2Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Spain

- Advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and tuberculosis are chronic infections that are commonly associated with wasting.

- Reduced nutrient intake is the main cause of wasting, although metabolic disturbances may promote lean-tissue loss.

- Increasing nutrient intake is the key to treatment, although pharmacological management approaches may also sometimes be helpful.

- Anti-HIV drug treatment is frequently complicated by body fat changes and metabolic disturbances.

- Acute infections such as malaria and acute infectious diarrhoea have important effects on nutritional status, especially in children, and are an important cause of death in developing countries.

- Malnutrition increases the risk of malaria.

- Rehydration therapy, achieved using the World Health Organization (WHO) rehydration mixture or similar solution, is the key to management of acute infectious diarrhoea.

21.1 Introduction

Chronic infections often have profound effects on nutritional status. Two chronic infections are of particular importance in terms of global morbidity and mortality in the early twenty-first century: tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. The interaction between malnutrition and tuberculosis has long been recognised, although there has been little scientific research in this area. This is in contrast with HIV infection, a relatively new infection, where intense research efforts in the last 25 years have resulted in a body of knowledge about the effects of infection on nutrition and metabolism and the treatment of wasting, which far exceed the existing knowledge accumulated for any other infectious disease. This chapter will therefore focus on HIV infection, and to a lesser extent on tuberculosis, in order to outline the existing knowledge about the nutritional issues accompanying chronic infections. Many of the principles probably apply to other infectious diseases.

The effects of acute infection on host nutrition and metabolism are similar to those of many other stress conditions, and are largely independent of the causative pathogen. The interaction between nutrition and acute infection is especially important in developing countries, where pre-existing malnutrition may increase the frequency and severity of acute infections, and certain acute infections may precipitate malnutrition. Acute gastroenteritis and malaria will be described in this chapter, as they are extremely common infections in the developing world and are both good examples of the infection–nutrition interaction.

Infectious diseases are extremely heterogeneous in their clinical presentation, although a number of nutritional features (such as anorexia, catabolism, increased basal metabolic rate (BMR), decreased physical activity, and increased requirements for some micronutrients) are common to most of them. In addition to these general manifestations, there are other, more specific features of some infectious diseases that may have nutritional consequences. Examples include the requirement for special forms of nutritional support in patients with severe infections who require intensive care and mechanical ventilation; the oesophageal dilatation and dysmotility of Chagas’ disease; and the fluid and electrolyte disturbances of patients with severe gastrointestinal infections, such as cholera.

21.2 Human immunodeficiency virus infection

Transmission and epidemiology

HIV is transmitted by sexual intercourse (homosexual or heterosexual), by transfusion of infected blood or blood products, by needles contaminated with blood (usually in intravenous drug abusers who share needles, rarely in the context of accidental injury to healthcare workers), or vertically (i.e. from mother to baby in utero, intrapartum, or by breast milk). Whereas the principal mode of transmission in developed countries is sexual contact between men, the majority of infections worldwide are acquired by heterosexual transmission and vertical transmission.

The acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic looks set to be among the most devastating events in human history. There were estimated to be 34 million people living with HIV infection at the end of year 2010, more than 3 million of whom are children. There are approximately 2.7 million new infections and 2 million deaths from AIDS each year, thus placing HIV infection in the same league as the traditional scourges of tuberculosis and malaria as the principal infectious causes of mortality in global terms. The disease has decreased life expectancy by 20 years in some of the worst-affected countries.

Clinical features

The course of HIV infection can be divided into four stages. The seroconversion illness (stage I) occurs in 50–90% of patients at an average of 2–4 weeks following acquisition of infection. There follows an asymptomatic phase (stage II) without overt clinical manifestations, although active replication of virus and destruction of CD4 cells continues. This asymptomatic phase may last indefinitely in a small proportion (less than 5%) of patients, but will progress to symptomatic infection in the majority. The earliest indication of progression to immune failure and symptomatic disease is usually mucocutaneous conditions, such as oral candidiasis (thrush) and oral hairy leucoplakia. Persistent generalised lymphadenopathy is the first definitive condition to signify the end of the asymptomatic phase and its occurrence defines stage III disease.

With further depletion of immune function, patients become at risk of opportunistic infections and malignancies. When one of a defined set of indicator conditions develops (such as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis, or Kaposi’s sarcoma), the patient is deemed to have developed AIDS or stage IV disease. Until the recent advent of highly effective combination antiretroviral therapies, AIDS was invariably fatal within a few years. It has recently been recognised that HIV-infected patients are also at increased risk of a variety of diseases in addition to the traditional AIDS-defining conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and bone disease.

Treatment of HIV disease

The therapeutic approach may be divided into prevention of disease progression and treatment of complications that arise. Considerable progress in the development and utilisation of antiretroviral drugs has been made in the last 15–20 years. Nucleoside analogues, which block the action of the HIV reverse transcriptase enzyme and drugs that inhibit the HIV protease enzyme and the processes of viral fusion and integration have been developed and have a powerful effect in the treatment of HIV. Combination of a protease inhibitor (or alternative drug) with two nucleoside analogues is now regarded as the standard of care in developed nations. This highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has been shown to be effective in halting and even reversing the progression of HIV disease. Widespread adoption of HAART in developed nations has markedly decreased the population rates of progression from asymptomatic HIV disease to AIDS and the rate of death from AIDS-related illnesses. A retrospective cohort study of nearly 8000 patients in France demonstrated drops in hospitalisation days by 35%, new AIDS cases by 35%, and deaths by 46% within 1 year following the introduction of HAART into routine usage.

In cases where severe immune compromise has already occurred, prophylactic antibiotics can be used to prevent opportunistic infections such as PCP and Mycobacterium avium infection. Most of these agents can be discontinued after a period on effective antiretroviral therapy. In patients who present for the first time with an episode of acute opportunistic infection, antimicrobial treatment is initially directed towards overcoming the infection.

For patients living in settings where antiretroviral therapy is not universally available, the approach to therapy of HIV disease may be limited to the treatment of specific complications (especially tuberculosis) and prophylaxis of other infections where affordable agents are available.

Wasting in HIV infection

Definition of HIV wasting syndrome

Involuntary weight loss is a common feature of advanced HIV infection, and ‘HIV wasting syndrome’ is recognised as one of the conditions that can define a patient as having advanced disease or AIDS. The definition of HIV wasting syndrome is given in Box 21.1.

- HIV-associated wasting is largely a phenomenon of advanced HIV disease (AIDS).

- Wasting usually occurs in association with opportunistic infections.

- Reduced food intake is central to the pathogenesis of wasting.

- There are numerous causes of reduced food intake in HIV patients.

- Malabsorption is common, but is likely to act only as an exacerbating factor rather than the sole causative factor in wasting.

- Numerous metabolic derangements accompany HIV disease, but their role in wasting is unclear.

- Body-composition studies show preferential lean-tissue and body cell mass (BCM) loss, indicating that metabolic factors may have an influence.

- Hypogonadism contributes to BCM loss in a subset of patients.

Epidemiology of HIV wasting syndrome

Surveillance studies in the USA conducted in the early 1990s estimated that between 20 and 25% of patients who had AIDS developed wasting syndrome at some time during the course of their disease. In the late 1990s, the widespread use of HAART had a dramatic effect on the incidence of opportunistic infections and has probably halved the incidence of wasting syndrome in developed countries. Factors contributing to the pathogenesis of HIV-associated wasting are listed in Box 21.2.

The figures for large patient populations are encouraging, and demonstrate convincingly that HAART can prevent wasting. However, it is uncertain whether body weight and BCM recover fully following the introduction of HAART in patients who have established wasting at the time of initiation of therapy. Few clinical trials of HAART collected even simple body-weight measurements, let alone body-composition data. Clinical experience suggests that some patients with severe wasting do regain weight, but carefully conducted prospective studies are needed to quantify this.

One further important point is that the majority of people infected with HIV live in the developing world and, in spite of enormous international efforts to expand access to treatment, in many places less than 50% of those who need treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy actually receive it. HIV-related wasting is therefore likely to remain a significant problem in the populations of developing countries. In some African countries, wasting is such a universal feature of HIV disease that the name ‘slim disease’ has become synonymous with AIDS.

Definition of HIV-associated wasting

The prevalence of wasting syndrome, as defined above, gives only an approximate indication of the true problem of malnutrition in HIV disease. The definition itself is unsatisfactory as it technically excludes wasting associated with recognised opportunistic infections (which are the commonest cause). Malnutrition is considerably more complex than the clinical concept of wasting syndrome. In one study of HIV patients in Germany, 27% of patients had weight loss of >10% but did not meet the other criteria (fever or diarrhoea) for a diagnosis of wasting syndrome. The true incidence of malnutrition in any population of HIV-infected patients will depend on the social, cultural, and medical characteristics of the patients in a practice, but it is probably true to say that a majority of patients will at some stage experience problems with nutrition.

- 10% unintentional weight loss over a period of 12 months or less.

- 10% unintentional BCM loss over a period of 12 months or less.

- Weight loss with body mass index (BMI) < 18.5 kg/m2 (for men) and impaired physical function.

- Weight loss with BCM < 35% of body weight (for men) and impaired physical function.

Thus, due to the inadequacy of the term ‘HIV wasting syndrome’, which, sensu strictu, probably excludes the majority of cases of malnutrition, the term ‘HIV-associated wasting’ will be used throughout this chapter to refer to the occurrence of weight or lean-tissue loss, irrespective of the presence of other clinical symptoms or disease complications. There is no widely accepted definition of HIV-associated wasting, but possible indicators are listed in Box 21.3.

Clinical importance of HIV-associated wasting

There is good evidence that wasting affects survival in HIV-infected patients. One early retrospective study demonstrated that there is progressive depletion of body weight and BCM up to the time of death in AIDS patients, to a body weight of 66% and a BCM of 54% of ideal values. These are very close to values prior to death seen in malnourished people in the siege of Leningrad in 1941–1942, and it is therefore likely that in some patients with HIV the timing of death relates to the magnitude of weight and BCM depletion rather than the specific disease process that causes the wasting. Furthermore, some patients die from malnutrition alone, without other active complications of HIV infection being apparent.

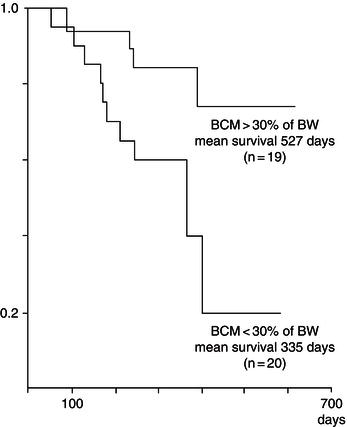

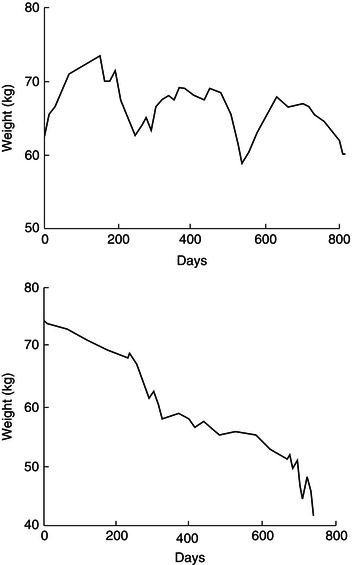

Figure 21.1 Graph of relationship between body cell mass (BCM) and survival. BW, body weight. Adapted from Süttmann et al. (1995) © Wolters Kluwer Health.

Other prospective studies have confirmed the relationship between weight loss and survival, and have suggested that even 5% weight loss can have an independent adverse impact on the disease progression. Depletion of BCM appears to have a more direct effect than body weight. A prospective study of BCM measured by bioelectrical impedance in a German cohort has shown that patients with BCM >30% of body weight had significantly longer survival than those with BCM <30% of body weight at baseline (Figure 21.1).

Apart from the effects on survival, loss of lean tissue has been shown to significantly affect physical function in patients with HIV infection. Involuntary weight loss can also cause profound psychological stress and is often mentioned as one of the most disturbing features of the illness. Patients who have chosen not to disclose their illness to family and friends find it increasingly difficult to maintain the deception, and this may result in social isolation.

The interaction between malnutrition and immune function is well recognised, and wasting may increase morbidity by prolonging recovery from opportunistic infections, thereby lengthening hospital stay and further impairing resistance to nonfatal infections such as oral candidiasis. The consequences of HIV-associated wasting are summarised in Box 21.4.

- decreased survival;

- decreased physical function;

- decreased quality of life;

- decreased immune function.

Patterns of weight change in HIV infection

Weight loss tends to occur in association with disease complications, especially intercurrent infection. A prospective study of weight change in a group of AIDS patients followed for periods of 9–49 months with regular body-weight measurement revealed two distinct patterns of weight loss. Episodes of acute rapid weight loss (median 9.1 kg in 1.7 months) were commonly associated with non-gastrointestinal opportunistic infections such as PCP, bacterial chest infections, and septicaemia. Episodes of chronic unremitting progressive weight loss (median 13.2 kg in 9.5 months) occurred, usually in conjunction with diarrhoeal disease such as cryptosporidium infection. Periods of weight stability or weight gain (usually associated with recovery from opportunistic infections) were also observed (see Figure 21.2).

Patterns of body-composition change in HIV infection

An influential early cross-sectional study in which BCM was measured using total body potassium demonstrated that BCM was lower in patients with AIDS than in controls. There was a relative increase in extracellular water volume, and body fat mass was also decreased, although to a lesser extent than the BCM loss. This pattern of BCM loss with preservation of fat is indicative of a metabolic basis for the wasting process.

Longitudinal studies using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) revealed subsequently that when HIV patients develop wasting they do indeed lose fat, approximately in the proportions that would be expected if calorie restriction were the sole aetiology. There also appears to be a sex difference, with HIV-infected women tending to lose a greater proportion of fat than men when they develop wasting. These differences may reflect differences in the baseline fat mass that influence the pattern of weight loss, or perhaps endocrine differences that influence the wasting process. Some of the variability between patients in body-composition change may also relate to the specific opportunistic infections from which the patients suffer. One study comparing different opportunistic infections found that patients with protozoal diarrhoea had decreased body fat, whereas those with systemic Mycobacterium avium intracellulare infection had decreased skeletal muscle mass. The effects on body composition in HIV-associated wasting are listed in Box 21.5.

Figure 21.2 Patterns of weight change in HIV infection. Adapted from Am J Clin Nutr 1993; 58(3): 417–424. Copyright © American Society for Nutrition.

- body weight ↓

- fat mass ↓

- fat-free mass ↓

- BCM ↓↓

- extracellular water ↑

Energy metabolism in HIV infection

A number of studies have measured one or more component of energy balance in patients with HIV infection. These have shown somewhat conflicting results, but make sense if they are interpreted in conjunction with the clinical characteristics of the patient cohort studied.

In asymptomatic HIV infection, energy intake appears to be normal or slightly increased (by about 15%), possibly as a voluntary or involuntary attempt to compensate for occult malabsorption. This is consistent with the observation of weight stability in early disease. In later stages of HIV disease, energy intake is much more variable, depending on the presence or absence of disease complications at the time the measurement is made. Patients undergoing rapid weight loss (usually in association with an intercurrent infection) have markedly decreased energy intake, and those undergoing weight gain (usually following recovery from opportunistic infections) have normal or increased energy intake. Factors causing a reduced food intake are listed in Box 21.6.

Numerous investigators have shown that resting energy expenditure (REE) is elevated in patients with HIV infection. In those free from acute opportunistic infections, mean REE is elevated by an average of 8–12% irrespective of whether the patient has asymptomatic disease, or has experienced prior weight loss and opportunistic infections. Individual patients show greater variability, with some showing reduced REE suggestive of a starvation response. Others measured at the time of secondary infection have been shown to have a mean REE of around 30% above that of controls in some studies. The differing findings may reflect the heterogeneity of advanced HIV disease. One study found that patients with protozoal diarrhoeal disease had reduced REE, whereas patients with acute PCP and Mycobacterium avium infection had raised REE. The differences in REE between infections may also reflect alterations in the amount of BCM, as well as altered cellular metabolism.

- nausea and vomiting;

- taste disturbances;

- dysphagia;

- early satiety;

- anorexia;

- depression;

- dementia;

- food access or preparation problems;

- voluntary (to avoid diarrhoea);

- voluntary (dietary manipulation to more ‘healthy’ diet).

Due to the difficulty of measurement, few studies of total energy expenditure (TEE) have been conducted in patients with HIV infection. The definitive study using the doubly labelled water method demonstrated an overall reduction in TEE compared with reference control values for normal men. There was a significant positive relationship between TEE and rate of weight change (i.e. patients with rapid weight loss had the lowest TEE). In the same study, physical-activity level (the ratio of TEE/REE) was significantly reduced in patients with rapid weight loss compared with patients with slow weight loss and stable weight (values of 1.3, 1.6, and 1.9, respectively). Thus, increase in TEE cannot be responsible for HIV-associated wasting.

Protein metabolism in HIV infection

Again there is some variability in the findings of studies of whole-body protein metabolism in HIV infection. For example, a study using the 15 N glycine technique demonstrated that asymptomatic patients with AIDS had reduced protein turnover indicative of a starvation-type response. A study using the 13 C leucine technique to measure whole-body protein metabolism in both the fasted and the fed state (using parenteral nutrition) demonstrated that patients with symptomatic AIDS had significantly increased protein turnover compared with controls, with both synthesis and degradation being increased. There was a normal anabolic response to feeding in the HIV-infected patients. The variability of results may reflect the heterogeneity of clinical conditions of the patients that were studied.

Fat and carbohydrate metabolism in HIV infection

Various disturbances of fat metabolism have been described in HIV infection. Fasting triglyceride levels increase with progression of disease, lipoprotein lipase activity is decreased, and the clearance of triglycerides is reduced. De novo lipogenesis, the synthesis of fatty acids from other substrates in the liver, is increased. It is unlikely that these changes in triglyceride metabolism have a significant causal role in the wasting process. They are probably an epiphenomenon reflecting increased activity of cytokines in patients with HIV infection.

In contrast to the insulin resistance that usually accompanies infection, it appears that patients with HIV infection (not on HIV treatment) have increased insulin sensitivity and increased rates of insulin clearance. However, insulin resistance is seen frequently in patients receiving antiretroviral drugs.

Endocrine abnormalities and HIV-associated wasting

Hypogonadism has been well documented in HIV infection, occurring in up to 30% of men with AIDS, although this appears to be becoming less common in the era of effective HIV drug therapy. Various aetiologies have been suggested, including primary testicular disease, the effects of drugs, and hypothalamic dysfunction. It has been shown that androgen levels in hypogonadal men with HIV infection are closely correlated with BCM and exercise functional capacity, suggesting that androgen deficiency plays a role in the pathogenesis of HIV wasting.

There is some evidence for disturbance of the growth-hormone axis in HIV infection, although the data are conflicting. One study found that HIV-infected adults had insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels at the lower limits of normal and had a blunted response to exogenously administered growth hormone. Another found that growth-hormone pulse frequency, amplitude, and area under the curve did not differ between HIV-infected patients and controls.

Cytokines and HIV-associated wasting

It is thought that cytokines may mediate some of the metabolic changes induced by infection, including wasting. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), a cytokine produced by macrophages and monocytes that is a mediator of the immune response, may be responsible for some of the systemic effects of chronic infection. Several studies have found raised levels of serum TNFα or TNF receptors in HIV patients, although others have not. Interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interferon-alpha have also been proposed as mediators of wasting. Although these cytokines appear to be linked to disturbances in fat metabolism in vitro and in vivo, the association between serum levels of these factors and the wasting process in vivo remains unproven.

Treatment of HIV-associated wasting

General approach to treatment

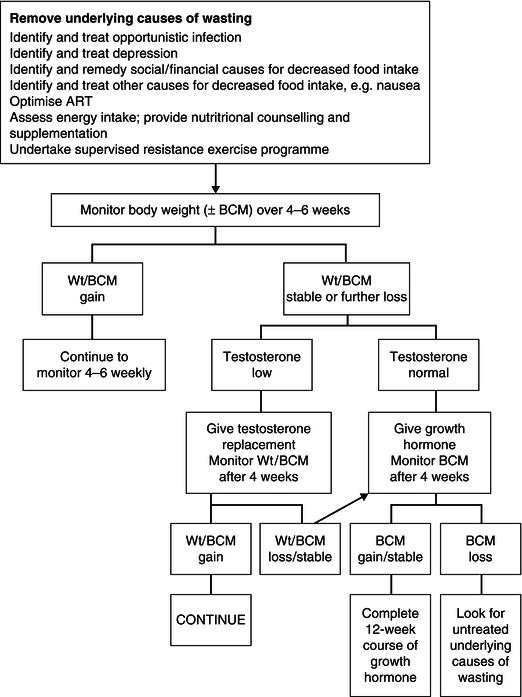

The aim of treatment is to increase lean body mass (BCM in particular) and thereby improve quality of life, physical functioning, and survival. The initial step should be to identify and remove any underlying cause of the wasting. Treatment and recovery from opportunistic infection are often accompanied by repletion of body weight. Initiation of treatment of HIV infection with antiretroviral drugs may also result in some weight gain, although this may be offset by lipodystrophy changes.

Given that the predominant cause of wasting is a decrease in energy intake, the first step in the management process must be to increase calorie intake. However, the disturbances in intermediary metabolism which may be present in HIV disease, particularly at the time of opportunistic infections, may have some impact on the efficacy of nutritional interventions. An intervention which just results in the accumulation of fat and water may be deleterious. Assessment of the composition of any weight gain is a critical part of the evaluation of any therapeutic intervention in HIV wasting. A summary of the treatment of wasting is shown in Figure 21.3.

Nutritional therapy

Nutritional counselling

This is likely to be an important first step, although controlled-trial evidence for its efficacy is lacking. Alternative diets for ‘healthy living’ are popular in the HIV community but may be lacking in important nutrients. Identification of such diets and provision of appropriate advice may result in worthwhile weight gain.

Figure 21.3 Summary of treatment of wasting. ART, antiretroviral therapy; Wt, weight; BCM, body cell mass.

Oral supplements

Many nutritional supplements are available, although few have been subjected to controlled clinical trials comparing them with counselling alone. It appears that these supplements do achieve a worthwhile increase in energy intake (i.e. are not simply substituting for energy intake from normal diet), and this increase in energy intake may result in body-weight gain. However, supplements do not appear to improve immunological recovery (i.e. increase CD4 T-cell count) or improve control of HIV viral replication.

Enteral tube feeding

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree