31

Introduction to Geriatric Oncology

Stuart M. Lichtman

INTRODUCTION

Age is the single most important risk factor for developing cancer, with 60% of all newly diagnosed malignant tumors and 70% of all cancer deaths occurring in persons 65 years or older. It has been estimated that by the year 2030, 20% of the U.S. population (70 million people) will be older than age 65 years. The median age range for diagnosis for most major tumors is 68 to 74 years, and the median age range at death is 70 to 79 years. The mortality rate is disproportionately higher for the elderly population. There are several potential reasons for this, including more aggressive biology, competing comorbidity, decreased physiologic reserve compromising the ability to tolerate therapy, physicians’ reluctance to provide aggressive therapy, and barriers in the elderly person’s access to care (1). The elderly patient with cancer often has an elderly caregiver, or is socially isolated. The older patients have not been participants in clinical trials and the data necessary to help clinicians care for these patients is lacking. All of these factors contribute to the difficulty of caring for these complex, heterogeneous, and vulnerable patients (2). The field of geriatric oncology has become increasingly recognized as an important component of cancer care and cancer research. This introductory chapter explores the major issues confronting clinicians, which are assessment and aging physiology.

GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT (GA) IN ONCOLOGY

The identification of problems in older patients is critical in prognostication and decision making. Researchers in geriatric oncology have demonstrated that the traditional method of routine history and physical is inadequate in determining elder-specific issues (3,4). Clinicians have not been trained to ask the appropriate questions and interpret the available data. Medical oncologists have used performance status scales such as the Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scales to help stratify patients for treatment and as part of clinical trial eligibility. This has been a valuable tool and, for the general oncology population, has been helpful and has withstood the test of time. However, this simple approach is not adequate in the complex, heterogeneous older population. These performance status scales often do not reflect the functional status of older patients (4). Clinicians will appropriately refer to published clinical trials and established national and international guidelines to assist in decision making and evaluating treatment options. 4Unfortunately, older patients have been grossly under represented in clinical trials, and data reporting has been inadequate (5,6). This includes registration trials for new drugs (7,8). When they do participate, they are an exceptional group of elders who have passed the often stringent eligibility requirements and usually have minimal to no comorbidity and an excellent performance and functional status. Therefore, the available data usually do not reflect the average patient seen in practice. The result is that there is a paucity of data with which to make true evidence-based decisions.

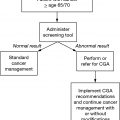

To obtain this important information, researchers in geriatric oncology have been developing GA scales appropriate for the oncology patient. There is a need to assess basic information. Functional assessments (see Chapter 13) include activities of daily living (toileting, feeding, dressing, grooming, ambulation, bathing) and instrumental activities of daily living (using the telephone, shopping, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, transportation, and ability to take medication accurately). Dependence in these areas has shown to be a prognostic factor for poor outcomes and treatment-related toxicity (9–11). The presence of geriatric syndromes (delirium, dementia, incontinence, falls, pressure ulcers, malnutrition, osteoporosis, hearing and vision difficulties, and sleep disorders) also has a negative impact (12). The study of the overall evaluation of the older patient has been an extrapolation of the established comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), an interdisciplinary diagnostic process focusing on the medical, psychosocial, and functional capabilities of the patient, in order to develop a coordinated and integrated plan for treatment and follow-up (13). It is recognized that a CGA as performed by geriatricians is not practical in the usual outpatient oncology setting. Researchers are trying to streamline the approach by determining the most important questions in terms of oncologic care and then validating this approach in various settings. A position paper published by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) highlighted the issues in this field and discussed the domains that needed to be evaluated and the important questions to be addressed (13).

There is a significant clinical rationale for performing GAs. A GA can provide relevant clinical information beyond that captured in a standard history and physical examination. It can help predict oncology treatment-related complications and overall survival. Data is emerging that it is helpful in making oncology treatment decisions. There are questions concerning what components of the GA should be incorporated in oncology-related assessments and how the problems which are detected can be addressed.

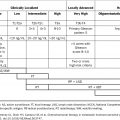

In terms of predictive models, one area that has developed a significant amount of important data is the risk of therapy-related toxicity. Two models have been developed and are described in detail in Chapter 13. The Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) score has been shown to be predictive for significant (grade 3+) hematologic toxicity (10). The power of this model is that it has been shown to be better than clinical judgment in predictive value. The study also demonstrated that those older patients with the lowest scores (0–3) still had a 25% risk of ≥ grade 3 toxicity. The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score is able to distinguish several risk levels of severe toxicity. It predicts separately hematologic and nonhematologic toxicity (14). Oncology-specific geriatric screening 5tools are also being developed to predict other outcomes (15,16) and are discussed in Chapter 14.

Another important consideration is recognizing frailty (see Chapter 14). The frail patient can be thought of an individual who has a higher susceptibility to adverse outcomes, such as mortality and institutionalization. From an oncology perspective, the “frail” label often indicates a patient who is dependent on others for basic activities and if given standard therapies will often not complete the treatment, have excessive toxicity, and therefore will not benefit. Clinicians need to recognize this group to avoid excessive toxicity and suffering (17,18). Predictors of mortality can be helpful to clinicians to weigh the risk versus benefits of therapy, particularly adjuvant treatment. The website e-prognosis (www.eprognosis.com) is one such example. Gait speed has been shown to be a powerful predictor of survival (19) and is clearly simple to evaluate. GA can also be helpful in predictions of delirium (11). These scales and predictive models have been shown not to be time-consuming to the medical staff, are often self-administered by the patient or can be done by nursing. Newer technologies are beginning to be utilized to capture and evaluate this information (20).

PHYSIOLOGY OF AGING AND DRUG THERAPY

A number of physiological changes accompany aging (21,22). Drug compliance is an important issue, particularly with the marked increase in oral anticancer therapies which compound the problem of polypharmacy (23–25). Studies have emphasized that obesity is a significant problem in the elderly population and should be considered in trials (26–28). Other variables to be considered are the effect of age and diet, and genetic polymorphisms (29). Polypharmacy can also affect metabolism due to the potential of drug–drug interactions. There is an age-related reduction in glomerular filtration rate which is not reflected by an increase in serum creatinine levels, because of the simultaneous loss of muscle mass that occurs with age. It should be noted that many older patients who have a serum creatinine in the normal range for a particular laboratory have renal insufficiency (30). Dosing recommendations for older patients and those with renal insufficiency have been published (22,31–35). Appropriate dose modifications can foster safe and effective outcomes (36). The study of the pharmacokinetics of chemotherapy in older patients has truly been lacking. Future study is required.

RESEARCH

Research in geriatric oncology is being performed by a growing number of investigators. The SIOG, founded in the year 2000, fosters the mission of developing health professionals in the field of geriatric oncology, in order to optimize treatment of older adults with cancer, through education, clinical practice, and research. The Society’s publication, the Journal of Geriatric Oncology, is the first journal devoted solely to the field. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (now the Alliance 6for Clinical Trials in Oncology) Cancer in the Elderly Committee has supported furthering research in geriatric oncology through clinical trials and secondary data analyses (37,38). The CARG initiated and supported trials in different clinical settings and, most importantly, mentors junior investigators in geriatric oncology and studies novel clinical trial designs (39). The Gynecologic Oncology Group Elderly (now NRG Oncology) task force is supporting the first prospective trial in older women with ovarian cancer and planning further studies in other diseases and modalities. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) also fosters a number of initiatives in geriatric oncology. These include a Geriatric Oncology Issue Exploration Team, educational materials including ASCO University, sessions at the annual meeting including a geriatric oncology track, the B. J. Kennedy Award for Excellence in Geriatric Oncology, articles in the ASCO Post, and a geriatric oncology component of the Cancer Education Committee. ASCO has also published a position paper encouraging research in older patients to increase the available evidence-based data (1). One area of great interest is rethinking clinical trial design. It is important that clinical trials prospectively obtain important patient data such as baseline functional status. Eligibility, appropriate endpoints, and toxicity evaluation should be reconsidered for older patients (40,41). Data analysis and clinical trial reporting also have to be adapted for appropriate evaluation and interpretation. These issues are imperative to obtain quality data so clinicians have the ability to make meaningful decisions.

The care of the older cancer patient is a complex endeavor. It requires careful thought and evaluation. Goals of therapy must be carefully considered. A multidisciplinary approach is preferred. Geriatric oncology ought to move to the forefront of oncology care. These vulnerable patients should be the focus of our endeavors.

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree