Proctectomy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Proximal Vascular Ligation

Total Mesorectal Excision

Lymph Node Dissection

Clearance of the Distal Margin

1. PROXIMAL VASCULAR LIGATION

Recommendation: Routine ligation of the inferior mesenteric vascular pedicle proximal to the origin of the left colic artery is generally unnecessary. Ligation of the superior rectal vascular pedicle just distal to the origin of the left colic artery is adequate. However, in the presence of clinical evidence for proximal inferior mesenteric artery lymph node involvement, the inferior mesenteric artery should be ligated at its origin for complete staging and for locoregional control of disease.

Type of Data: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of retrospective observational studies, and case series.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence.

Rationale

With the recognition that cancer cells spread through the lymphatic channels, early descriptions of surgery for rectal cancer indicated that ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) should be performed flush with the aorta. In 1908 Moynihan1 stated, “We have not yet sufficiently realized that the surgery of malignant disease is not the surgery of the organs; it is the anatomy of the lymphatic system.” The enthusiasm for resecting all lymph nodes along the IMA vascular pedicle has since been tempered by concerns about whether high ligation increases the risks of autonomic nerve

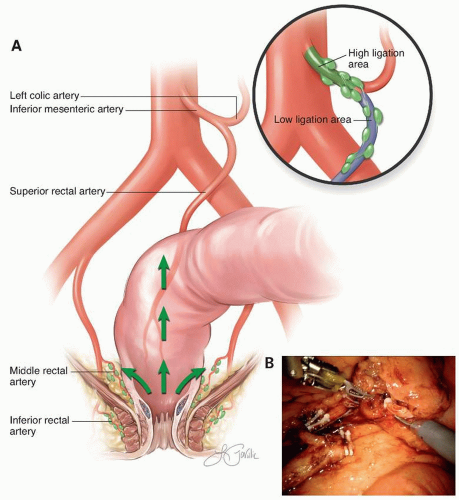

dysfunction and compromises the blood supply to the anastomosis. Ernest Miles,2 in his description of the abdominoperineal (APR) resection, recommended division of the IMA just distal to the left colic branch. Surgeons favoring this approach have opined that division of the IMA just distal to the takeoff of the left colic artery is adequate from an oncologic perspective and perhaps advantageous in preserving blood supply and avoiding autonomic nerve injury (Fig. 4-1).

dysfunction and compromises the blood supply to the anastomosis. Ernest Miles,2 in his description of the abdominoperineal (APR) resection, recommended division of the IMA just distal to the left colic branch. Surgeons favoring this approach have opined that division of the IMA just distal to the takeoff of the left colic artery is adequate from an oncologic perspective and perhaps advantageous in preserving blood supply and avoiding autonomic nerve injury (Fig. 4-1).

Numerous retrospective cohort studies have failed to find a consistent advantage of IMA division proximal (“high ligation”) relative to distal (“low ligation”) to the left colic artery. In 1984 Pezim and Nicholls,3 in a retrospective review, compared survival in 1,370 patients with rectosigmoid or rectal cancer who underwent either high or low ligation of the IMA. The authors found no difference in survival or complications between the two groups. Three retrospective studies from China and Japan, where high IMA ligation is considered the standard approach, reported low incidence of lymph node involvement proximal to the left colic artery. In 2008 Chin et al4 reviewed 1,389 individuals who underwent high ligation of the IMA. The authors identified IMA nodal metastases in 3.1% of patients. Of patients with rectal cancer and IMA metastases, the 5-year diseasefree survival was 13.8%. The authors concluded that IMA node positivity is a harbinger of systemic disease, and high ligation of the IMA for rectal cancer benefited only 0.4% of patients. In 2014 Ubukata et al5 reviewed data from the registry of the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. The authors found that only 2.7% (67 of 2,446) of patients with a low rectal cancer who underwent resection with high ligation of the IMA had positive lymph nodes proximal to the left colic artery. Among patients with IMA lymph node involvement in whom an R0 resection was achieved, the 5-year overall survival was 68.8%, and the 5-year recurrence-free survival was 53.9%, which was not statistically different from the outcomes for individuals without IMA-positive lymph nodes. The authors concluded that the equivalent outcome between those with and without IMA lymph node involvement justified routine high ligation.

Several systematic reviews have failed to identify a clear benefit from routine high ligation. Lang et al6 in 2008 conducted a systematic literature review concerning the level of ligation in rectal cancer surgery and concluded that inadequate evidence exists to adopt standardization of high ligation of the IMA. Additionally, the authors did not find differences in proximal limb perfusion, length, or autonomic nerve innervation to support high or low ligation. In 2008, Titu et al7 performed a similar review and found no consistent oncologic advantage to high ligation but that complication rates between high and low ligations were similar. The authors concluded high ligation should be performed because the technique likely provided greater lymph node sampling and therefore more accurate staging. A subsequent meta-analysis by Cirocchi et al8 confirmed that high ligation was not associated with improved survival. Also, there was no difference in postoperative morbidity between patients who underwent high ligation and those who had low ligation.

Based on the available evidence, routine high ligation of the IMA above the origin of the left colic artery does not appear to affect outcomes and is therefore considered unnecessary. In the presence of clinical evidence of proximal IMA node involvement, however, high ligation should be performed both for complete staging and for locoregional control of disease.

Technical Aspects

The mesorectum may be mobilized from a lateral to medial or a medial to lateral approach. Regardless of which side the mobilization of the mesentery of the distal

sigmoid colon and rectum is initiated, there are three key components to mesenteric mobilization: (1) dissection of the retromesenteric plane posterior to the superior rectal artery; (2) avoidance of injury to the superior hypogastric nerve plexus, as injury to these nerves can result in retrograde ejaculation and bladder dysfunction; and (3) preservation of the integrity of the mesocolon in continuity with the mesorectum.

sigmoid colon and rectum is initiated, there are three key components to mesenteric mobilization: (1) dissection of the retromesenteric plane posterior to the superior rectal artery; (2) avoidance of injury to the superior hypogastric nerve plexus, as injury to these nerves can result in retrograde ejaculation and bladder dysfunction; and (3) preservation of the integrity of the mesocolon in continuity with the mesorectum.

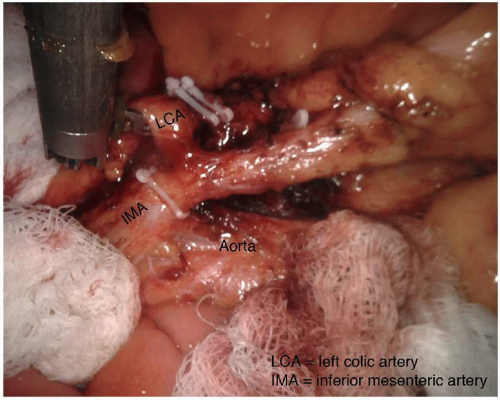

The dissection posterior to the superior rectal artery is continued cephalad to the proximal IMA, which is divided after visual confirmation of the origin of the left colic artery to ensure complete resection of the tumor-associated mesentery and lymph nodes. Additional length on the mesenteric artery may be obtained by also dividing the inferior mesenteric vein central to the tributary from the splenic flexure, along the inferior border of the pancreas, to permit rotation of the descending mesocolon along the radial axis of the left colic artery. If length is still insufficient, the left colic artery or the IMA proximal to the left colic artery may be divided to allow the descending mesocolon to reach further toward the pelvis (Fig. 4-2). During this dissection it is critical to identify and preserve the left ureter; this is facilitated by clearly identifying the IMA and its proximal branches. If the IMA and its branches are clearly identified prior to ligation, there is negligible risk for ureter injury. Mobilization of the splenic flexure is usually necessary to facilitate reach of the mesentery to the distal pelvis.

2. TOTAL MESORECTAL EXCISION

Recommendation: Total mesorectal excision should be performed for all patients with middle and low rectal cancers. This includes a complete excision of the rectum and all the pararectal lymph nodes within the mesorectum.

Type of Data: Retrospective comparison of prospective cohorts from randomized controlled trials and from prospective nonrandomized and retrospective studies.

Grade of Recommendation: Strong recommendation, high-quality evidence.

Rationale

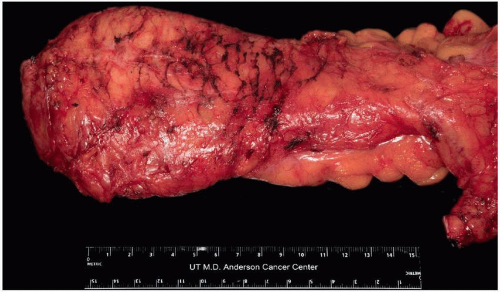

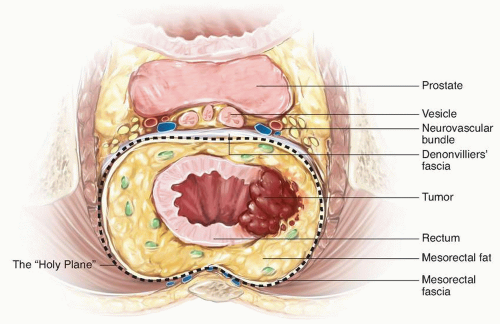

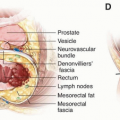

Total mesorectal excision (TME) of rectal cancer leverages existing tissue planes to perform a complete resection of the tumor and the associated draining lymph nodes.9 By maintaining the intact fascia propria of the rectum and operating in the space between the mesorectum and the presacral fascia, the surgeon can achieve a resection with a negative margin, while simultaneously preserving neurovascular structures and minimizing morbidity.

After introduction of the technique of TME, the Stockholm Colorectal Cancer Study Group examined the impact of the implementation of a surgical training program for TME on the operative and oncologic outcomes of their patients.10 Members of the group compared outcome data from two prior randomized trials to a trial of patients treated after deployment of training workshops on the TME technique. The data revealed significantly better oncologic outcomes in patients treated with TME. Specifically, local recurrence rates (14% and 15% vs. 6%, respectively) and the percentage of cancer-related deaths (16% and 15% vs. 9%, respectively) were both lower in patients who underwent TME. Additionally, TME was associated with a 50% higher rate of sphincter preservation.10

Similarly, the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group compared outcomes between conventional surgery and TME in patients undergoing curative treatment for rectal cancer on prior randomized clinical trials. Focusing strictly on the impact of surgical approach by excluding patients who received neoadjuvant radiotherapy, the authors demonstrated lower local recurrence rates with TME compared with conventional resection (9% vs. 16%, respectively). Furthermore, the type of surgery was an independent predictor of local recurrence on multivariate analysis.11

As shown in several studies, a complete mesorectum resulting from performing a TME in the proper tissue plane results in lower rates of local and distant recurrence than resection with an incomplete mesorectum.12,13 Pathologic assessment of the surgical specimen therefore can and should provide direct feedback to the operating surgeon regarding the quality of the operation (Fig. 4-3).

Technical Aspects

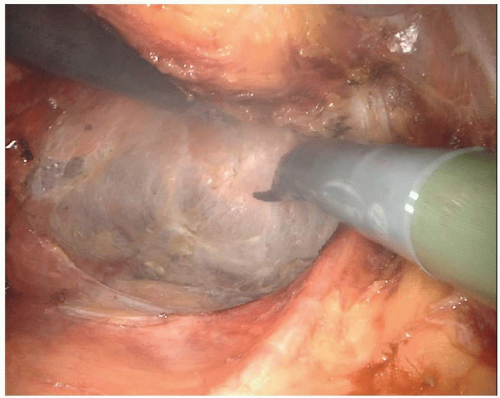

TME begins by identifying the posterior plane at the level of the sacral promontory. This is the easiest location at which to identify the areolar tissue plane along the posterior aspect of the fascia propria of the rectum. It further allows for the identification of the superior hemorrhoidal vessels, the ureter, and the hypogastric nerve trunks. Once this plane is established, the dissection continues posteriorly with division of

the areolar tissue between the visceral mesorectal fascia and parietal presacral fascia down to the pelvic floor (Figs. 4-4 and 4-5). Defining the posterior plane enhances the visualization of the lateral mesorectal plane. Dissection along these planes will include the division of the middle rectal vessels. Care should be taken during lateral dissection to identify the hypogastric nerve trunks, which run posterolateral to the mesorectum and medial to the endopelvic fascia. Injury to these nerves will result in retrograde ejaculation and impaired bladder accommodation.

the areolar tissue between the visceral mesorectal fascia and parietal presacral fascia down to the pelvic floor (Figs. 4-4 and 4-5). Defining the posterior plane enhances the visualization of the lateral mesorectal plane. Dissection along these planes will include the division of the middle rectal vessels. Care should be taken during lateral dissection to identify the hypogastric nerve trunks, which run posterolateral to the mesorectum and medial to the endopelvic fascia. Injury to these nerves will result in retrograde ejaculation and impaired bladder accommodation.

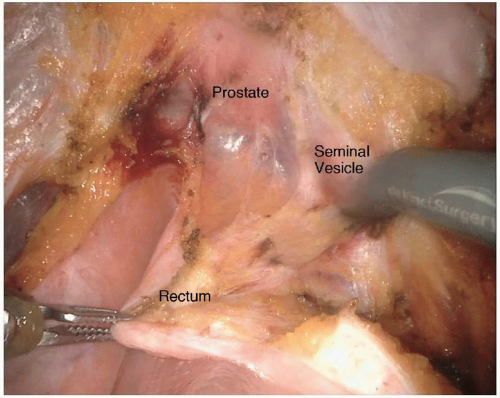

Lastly, the anterior plane of dissection proceeds posterior to the vagina or prostate. In a male patient, the anterior dissection can occur anterior or posterior to Denonvilliers’ fascia. Determining whether to include Denonvilliers’ fascia with the specimen is guided by the location of the rectal cancer. An anterior rectal tumor in the mid- to low rectum will often require resecting Denonvilliers’ fascia with the specimen. It is relevant to consider the appropriate anterior plane because the autonomic nerves are at risk of injury, terminating in the urogenital organs in the anterolateral location of the dissection. The autonomic nerves run along the lateral aspect of the pelvis and coalesce at the neurovascular bundles, which run along the posterolateral aspects of the prostate. They are at greater risk of injury with a plane of dissection anterior to Denonvilliers’ fascia or during the distal rectal dissection along the posterior aspect of the prostate gland. They are also commonly injured during dissection around the seminal vesicles. Overly aggressive use of cautery when bleeding is encountered along the seminal vesicles will often result in injury to the nervi erigentes, resulting in erectile dysfunction (Fig. 4-6). The circumferential dissection continues down to the pelvic floor with exposure of the bare rectum at the level of the anorectal ring. To accomplish this distal dissection, the surgeon must divide the retrorectal (Waldeyer’s) fascia to completely expose the bare rectum and provide adequate mobility for a low anastomosis.

3. LYMPH NODE DISSECTION

Recommendation: Standard lymphadenectomy should include pararectal lymph nodes included in the total mesorectal excision specimen. Removal of internal iliac or obturator lymph nodes should also be considered if clinically involved or in patients who have not received preoperative radiotherapy.

Type of Data: Several retrospective observational studies and a prospective randomized trial in which patients with identified lymphadenopathy were not treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Grade of Recommendation: Weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence.

Rationale

In a standard TME resection, the lateral extent of the dissection is the fascia that envelops the lateral portion of the mesorectum and adheres to the pelvic sidewalls. In a lateral lymph node dissection (LLND), the lymph node tissues are also resected from the common, external, and internal iliac arteries and are completely dissected from the obturator fossa while the ureter and obturator nerve are preserved.14 The role of LLND has historically been controversial.

Although relatively standard in Japan, this modification of the standard TME is not commonly utilized in North America or Europe. Because there has been significant controversy regarding its utility, Fujita et al15 undertook a randomized controlled trial to confirm that TME alone was not inferior to a TME combined with LLND. In this trial,

they randomly assigned 700 patients with stage II-III rectal cancer from 33 centers over 7 years to TME with or without LLND. Patients were staged with computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and only those with clinically negative lateral nodes (<1 cm) were included; patients with radiographic evidence of lateral node metastases ≥10 mm were excluded. Surgical procedures were standardized, and the quality of the surgery was evaluated through submitted photographs. No patient received neoadjuvant therapy. Patients were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy as appropriate.

they randomly assigned 700 patients with stage II-III rectal cancer from 33 centers over 7 years to TME with or without LLND. Patients were staged with computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and only those with clinically negative lateral nodes (<1 cm) were included; patients with radiographic evidence of lateral node metastases ≥10 mm were excluded. Surgical procedures were standardized, and the quality of the surgery was evaluated through submitted photographs. No patient received neoadjuvant therapy. Patients were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy as appropriate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree