Marlene L. Durand

Infectious Causes of Uveitis

Uveitis means inflammation of the uvea. The uvea is the pigmented, vascular middle layer of the eye embryologically, sandwiched between the cornea-sclera outer protective layer and the retina. The word uvea comes from the Latin word uva, meaning grape, a translation by Roman anatomists (e.g., Galen) of the Greek term, used because of the grapelike appearance of this highly vascular layer when the white sclera was stripped away. The uvea is composed of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid (see Chapter 113). The iris regulates the amount of light that reaches the retina, the ciliary body produces aqueous humor and supports the lens, and the choroid helps to nourish the retina.

Retinitis is included as a type of uveitis even though the retina is not part of the uvea, because the retina is often involved when there is underlying choroidal inflammation. Uveitis is classified by the ocular structures involved. Several anatomic classification schemes exist, but all divide uveitis into anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis categories (Table 117-1). The site of greatest inflammation determines the category. The International Uveitis Study Group classification is commonly used. In anterior uveitis, inflammation involves the iris (iritis), anterior ciliary body (cyclitis), or both (iridocyclitis). Anterior uveitis is characterized by white blood cells (WBCs) in the aqueous humor. There are often keratic precipitates (cells on the corneal endothelial surface) and iris lesions. Intermediate uveitis refers to inflammation involving the anterior vitreous, ciliary body, and adjacent portion of the retina (called peripheral retina). Posterior uveitis refers to inflammation involving the choroid (choroiditis), retina (retinitis), both (chorioretinitis), or retinal vessels (retinal vasculitis). There may be inflammation of the posterior vitreous. Panuveitis involves all three parts of the uvea. Uveitis may also extend to involve the cornea (keratouveitis) or sclera (sclerouveitis).

TABLE 117-1

Classification of Uveitis and Major Infectious Etiologies in Each Category

| CATEGORY | OCULAR FINDINGS | MAJOR INFECTIOUS ETIOLOGIES (%)* |

| Anterior (iritis, cyclitis, iridocyclitis) | WBCs in aqueous, keratic precipitates, iris nodules, synechiae | Herpes simplex (10%); syphilis (<1%); TB (<1%); Lyme disease (<1%); leprosy (<1%) |

| Intermediate | WBCs or snowballs in the vitreous, pars plana snow bank | Lyme disease (<1%) |

| Posterior (choroiditis, chorioretinitis, retinitis) | Lesions in choroid, retina, or both; vitritis in some | Toxoplasma (25%); CMV (12%)†; ARN (6%); Toxocara (3%); syphilis (2%); Candida (<1%) |

| Panuveitis | WBCs in aqueous and vitreous | Syphilis (6%); TB (2%); Candida (2%) |

* Percentage of uveitis cases in each category (not of total uveitis cases), based on 1237 cases of uveitis seen at Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary, Boston, 1982-1992, by Foster’s group (Rodriguez A, Calonge M, Pedoza-Seres M, et al. Referral patterns of uveitis in a tertiary eye care center. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:593-599).

† Series was before use of highly active antiretroviral therapy, and rate for CMV retinitis would be lower now.

ARN, acute retinal necrosis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; TB, tuberculosis; WBCs, white blood cells.

Other terms commonly used in uveitis appear in Figure 113-1 (see Chapter 113). The eye is divided into anterior and posterior segments by the lens. The iris divides the anterior segment further into anterior and posterior chambers. Aqueous humor fills the anterior segment and is produced and resorbed constantly, with a turnover time of 100 minutes. The posterior segment, a term not to be confused with posterior chamber, is filled with the gel-like vitreous. The vitreous is produced in utero and never regenerated, although it may be surgically removed (vitrectomy) and replaced with clear fluids such as saline.

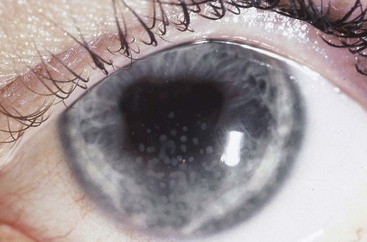

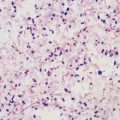

In addition to anatomic location, uveitis is classified as granulomatous or nongranulomatous. Granulomatous does not mean there are granulomas on pathology but describes a type of inflammation in which the WBC cells are condensed into clumps rather than uniformly dispersed. In granulomatous anterior uveitis, granulomatous or mutton fat keratic precipitates form on the endothelial surface of the cornea. These are greasy in appearance and more yellow than nongranulomatous (granular) keratic precipitates (Fig. 117-1). There may also be clusters of WBCs in the iris, called Busacca nodules if in the iris stroma, and Koeppe nodules if at the pupillary margin. In granulomatous uveitis that involves the posterior segment of the eye, there may be WBCs in large clusters (snowballs) in the vitreous, in exudates adjacent to retinal vessels (candle wax drippings), or as granulomas within the choroid (e.g., multifocal choroiditis). Granulomatous uveitis is typical of infections such as tuberculosis (TB), syphilis, and toxoplasmosis, although all may have a nongranulomatous presentation. Two types of autoimmune uveitis, sarcoidosis and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, usually produce a granulomatous uveitis. Nongranulomatous inflammation is more characteristic of autoimmune uveitis, such as Behçet’s disease, reactive arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis.

Epidemiology

In the United States, uveitis has a prevalence of 2.3 million people and causes 10% of all cases of blindness.1 The prevalence in the United States is 70 to 115 cases per 100,000 population, and uveitis affects slightly more women than men.2,3 The prevalence in developing countries is not clear, but a study from West Africa found that uveitis, including that due to onchocerciasis, caused 24% of blindness.4 Uveitis can occur at any age, but the average age at presentation is about 40. Anterior uveitis is the most common type of uveitis, accounting for 90% of uveitis cases in community-based ophthalmology practices and approximately 50% in university referral centers.5–7 Intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis each account for 10% to 15% of uveitis cases in university referral centers but only 1% to 5% in community practices.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Uveitis may be caused by autoimmune conditions, infections, or, rarely, trauma, but 50% of cases are idiopathic. Some cases of intraocular inflammation masquerade as uveitis (masquerade syndromes) but have other causes, such as malignancy (e.g., ocular–central nervous system lymphoma). Infectious uveitis nearly always results from hematogenous spread of infection from another part of the body to the highly vascular uvea. The pathophysiology of uveitis depends on the specific etiology, but in all types there is a breach in the blood-eye barrier. The blood-eye barrier, similar to the blood-brain barrier, normally prevents cells and large proteins from entering the eye. Inflammation causes this barrier to break down, and WBCs enter the eye. Neutrophils predominate in acute uveitis cases, and mononuclear cells predominate in chronic cases.

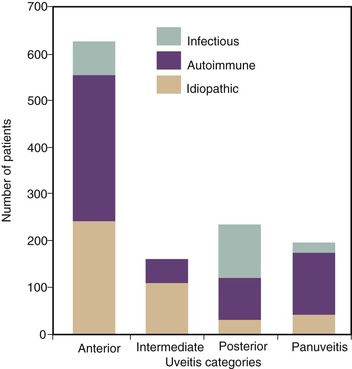

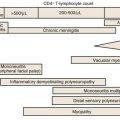

Infections cause about 20% of all uveitis cases, with the most common infectious etiologies being herpetic infections and toxoplasmosis.6 The likelihood of an infectious etiology, however, is greater in some categories of uveitis, such as posterior uveitis, than others. This is illustrated in Figure 117-2, and the frequency of infections is listed by category in Table 117-1. Understanding the types of infectious etiologies by category is helpful in considering possible etiologies for a patient with uveitis. In anterior uveitis, most cases are idiopathic (40%) or associated with a rheumatologic condition (45%), such as seronegative arthropathies, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27–associated disease, reactive arthritis, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. The most common infectious cause is herpetic anterior uveitis, which accounts for almost 10% of cases, whereas syphilis, TB, and Lyme disease each cause less than 1%. Intermediate uveitis most often has an unknown etiology (69%) or is due to sarcoidosis (22%) or multiple sclerosis (8%); infections are extremely rare.5 Posterior uveitis has an infectious etiology in more than 40% of cases. Toxoplasmosis causes 25% to 40% of cases, whereas less common infectious etiologies include cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis, acute retinal necrosis (ARN), Toxocara, syphilis, and Candida.5,8 Major noninfectious diagnoses in a U.S. study were lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and birdshot retinochoroidopathy, an eye disease of unknown etiology (8% each).5 In panuveitis, infections cause 10% of cases and include syphilis, TB, and Candida.5 The remaining 90% of cases are caused by inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis, Behçet’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis, and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, or are idiopathic.

General Clinical Manifestations

Because infectious uveitis usually represents a chronic process, patients often present with no systemic complaints. Patients with anterior uveitis typically present with eye pain and decreased vision. The eye is often injected, especially near the limbus (ciliary flush), and slit-lamp examination shows cells in the anterior chamber. There may be keratic precipitates, iris nodules, or synechiae (adhesions) between the iris and either the cornea or the lens. The vitreous has few, if any, cells and the retina is normal. Patients with intermediate uveitis present with floaters or blurred vision but typically no pain or photophobia. The aqueous is quiet, but vitreous cells are characteristic and are often clumped into so-called snowballs. There may be a white exudate or snow bank over the pars plana. In posterior uveitis, patients often have painless loss of vision as their primary symptom. There are usually few cells in the anterior chamber, but the funduscopic examination shows lesions in the retina or choroid, or both. There may be retinal vasculitis or periphlebitis (venous sheathing). There may be many cells in the vitreous, typical of toxoplasmosis, or no vitritis, typical of CMV retinitis. Panuveitis is characterized by a combination of the previously mentioned findings.

Clinical Manifestations of Major Infectious Etiologies

The most common infectious etiologies of uveitis include herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), syphilis, TB, Toxoplasma, and Toxocara. In the United States, other etiologies include Lyme disease–related uveitis and chronic endophthalmitis due to Propionibacterium acnes or Candida that mimics uveitis.

Anterior Uveitis Due to Herpes Simplex Virus, Varicella-Zoster Virus, and Cytomegalovirus

Of the 10% of anterior uveitis cases that are due to infection, most are caused by HSV, and nearly all of these are due to HSV type 1. This represents reactivation of latent HSV infection, rather than new HSV infection, in nearly all cases. The patient is otherwise well at the time of anterior uveitis, without systemic illness, active cold sores, or other evidence of reactivation HSV infection aside from the eye. Most patients with HSV-related anterior uveitis have either a history of HSV keratitis or active corneal infection at the time of uveitis. HSV keratitis is common, and approximately 40% of patients with ocular herpetic disease have recurrent episodes of anterior uveitis.9 Iritis in an eye with previous herpetic keratitis should be considered herpetic until proven otherwise.10 Herpetic anterior uveitis is nearly always unilateral. Patients complain of eye pain, redness, and photophobia. The cornea may appear cloudy, and slit-lamp examination may reveal interstitial keratitis typical of active recurrent HSV keratitis, or corneal scars from prior episodes. Anterior chamber inflammation may be mild to severe, and there may be a hypopyon or keratic precipitates, or both; keratic precipitates may be small, large, or stellate. Anterior uveitis due to HSV may occur in a patient with no history or findings suggesting herpetic keratitis, but this is thought to be uncommon.11 In the absence of clinical evidence or history of HSV keratitis, there are some clues that suggest herpetic anterior uveitis. These include unilateral disease, decreased corneal sensation, posterior synechiae, acute increase in intraocular pressure (from inflammation of the trabecular meshwork), and iris atrophy (either patchy, sectoral, or diffuse).12 VZV reactivation may also cause a similar anterior uveitis. Sectoral iris atrophy is particularly suggestive of HSV or VZV as the etiology.13 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies of the aqueous in patients with no history of keratitis but recurrent episodes of anterior uveitis with sectoral iris atrophy found HSV in 83% and VZV in 13% of patients.14

Recently, CMV has been implicated in some cases of chronic or recurrent anterior uveitis.15 Similar to HSV and VZV, these cases have been unilateral and chronic, and some have had sectoral iris atrophy. The patients are immunocompetent and have no CMV retinitis or other signs of CMV disease. As for HSV and VZV, serology shows evidence of past rather than acute infection. CMV cases typically have diffuse keratic precipitates and marked intraocular pressure elevation at the time of the uveitis flares.15 Diagnosis has been by PCR of the aqueous. In some cases, there is response to oral valganciclovir hydrochloride. However, optimal duration of treatment is not known. In some cases, recurrence of anterior uveitis has occurred while on therapy, as well as soon after stopping the medication.15,16 It is unclear whether local CMV reactivation is the primary cause of the uveitis or whether it reflects a secondary reactivation in response to another cause of the inflammation.16

Acute Retinal Necrosis

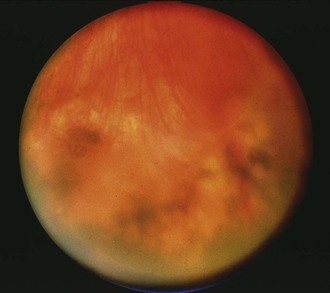

ARN first was described in 1971 and is a rapidly progressive necrotizing retinitis due to herpesviruses that mainly affects immunocompetent patients.17 The American Uveitis Society has established the following four features as diagnostic criteria for ARN: (1) focal well-demarcated areas of retinal necrosis located in the peripheral retina; (2) rapid circumferential progression of necrosis; (3) occlusive vasculopathy; and (4) prominent inflammation (white blood cells) in the vitreous and aqueous.18 HSV types 1 and 2 and VZV cause nearly all cases. A study of 18 ARN patients (negative for human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]) who underwent vitreous biopsy found PCR evidence of VZV in 12 and HSV in 4; 2 were negative by PCR.19 CMV is a rare cause of ARN but must be considered in immunocompromised patients. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been found by vitreous PCR in some cases of ARN, but only in cases in which vitreous PCR was also positive for VZV.19 Some patients with ARN due to HSV have a history of congenital herpes or herpes encephalitis months to years earlier, but these cases are uncommon.20,21 ARN typically begins with a unilateral anterior uveitis. Patients may have mild eye pain or photophobia, then decreased vision in the affected eye. Funduscopic examination with an indirect ophthalmoscope shows one or more foci of retinal necrosis in the peripheral retina, an area not usually seen with a direct ophthalmoscope (Fig. 117-3). The areas of retinitis have sharply demarcated borders and typically spread circumferentially and posteriorly. Vascular sheathing develops along with a dense vitritis. Necrosis of areas of the retina leads to retinal detachment in many patients. Retinal detachment occurs weeks to months after onset of ARN. One study found that more than 50% of patients developed a retinal detachment, and this occurred 3 weeks to 5 months after onset of ARN.19 Treatment with laser to encircle areas of retinal necrosis may help prevent retinal detachment. Treatment with intravenous acyclovir halts progression of the retinitis in ARN in most cases. ARN may involve the other eye several months after the first even in spite of therapy. In an early study, ARN developed in the other eye in 70% of patients who had not received antiviral treatment and in 13% of treated patients.22 In cases that progress despite intravenous acyclovir, intravitreal foscarnet and other systemic antiviral agents may be essential to halt the rapid progression of this blinding infection (see “Therapy”).

Progressive Outer Retinal Necrosis

Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) is a rapidly progressive viral retinitis, most often due to VZV, that involves the deepest layers (“outer” layers) of the retina and occurs primarily in HIV-positive patients with CD4+ T-cell counts less than 100/mm3. It is rare in the United States and other countries in which highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) is widely available for HIV-positive patients. Patients with HIV and PORN typically have CD4+ counts less than 100/mm3, (average 20), but rare cases have been described in HIV-positive patients with CD4+ T-cell higher than 100/mm3.23 A few cases of PORN have been described in other immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients.24 Nearly all cases of PORN are due to VZV, although CMV and HSV have been described. Patients present with vision loss that may be unilateral or bilateral, and examination shows multiple peripheral lesions in the deep (outer) layers of the retina initially. These lesions rapidly coalesce to involve the full thickness of the retina. PORN resembles ARN but is distinguished from it clinically by the following three features: (1) involvement of the outer retina; (2) the absence of any significant inflammation in the vitreous or aqueous humor; and (3) the absence of involvement of the retinal vasculature. Optic neuropathy may precede PORN in rare cases.25 The retinitis in PORN usually progresses rapidly despite systemic antiviral therapy, often resulting in blindness within days of presentation. A few recent successes have been achieved by a combination of systemic and intravitreal therapy (see “Therapy”).

Cytomegalovirus Retinitis

CMV may cause ARN in an immunocompromised host but more typically causes a characteristic CMV retinitis. CMV retinitis affected more than 30% of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the pre-ART era, but now it is rare in countries where ART is widely available. CMV was still the most common cause of ocular lesions in HIV-positive patients seen at a tertiary eye center in India from 1993 to 2010, however.26 CMV retinitis is seen primarily in HIV-positive patients who are ART-naïve or who have failed ART; most have CD4+ T-cell counts fewer than 50/mm3 (average 15 in one recent study).27 CMV retinitis may also occur in other severely immunocompromised patients, such as organ transplant recipients. Patients with CMV retinitis usually present with painless loss of vision. Eye findings typically include white retinal infiltrates; retinal vasculitis, which may have a frosted branch angiitis pattern; and multiple retinal hemorrhages. An important clinical feature is the absence of significant vitreous inflammation. As a consequence, the view of the retina is usually clear. This is in contrast to ocular toxoplasmosis, in which vitritis is common. Patients with HIV who developed CMV retinitis while on ART (ART-failure patients) had less severe disease, but more often bilateral eye involvement, than those who were ART-naïve in one recent study.26 CMV retinitis is discussed further in Chapters 131 and 140.

Ocular Syphilis

The incidence of ocular syphilis appears to be increasing, coincident with the rising incidence of syphilis.28,29 Ocular syphilis may be the presenting feature of syphilis, especially in older adults.30 Syphilis may involve the cornea as an interstitial keratitis or the sclera as a nodular scleritis.31 Uveitis, however, is the most common manifestation of ocular syphilis and is often granulomatous. Syphilis may produce anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, or panuveitis. Syphilitic anterior uveitis is granulomatous in two thirds of patients32 and bilateral in half. Interstitial keratitis, iris nodules, dilated iris vessels, and iris atrophy may be seen. The most common form of posterior uveitis is multifocal chorioretinitis, but other manifestations include focal chorioretinitis, pseudoretinitis pigmentosa, retinal necrosis, neuroretinitis, and optic neuritis. A pale optic nerve head from prior syphilitic optic neuritis may mimic glaucomatous optic atrophy. Chorioretinitis was the type of uveitis seen in 15 of 20 patients with syphilitic posterior uveitis in one review.33 A specific type of focal chorioretinitis, acute posterior placoid chorioretinitis, has been described in syphilis for more than 20 years and is characterized by large, often solitary yellow lesions that are typically in the macula.34 Retinal vasculitis may occur in ocular syphilis, and branch retinal vein occlusions have been described.35

Uveitis may occur in either congenital or acquired syphilis. Typical findings in congenital disease include interstitial keratitis and so-called salt-and-pepper fundi. Interstitial keratitis does not usually occur until the patient is a teenager or young adult. It may be accompanied by an anterior uveitis. The patient may have no other stigmata of congenital syphilis. Glaucoma may result from the inflammation. In acquired syphilis, onset of uveitis may occur in secondary or tertiary syphilis. The most common ocular finding in secondary syphilis is iritis, which accounts for more than 70% of eye findings.35 Symptoms are often acute in onset. In contrast, when ocular syphilis develops in tertiary disease, patients often have slowly progressive decrease in vision as their only symptom. The eye findings are protean and include all of the previously listed findings. In contrast to patients with secondary disease, patients with tertiary disease are often middle-aged or older. They often have no knowledge of prior exposure to syphilis, which likely occurred decades earlier. The diagnosis may be missed if only rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) is checked because these tests are often negative in tertiary syphilis. In a series of 50 patients with a reactive absorbed fluorescent treponemal antibody (FTA-ABS) and eye findings consistent with active or inactive ocular syphilis (e.g., chorioretinitis, optic atrophy, iritis, interstitial keratitis), the average age was 59 and the VDRL was reactive in only 24%.36

All patients with presumed ocular syphilis should have a lumbar puncture to exclude concomitant neurosyphilis, which may be present in 40% of patients.36 Note that a normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) does not exclude ocular syphilis because ocular syphilis is frequently present without evidence of neurosyphilis. Patients who test positive for HIV have a higher rate of concurrent ocular syphilis and neurosyphilis.35,37 All patients with ocular syphilis should be tested for HIV. In a study of 24 patients treated for ocular syphilis between 1998 and 2006, 11 patients were found to be HIV positive, and this was a new diagnosis in 7.38 HIV-positive patients are more likely than HIV-negative patients to have acute, bilateral uveitis with more extensive eye involvement (vitreous, retina, and optic nerve involvement simultaneously).35,39

It is likely that nearly all cases of uveitis and positive specific syphilis serologies represent infection with Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum. It is possible, however, that some patients from areas endemic for yaws or bejel have positive serologies due to exposure to these nonvenereal T. pallidum spp. in childhood but have uveitis from another etiology. Commercial laboratories often employ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits that use one or more cloned antigens or a lysate of the Nichols strain of T. pallidum. These kits vary in specificity and sensitivity, with false positives being common in low-risk populations. Additionally, some authors maintain that uveitis may be a late manifestation of yaws or bejel.40–42 The eye findings they describe are similar to those seen in ocular syphilis, and the diseases cannot be distinguished from syphilis serologically. The possible distinction would be important to the patient because of social implications, although it would not change therapy.

False-positive test results (e.g., low titer RPR, rarely FTA-ABS) may also occur in patients with uveitis, especially as many have underlying rheumatologic conditions that increase the risk of a false-positive test. These are discussed later (see “Diagnosis”).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree