Leptomeningeal Metastasis

Eli L. Diamond

Lisa M. DeAngelis

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) occurs when tumor spreads to the subarachnoid space and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surround the brain and spinal cord. It may be the sole site of central nervous system (CNS) metastasis or may coexist with brain, dural, or parenchymal spinal cord metastases. LM is an increasingly important neurologic complication of solid tumors in addition to its well-recognized association with hematopoietic malignancies. Enhanced clinical detection with improved neuroimaging and prolonged patient survival with better control of systemic cancer contribute to the increased frequency of LM in patients with solid tumors, particularly breast cancer (1).

The frequency of LM in clinical series of patients with breast cancer is estimated at 8%; however, autopsy series of these patients reveal an incidence of 3% to 40% (2). LM usually coexists with disseminated systemic disease, but it can also occur as an isolated site of relapse. The CNS may be a sanctuary site for metastatic disease in patients with breast cancer whose systemic tumor has been controlled with effective systemic therapies (3), particularly HER2-positive breast cancer treated with trastuzumab (4). The repertoire of active agents to treat breast cancer consists mainly of water-soluble drugs that do not penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB). There are numerous efflux transporters that comprise the BBB, including P-glycoprotein, other multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP), and the breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) that extrudes chemotherapeutic agents such as anthracyclines, taxanes, and vinca alkaloids (5). These agents can eradicate disease in systemic sites, but if a microscopic tumor resides in the CNS, they do not cross the intact BBB; thus, these agents allow the CNS tumor to grow, leading to subsequent brain or leptomeningeal metastases. Once a CNS tumor reaches a macroscopic size, the BBB is typically disrupted and, occasionally, systemically administered drugs can be effective against CNS metastases. However, sequestration of a microscopic tumor behind an intact BBB is likely a major explanation for the rising frequency of brain and leptomeningeal metastases in patients with otherwise well-controlled breast cancer.

Determining the diagnosis of LM is often difficult because the presenting neurologic symptoms can be confused with other CNS complications of breast cancer. Neuroimaging and laboratory tests aid in establishing the diagnosis but are limited by a lack of sensitivity, specificity, or both. Optimal therapy has not been defined; difficulties of drug distribution in the CSF, intrinsic drug resistance of the metastases, and neurotoxicity are important factors that limit the success of standard therapies. Nevertheless, in some patients, an aggressive approach is rewarding, and prolonged control of both disease and symptoms is possible. This chapter reviews the clinical presentation of this disorder, the methods of diagnosis, and the recommended therapeutic approaches.

CLINICAL SETTING

CNS metastases in breast cancer have been associated with younger age, premenopausal status, infiltrating ductal histology, estrogen- and progesterone-receptor negativity, aneuploidy, altered p53, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) overexpression (6). Lobular type breast cancer has a predilection for LM compared to other histologic types of breast cancer, with one autopsy study showing LM to occur in 14% of all cases of lobular carcinoma (2). In a study done by Altundag et al. (7), 3.8% of 420 breast cancer patients with CNS metastases had a tumor of lobular histologic type, but 31.6% of these patients presented with isolated LM, compared to 7% of all patients in the series. Studies have shown an increased incidence of CNS metastases in women with HER2-positive breast cancer as high as 25% to 40% (8). This increase may be multifactorial and includes biologic factors as well as treatment-related factors. The use of trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody directed against the HER2 receptor, is associated with increased systemic response rates, prolonged disease-free survival, and overall survival for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer. Due to its high molecular weight, it does not cross the BBB, which may explain the emergence of CNS metastases. It has been postulated, however, that trastuzumab does not increase the risk of CNS relapse directly but rather improves systemic control and overall survival, leading to

an unmasking of occult brain metastases that would otherwise remain clinically silent (9). In fact, other studies do not support a direct association between treatment with trastuzumab and increased CNS metastases (10). One study observed a lower rate of LM in patients with brain metastases and HER2-positive disease compared to HER2-negative patients with brain metastases (11).

an unmasking of occult brain metastases that would otherwise remain clinically silent (9). In fact, other studies do not support a direct association between treatment with trastuzumab and increased CNS metastases (10). One study observed a lower rate of LM in patients with brain metastases and HER2-positive disease compared to HER2-negative patients with brain metastases (11).

A wide time interval between the diagnosis of breast cancer and the occurrence of LM has been reported; in large series, it ranges from a few weeks to more than 15 years (2). In rare instances, LM is the initial manifestation of breast cancer. Many patients with a solid tumor have widespread metastatic disease when LM is diagnosed but, in patients with breast cancer, the systemic tumor may be inactive or responding to chemotherapy. Of 48 patients diagnosed with LM reported by de Azevedo et al. (1), 34 (56.7%) had been treated with 3 or more chemotherapy regimens prior to the diagnosis of LM, and 51 (85%) had metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

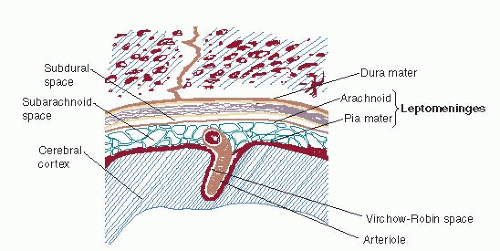

The cerebral and spinal meninges are composed of the dura mater, arachnoid, and pia mater. The leptomeninges include the arachnoid and pia mater. The pia mater is a thin lining, closely adherent to the surface of the brain and spinal cord, separated from the arachnoid by fine trabeculae. It follows the sulci of the cerebral cortex and penetrates the parenchyma of the CNS in association with arterioles. The associated parenchymal perivascular space is termed the Virchow-Robin space (Fig. 78-1). Pathologic evidence suggests several methods by which tumor cells reach the leptomeninges:

Hematogenous spread to the vessels of the arachnoid or to the choroid plexus of the ventricles (the latter produces dissemination of malignant cells to the leptomeninges by normal CSF flow);

Direct extension from adjacent metastasis in the cerebral parenchyma or dura or the lymphatic paraspinal region;

Retrograde access to the subarachnoid space by tumor cells infiltrating the venous system from adjacent calvarial or spinal metastases; or

Iatrogenic spread after resection of a brain metastasis.

Tumor dissemination into the CSF after surgical procedures is primarily associated with removal of metastases from the cerebellum, in which the subsequent development of leptomeningeal disease may be as high as 67% (2). The risk of LM after posterior fossa surgery is increased in the setting of piecemeal as opposed to en bloc resection. There does not seem to be a relationship between radiosurgery of a cerebellar metastasis and the development of LM (12).

Autopsy studies demonstrate that leptomeningeal tumor grows in a sheet-like fashion along the surface of the brain, spinal cord, cranial nerves, and nerve roots (2). It usually disseminates widely, but it may be limited to portions of the cerebral or spinal leptomeninges. When tumor cells are closely adherent to one another, multifocal nodules may form, particularly on the cauda equina or ventricular surface of the brain. LM is usually accompanied by a fibroblastic proliferation of the meninges. An inflammatory response may be seen pathologically in the leptomeninges and, occasionally, reactive lymphocytes accompany malignant cells in a CSF specimen. Tumor may ensheathe meningeal arteries and veins within the subarachnoid space and may extend into the Virchow-Robin spaces, with resulting perivascular tumor cuffing and parenchymal invasion; tumor cells may invade into the cranial nerves and spinal roots as well. Invasion may interfere with blood supply to neurons, causing ischemic changes and even frank infarction (2). Neuronal dysfunction may also be caused by local metabolic derangement because of competition between tumor cells and neurons for glucose and other critical nutrients.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical hallmark of LM is the simultaneous occurrence of multifocal abnormalities at more than one level of the neuraxis (cerebral, cranial nerve, and spinal). A careful neurologic examination often reveals more signs than suggested by the clinical symptoms. Spinal symptoms are the most common presentation of LM (Table 78-1); limb weakness is frequent, usually involving the legs, and may be accompanied by paresthesias and pain in the affected limb. Neurologic examination may reveal asymmetric depression of deep-tendon reflexes, radicular limb weakness, and sensory loss. Signs of meningeal irritation, such as nuchal rigidity, are rare. The most common finding of cerebral dysfunction is a change in mentation. Seizures occur in fewer

than 10% of patients. Cerebral symptoms of LM often result from the obstruction of CSF flow and include headache, changes in mentation (lethargy, confusion, and memory loss), nausea and vomiting, and ataxia. These symptoms often indicate elevated intracranial pressure, which may occur with or without hydrocephalus. The most common cranial nerve symptom is diplopia. Hearing loss, visual loss, and facial numbness also occur. Paresis of the extraocular muscles is the most common cranial nerve abnormality, followed by facial weakness and diminished hearing (2).

than 10% of patients. Cerebral symptoms of LM often result from the obstruction of CSF flow and include headache, changes in mentation (lethargy, confusion, and memory loss), nausea and vomiting, and ataxia. These symptoms often indicate elevated intracranial pressure, which may occur with or without hydrocephalus. The most common cranial nerve symptom is diplopia. Hearing loss, visual loss, and facial numbness also occur. Paresis of the extraocular muscles is the most common cranial nerve abnormality, followed by facial weakness and diminished hearing (2).

TABLE 78-1 Presenting Symptoms and Signs of Leptomeningeal Metastases | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

METHODS OF DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of LM often requires a high index of suspicion. Initial testing may not reveal the diagnosis, and the physician must often resort to a variety of tests combined with clinical findings to establish the diagnosis. Occasionally, a presumptive diagnosis is made and treatment is initiated if the clinical picture is typical, other diagnoses are excluded, and the CSF is abnormal despite a negative CSF cytologic examination (Table 78-2).

Neuroimaging with gadolinium-enhanced MRI should be the first test obtained for a patient with cancer who has new neurologic symptoms. Specific findings on MRI may be sufficient to establish the diagnosis of LM and may eliminate the need for CSF analysis. Neuroimaging is also essential to exclude parenchymal brain (Chapter 76) or spinal epidural lesions (Chapter 77), which may produce a similar clinical picture and may coexist with LM. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI is the best technique for either cranial or spinal imaging. Definitive imaging findings that establish the diagnosis of LM include:

Enhancement of the leptomeninges over the convexities or within the cerebral or cerebellar sulci;

Tumor nodules or diffuse enhancement of the brainstem, spinal cord, or cauda equina (Figs. 78-2, 78-3 and 78-4);

Enhancement of the cranial nerves; and

Enhancement of the basal cisterns or subependymal area.

Despite the sensitivity of MRI, it is negative in 33% of patients with positive CSF cytology, but it is negative in only

10% to 25% of patients with solid tumors compared with 48% to 55% of patients with hematologic malignancies (2, 13). The radiologic diagnosis of LM may be missed in a patient receiving bevacizumab because of diminution of post-gadolinium enhancement (14). Rarely. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) CT may establish a diagnosis of LM (15).

10% to 25% of patients with solid tumors compared with 48% to 55% of patients with hematologic malignancies (2, 13). The radiologic diagnosis of LM may be missed in a patient receiving bevacizumab because of diminution of post-gadolinium enhancement (14). Rarely. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) CT may establish a diagnosis of LM (15).

TABLE 78-2 Diagnosis of Leptomeningeal Metastases | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree