Preoperative Staging

The preoperative staging workup includes digital rectal examinations, transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) , colonoscopy, abdominopelvic computed tomography scanning, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) , and positron emission tomography scanning. Preoperative CRT is considered for patients with bulky and/or tethered tumors that TRUS and pelvic MRI determine to be at clinical stages T3–T4 or if clinically positive lymph node metastases are detected. Pelvic MRI is widely used for preoperative regional staging of rectal cancer to determine the depth of rectal wall invasion, the presence of nodal metastases, and CRM involvement. The coronal and axial MRI planes reveal whether the anal sphincter or the levator muscle is involved in low rectal cancer that is very close to the anorectal ring around the level of the levator ani muscle [25, 26].

It is important to assess the depth of tumor invasion in low rectal cancer using MRI . T1 is defined as a tumor that is confined to the mucosa and submucosa, T2 is defined as a tumor that is confined to the muscularis propria, and T3 is defined as a tumor that has penetrated the rectal wall and involves the mesorectal fat. T4 is defined as a tumor that involves the visceral peritoneum (T4a) or the adjacent tissues (T4b), including those of the prostate, vagina, sacrum, and the pelvic side wall. Caution should be exercised when interpreting the depth of tumor invasion located at or below the levator muscles. Tumor invasion of the external anal sphincter is interpreted as stage T3, and tumor invasion of the levator muscles is interpreted as stage T4 [27–29]. To standardize MRI reporting, the MERCURY group suggested that low rectal cancer is defined when the lowest margin of the tumor is located at or below the upper border of the puborectalis muscle [29, 30].

Accurate restaging of tumors after preoperative CRT may help to determine optimal treatment strategies and reduce positive surgical margins. Unlike initial tumor staging, it is difficult to distinguish viable tumors from radiation-induced inflammation, necrosis, or fibrosis. Thus, the restaging accuracy of MRI is unsatisfactory, and in terms of the restaging accuracy of the T stage, the mean sensitivity and specificity have been reported to be 50.4% and 91.2%, respectively [31].

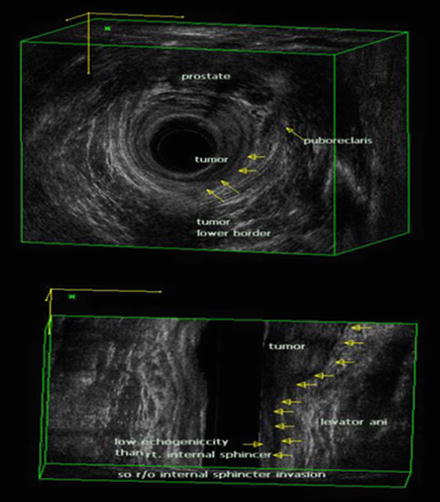

TRUS is useful when determining T1 or T2 disease because the higher-frequency sonoprobe has a higher resolution [32]. Katsura et al. [33] reported that the positive predictive values were 96.2% and 85.7% for T1 and T2 disease, respectively. Three-dimensional (3-D) ultrasound has become popular in recent years [34]. The 360° rotating ultrasound transducers have higher frequencies (6–16 MHz), and the system has an automated image reconstruction function. Multiplanar images can be obtained with 3-D TRUS, and it provides more comprehensive information with respect to the depth of tumor invasion and the relationships among the adjacent structures [35] (Fig. 12.2).

Fig. 12.2

Three-dimensional (3-D) transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) in a male patient. The relationship between rectal tumor and anal sphincter is well visualized by 3-D TRUS (BK Medical Systems, Herlev, Denmark). uT2 tumor at left lateral side shows a hypoechoic lesion representing disruption of the internal anal sphincter muscle

Indications

The ISR procedure is primarily indicated for patients with low rectal tumors within the surgical anal canal and where the tumor involves the internal sphincter [16, 24, 36–52]. If the tumor is located at the level of the puborectalis muscle and involves the external anal sphincter or levator ani muscle, APR remains the gold standard for surgical treatment. However, in some specific cases, more extensive resection techniques, including levator muscle excision and external sphincter excision, have been explored to preserve the anal sphincter [18–20, 22].

Good surgical outcomes can be anticipated when the tumor is staged at T1–T3, mobile, confined to less than 50% of the rectal circumference and has well-to-moderately differentiated histological grade and when the patient has a good performance status, with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of 0–2, and good anal function.

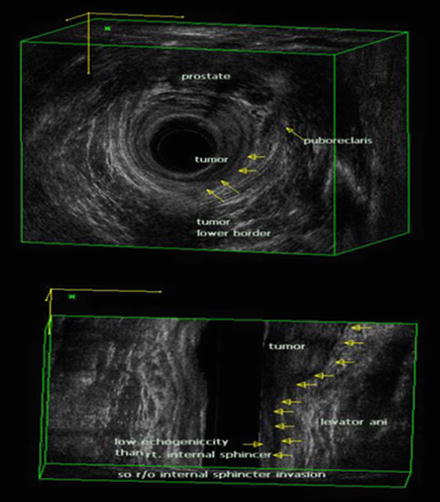

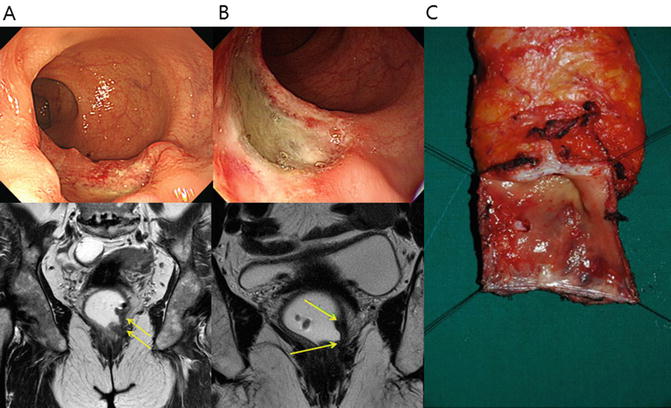

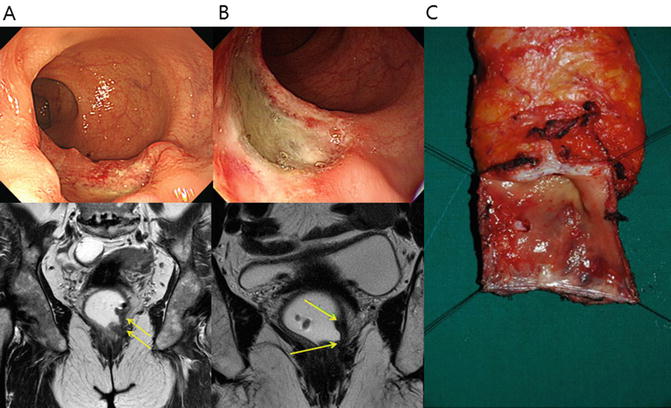

Standard management of locally advanced rectal cancer now is comprised of preoperative CRT followed by radical resection [53, 54]. Preoperative CRT reduces tumor bulk and increases the probability of sphincter preservation surgery. Indeed, sphincter-preserving surgery can be achieved in a large proportion of patients who undergo CRT [55]. Preoperative CRT is associated with a pathologic complete response rate of 4–31%, which is associated with good oncologic outcome in terms of both recurrence and survival [56] (Fig. 12.3).

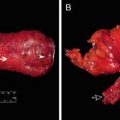

Fig. 12.3

Preoperative chemoradiation therapy (CRT) and intersphincteric resection (ISR) in a 64-year-old female patient with low rectal cancer. (a) Before preoperative CRT, the rectal tumor was located 3 cm from the anal verge, and pretreatment magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows suspected tumor invasion to the internal anal sphincter muscle on T2-weighted coronal image. (b) After preoperative CRT, the depth of main tumor invasion was downstaged based on posttreatment colonoscopy and MRI. T2-weighted coronal image shows posttreatment fibrosis with decrease in signal intensity. (c) Surgical specimen after ISR. Suspicious invasion on preoperative MRI was replaced with fibrosis. Final pathology report confirmed 4 mm tumor-free circumferential margin

Coloanal Reconstruction

To date, several methods for coloanal reconstruction after proctectomy have been described (Table 12.1). In terms of the shape of the proximal colon, the current options for coloanal reconstruction include straight CAA (end-to-end), J-pouch reconstruction, coloplasty, and side-to-end anastomoses, and either hand-sewn or stapled anastomoses are performed. When performing a stapled anastomosis, 10–15 mm of distal remnant anoderm is incorporated into the circular stapler. In addition, the external anal sphincter may become entrapped within the stapler, and the pelvic cavity should be wide enough for the creation of a stapled anastomosis. Accordingly, the hand-sewn anastomosis is the gold standard following subtotal or total ISR. A hand-sewn anastomosis has the advantages of being easy, simple, and familiar to surgeons. In addition, it can be performed conveniently in a narrow and deep pelvis.

Table 12.1

Methods of coloanal reconstruction

Colon configuration | Anastomosis | Fecal diversion (%) | Type of stoma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Schiessel et al. [9] | End-to-end | Hand-sewn | 100 | Colostomy |

Braun et al. [52] | End-to-end | Hand-sewn, stapled | NS | Colostomy, ileostomy |

Rullier et al. [14] | End-to-end, J-pouch | Hand-sewn, stapled | 100 | Colostomy, ileostomy |

Teramoto et al. [57] | End-to-end | Hand-sewn | 100 | Colostomy |

Watanabe et al. [58] | End-to-end | Hand-sewn | 100 | Ileostomy |

Akasu et al. [59] | End-to-end, J-pouch, coloplasty | Hand-sewn | 87 | NS |

Kim et al. [60] | End-to-end, J-pouch | Hand-sewn | 100 | Ileostomy |

Since its first description by Parks and Percy [12], the straight (end-to-end) anastomosis has been the most commonly used method for CAA. In their study, 69 of the 70 patients were either fully continent (n = 39) or they had only minor bowel dysfunction (n = 30), and only one patient was incontinent. The main symptoms of bowel dysfunction were frequency and irregular bowel movements. Anterior resection syndrome refers to a broad spectrum of bowel habit changes that range from irregular bowel movements to fecal incontinence or defecation difficulty following low anterior resection. The incidence of anterior resection syndrome has been reported to be about 30% among patients who have undergone low anterior resection, and the quality of life is likely to be impaired in affected individuals [61, 62]. A reduction in the reservoir capacity is thought to be one reason for anterior resection syndrome; therefore, a colonic pouch is devised to increase the neorectal reservoir capacity [63, 64].

A colonic pouch is a surgically constructed neorectal reservoir. A J-shaped pouch is commonly used because it is simple and easy to construct. Lazorthes et al. [63] observed that a colonic J-pouch increased the maximum tolerated volume and reduced the frequency of bowel movements. In their study, 60% of the patients with pouches and 33% of the patients without pouches produced one or two stools per day during the first year. After 1 year, 86% of the patients with pouches and 33% of the patients without pouches had one or two bowel movements per day. Parc et al. [64] evaluated the functional results from 31 patients who had J-pouches, and they found that there was no incontinence and that the mean number of bowel movements was 1.1 per day; however, 25% of the patients eventually required enemas to defecate.

Some controversies remain regarding the use of J-pouches in relation to the optimal length of the pouch, the use of the sigmoid colon, and long-term functional outcomes. The length of the J-pouch has varied from 5 cm [65], 6 cm [63], 7 cm [66], 8 cm [64], 9 cm [67], 10 cm [65], to 12 cm [63]. However, lengthy pouches develop defecation dysfunction, including the inability to evacuate bulky stools, tenesmus, or the need for regular enemas [63, 64, 66–71]; hence, the length has been reduced to 5–6 cm. Indeed, Ho et al. [72] demonstrated that small J-pouches that are 5 cm long retain liquid stools well, and 6–8-cm-long pouches are now recommended.

The use of the sigmoid colon for the creation of J-pouches is another issue. Traditionally, both the sigmoid and descending colon have been used; however, disadvantages associated with the use of the sigmoid colon have been suggested, and these include diverticular disease, bulky mesentery, and motility problems. Seow-Choen [73] suggested that the sigmoid colon contributes to evacuatory dysfunction because defecation difficulties were observed in 25% of patients who had pouches created using the sigmoid colon [74], but these difficulties were not seen in patients who had pouches created using the descending colon [70, 75].

It is unclear whether the beneficial effects of J-pouches on bowel function are maintained in the long term [76, 77]. Defecatory function improves with time, even after straight CAA, because of an increase in the neorectal reservoir volume, the improvement in sphincter function, the recovery of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, and improvements in neorectal sensations [78, 79]. Ho et al. [80] observed that stool frequency and the incidence of incontinence were lower at 6 months in patients with pouches, but that the benefit was not sustained 2 years after surgery. Meanwhile, Harris et al. [81] demonstrated that 5–9 years after surgery, patients with J-pouches had better long-term outcomes with respect to their Kirwan continence scores, their evacuation difficulties, and urgency associated with defecation compared with patients with straight CAA.

The colonic J-pouch is created as described next. The two loops of the descending colon are anastomosed in a “J” configuration using a linear stapler. The appropriate pouch length is 5–8 cm, and the linear stapler may be inserted through the uppermost or lowermost parts of the J-pouch. The enteroenterostomy site is carefully inspected for any bleeding along the staple line, and hemostatic sutures are applied at the site of any bleeding. Then, hand-sewn or stapled anastomoses are performed.

Coloplasty refers to a colonic reservoir that is created by a longitudinal incision with a transverse closure using a method that is analogous to that of the Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty. Z’graggen et al. [82, 83] originally described this technique in a pig model, and Fazio et al. [84, 85] applied it to low colorectal or coloanal anastomoses. A reservoir for the coloplasty is made by a longitudinal incision, which is 8–10 cm long, along the teniae coli on the antimesenteric side. The colonic incision is stopped 4–6 cm proximal to the distal end of the colon, the colostomy is closed transversely using absorbable sutures, and then a stapled or hand-sewn anastomosis is performed with a prepared reservoir. Remzi et al. [86] demonstrated that the coloplasty group had fewer night bowel movements, fewer bowel movements per day, less clustering, and less antidiarrheal agent use than the straight anastomosis group. Coloplasty is a good alternative technique when a colonic J-pouch is technically difficult; however, there is more limited support of its benefit when compared to straight reconstruction than there is for a colonic J-pouch.

The side-to-end anastomosis was described for colorectal anastomoses in 1950, and its theoretical advantages include technical ease, a blood supply, and a larger anastomosis lumen [87]. Huber et al. [88] compared colonic pouches with side-to-end anastomoses after low anterior resections. The defecation frequencies were 2.2 and 5.4 per day at 3 months and 2.3 and 3.1 per day at 6 months in the pouch and side-to-end anastomosis groups, respectively. The investigators pointed out that the side-to-end anastomoses showed satisfactory long-term function and that the major benefit associated with the colonic pouches was seen during the immediate postoperative period. Machado et al. [89] observed that the colonic J-pouch and side-to-end anastomosis had comparable functional outcomes 2 years after low anterior resections.

When considering coloanal reconstruction , a straight (end-to-end) CAA is an easy, simple, and convenient reconstruction method, which is preferred after ISR. While J-pouch construction is performed to improve defecation function, it is not always possible, particularly in patients who have a narrow pelvis or bulky mesentery. Accordingly, surgeons should be cautious about the selection of the optimal coloanal reconstruction technique. While the J-pouch may be the first choice as opposed to the end-to-end CAA, alternatives such as a side-to-end CAA can be also considered.

Some additional technical considerations deserve mention. The use of irradiated sigmoid colons may cause anastomotic strictures or leakages [90]. Kim et al. [91] suggested that hand-sewn sutures between the levator muscles and the distal anorectal stumps may improve postoperative defecatory function. Yamada et al. [38] reported that 4 out of 20 patients who underwent total ISR experienced postoperative mucosal prolapses of the neorectum, and mucosal excisions were later performed in all 4 patients. In our opinion, a redundant proximal colon may be a source of a prolapse, and the appropriate length of the proximal colon is just beyond the symphysis pubis (Fig. 12.4). Furthermore, anchoring sutures between the proximal colon and the levator muscles may prevent prolapse .

Fig. 12.4

Postoperative mucosal prolapse after intersphincteric resection

Excision of the External Anal Sphincter or Levator Ani Muscle

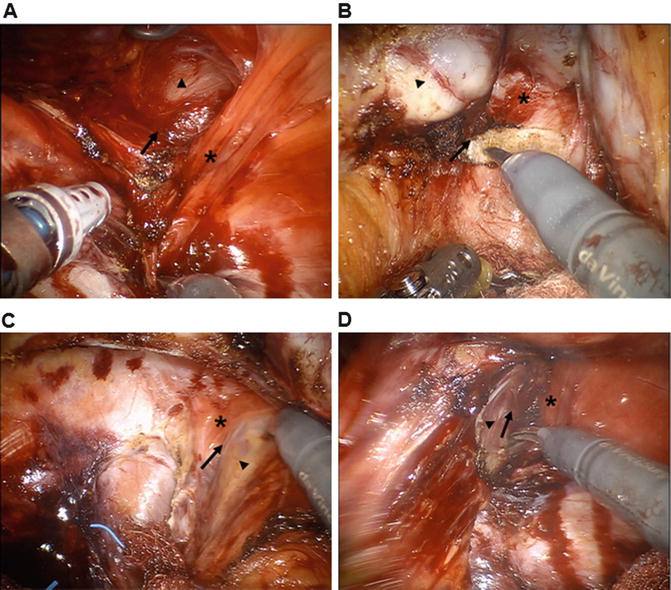

More extensive resections in addition to ISR have been described in the literature (Fig. 12.5). In 2002, Fucini et al. [22] described the excision of the levator muscles and the preservation of the part of the internal sphincter and the external sphincter and its innervation for low T4 rectal cancers. Shirouzu et al. [18] described the excision of the puborectalis muscle, deep and superficial external sphincter, and the internal sphincter muscles while preserving the subcutaneous external sphincter muscle. Cong et al. [20] described the partial longitudinal resection of the anorectal and sphincter muscles. This technique involves the unilateral removal of the sphincter complex as occurs in APR. Alasari et al. [19] described a hemi-levator excision through the intersphincteric plane by removing the levator ani and the deep external sphincter muscles. All of these new techniques need to be scrutinized with respect to oncologic efficacy and functional outcomes .

Fig. 12.5

External anal sphincter resection and levator muscle excision. (a) Excision of the levator and internal and external anal sphincter muscles while preserving distal parts of the internal and external sphincters and its innervation for low T4 rectal cancers described by Fucini et al. [22]. (b) Excision of the puborectalis muscle, deep and superficial external sphincter, as well as internal sphincter muscles while preserving subcutaneous external sphincter muscle described by Shirouzu et al. [18]. (c) Partial longitudinal resection of the anorectum and sphincter muscles described by Cong et al. [20]. This technique involves removal of all sphincter complex unilaterally such as abdominoperineal resection. (d) Hemi-levator excision through the intersphincteric plane by removal of the levator ani and deep external sphincter muscles described by Alasari et al. [19]

Applied Anatomy of the Anal Canal

The anal canal is the last part of the digestive tract, and the anatomical anal canal refers to a zone between the dentate line and the anal verge, and it is approximately 2–3 cm long. The surgical anal canal refers to the zone between the anorectal ring and the anal verge. It is about 4–5 cm long and is shorter in women. The anorectal ring refers the site where the rectum goes into the pelvic floor. The levator ani muscle forms the pelvic floor and it is attached to the pelvic sidewall. The levator ani muscle is composed of the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus muscles. During rectal dissections, the U-shaped puborectalis muscle and the surrounding levator ani muscles are easily seen in the form of a membranous sheet, and they sometimes adhere to the rectal proper fascia [92]. The anorectal ring is angled by the puborectalis muscle and is pulled anteriorly by the contraction of the puborectalis muscle [93]. The levator ani muscle is innervated by branches of the pudendal, inferior rectal, perineal , and sacral nerves [94, 95]. The anal canal is surrounded by the internal sphincter and the longitudinal rectal muscle layer, the external sphincter [96] and the coccyx are located posteriorly, the ischiorectal fossa is located laterally, the urethra is located anteriorly in men, and the lower part of the vagina is located anteriorly in women.

The internal sphincter is connected from the inner circular smooth muscle of the rectum supplied by autonomic nerve. The length of the internal sphincter muscle is about 2 cm and 3 cm on the anterior and posterior sides, respectively [97]. The mean thickness is 4.5–5.9 mm [98], and the internal sphincter muscle ends with a thickened edge that is 1–1.5 cm from the anal verge and constitutes the intersphincteric or Hilton’s groove. The intersphincteric groove is an important surgical landmark for rectal cancer surgery that is well palpated during digital rectal examination. The outer longitudinal muscle of the rectum gets thinner in the distal rectum and meets the fibers from the puborectalis muscle and forms a thin band. This band runs between the internal and external sphincters, and it spreads radially and penetrates the subcutaneous portion of the external sphincter and finally ends as a supporting structure for the hemorrhoidal plexus. The external sphincter muscle is a striated muscle that forms a cylinder around the internal sphincter. While it acts in concert with the puborectalis muscle, its innervation is different. The anal canal receives both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation that controls the action of the internal anal sphincter. The external sphincter is innervated by the perineal branch of the sacral nerve and the inferior rectal branch of the internal pudendal nerve [99].

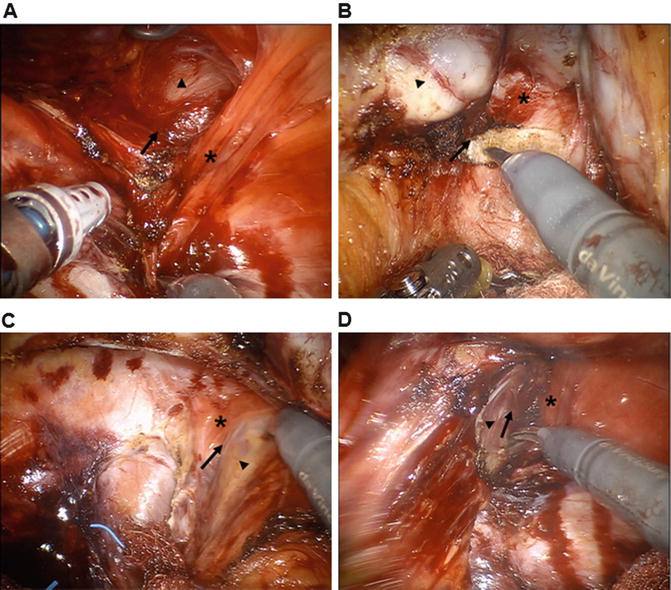

During operations for low rectal cancer, the anterior dissection is the most difficult part, and sometimes, surgeons may miss the proper dissection plane. Uchimoto et al. [100] emphasized the importance of the rectourethralis muscle based on a histologic study. They demonstrated that Denonvilliers’ fascia is absent at the level of the rectourethralis muscle and that the rectal wall is directly attached to the rectourethralis muscle. The anorectal veins and cavernous nerve are present around the rectourethralis muscle; thus, deeper dissection to the anterior surface of Denonvilliers’ fascia may cause unwanted bleeding or nerve injury. Neurovascular bundles cross the seminal vesicles in the 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock directions; therefore, unless the tumor is located anteriorly, the correct dissection plane is between the posterior side of Denonvilliers’ fascia and the rectal fascia proper [101–104]. Kinugasa et al. [105] highlighted that surgeons may overlook the correct surgical plane that lies between the ventral and dorsal layers of the anococcygeal ligament during per anal dissections (Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.6

Essential surgical anatomy for intersphincteric resection. Operative pelvic anatomy by robotic three-dimensional vision. (a) Posterior dissection through the intersphincteric plane (arrow) between the rectum (arrowhead) and the puborectalis muscle (asterisk). (b) Anterior surgical plane (arrow) behind the Denonvilliers’ fascia (asterisk). Seminal vesicle (arrowhead). (c, d) Left and right lateral dissection around the anal hiatus. Intersphincteric plane (arrow) is identified between the rectum (arrowhead) and the medial side of the puborectalis muscle (asterisk)

Preoperative Preparation

Mechanical bowel preparation is performed 1 day before surgery. The patient is fasted for 1 day before surgery and ingests 4 L of polyethylene glycol solution. A rectal glycerin enema is performed twice, once in the afternoon and once during the evening before the day of surgery. A first-generation cephalosporin is used as a prophylactic antibiotic and is administered just before surgery begins. Antibiotic treatment is maintained for 24–48 h after surgery. Preoperative chemical bowel preparation using antibiotics is not performed. Sequential compression stockings and subcutaneously administered low-molecular-weight heparin are considered for venous thrombosis prophylaxis .

Role of the Diverting Stoma

A diverting stoma is created by either a loop transverse colostomy or an ileostomy after ISR with CAA for rectal cancer. Although a diverting stoma does not prevent anastomotic leakages, the use of a diverting loop stoma does reduce symptomatic anastomotic leakages [2, 106]; thus, fecal diversion is cautiously considered after ISR.

Operative Technique

Details of the Operative Procedures

The operative procedures comprise three essential steps, namely, the first abdominal procedure, the second per anal procedure step, and the third step that comprises a second abdominal procedure.

Abdominal Procedure

Patient Position and Skin Incision

The patient is placed in the lithotomy-Trendelenburg position with the legs supported by stirrups. The laparotomy for the ISR procedure begins with a midline abdominal skin incision. After abdominal exposure, a mechanical self-retaining retractor is placed in position.

Ligation of the Inferior Mesenteric Artery

An incision is made at the level of the sacral promontory. A peritoneal incision extends along the right side of the rectal mesentery, and the avascular plane is exposed. The pedicle of the inferior mesenteric vessel is visualized, and the colonic mesentery is separated from the underlying fascia propria of the rectum and the inferior hypogastric nerves. The superior hypogastric plexus is carefully preserved around the aortic bifurcation, the inferior mesenteric artery is ligated at the root of its origin from the abdominal aorta, and the lymph nodes along the inferior mesenteric artery are cleared from just above the superior hypogastric nerves overlying the aorta. The inferior mesenteric vein is divided immediately beneath the pancreas. Older patients or patients with questionable blood supplies may be candidates for low ties of the inferior mesenteric artery.

Descending and Sigmoid Colon Mobilization via the Medial to Lateral or Lateral to Medial Approaches

During mobilization of the descending colon and the sigmoid colon, the locations of the ureter and the gonadal vessels are assessed and preserved.

Splenic Flexure Mobilization

The splenic flexure of the colon is routinely mobilized to gain a sufficient length for coloanal anastomosis . After ligation of the inferior mesenteric vein just below the inferior border of the pancreas , an avascular retroperitoneal space between the mesentery and Gerota’s fascia, including the perirenal fat, is developed. The loose attachment of the transverse mesocolon is separated from the lower border of the pancreas, and the lesser sac is entered. The left paracolic gutter is dissected, and the previously dissected retroperitoneal plane of Toldt’s fascia is identified. The greater omentum overlying the transverse colon is divided to enter the lesser sac, and the previous surgical plane is met at this point. Finally, any loose connective tissue is freed to complete the colonic mobilization, and the medial part of colonic mesentery is divided carefully, avoiding any injury to the marginal artery.

Total Mesorectal Excision

The pelvic dissection is continued along the parietal pelvic fascia, leaving the hypogastric nerve intact over the aorta. The proper rectal fascia enveloping the mesorectum should remain intact during the pelvic dissection. The autonomic pelvic plexus is also preserved. The rectum is sharply dissected to the anal hiatus of the pelvic diaphragm. The posterior rectal dissection is performed in the retrorectal avascular space along the visceral pelvic fascia plane. The rectosacral fascia or Waldeyer’s fascia is encountered at the S4 level between the presacral fascia and the rectal proper fascia. Division of the rectosacral fascia enables the surgeon to reach down to the level of the coccyx. The anterior rectal dissection involves the identification of Denonvilliers’ fascia in males.

Techniques to preserve the autonomic nerves are performed to preserve postoperative sexual and voiding function. A U-shaped incision during the excision of Denonvilliers’ fascia in the anterior part of the rectum helps to avoid injury of the genitourinary neurovascular bundles. In females, the rectum and the vaginal wall should be dissected carefully. The lateral part of the rectum is mobilized after the anterior and posterior dissections, while avoiding excessive traction of the rectum. The pelvic plexus and the arising sacral nerves are assessed and preserved [93]. The three common sites of nerve injury are the superior hypogastric plexus, the inferior hypogastric plexus, and the pelvic plexus .

Dissection to the Anal Canal Through the Intersphincteric Plane

The puborectalis muscle sling is exposed laterally, and the anococcygeal ligament is divided at the posterior side of the anal canal. The intersphincteric space is identified between the puborectalis muscle and the rectal wall. The dissection continues through the puborectalis muscle and in the deep part of the external anal sphincter at the intra-anal canal.

Per Anal Procedures

Assessment of the Lower Margin of the Tumor and the Distal Resection Margin

A Lone Star retractor (Lone Star Medical Products, Inc., Houston, TX, USA) is applied to the anus, and a rectal washout is performed using a solution of Betadine and saline. Then, 0.25% bupivacaine mixed with epinephrine is injected below the dentate line. The lower tumor margin is assessed, and a distal resection margin that is at least 1–2 cm long is obtained whenever possible.

Determination of Extent of ISR (Partial, Subtotal, or Total) and Circumferential Incision Around the Distal Margin

A digital rectal examination is performed to identify the intersphincteric groove, and the circumferential incision is made (Fig. 12.7). For more proximal lesions, the incised distal rectum may be closed to prevent contamination of the intraluminal contents.

Fig. 12.7

Perianal procedure for intersphincteric resection (ISR). Lower margin of the tumor is assessed, and proper type of ISR (partial, subtotal, or total) is selected. Digital rectal examination is performed to identify intersphincteric groove, and 0.25% bupivacaine mixed with epinephrine is injected below the dentate line (a). Circumferential incision is made along the intersphincteric groove (b)

Complete Mobilization of the Rectum to the Level of the Levator Ani Muscle

The posterior dissection begins at the level of the dentate line for partial ISR cases, between the dentate line and the intersphincteric groove for subtotal ISR cases, or at the intersphincteric groove for total ISR cases. The lateral and anterior dissections continue through the intersphincteric plane. Further posterior and lateral dissections continue, and the anterior attachment of the prostate or the vagina is eventually dissected. The rectal wall and the internal sphincter are sharply dissected just above the puborectalis sling along the surgical plane developed via the abdominal approach. The muscular rectal wall is freed using cautery at the level of the anorectal ring , and full mobilization is confirmed using the index finger.

Specimen Delivery

The specimen can be delivered either through the anus or through the abdominal wound. Care should be taken to avoid sphincter injury or tumor violation during specimen extraction. For patients with a bulky mesorectum or narrow pelvis, it may be difficult to deliver the specimen via the anus. The specimen is then transected with an adequate proximal margin .

Coloanal Reconstruction

The reconstruction type (J-pouch, end-to-end, side-to-end, or coloplasty) and method (hand-sewn or stapled) are selected. Splenic flexure mobilization is beneficial to ensure the acquisition of a sufficient colonic length . Anastomotic tension should be avoided. The mesocolon should not be twisted when the pouch is delivered into the pelvic cavity. The prepared proximal colon is pulled down through the anus. For hand-sewn anastomoses, a CAA is performed using absorbable 3-0 sutures placed in an interrupted fashion. Each suture should incorporate either external or internal sphincter muscles to provide anastomotic strength (Fig. 12.8). The proximal colon is then anastomosed to the anal mucosa or the external sphincter. For a stapled technique, a manual purse-string suture is made around the anoderm to facilitate the use of the circular stapler. The stapling technique is quick and technically convenient compared with hand-sewn anastomoses. However, as mentioned previously, stapled anastomoses may not be feasible in subtotal or total ISR cases.

Fig. 12.8

Hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis. Lone Star retractor (Lone Star Medical Products, Inc., Houston, TX, USA) is applied to the anus. End-to-end coloanal reconstruction with hand-sewn anastomosis is performed by absorbable 3-0 sutures in interrupted fashion. Anastomosis is positioned at the level of intersphincteric groove, not at the dentate line (a). Each suture should incorporate either external or internal sphincter muscles to provide anastomotic strength (b)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree