Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Although discussions of issues relating to surgical management of the large bowel frequently consider the colon and rectum as one entity, their associated standards of surgical care are quite dissimilar. This is most evident in the use of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) and the significantly different techniques required in the surgeons’ repertoire for rectal cancer management. In volume 1 of Operative Standards for Cancer Surgery, the discussion centered on the colon; in this section of volume 2, the focus of discussion topic is the rectum.

It is estimated that 39,910 rectal cancer cases will be diagnosed in the United States in 2017, 23,720 in men and 16,190 in women.1 Recent studies have also demonstrated a rising trend in the incidence of rectal adenocarcinoma among individuals <50 years of age. The optimal management for rectal cancer requires complete preoperative evaluation, an emphasis on strict adherence to oncologic surgical principles, and multimodality treatment for high-risk disease. However, there remains significant variation in rectal cancer practice, resulting in the potential for suboptimal outcomes.2

In Europe and elsewhere, initiatives aimed at reducing treatment variation and improving outcomes have demonstrated the value of the multidisciplinary team for these patients with rectal cancer.3,4,5,6 The amalgamation of appropriate preoperative imaging by using a rectal cancer protocol of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) combined with appropriate assignment of neoadjuvant therapy based on the MRI finding of a threatened circumferential resection margin has led to a more logical allocation of neoadjuvant therapy and an improvement in surgical ability to achieve tumor-free circumferential resection margins.7 Although the ultimate goal is to achieve tumor-free, long-term survival, the surrogate early markers include the ability of the surgeon to perform a complete or near-complete total mesorectal excision (TME), which in the vast majority of cases achieves tumor-free circumferential and distal resection margins. Numerous studies have shown that treatment standardization, including for surgical technique, at high-volume, multidisciplinary specialist centers (in Europe often referred to as “centers of excellence”) are able to achieve lower morbidity, lower mortality, shorter length of hospitalization, less resource utilization, and a lower rate of permanent stoma construction than nonspecialist centers with low volume.3,4,5,6 These same differences have been identified in the United States and have recently appeared in numerous publications.8

Founded in 2011 in the United States, the OSTRiCh (Optimizing the Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer) Consortium is a group of health care institutions that have come together with the purpose of improving the quality of rectal cancer care in the United States through advocacy, education, and research. Since May 2014, the OSTRiCh group has worked with the regents and officers of the American College of Surgeons to develop a rectal cancer accreditation program through the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer.9,10,11,12 Three separate quality-improvement initiatives for rectal cancer surgery are now under way. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons is constructing an educational skills module for TME. The College of American Pathologists is creating an educational skills module for pathologists, which will include synoptic reporting of rectal cancer specimens. A third and parallel initiative of the American College of Radiology is to develop an educational skills assessment module, including synoptic MRI reporting for radiologists.

Quality-improvement programs for rectal cancer should emphasize both the multidisciplinary principles for cancer care and the technical standards for surgery to ensure complete resection. Herein we describe the technical standards for the critical elements of rectal cancer surgery and highlight key areas for critical appraisal.

Anatomy

The proximal rectum is defined by the fusion of the taenia that typically occurs at the level of the sacral promontory. The distal boundary of the rectal reservoir, or ampulla, is the puborectalis ring, which is palpable as the anorectal ring on digital rectal examination. The mucosal lining of the rectum extends below the puborectalis ring into the functional anal canal to the dentate line that gives evidence that rectal cancer may occur within the functional (“surgical”) anal canal. The rectum is approximately 12 to 16 cm in length. It is covered by the peritoneum in front and on both sides in its upper third and only on the anterior wall in its middle third. The peritoneum is reflected laterally from the rectum to form the perirectal fossa and, anteriorly, the uterine or rectovesical fold. Depending on body habitus and sex, this fossa can be widely variable and may extend to the pelvic floor.

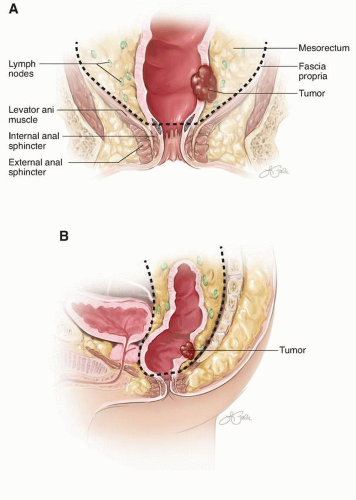

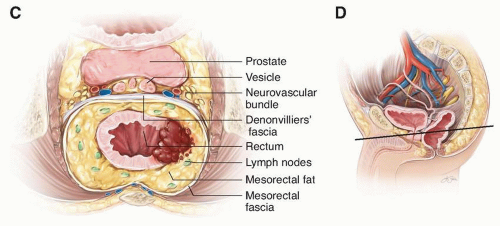

In general, the lower third of the rectum (the reservoir or ampulla) does not have a peritoneal covering. This extraperitoneal rectum is encircled by a variably thick, fatty sheath that contains perirectal lymph nodes and is enveloped circumferentially by the fascia propria. Separation extends posteriorly from the sacrum by Waldeyer’s fascia, from the pelvic sidewalls by the pelvic parietal fascia, and anteriorly from the prostate or vagina by Denonvilliers’ fascia. The mesorectum tapers distally so that no fatty sheath surrounds the rectal wall at the puborectalis sling (Fig. I-1).

Clinical and Pathological Staging

The TNM cancer staging system (by tumor, node, and metastasis) incorporates prognostic factors (clinically relevant, tumor-specific features that affect outcome) and predictive factors (features that forecast the likelihood of responding to particular treatments) and forms the basis of stage-directed treatment standards (Table I-1a, b, c and d).13,14 Clinical TNM staging is based on medical history, physical examination, imaging, and endoscopy with biopsy. Radiologic locoregional and systemic staging should occur prior to starting treatment. Currently, MRI and endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) are preferred for their accuracy in determining T and N status. ERUS may offer advantages in classifying early tumors (distinguishing T1 from T2 tumors and T2 from T3 tumors). MRI is generally preferred for the staging of more advanced T category tumors (substratification of T3 tumors based on the level of perirectal fat invasion, threatened mesorectal fascia, and perirectal vascular invasion). However, these distinctions are important only to the extent that they affect final management decisions.

For systemic staging, computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are usually sufficient. Radiologic examinations used to demonstrate the presence of extrarectal metastasis include chest radiography, CT, MRI, positron emission tomography, and positron emission tomography/CT scans. Clinical stage can then be assigned. Pathologic stage is assigned based on the resection specimen. Obtaining a preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level is recommended because it indicates the likelihood that subclinical or clinical liver or lung metastases are present.

In the event of recurrence or synchronous metastases, it is now recommended that the status of the genes KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF be evaluated and microsatellite instability (or mismatch repair) be assessed. The presence of metastatic disease is a major determinant of outcome and underlies the final management decision.

In the event of recurrence or synchronous metastases, it is now recommended that the status of the genes KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF be evaluated and microsatellite instability (or mismatch repair) be assessed. The presence of metastatic disease is a major determinant of outcome and underlies the final management decision.

FIGURE I-1 (continued) C: Axial view of the planes of the mesorectum. D: Sagittal view through pelvis. Solid line indicates level of axial view in C.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|