Viral Infections

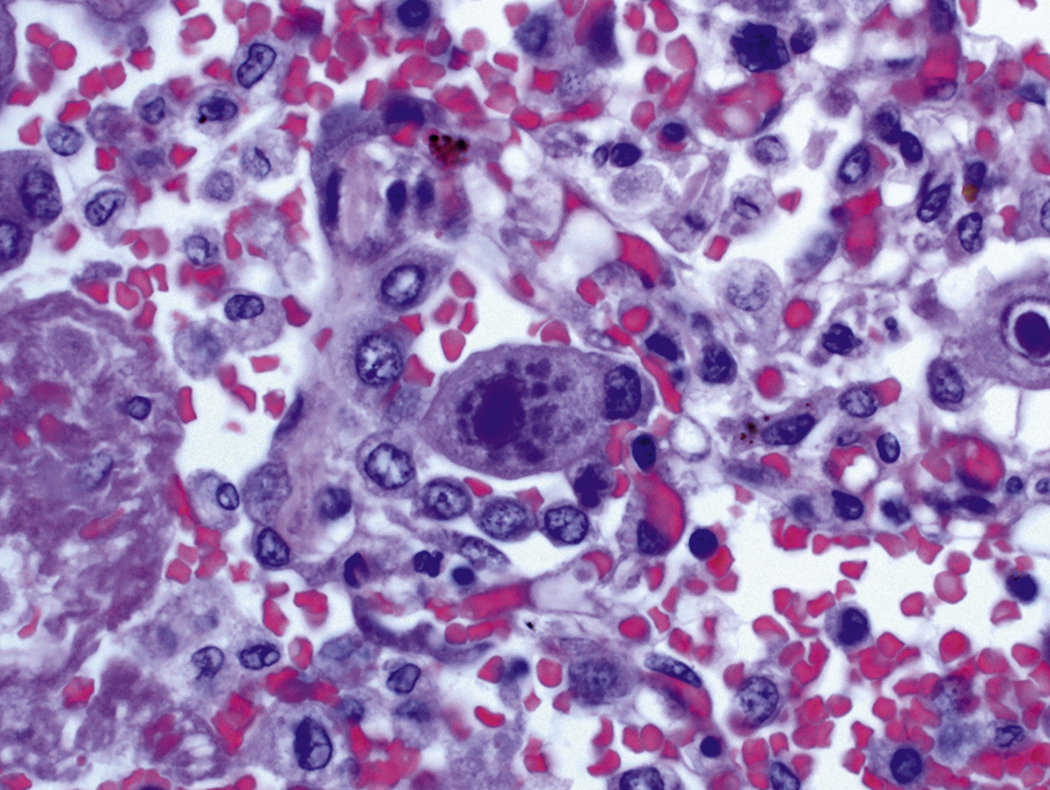

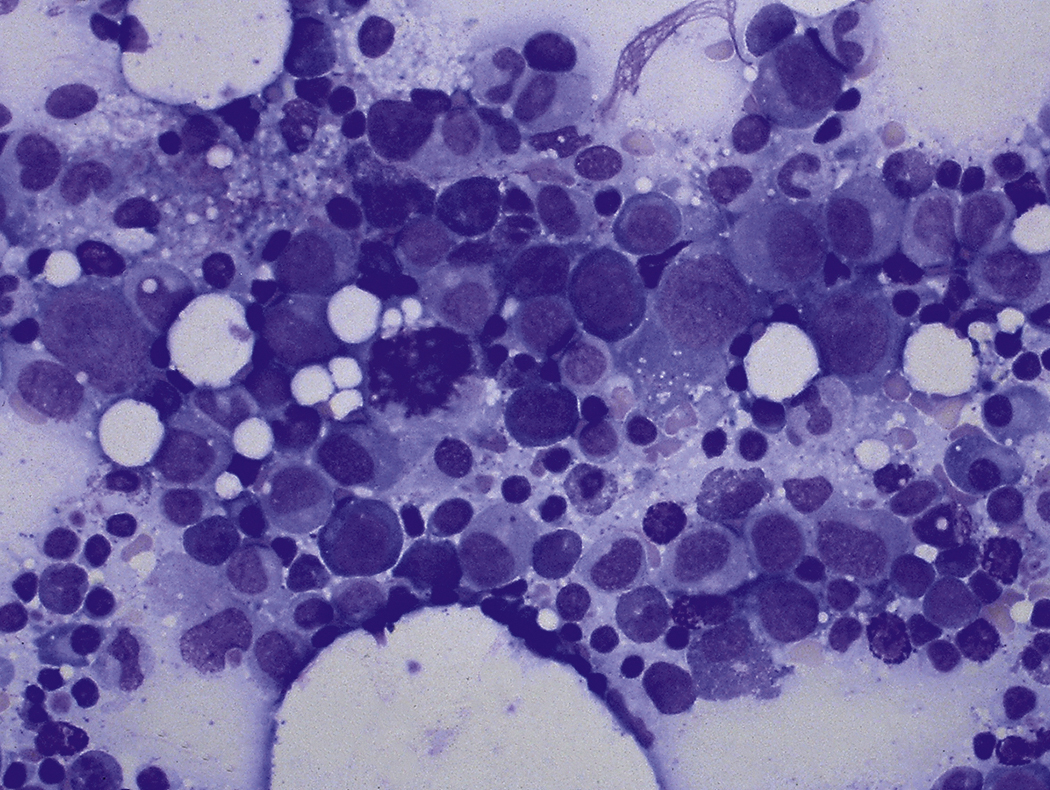

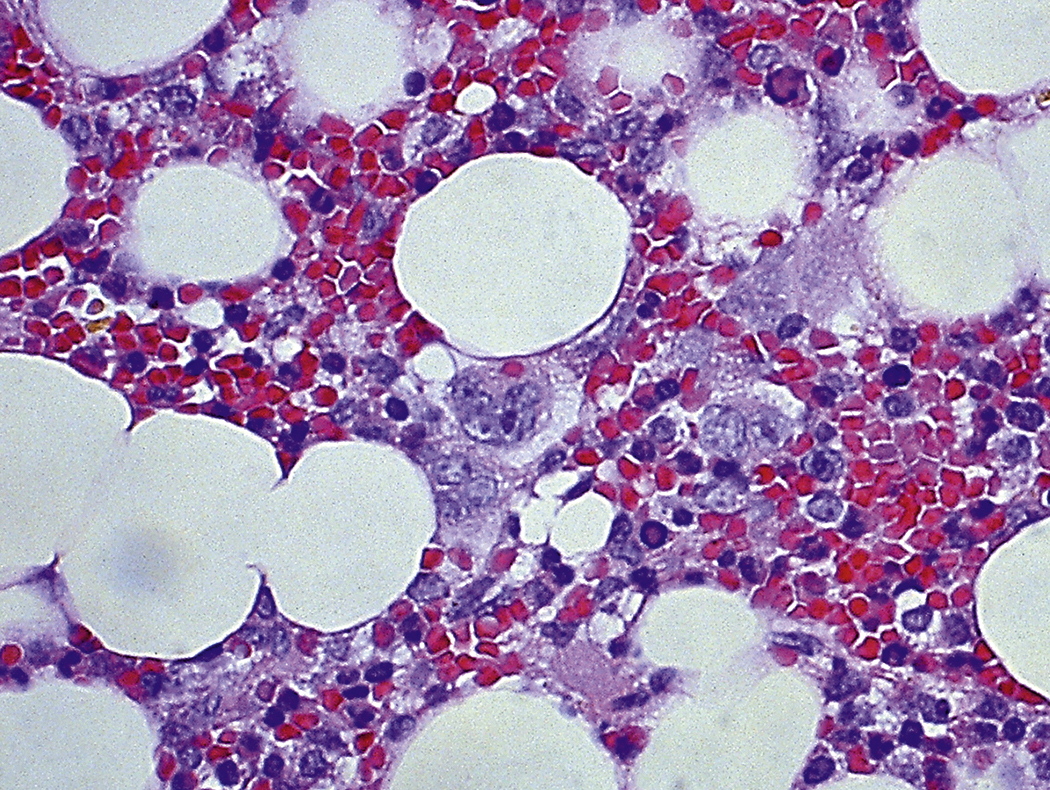

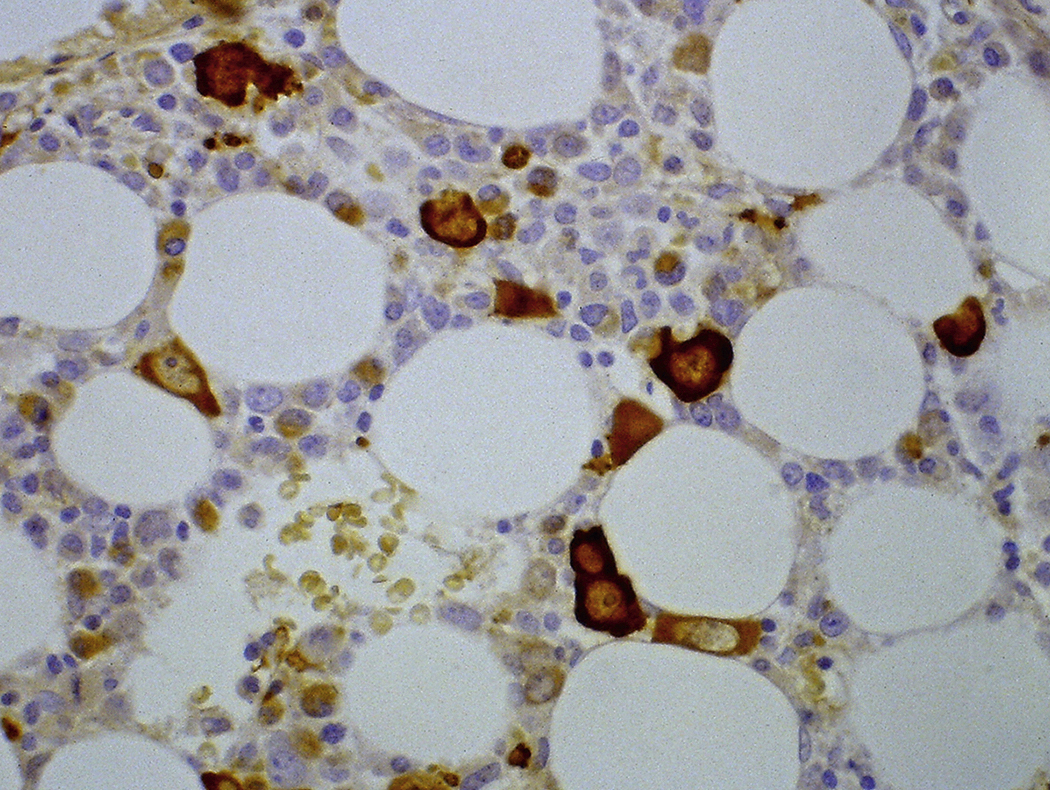

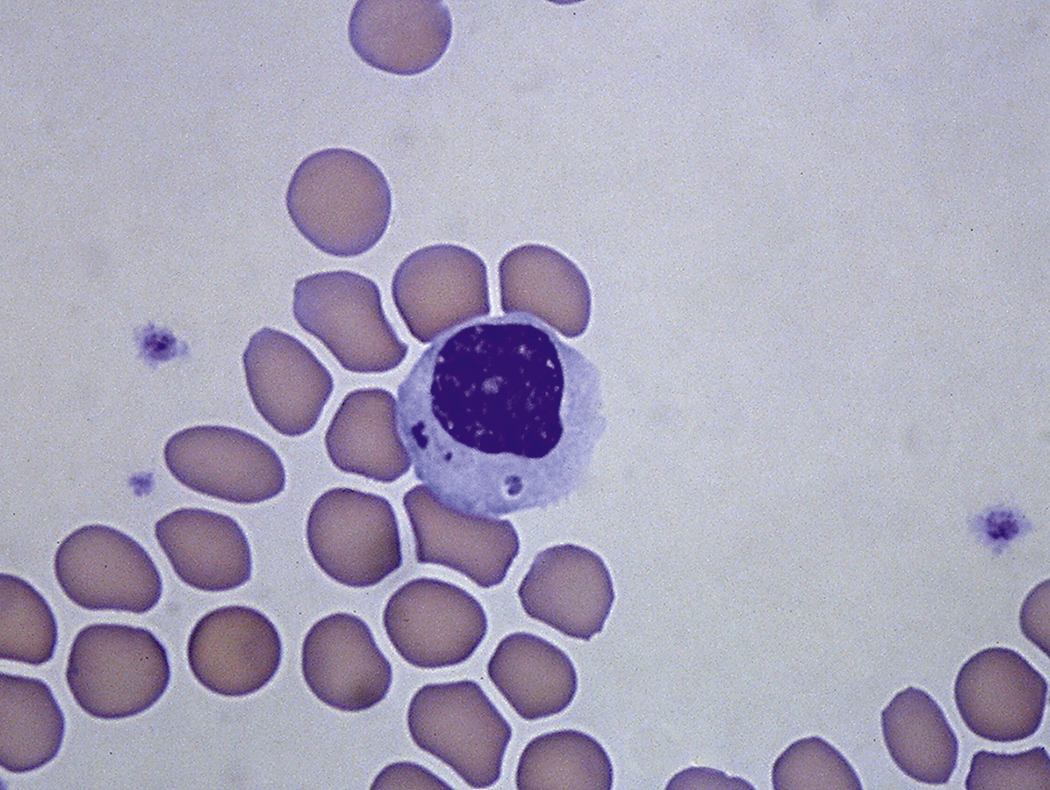

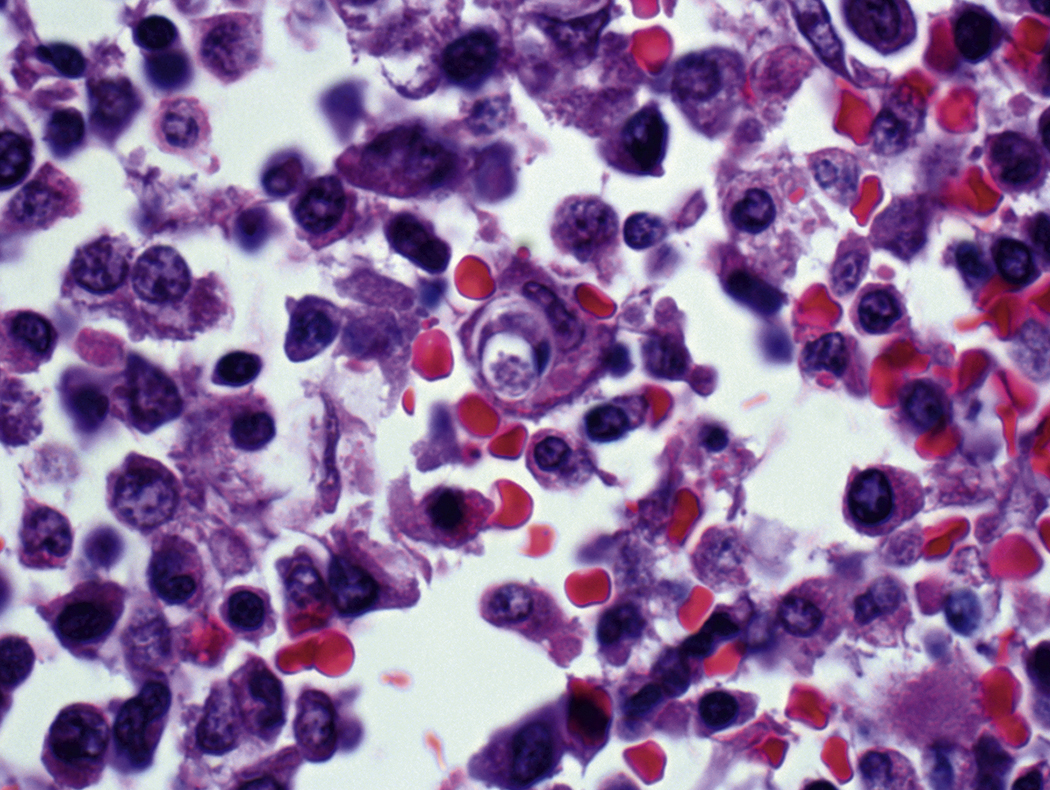

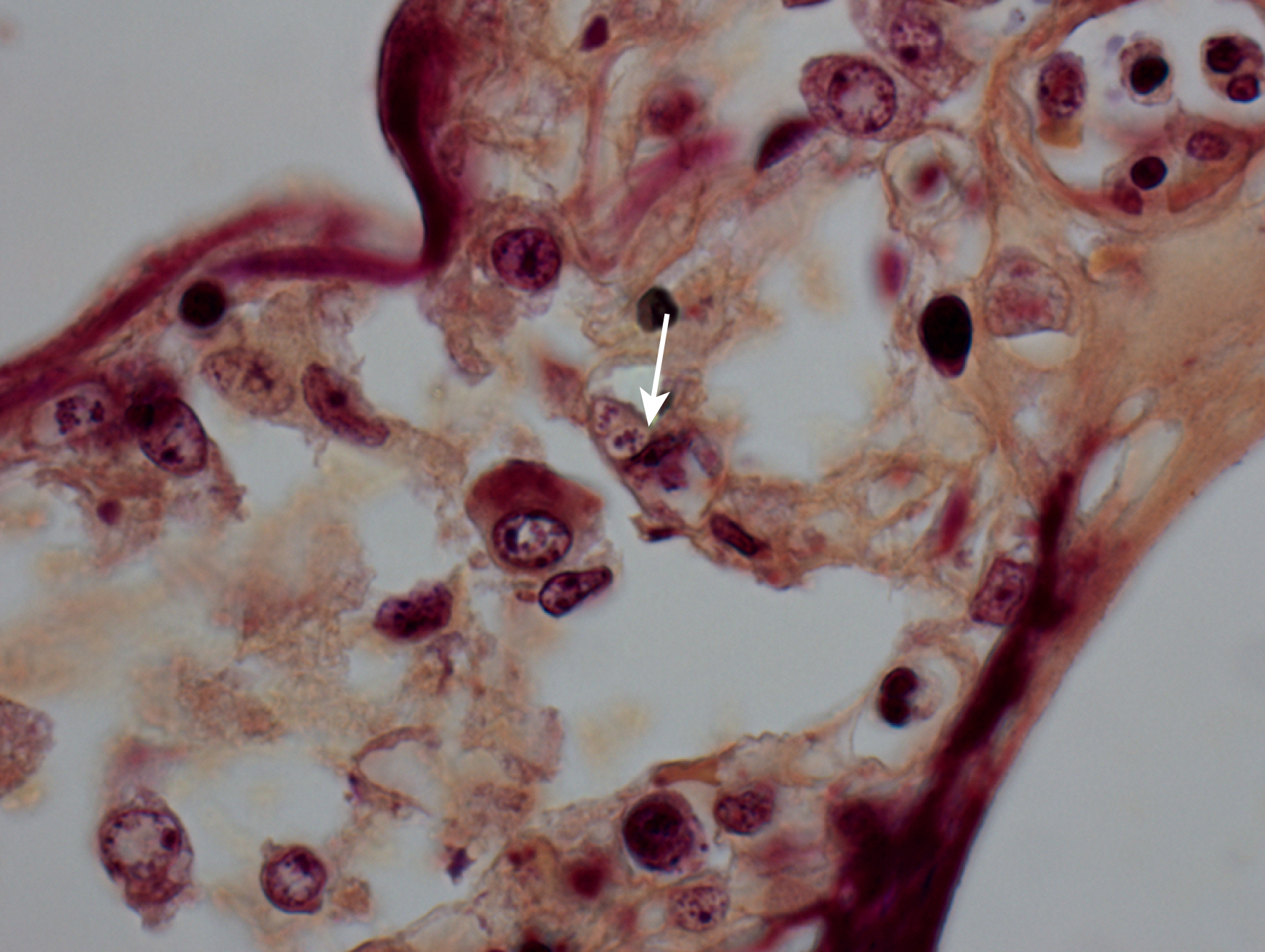

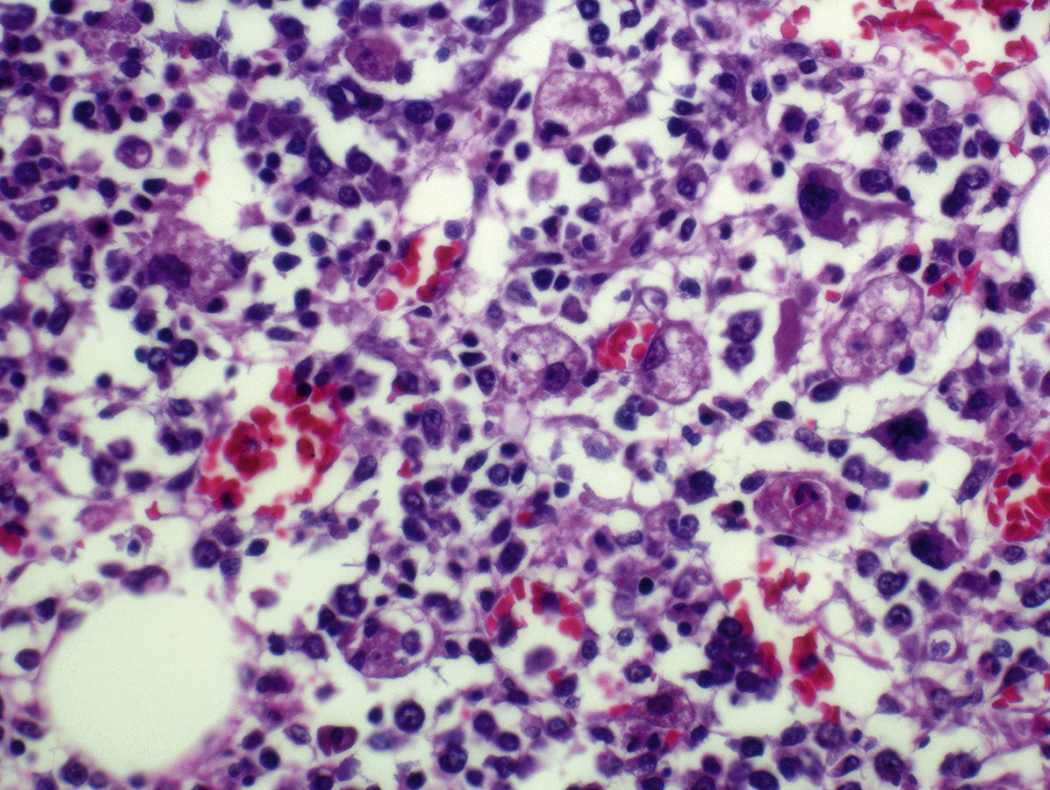

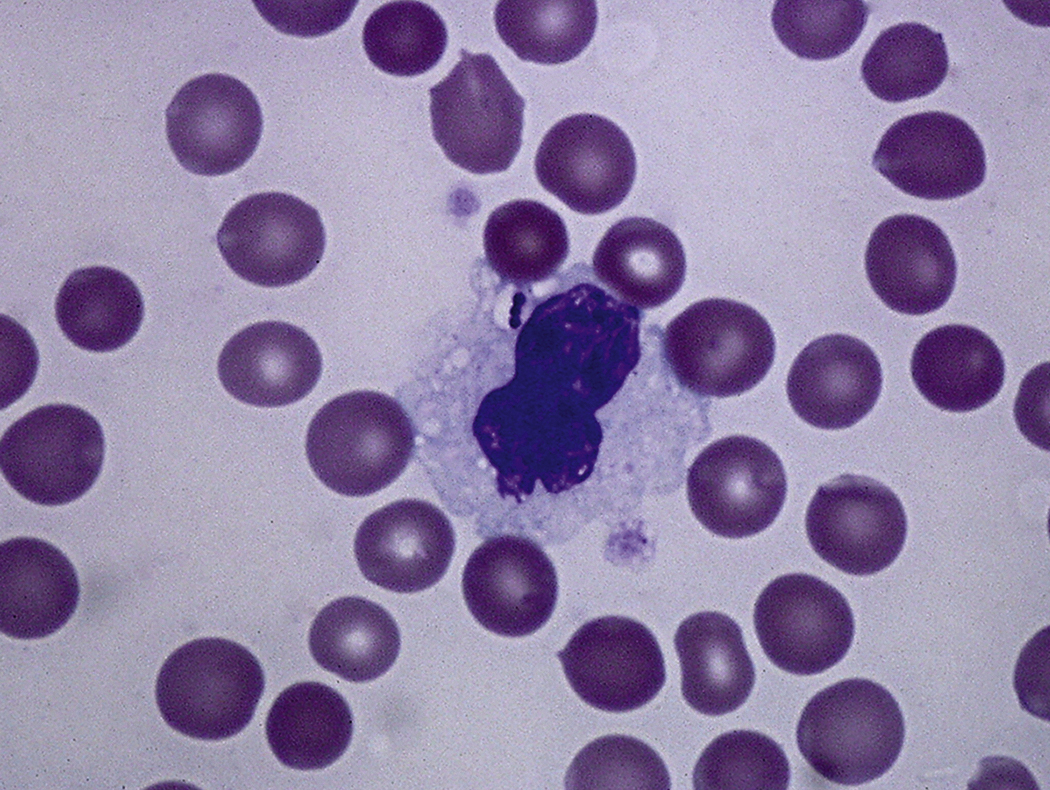

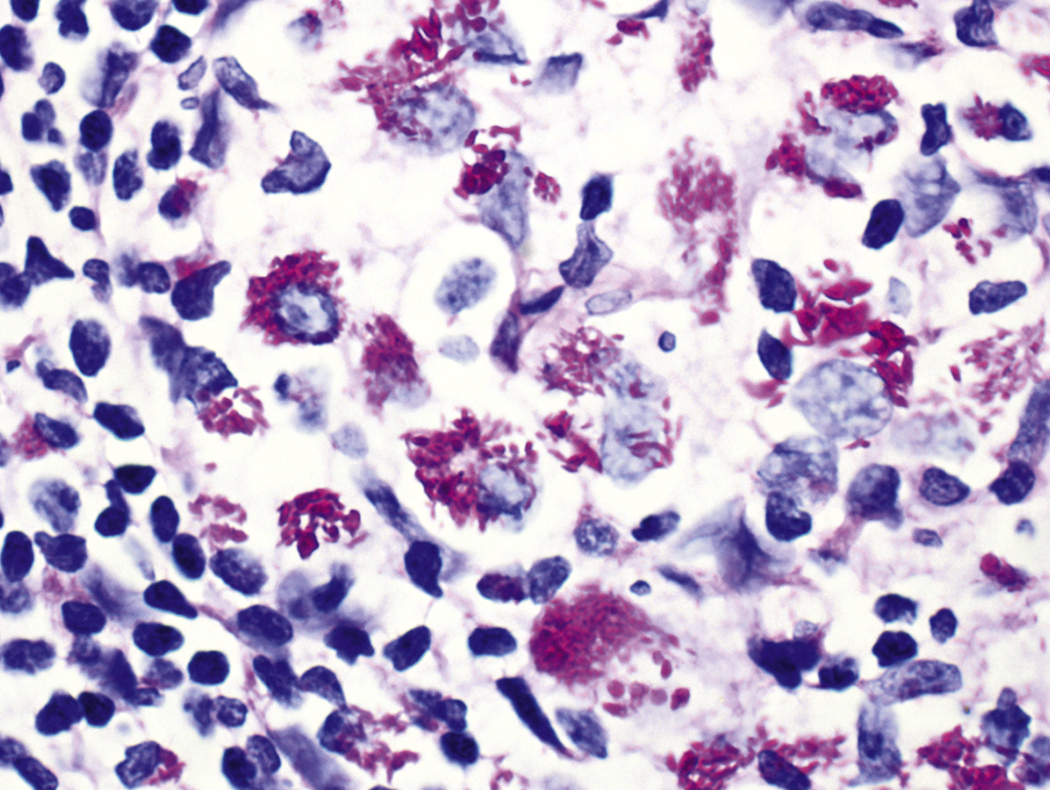

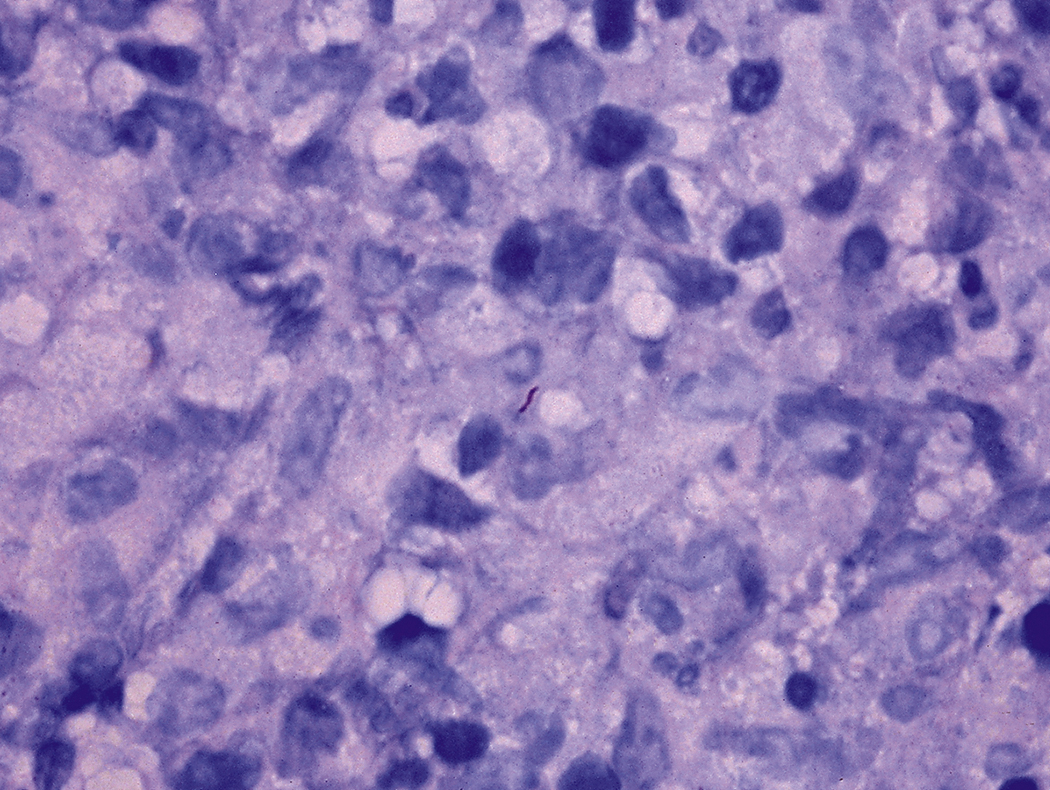

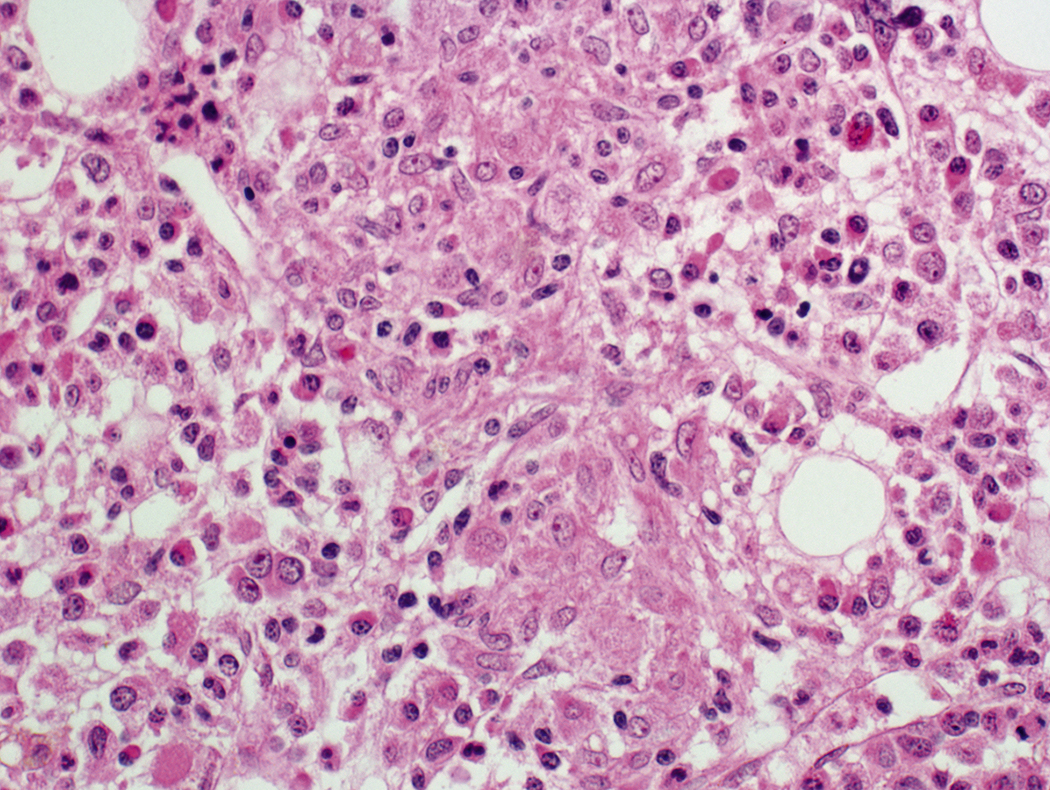

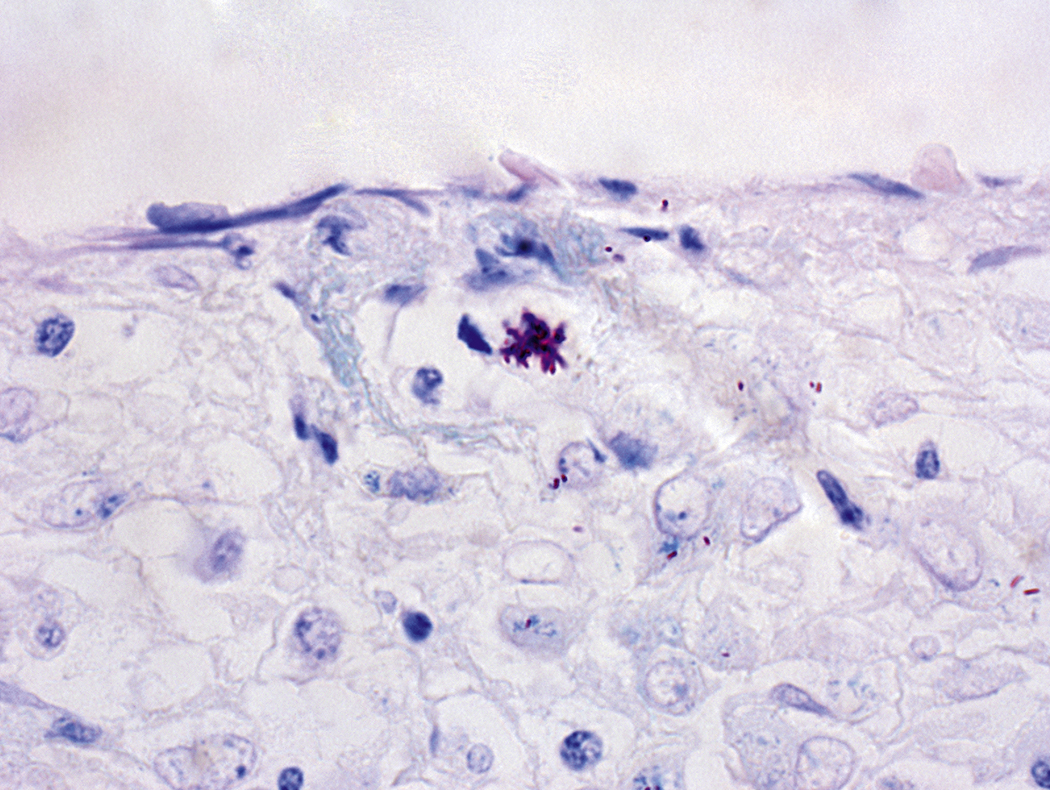

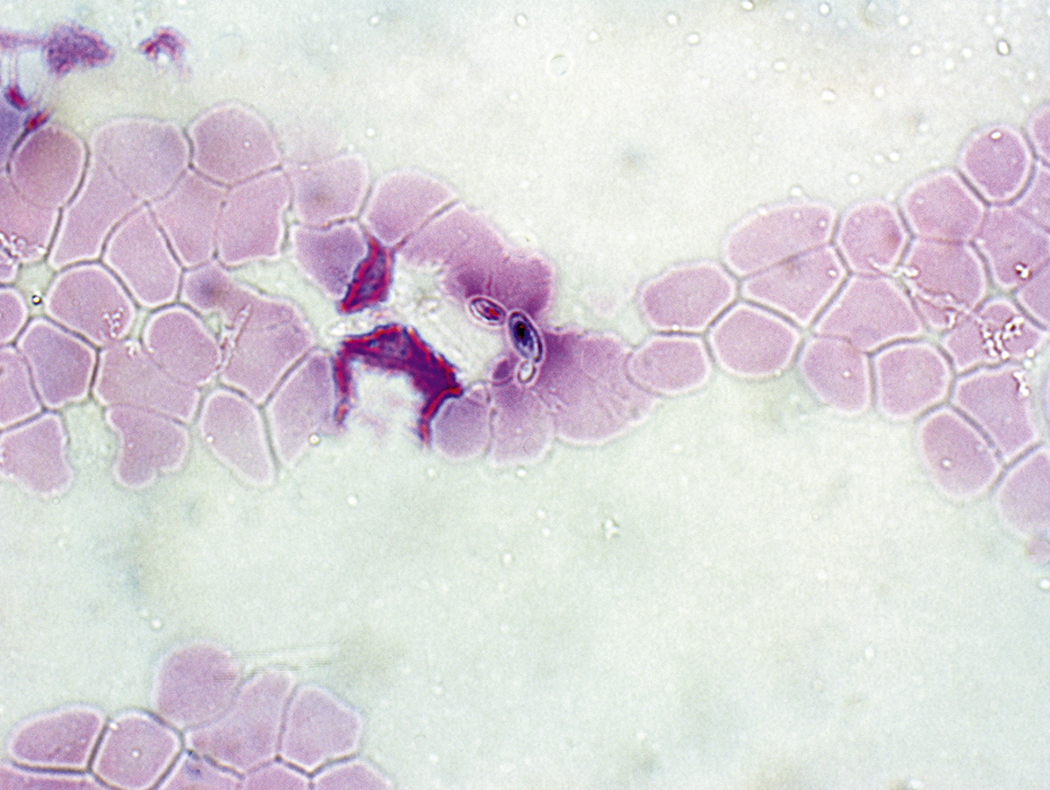

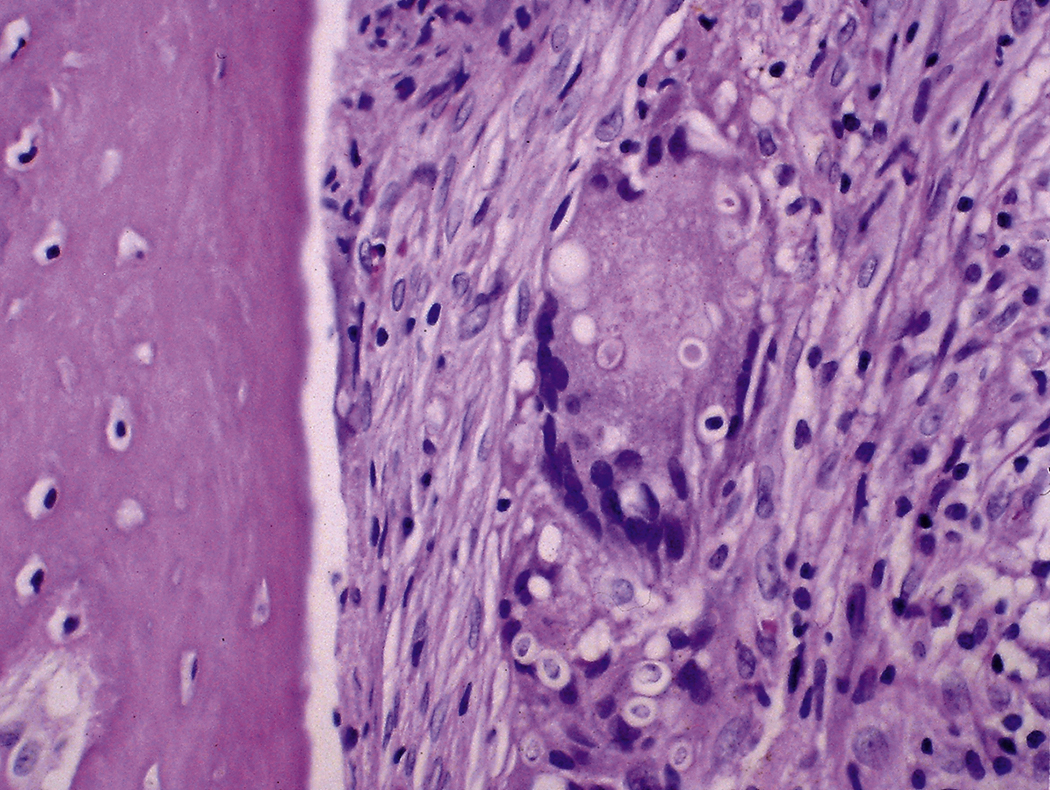

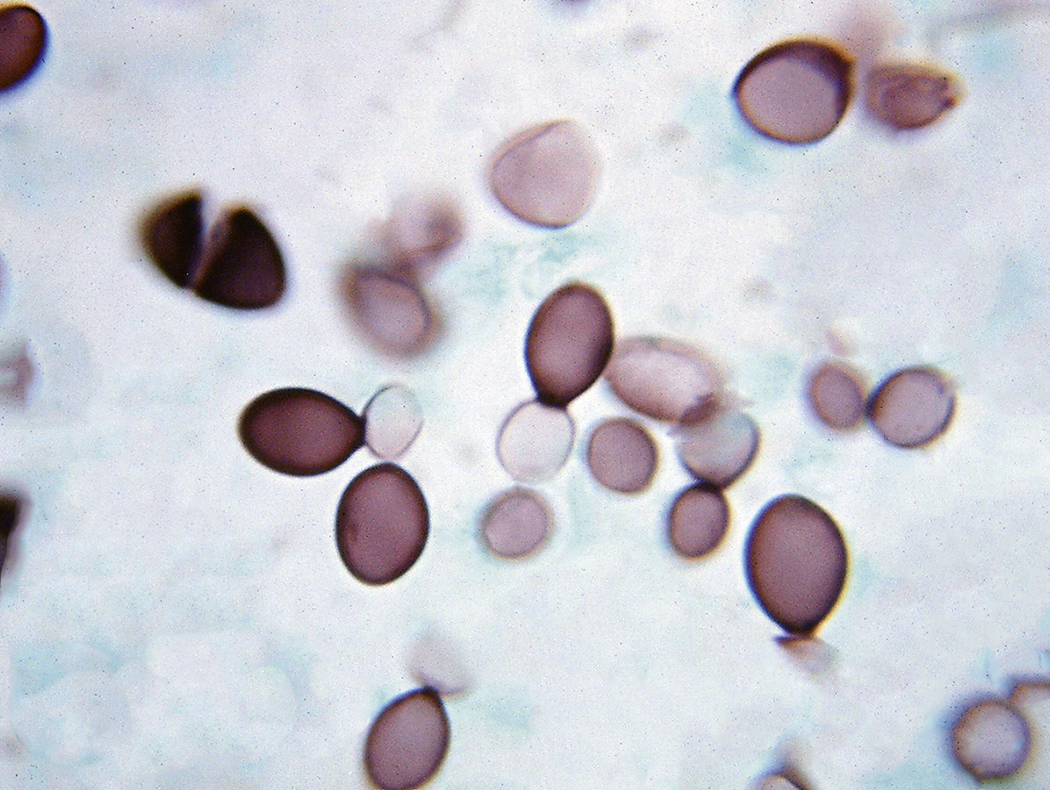

Certain viral infections can cause cytopathic changes in blood cells or changes in the maturation of blood cells. The nuclear or cytoplasmic inclusions of some viruses, particularly the herpesviruses, are visible by light microscopy. The most easily identified cytopathic changes are those of cytomegalovirus (CMV) ( Fig. 17.1 ). Nonspecific findings in bone marrow of CMV-infected patients may include myeloid and megakaryocytic suppression, hemophagocytosis, granulomas, or lymphoid aggregates; atypical lymphocytosis similar to that seen in infectious mononucleosis may be seen in peripheral blood. Circulating CMV-infected endothelial cells may sometimes be present at the feathered edge of a peripheral smear. Primary Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection causes large atypical lymphocytes in peripheral blood that are the origin of the term “infectious mononucleosis.” The bone marrow of EBV-infected patients may show focal lymphocytosis or fibrin ring granulomas. Human parvovirus B19 replicates in late erythroid precursor cells in bone marrow, resulting in giant pronormoblasts ( Figs. 17.2–17.4 ). An occasional pronormoblast may contain an eosinophilic inclusion that displaces the nuclear chromatin to the periphery and may contain cytoplasmic vacuoles. Early in human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection, the bone marrow may be hypercellular but becomes hypocellular in advanced disease and following therapy. Other findings in HIV-infected patients may include increased plasma cells, scattered macrophages, dysplastic hematopoietic cells, fibrosis, lymphoid hyperplasia, or proliferation of immunoblasts. The peripheral blood findings of paroxysmal cold hemagglutination (red blood cell agglutination and erythrophagocytosis by neutrophils) may be seen in a variety of viral (e.g., varicella, measles, mumps, and upper respiratory) and bacterial (e.g., syphilis and Haemophilus influenzae ) infections.

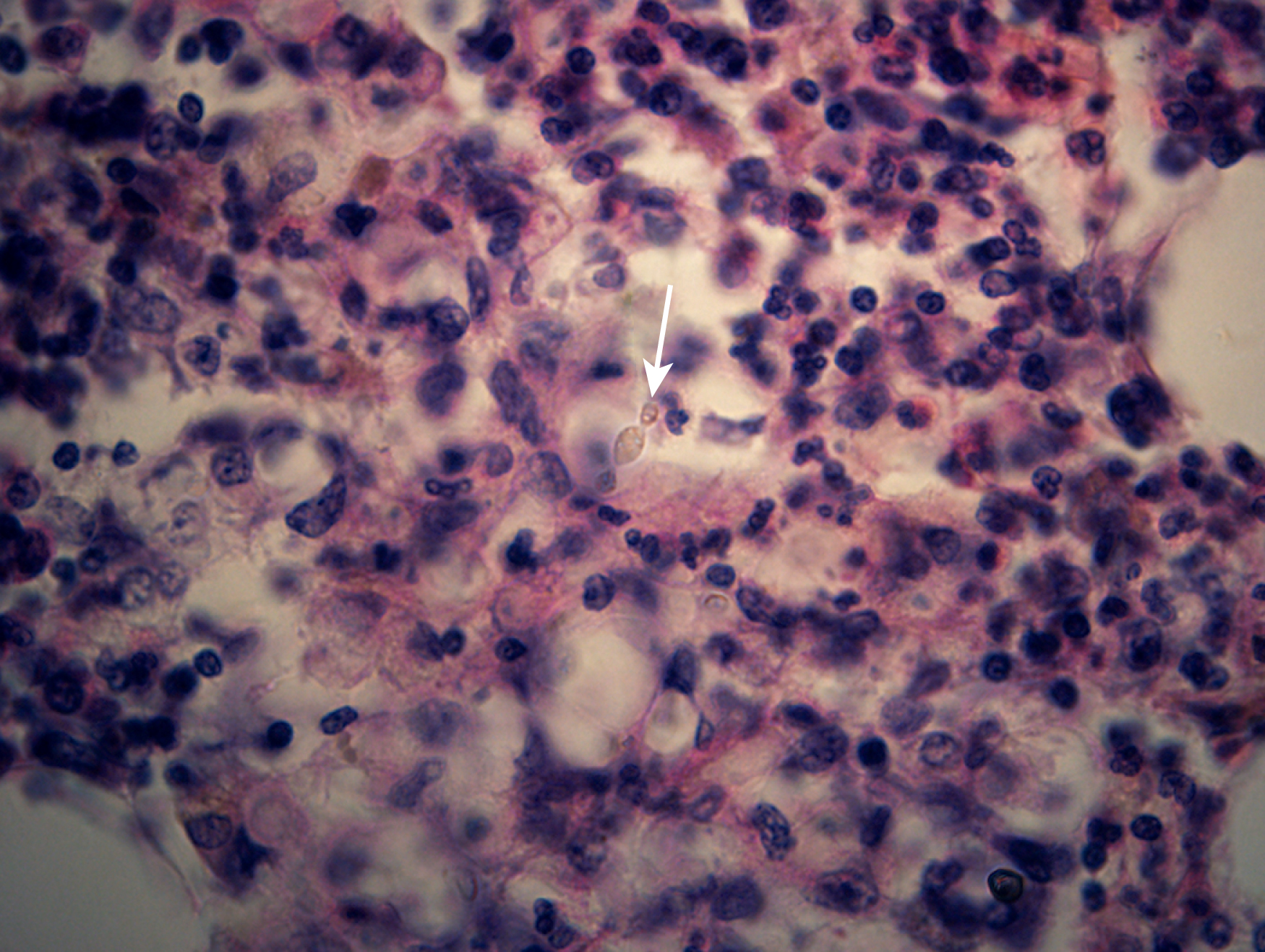

Bacterial Infections

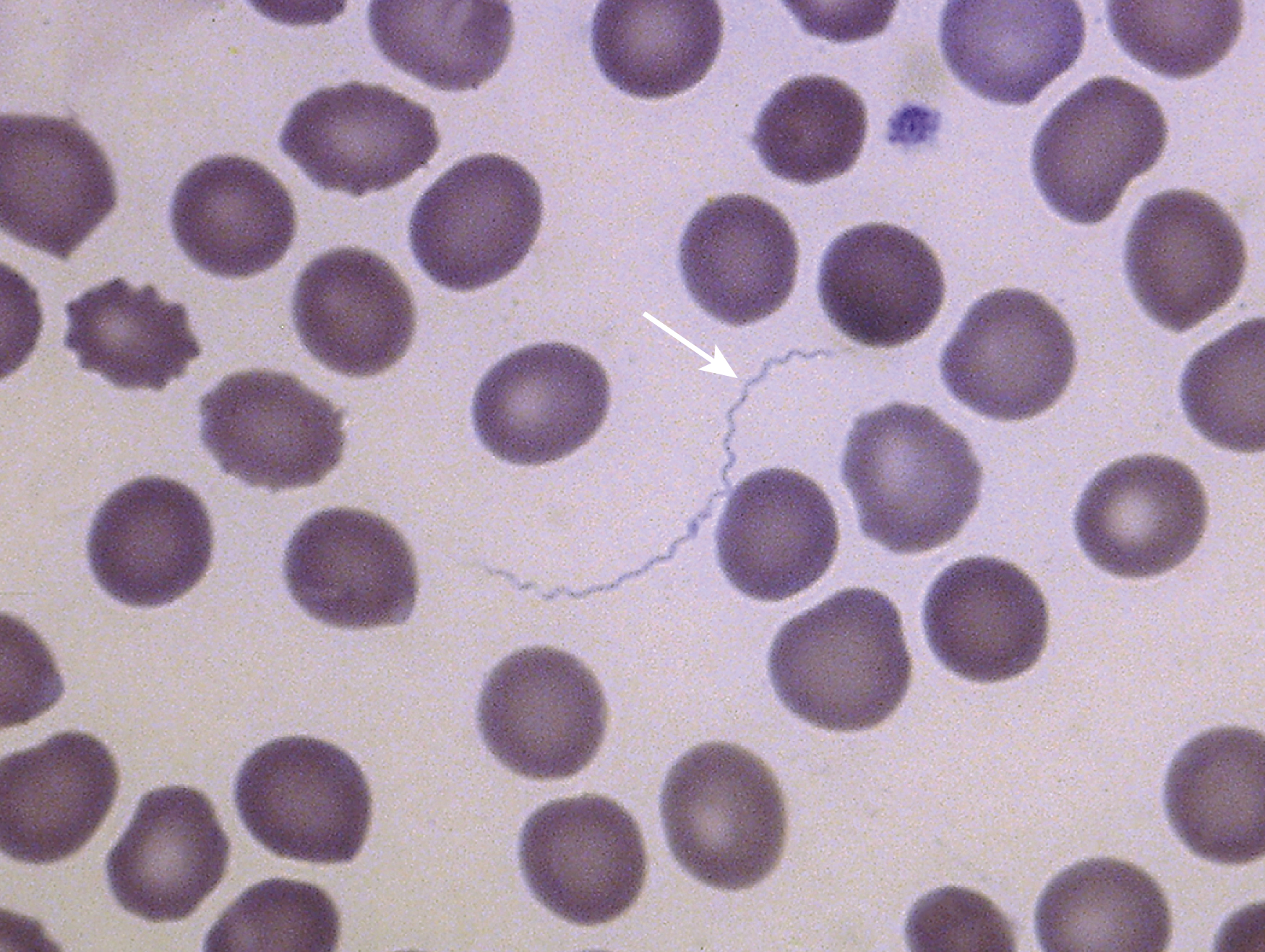

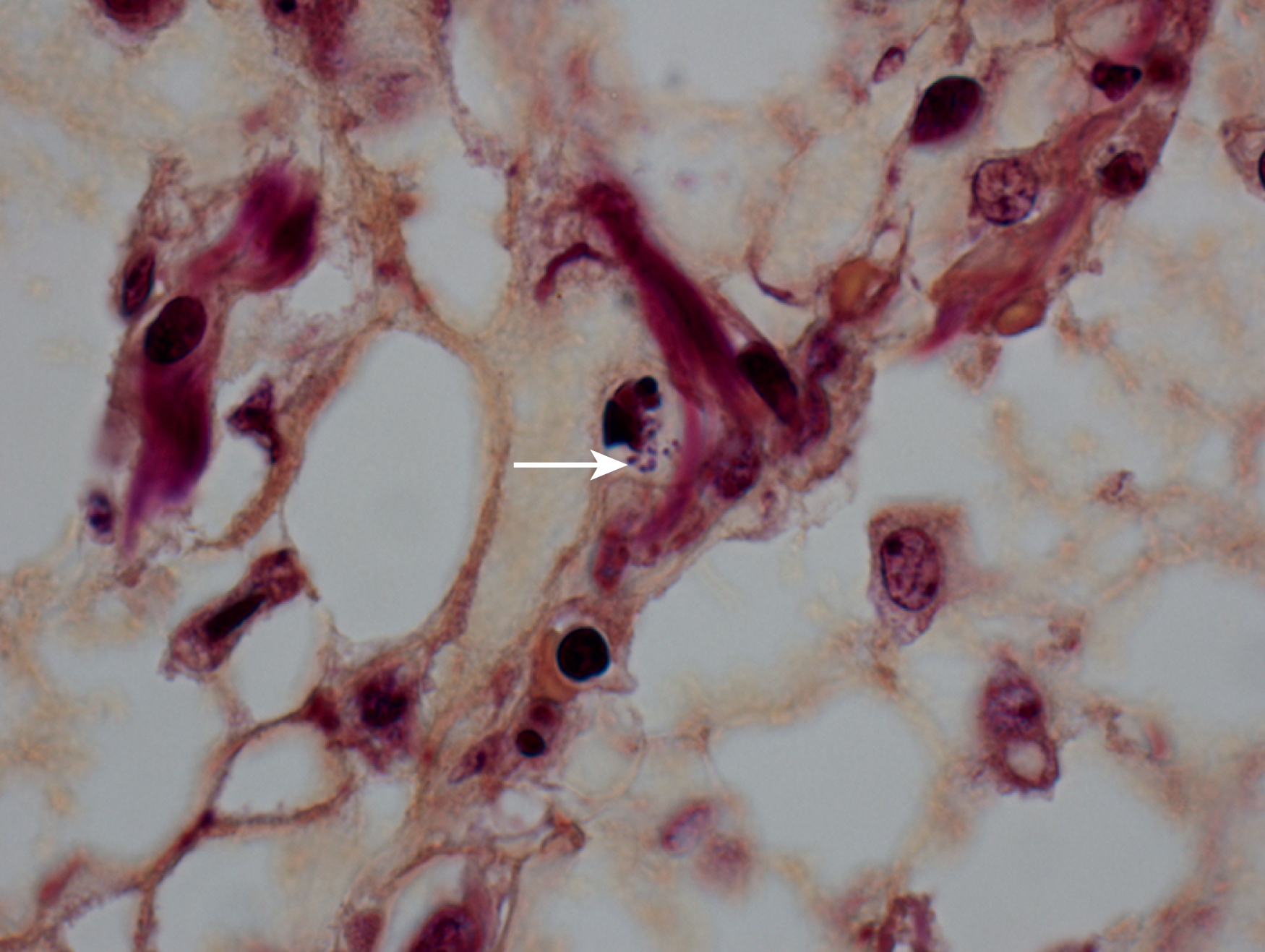

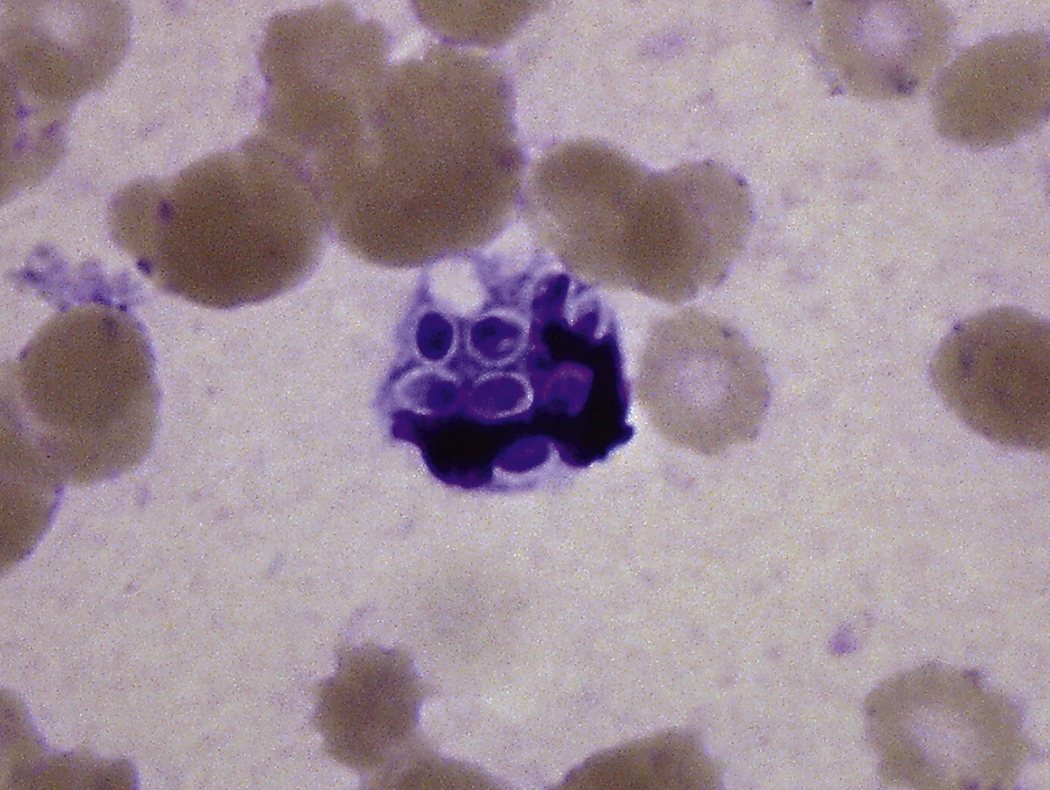

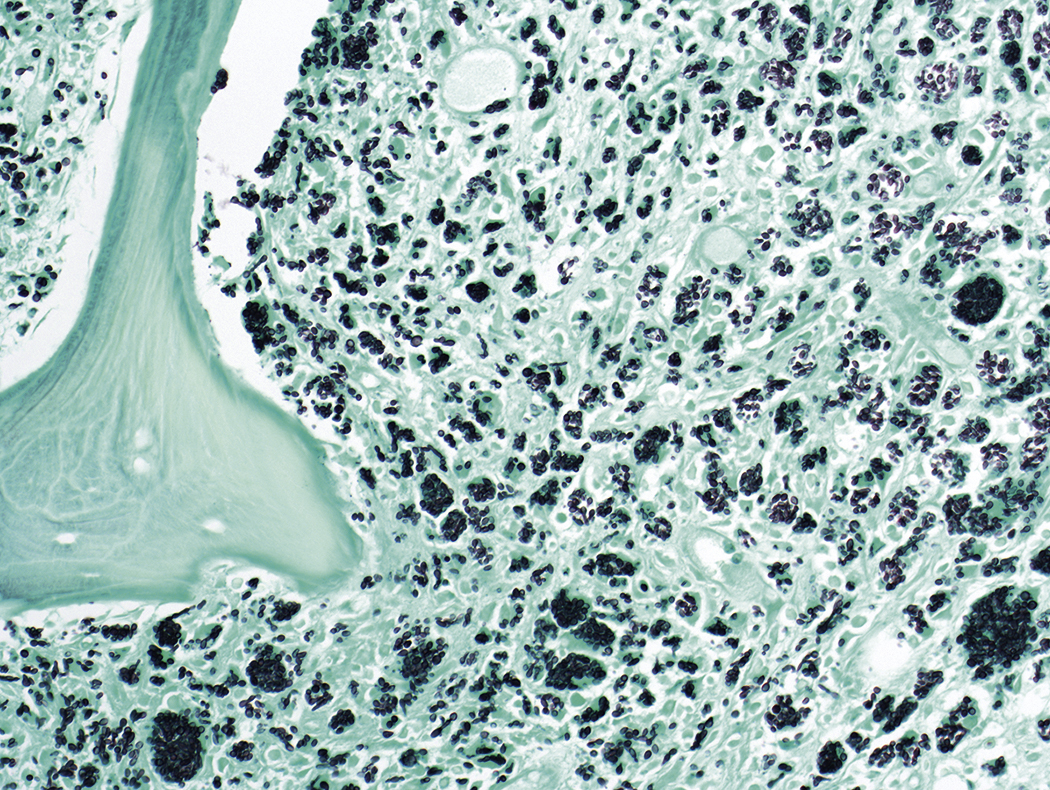

The finding of bacteria in peripheral blood or a bone marrow specimen often indicates a serious infection such as sepsis ( Figs. 17.5–17.17 ). Gram-positive cocci or rods may be found extracellularly or intracellularly within white blood cells in peripheral blood ( Fig. 17.12 ). Because bacteria are generally present in low concentrations in peripheral blood, detection may be improved by performing a Gram stain on a smear of the buffy coat. The specific identification of these microorganisms requires correlation with microbiologic cultures. There are some bacteria, however, whose appearance in peripheral blood is pathognomonic ( Table 17.1 ), such as Borrelia species ( Fig. 17.5 ), Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Ehrlichia species, which are obligate intracellular gram-negative bacteria ( Figs. 17.6–17.11 ); Tropheryma whipplei ( Fig. 17.13 ); and mycobacteria ( Figs. 17.14–17.17 ).

| Species | Disease | Morphologic Features |

|---|---|---|

| Borrelia recurrentis, Borrelia duttonii , and Borrelia crocidurae ( Fig. 17.5 ) | Relapsing fever | Extracellular spirochetes |

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (formally human granulocytic ehrlichiosis) | Inclusions in granulocytes in peripheral blood |

| Ehrlichia chaffeensis ( Figs. 17.6–17.11 ) | Human monocytic ehrlichiosis | Inclusions in monocytes in peripheral blood |

| Ehrlichia ewingii | Granulocytic disease in immunocompromised patients | Inclusions in granulocytes in peripheral blood |

| Tropheryma whipplei ( Fig. 17.13 ) | Whipple disease | Foamy bone marrow macrophages containing periodic acid–Schiff-positive, diastase-resistant bacteria |

| Mycobacterium species ( Figs. 17.14–17.17 ) | Tuberculosis and nontubercular mycobacteriosis | Acid-fast bacilli in bone marrow macrophages or bacilli within necrotizing granulomas |

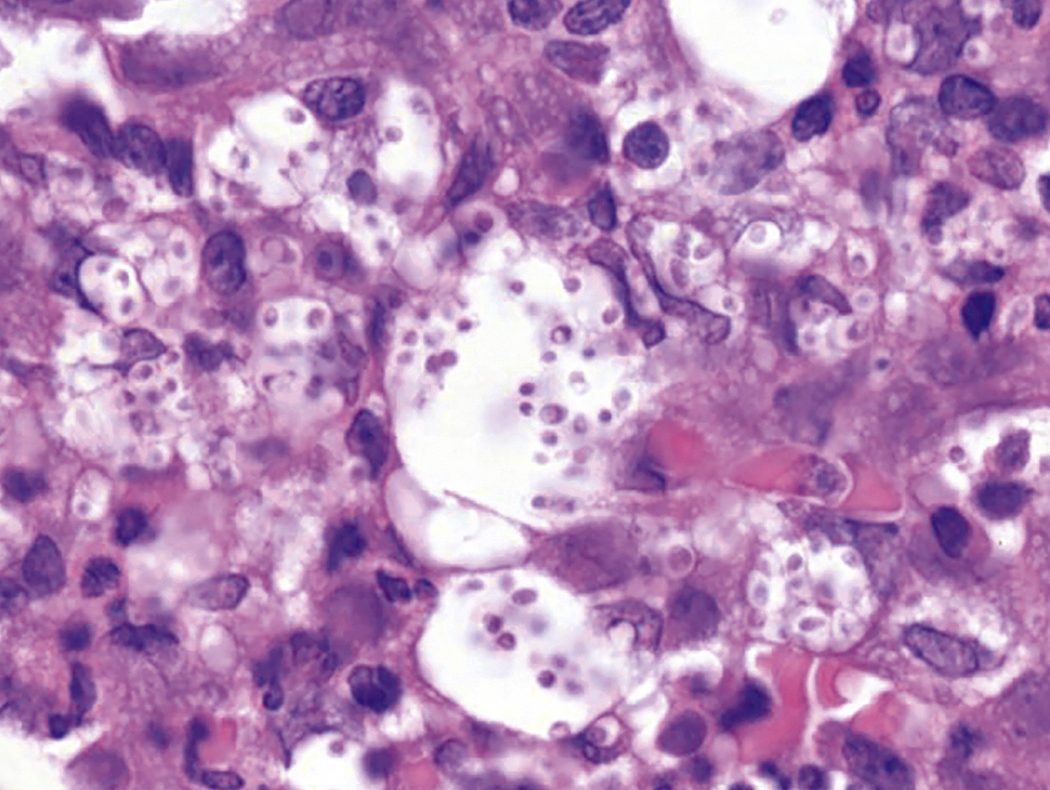

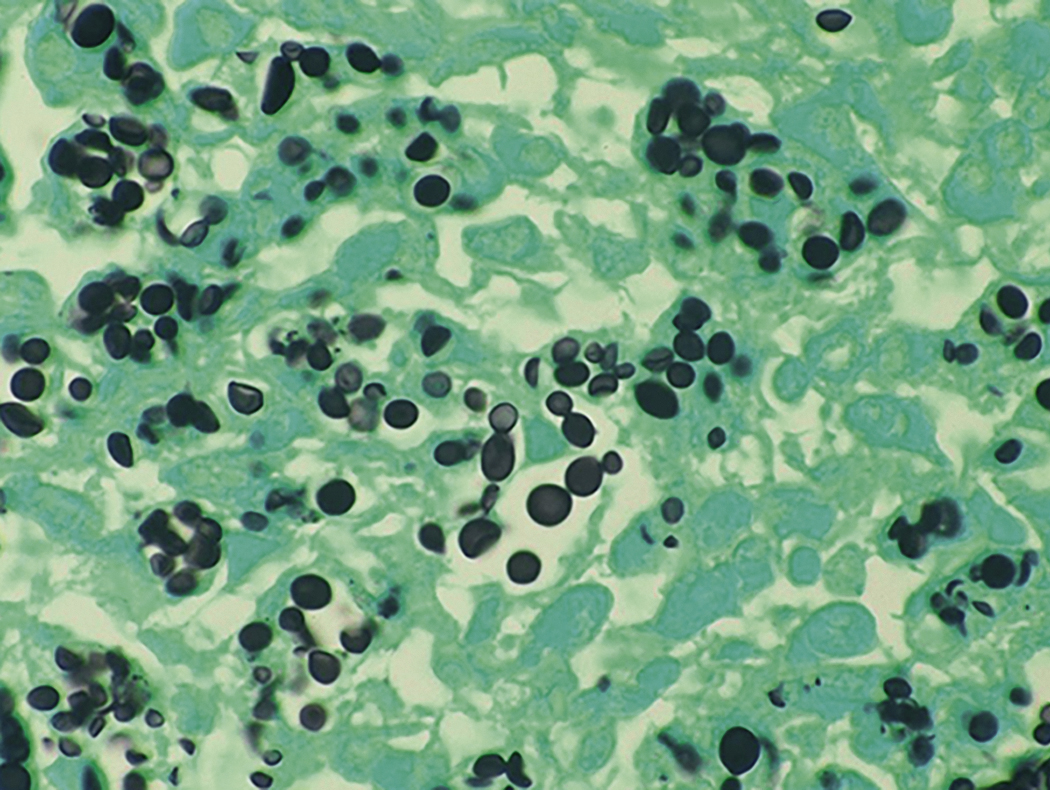

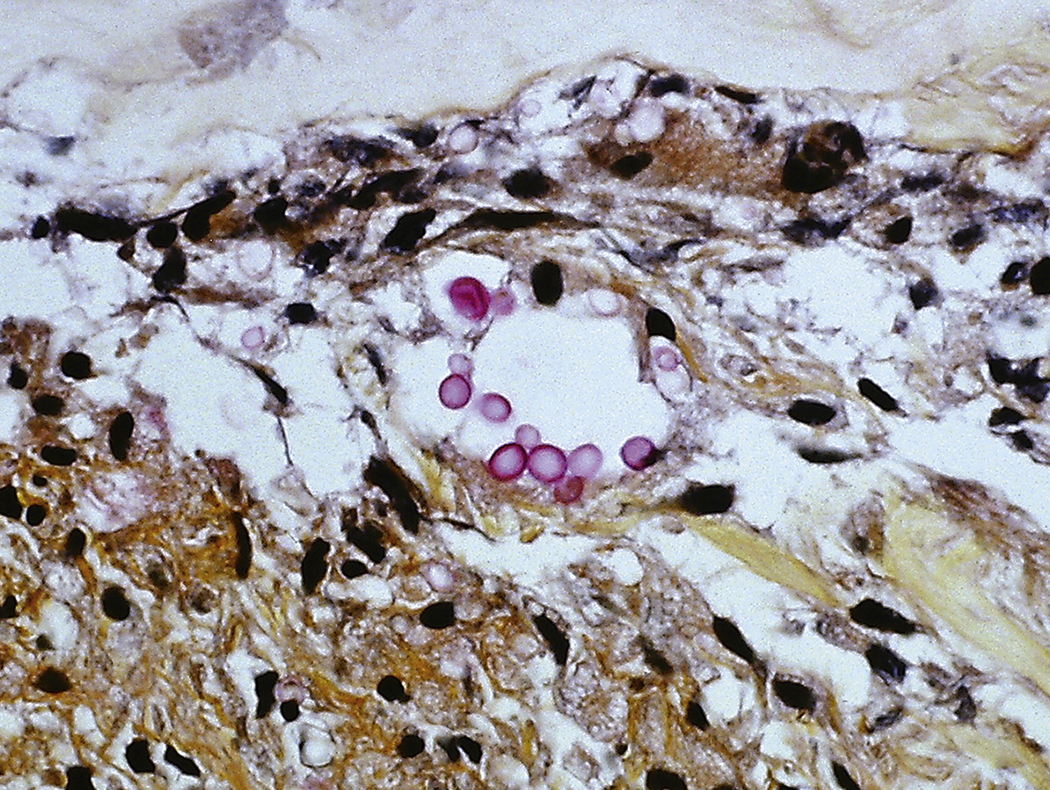

Fungal Infections

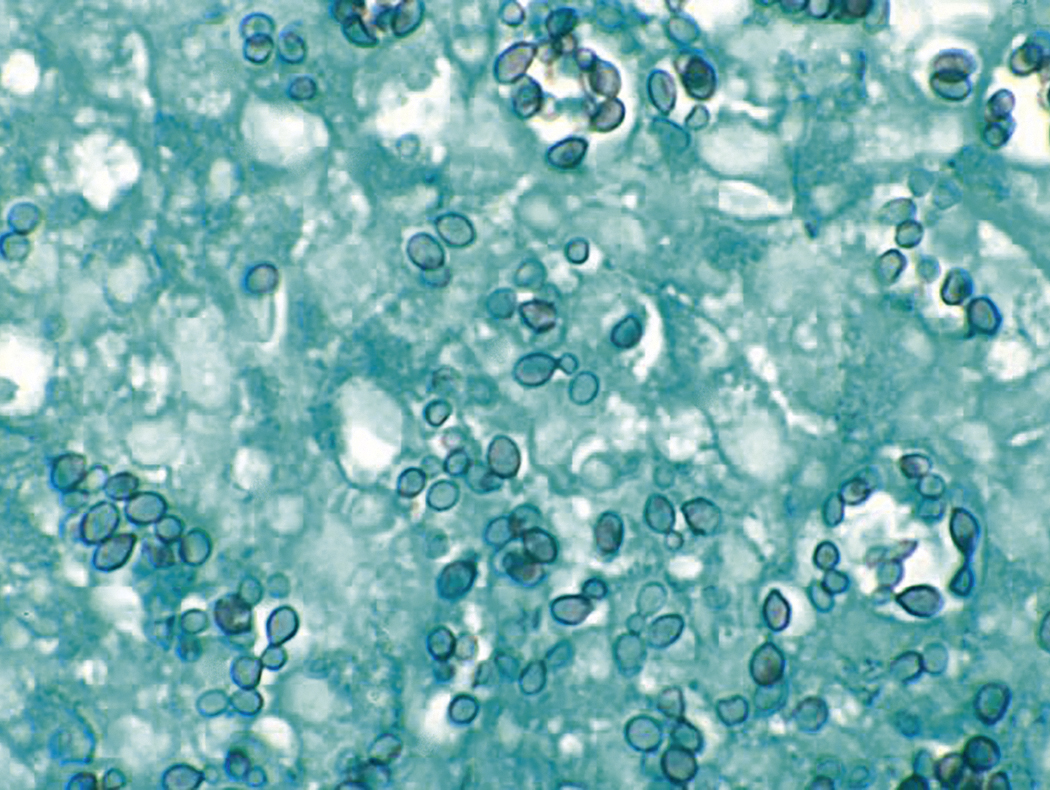

Like bacteria, fungi in peripheral blood or bone marrow often indicate a serious infection ( Figs. 17.18–17.29 ). Candida species are the fungal species most commonly encountered in peripheral blood smears ( Figs. 17.18 and 17.19 ). Any fungus that causes systemic infection, especially in immunocompromised patients, can be seen in bone marrow specimens; examples include Histoplasma species ( Figs. 17.20–17.25 ) and Cryptococcus species ( Figs. 17.26–17.29 ).

Parasitic Infections

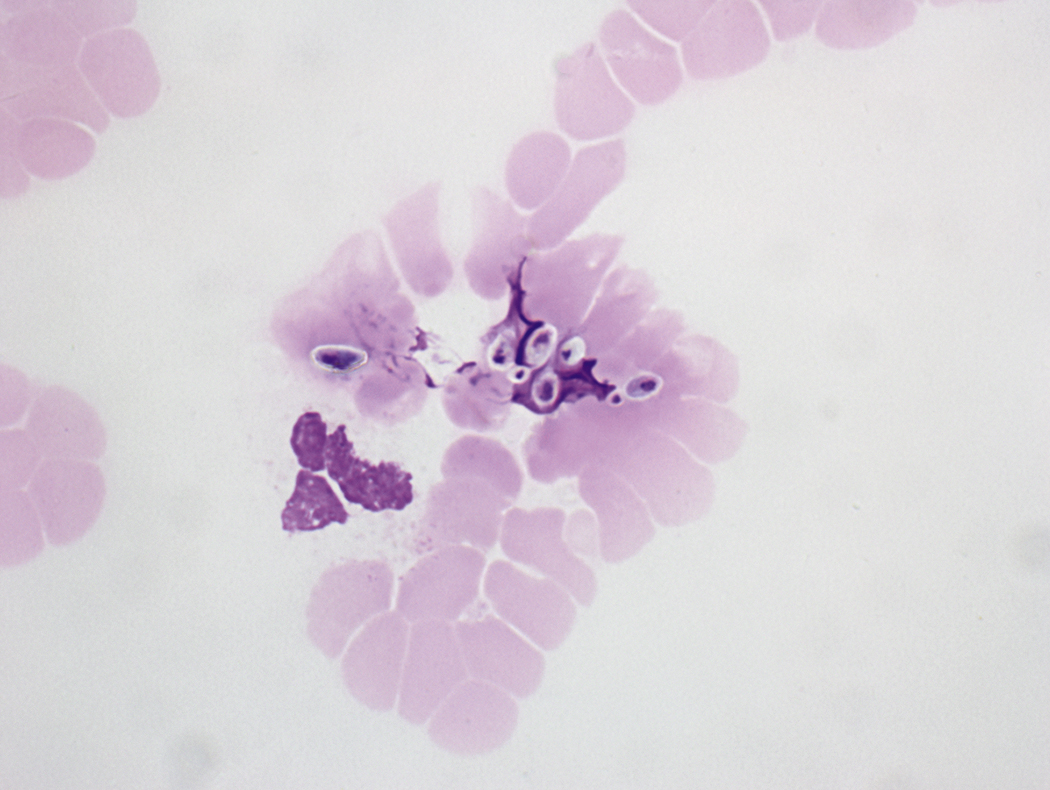

The most common protozoal infection in peripheral blood is malaria. All of the stages of Plasmodium found in peripheral blood are composed of chromatin and cytoplasm, may or may not contain pigment, and are present as trophozoites (growing forms), schizonts (dividing forms), or gametocytes (sexual forms). Morphologic features that allow determination of species are summarized in Table 17.2 . Trophozoites range from small young ring forms to mature forms with chromatin that is still undivided. Young ring forms, which are often indistinguishable among species, may be observed in all four types of malaria. In immature schizonts, division has just begun. In mature schizonts, division of chromatin and cytoplasm is complete, pigment is clumped in a single mass, and cytoplasm is separated into distinct masses. The number of merozoites (asexual components of schizonts) in a mature schizont varies considerably among the species. Although each Plasmodium species has a diagnostic form, a given specimen may not demonstrate all of the classic features of a single species, and considerable overlap occurs ( Figs. 17.30–17.50 ). Therefore, the most useful diagnostic approach combines comparison and exclusion. Determination of the species of Plasmodium involves observation of the degree of parasitemia, the size and shape of parasitized red blood cells, and the morphologic features of the parasite. If there are only a large number of ring trophozoites, the species is most likely P. falciparum ( Fig. 17.30 ). If only a few ring trophozoites are observed, it may not be possible to determine the species, and the specimen should be designated as “malaria, species undetermined.” In falciparum malaria, parasitemia may be 40% or higher; in infections with the other species, parasitemia is usually less than 2%. Only P. falciparum malaria has gametocytes that are elongate ( Figs. 17.32 and 17.33 ). The size of the parasitized red blood cells is a useful feature. If the parasitized red blood cells are enlarged, it is probably P. vivax or P. ovale and not P. malariae (unless it is a mixed infection). If many of the enlarged red blood cells are oval or fimbriated, Plasmodium ovale infection is most likely ( Fig. 17.38 ). Fewer numbers of oval or fimbriated red blood cells suggests Plasmodium vivax infection. Although all four species of Plasmodium can have thin band trophozoites, only those of Plasmodium malariae are large enough to occupy 50% to 75% of a normal-sized or small red blood cell ( Fig. 17.42 ). Infections by mixed species should be diagnosed cautiously. Thick peripheral blood smears are generally more useful in detecting malaria than in determining species ( Fig. 17.47 ).

| Species | Red Blood Cells | Multiply Infected Red Blood Cells | Diagnostic Form | Number of Merozoites in Mature Schizont | Stippling | Gametocyte | Trophozoite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmodium falciparum ( Figs. 17.30–17.33 ) | Normal size | Frequent | Crescent-shaped gametocytes | 8–24 (more if multiply infected red blood cell) | Rare coarse Maurer dots | Crescent-shaped | Small ring forms, double chromatin dots, marginal forms |

| Plasmodium vivax ( Figs. 17.34–17.37 ) | Enlarged | Occasional | Ameboid trophozoite in enlarged red blood cell with Schüffner dots | 16 (12–24) | Schüffner dots | Round | Tenuous or ameboid forms, large, occasional double chromatin dots |

| Plasmodium ovale ( Figs. 17.38–17.41 ) | Enlarged, oval, fimbriated | Occasional | Oval, fimbriated enlarged red blood cell | 8 (4–16) | Schüffner dots | Round or oval | Compact, large, slightly ameboid, occasional double chromatin dots |

| Plasmodium malariae ( Figs. 17.42–17.46 ) | Normal size or small | Rare | Large broad band trophozoite | 8 (6–12) | Rare Ziemann dots | Round | Band forms, basket forms, rare double chromatin dots |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree