Interventional radiology for the cancer patient

Judy U. Ahrar, MD  Michael J. Wallace, MD

Michael J. Wallace, MD  Rony Avritscher, MD

Rony Avritscher, MD

Overview

In the past decades, there has been a substantial expansion in the use of image–guided procedures for diagnosing and treating various types of cancer. Percutaneous biopsy is usually the first step in obtaining a definitive diagnosis and aids in the development of the treatment plan. Patients with primary or metastatic disease involving the liver are candidates for a wide range of image–guided interventions such as hepatic arterial embolization procedures, liver tumor ablation, and portal vein embolization. Cancer patients also benefit from a variety of palliative image–guided interventions, such as vena cava filter placement, biliary drainage and stent placement, and renal artery embolization, to name a few. Interventional radiology offers a multitude of minimally invasive procedures that are a key component in the management of cancer patients.

In the past decades, there has been a substantial expansion in the use of image-guided procedures for diagnosing and treating various types of cancer. There are several reasons for this increased use. Advances in cancer diagnosis and novel medical and surgical therapies have led to increased survival in this patient population. Owing to the prevalence of imaging, more patients now present with primary or metastatic disease confined to an organ and, consequently, are more likely to benefit from locoregional therapies than from systemic treatment. Thus, a neoplasm can be defined using standard imaging modalities, and then minimally invasive percutaneous techniques can be used to establish the diagnosis and provide locoregional or palliative therapies to treat the cancer patient. Recent improvements in catheter/device technology, embolic agents and chemotherapy drugs, and delivery systems are associated with improved patient outcome and have sparked renewed interest in these approaches. In this chapter, we discuss hepatic vascular interventions, genitourinary interventions, thoracic interventions, several forms of palliative therapeutic procedures, and some additional image-guided procedures (vena cava filter placement, biopsy, and intratumoral gene therapy).

Hepatic vascular interventions

The liver has long occupied center stage in interventional oncology, the practice of interventional radiology specific to the oncology patient. Hepatic interventions for diagnosis and treatment are popular for a number of reasons, among them being that this organ is a common site of metastatic disease and can be accessed easily percutaneously. However, the key feature that makes liver tumors particularly amenable to catheter-delivered therapies stems from the unique nature of their blood supply. Hepatic tumors derive most of their blood supply from the hepatic artery, whereas normal hepatic parenchyma derives most of its supply from the portal venous system. This unique arrangement allows the interventional oncologist to treat hepatic lesions while sparing the surrounding normal liver.

Arterial infusion therapy

The goal of arterial infusion is to achieve better tumor response by delivering chemotherapeutic agents directly into the artery that supplies the neoplasm. The rationale behind arterial infusion therapy is based on the first-pass effect, which occurs when a drug is given directly into the tissue that metabolizes it. The first-pass effect, compared with systemic administration, can lead to a several-fold increase in the drug concentration within the affected organ and, at the same time, a reduction in systemic concentration. Therefore, regional drug delivery is seen as a method of overcoming the limitations of the maximum-tolerated dose.1

Arterial infusion therapy has been used primarily for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer confined to the liver. A meta-analysis by Mocellin et al. 2 summarized the results of 10 randomized controlled trials that compared hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) with systemic chemotherapy. Although the study revealed better tumor response to fluoropyrimidine-based HAI than systemic fluoropyrimidine therapy, tumor response rates for modern systemic chemotherapy regimens using a combination of fluorouracil with oxaliplatin or irinotecan were similar or superior to those for HAI. Moreover, the meta-analysis showed no survival benefit associated with fluoropyrimidine-based HAI therapy. Further studies of the use of HAI for the delivery of novel anticancer agents will be instrumental in determining the role of this approach in future locoregional cancer therapy.

Arterial embolization

The aim of transcatheter hepatic arterial embolization is to completely or partially occlude the arterial supply to the tumor. The rationale is that such occlusion will cause tumor ischemia, which in turn will lead to growth arrest and necrosis. After hepatic arterial embolization, collateral hepatic circulation comes into play immediately. This collateral circulation should be traced and occluded if it supplies the neoplasm. The more central the occlusion, the more abundant is the collateral flow. Therefore, to maximize ischemia, the most effective embolization should result in distal terminal vessel occlusion. Peripheral (segmental and subsegmental) vascular embolization is best accomplished with coaxial catheters and small particles.

Many different embolic agents have been used with success for hepatic embolization. The most common agents include absorbable gelatin sponge particles and powder, polyvinyl alcohol foam granules, fibrin glue, n-butyl cyanoacrylate, ethiodized oil, microspheres, and absolute alcohol. Gelatin sponge segments or stainless steel coils are used for central occlusion and not often used for tumor embolotherapy.

The most common complication after hepatic arterial embolization is postembolization syndrome. This syndrome consists of fever, nausea, fatigue, and elevated white blood cell count and liver function tests. These symptoms are usually self-limited. Complications resulting from nontarget embolization include cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and gastrointestinal ulcers. Hepatic embolization may also lead to liver necrosis, hepatic abscess, and liver failure. Failure to recognize intrahepatic arteriovenous shunts during embolization may cause embolic material to reach the pulmonary circulation, which can in turn lead to respiratory failure. The complications of hepatic embolization in 284 patients who underwent 410 embolizations over a 10-year period were analyzed by Hemingway and Allison.3 Minor complications occurred in 16% of patients, serious complications in 6.6%, and death in 2%.

Arterial chemoembolization

Arterial chemoembolization consists of intra-arterial delivery of a combination of chemotherapy drugs and an embolic agent into a liver tumor. The rationale behind chemoembolization is based on the theory that tumor ischemia caused by embolization of the dominant arterial supply has a synergistic effect with the chemotherapeutic drugs. This technique has been the mainstay of interventional radiology since it was introduced by Yamada in 1977.4 The introduction of iodized oil, an iodinated ester derived from poppy-seed oil, advanced this technique significantly. Iodized oil is well suited for chemoembolization because of its preferential tumor uptake by hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and certain hepatic metastases; it acts simultaneously as an embolic agent and a vehicle for the chemotherapeutic agent.5, 6 These findings are explained partially by the concept of enhanced permeability and retention suggested by Maeda et al.7 Newly formed tumor vessels are more permeable. This increased permeability coupled with a lack of lymphatics in the neoplasm results in retention of molecules of higher molecular weight within the tumor interstitium for a more prolonged period. This retention may explain, in part, the accumulation of iodized oil or the increase in concentration of polymer conjugates of chemotherapeutic agents in neoplasms.

There are many different chemoembolization protocols. The most commonly used chemotherapy agent is doxorubicin, which is combined with cisplatin and mitomycin C. Subsequently, these chemotherapeutic agents are mixed with iodized oil and infused slowly into the hepatic artery branch that feeds the tumor. Drug-eluting beads, which are microspheres loaded with chemotherapy agents (doxorubicin and irinotecan), have recently come into common use for chemoembolization. Additional embolization with gelatin sponge or particles can be performed to enhance tumor ischemia. The proximal arterial supply to the tumor should be preserved because increased response is observed with repeated procedures.

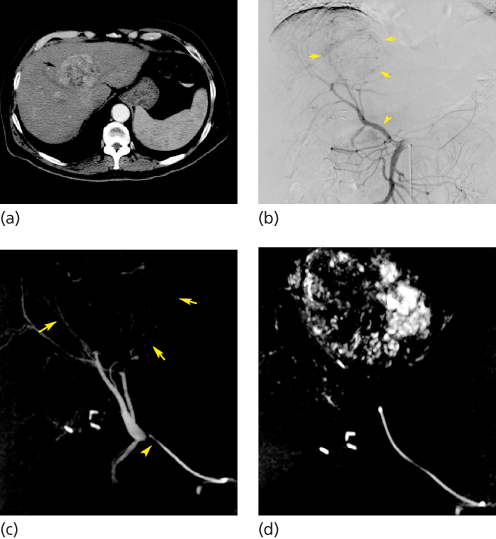

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization has been used to treat unresectable HCC, cholangiocarcinomas, and hepatic metastases and has been used in conjunction with liver resection or tumor ablation or as a bridge to liver transplant. Two randomized clinical trials8, 9 showed a survival advantage when chemoembolization was performed in selected HCC patients. Recent advances in chemotherapy agents and embolic material suggest future potential for this technique. Incorporation of antiangiogenic agents into the mixture to be delivered to the tumor is being investigated.10, 11 Moreover, advances in technology now allow intraprocedural acquisition of cross-sectional images using C-arm cone-beam computed tomography (Figure 1). This technique enables more selective embolization as multiplanar and three-dimensional images are used to understand the arterial anatomy and assess completeness of embolization.12

Figure 1 Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization performed in a 71-year-old man with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. (a) Contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained before chemoembolization shows a large, solitary, hypervascular mass in segment IV of the liver (arrow). (b) Anteroposterior digital subtraction angiography (DSA) of the abdomen shows a replaced right hepatic artery arising from the proximal superior mesenteric artery (arrowhead). This vessel supplies the hypervascular tumor in the left liver (arrows). (c) C-arm cone-beam CT images obtained during the procedure show tip of 3-French catheter in the distal replaced right hepatic artery (arrowhead) confirming origin of vascular supply to the hepatocellular carcinoma (arrows). (d) C-arm cone-beam CT images obtained after chemoembolization demonstrate retention of iodized oil throughout the lesion.

Hepatic intra-arterial brachytherapy

Radioembolization with yttrium-90 (90Y) microspheres is a technique in which particles incorporating the isotope 90Y are infused through a catheter directly into the hepatic arteries. Yttrium-90 is a beta emitter with a short half-life. The concept is similar to chemoembolization in that the injected particles are distributed selectively into the tumor arterial bed. This distribution is possible because the arterial blood flow within the tumor is several times greater than the flow in the surrounding liver parenchyma. Consequently, a much higher amount of radiation can be delivered to the lesion than with external-beam radiation, and at the same time, the potential for radiation-induced hepatitis is reduced.

TheraSphere beads (MDS Nordion, Ottawa, Canada) are FDA approved for neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable HCC in patients with portal vein thrombosis or as a bridge to transplantation. SIR-Spheres (Sirtex Medical, Lane Cove, Australia) with concomitant use of floxuridine is approved for the treatment of colorectal cancer metastatic to the liver. Knowledge of the vascular anatomic variants in the celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery is critical to administering this therapy safely to avoid nontarget embolization of the radioactive microspheres, which can have devastating consequences. Multiple studies have demonstrated the safety of radioembolization with yttrium-90 for the treatment of unresectable HCC and metastatic colorectal cancer.13–15

Local tissue ablation

Image-guided tumor ablation of focal hepatic malignancies can be accomplished using chemical agents or thermal energy. Chemical ablation options include direct intratumoral percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) and ablation using hot water or saline, acetic acid, or chemotherapeutic agents that induce tumor cell death. Thermal ablation options include high-energy radiofrequency (RF), interstitial laser photocoagulation, microwave, cryotherapy, and high-intensity focused ultrasound that causes coagulation necrosis. These procedures can be performed under imaging guidance by interventional radiologists or surgeons in the operating suite.

Ethanol is the most commonly used agent for chemical tumor ablation worldwide.16 Once ethanol is injected into the tumor, it causes cytoplasmic dehydration, denaturation of cellular proteins, and small-vessel thrombosis.17 PEI is well established for the treatment of HCC, but it is much less successful in the treatment of hepatic metastases; in metastases, thermal ablation methods are more promising. This distinction appears to stem from the way in which ethanol disseminates within the different tumors. The distribution of ethanol tends to be uniform in soft lesions surrounded by hardened cirrhotic liver parenchyma, as is the case in HCC. However, when the surrounding parenchyma is softer than the tumor, as is often the case with metastases, ethanol distribution is less uniform and the treatment is less effective. Ebara et al.18 reported on 20 years of experience with PEI for HCC lesions ≤3 cm in a total of 270 patients. The local recurrence rate at 3 years was 10%, with overall 3- and 5-year survival rates of 81% and 60%, respectively.

Livraghi et al.19 studied RF ablation versus PEI in the treatment of small HCCs (≤3 cm in diameter). Complete necrosis was achieved in 47 of 52 tumors (90%) in an average of 1.2 sessions per tumor with RF ablation and 48 of 60 tumors (80%) in an average of 4.8 sessions per tumor with PEI. One major complication (hemothorax) and four minor complications (bleeding, hemobilia, pleural effusion, and cholecystitis) occurred with RF ablation, although there was none with PEI. Lencioni et al.20 reported treatment of HCC with either RF ablation or PEI in a randomized series of 102 patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Although there was no overall difference in 1- and 2-year survival, there was a significant difference in 1- and 2-year local recurrence-free survival (98% for RF ablation vs 83% for PEI at 1 year and 96% vs 62% at 2 years). The study was limited to patients with either a single HCC ≤5 cm in diameter or a maximum of three HCCs ≤3 cm in diameter. However, up to 25% of the lesions in Ebara and colleagues’ study18 of PEI could not have been treated by RF ablation because of anatomic considerations, which emphasizes that there is still a role for PEI in small tumors despite results that overall favor RF ablation. Thermal ablation for hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer has also been reported to improve survival. Median survival time after thermal ablation was increased to 39 months from 21 to 25 months in a study reported by Gillams and Lees.21

Portal vein embolization

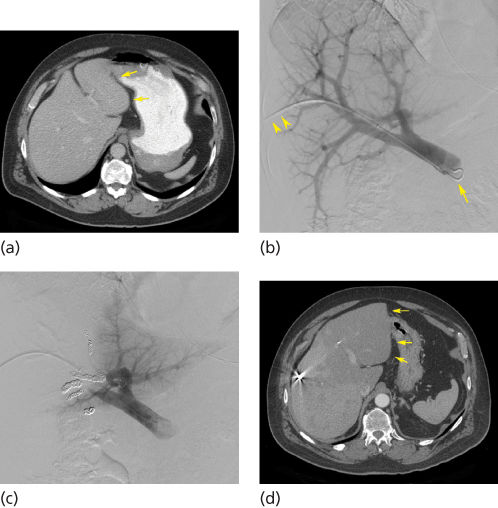

Successful resection of the liver depends on the function of the residual hepatic parenchyma. When the portal vein is occluded, hepatocyte growth factors (hepatopoietin A, insulin, and glucagon) are shunted into the liver segments supplied by nonembolized vessels.22 The result is atrophy of the segments supplied by the occluded vessels and hypertrophy of the other areas of the liver. Thus, portal vein embolization (PVE) is used preoperatively to induce liver hypertrophy in potential surgical candidates with anticipated marginal future liver remnant (FLR) volumes (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Transhepatic ipsilateral right portal vein embolization (PVE) extended to segment IV using Tris-acryl particles and coils performed in a 52-year-old man with rectal cancer metastatic to the liver. (a) CT scan obtained before PVE shows marginal future liver remnant (FLR) [FLR-to-TELV (total estimated liver volume) ratio = 17%] (arrows). (b) Anteroposterior DSA portogram shows a 6-French vascular sheath in a right portal vein branch (arrowheads) and a 5-French flush catheter within the main portal vein (arrow). (c) Final DSA portogram shows occlusion of the portal vein branches to segments IV through VIII with continued patency of the vein supplying the left lateral liver. (d) CT scan obtained 1 month after right PVE extended to segment IV shows substantial FLR hypertrophy (FLR-to-TELV ratio = 27%) (arrows). The degree of hypertrophy is 10%.

PVE is performed if the FLR is estimated to be <20% of the estimated total liver volume (TLV) in patients without underlying liver disease, <30% of TLV in patients with underlying severe liver injury, and <40% of TLV in patients with cirrhosis.23 For embolizations performed before extended right hepatectomy, modification of the preoperative embolization to include segment IV may optimize liver hypertrophy. The range of reported mean absolute FLR increase for PVE in general was 46–70%, depending on the particle type used for embolization. PVE results in hepatocyte apoptosis, so the postembolization syndrome associated with transarterial embolization and necrosis does not occur. Madoff et al.24 reported on 44 patients who underwent PVE before major liver surgery. None of the patients developed liver failure after the resection.

Fibrin glue, gelatin sponge, thrombin, particles, coils, and absolute ethanol all have been used for PVE. In the United States, a combination of particles and embolization coils is the most common embolic agent.

Retrospective studies and meta-analysis suggest improved surgical outcomes after PVE.23, 25 For this reason, PVE before a major hepatectomy is now considered the standard of care in many comprehensive hepatobiliary centers worldwide.

Considerations in hepatocellular carcinoma

HCC is the fifth most prevalent type of cancer and the third most common cause of cancer death in the world.26 This disease is common worldwide because of its strong association with underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatitis. Surgical removal of the tumor is the only potentially curative treatment. However, curative resection is possible only in 20–30% of patients.27 Recurrence rates after surgical resection are high because of dissemination of primary disease, undetected hepatic micrometastases, or metachronous lesions. Five-year survival after partial hepatic resection is approximately 50%.28 For patients with cirrhosis and unresectable disease, liver transplantation can potentially cure both the underlying liver disease and the tumor. Intra-arterial therapies (embolization, chemoembolization, and radioembolization) and ablative techniques are viable alternatives in patients who are not candidates for partial hepatectomy or transplantation. Systemic chemotherapy for HCC has been disappointing because of the low response rates. In recent times, sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic, proapoptotic, and Raf kinase-inhibitory activity, has been shown to be well tolerated; it is the first agent to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in overall survival for patients with advanced HCC.29

Local etiologic factors have to be evaluated when considering locoregional therapy because HCC in western countries is often different from the typical HCC treated by interventional radiologists in Japan and the far east.30 Nodular HCC is seen in fewer than 25% of western patients but is seen in approximately 75% of patients in Japan. For patients with early to intermediate disease, ablative techniques are appealing, as the damage to the surrounding liver parenchyma is minimized, allowing for repeated treatments and serving as a bridge to transplantation. The current literature supports the use of percutaneous RF ablation in patients with HCC and either a single lesion <5 cm in diameter or up to three lesions <3 cm in diameter if partial hepatic resection or transplantation is not available.31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree