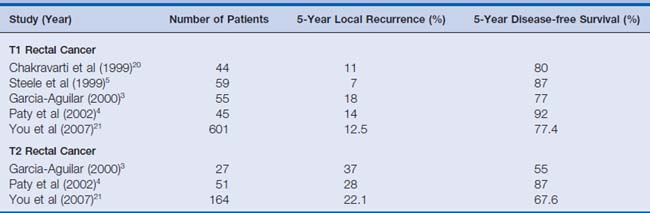

The procedure of local excision gained momentum after Morson and colleagues6 (1977) reported that radical resection and local excision have similar oncologic results. During the past decade a number of centers have retrospectively reviewed their results with local excision for rectal cancer and discovered higher than anticipated rates of local recurrence and lower than anticipated rates of long-term survival (Table 12-1). Although the studies have been limited by the sample size and heterogeneity of the study population, by variable preoperative staging strategies, and by disparate surgical technique, the results have curbed some of the enthusiasm for local excision. To date, there has been no prospective comparison of local excision and radical resection for early rectal cancer. However, in the retrospective studies comparing local excision with radical resection, local excision of T1 and T2 rectal cancer is found to be associated with higher rates of pelvic recurrences, At this time, however, it is not clear whether this ultimately influences 5-year survival rates. Based on retrospective studies with variable follow-up of T1 and T2 cancers, local recurrence rates range from 7% to 18% and from 13% to 37%. In T1 and T2 cancers, disease-free survival rates range from 77% to 93% and from 63% to 87%, respectively.

Patient Selection

First, digital examination is used to determine the mobility of the tumor, the distance from the anal verge, and the strength of the internal and external anal sphincter. An immobile, fixed tumor predicts invasion through the bowel wall. After digital examination, the proctoscope is inserted to document the tumor size and distance from the dentate line. This determines whether local excision is technically feasible. Tumors best suited for local excision are smaller than 4 cm in diameter and involve less than 40% of the rectal wall. Distance from the anal verge is important for determining whether transanal techniques are adequate for resection or whether transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) excision should be considered. Proximal tumors can be challenging to excise through the transanal approach. Frequently, radical resection can be accomplished with sphincter preservation in these proximal cancers, and thus the benefits of local excision may not outweigh the increased risk of local recurrence after local excision. General criteria for local excision are listed in Box 12-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree