Abstract

Over the past several decades, the widespread adoption of mammographic screening has had a significant impact on the incidence, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of all breast diseases. These changes have been particularly profound for in situ carcinoma of the breast. As a result, there has been a vast increase in the number of publications in the literature with regard to the definition, diagnostic criteria, and both short-term and long-term risks associated with specific histologic variants or types of in situ carcinoma of the breast. It is estimated that by 2020, approximately 1 million women will be living with DCIS—more than double the number in 2005. In situ carcinomas of the breast were first recognized in the early 20th century and were identified morphologically as cells cytologically similar to those of invasive carcinomas but confined to ductal structures within the breast parenchyma. Such lesions were generally found to be located adjacent to areas of invasive carcinoma. The original definitions given to in situ carcinomas of the breast were arbitrary. Opportunities to study the natural history and behavior of such in situ lesions independent of an invasive component of disease or after a surgical procedure less than that of mastectomy were previously rarely encountered. Since that time, several studies relying on the review of archival slide material have demonstrated basic differences between distinct histologic patterns of in situ carcinomas. This subsequently resulted in the distinction between those lesions representing purely markers of increased risk (e.g., lobular carcinoma in situ [LCIS] and atypical hyperplasia, with increased breast cancer risk that was essentially equally distributed to either breast) and committed premalignant lesions (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS], with increased breast cancer risk that was more often reported to be confined to the ipsilateral breast).

Keywords

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ, LCIS, lobular carcinoma in situ, recurrence score

Over the past several decades, the widespread adoption of mammographic screening has had a significant impact on the incidence, diagnosis, classification, and treatment of all breast diseases. These changes have been particularly profound for in situ carcinoma of the breast. As a result, there has been a vast increase in the number of publications in the literature with regard to the definition, diagnostic criteria, and both short-term and long-term risks associated with specific histologic variants or types of in situ carcinoma of the breast. It is estimated that by 2020, approximately 1 million women will be living with DCIS—more than double the number in 2005. In situ carcinomas of the breast were first recognized in the early 20th century and were identified morphologically as cells cytologically similar to those of invasive carcinomas but confined to ductal structures within the breast parenchyma. Such lesions were generally found to be located adjacent to areas of invasive carcinoma. The original definitions given to in situ carcinomas of the breast were arbitrary. Opportunities to study the natural history and behavior of such in situ lesions independent of an invasive component of disease or after a surgical procedure less than that of mastectomy were previously rarely encountered. Since that time, several studies relying on the review of archival slide material have demonstrated basic differences between distinct histologic patterns of in situ carcinomas. This subsequently resulted in the distinction between those lesions representing purely markers of increased risk (e.g., lobular carcinoma in situ [LCIS] and atypical hyperplasia, with increased breast cancer risk that was essentially equally distributed to either breast) and committed premalignant lesions (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS], with increased breast cancer risk that was more often reported to be confined to the ipsilateral breast ).

The classical studies of Wellings and Jensen focused attention on the terminal ductal-lobular unit as a common anatomic site for the development of hyperplastic changes of both the ductal and the lobular type as well as corresponding neoplastic lesions. The terms DCIS and LCIS were once meant to signify separate anatomic origins, with one originating within the ductal structures and the other originating within the lobular structures. However, this anachronous concept is now recognized to be inaccurate. Unfortunately, the idea of distinct lobular and ductal origins for breast neoplasms continues to persist despite our current understanding of neoplastic development within the breast. Currently, the term DCIS refers to patterns of abnormal epithelial cell proliferation associated with a prominent involvement of true ducts within the in situ carcinoma category and has a high risk of local recurrence without adequate local treatment. Thus DCIS is essentially a diagnosis of exclusion, including in its broad sweep any lesion deemed in situ carcinoma that does not exhibit the cytologic features of lobular neoplasia cells. In part, this distinction remains important because the distribution of DCIS and LCIS within a breast as well as between the breasts represents a recognized difference between these two in situ carcinoma entities. In that regard, those studies that have specifically addressed the incidence rate or relative risk of developing a subsequent ipsilateral and contralateral invasive breast cancer in women with in situ carcinoma have traditionally shown a higher incidence rate or relative risk of contralateral invasive breast cancer for those women with LCIS compared with those women with DCIS. Although these differences between DCIS and LCIS have persisted within the literature, the most recently reported series demonstrate that this difference is likely much smaller than previously thought.

Recent Insights Into the Unique Biology of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ and Lobular Carcinoma in Situ

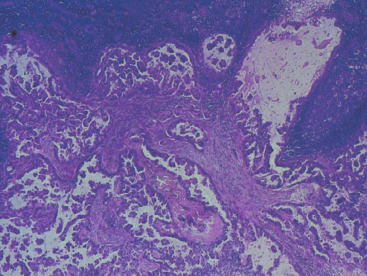

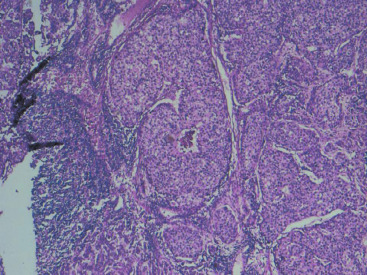

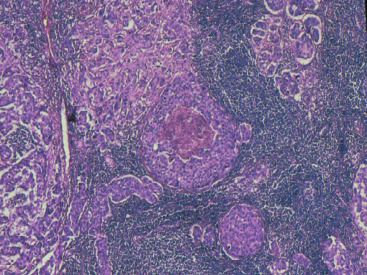

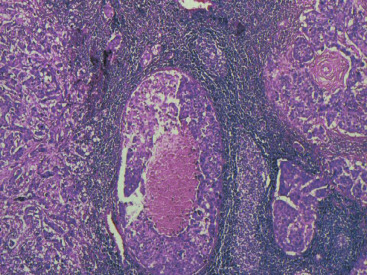

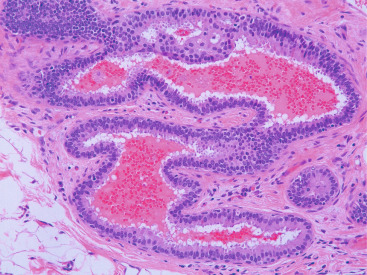

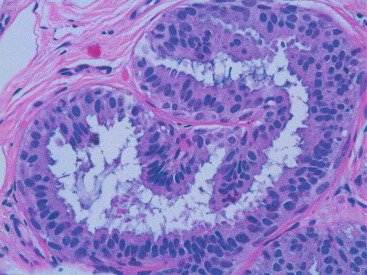

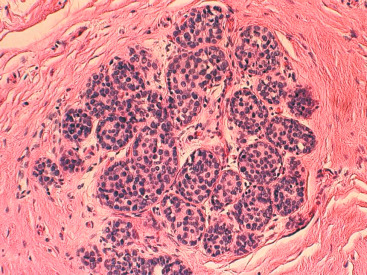

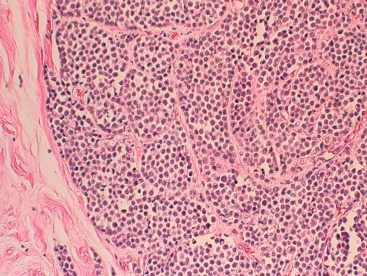

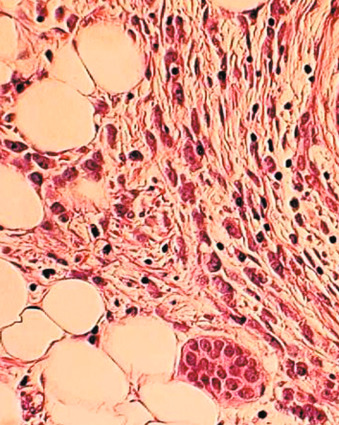

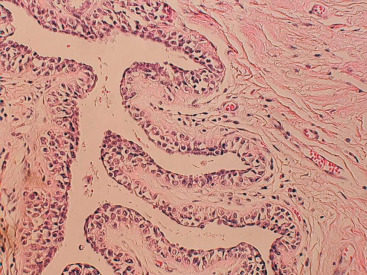

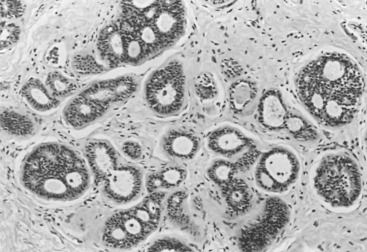

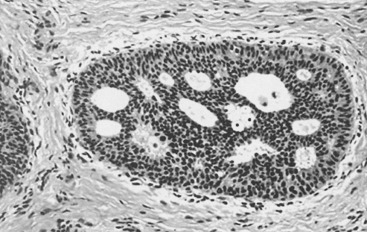

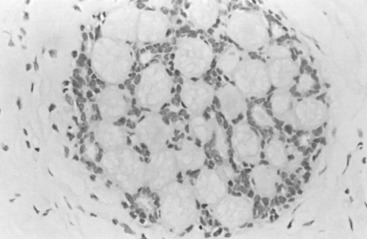

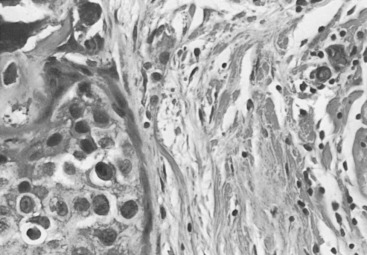

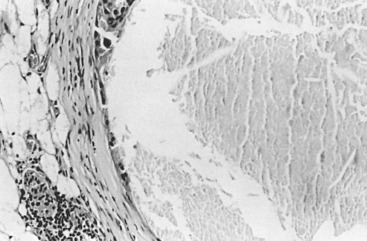

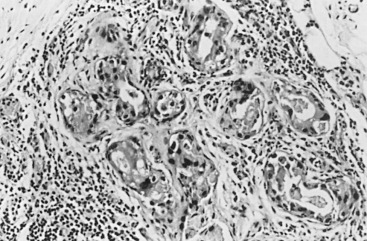

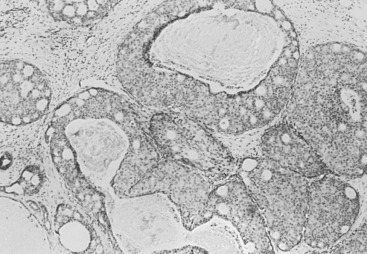

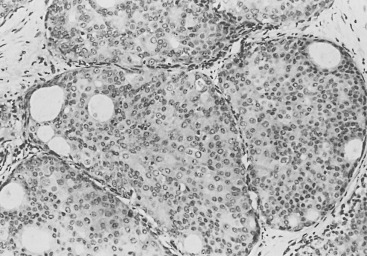

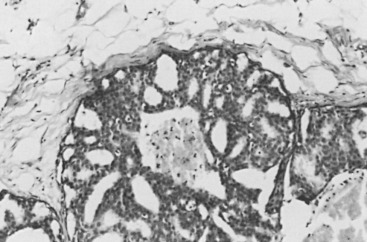

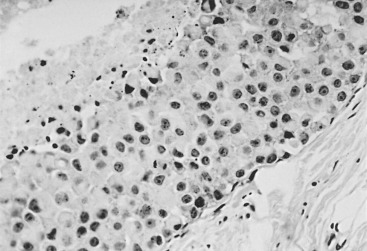

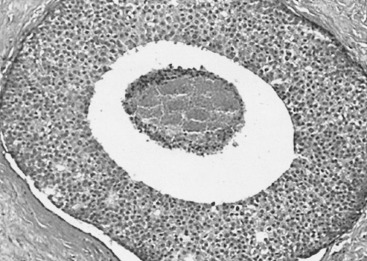

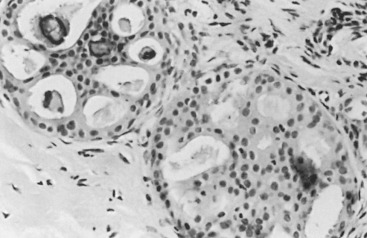

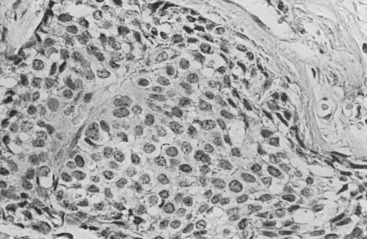

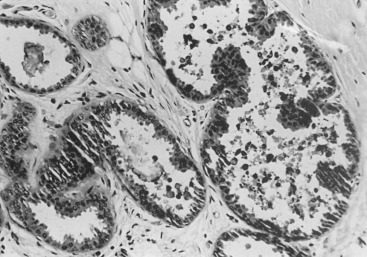

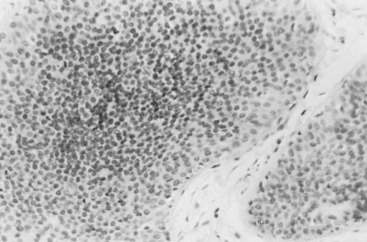

In many respects, DCIS should be regarded as carcinoma of the ductal system, for it possesses all of the molecular and biological abnormalities as frankly invasive carcinoma. DCIS is clonal and frequently expresses abnormal p53 and HER2/neu. It has the same loss of heterozygosity patterns as its invasive counterpart. Using comparative genomic hybridization studies, DCIS exhibits no gains or losses of chromosomal regions compared with its invasive counterpart. Rather, DCIS is held in check by a surrounding layer of myoepithelial cells that exert paracrine suppressive effects on invasion. Because of this, the histopathologic patterns of DCIS usually strongly correlate with its invasive counterpart, when present in individual cases. For example, papillary DCIS ( Fig. 9.1 ) tends to invade as papillary adenocarcinoma. Cribriform DCIS ( Fig. 9.2 ) and solid DCIS ( Fig. 9.3 ) of intermediate nuclear grades tend to invade as a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. Comedo DCIS of high nuclear grade ( Fig. 9.4 ) tends to invade as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. The precursor lesion of DCIS is thought to be atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) for the DCIS of low or intermediate nuclear grades. Simple ductal hyperplasia, based on loss of heterozygosity and genomic hybridization studies, is no longer thought to be a precursor lesion of either ADH or DCIS. A recently described lesion, flat epithelial atypia or columnar cell atypia ( Figs. 9.5 and 9.6 ), based on its abnormal nuclear features and its presence juxtaposed to DCIS, especially high-grade DCIS, is thought to be a possible precursor lesion. However, this has not yet been proved in prospective studies. The evidence is incontrovertible that DCIS can and often does progress to frank invasive adenocarcinoma, and clearly, the same clone is involved.

With LCIS, the story is both similar and different. Emerging evidence has suggested that LCIS is a heterogeneous disease. Some types of LCIS are associated with a 4- to 10-fold increased risk of invasive breast carcinoma ( Fig. 9.7 ). The increased risk can be associated with any type of infiltrating breast carcinoma, including both ductal as well as lobular carcinoma. Other forms of LCIS may be more innocuous. Still others, for example, those that express more nuclear pleomorphism such as pleomorphic LCIS ( Fig. 9.8 ), may actually progress to invasive lobular carcinoma ( Fig. 9.9 ). This latter type of LCIS resembles DCIS in its biology. Still other types of LCIS can mimic other features of DCIS. Some LCIS spreads laterally through the ductal system analogous to Paget disease ( Fig. 9.10 ). This spread of LCIS is aptly termed pagetoid spread . Preliminary molecular studies of LCIS by loss of heterozygosity and genomic hybridization confirm the molecular heterogeneity of LCIS. Some LCIS has few, if any, obvious chromosomal abnormalities. Other types of LCIS exhibit evidence of genomic instability. Still other types of LCIS exhibit the same clonal abnormalities as its invasive lobular counterpart. This molecular heterogeneity suggests that some forms of LCIS may be innocuous, others may confer increased risk for the development of breast cancer, and still others can directly progress to invasive lobular breast cancer. This latter type of LCIS is therefore analogous to DCIS. Clearly, the appropriate therapy would depend on the type of LCIS present. So-called innocuous LCIS could be treated by “watchful waiting,” genomically unstable LCIS with an increased risk of breast cancer could be treated with tamoxifen, and the LCIS that directly progresses to invasive carcinoma could be treated with surgical extirpation. Prospective randomized studies and not just historical controls are needed to resolve the LCIS question.

One consistent molecular difference between LCIS and DCIS is the loss of epithelial cadherin (E-cadherin) expression by mutation, promoter methylation, or cis/trans promoter silencing in LCIS but the maintenance of expression of E-cadherin in DCIS. This observation can be extended to invasive lobular versus invasive ductal carcinoma as well.

Pathology of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

DCIS comprises a heterogeneous group of noninvasive neoplastic proliferations with diverse morphologies and risks of subsequent recurrence and invasive transformation ( Figs. 9.11 to 9.17 ). Although DCIS probably arises predominantly in the terminal ductal-lobular unit, it often extends out to involve extralobular ducts. Compared with LCIS, DCIS is generally more variable histologically and cytologically, with larger and more pleomorphic nuclei and a tendency to form microacini, cribriform spaces, or papillary structures. In some cases, the periphery of these lesions may include patterns overlapping with atypical hyperplasia. Pathologists do not agree on whether small lesions should be considered atypical hyperplasia or in situ carcinoma. In general, lesions that involve only a few membrane-bound spaces and that measure less than 2 to 3 mm in greatest dimension should be regarded as hyperplastic lesions (with or without atypia) and not in situ carcinoma. There is a greater degree of concordance in larger lesions, however. Pathologists tend to agree about the diagnosis of difficult, smaller, borderline lesions if they have agreed on criteria ( Box 9.1 ). Occasionally, it may be difficult to distinguish DCIS and LCIS histologically, with some forms of DCIS characterized by small uniform cells with a solid growth pattern simulating LCIS. In rare instances, in situ neoplastic proliferations are indeterminate. In such cases, they are presumed to have the prognostic implications of both diagnoses (e.g., local evolution to invasion for DCIS and increased general risk in each breast for LCIS). It has been proposed that E-cadherin stains are useful in such overlap cases, but it should be pointed out that no long-term follow-up study has examined the implications of E-cadherin staining or absence thereof for regional breast cancer risk. It has been our approach to diagnose such cases as in situ carcinoma, mixed pattern, and to indicate that a regional risk for local recurrence should be assumed.

a It is evident that the classification scheme should promote consistency.

- 1.

Differentiation, mainly based on nuclear morphology and cell polarization

- 2.

Nuclear grade and necrosis

- 3.

Intersection of nuclear grade and extent of necrosis similar to Silverstein, but with separate identification of special types

Terminology is an important consideration here, and as noted earlier, there are distinct clinical implications concerning the terms lobular and ductal. Although the inherited terms have a historical legacy that may carry other significance, they have the impelling merit of familiarity. It is for us to develop more specific criteria for subtypes and to accept that it is the criteria linked to clinical end point analysis that guides clinical practice. One significant problem is the wonderfully earthy word comedo . It refers to the lowly comedones (e.g., acne) of common experience from our teen years, an unfailing image of the gross appearance of these lesions. Bloodgood coined the term comedo-adenoma because when treated with mastectomy in the halstedian era, it was associated with long-term survival. For Bloodgood, the alternative to carcinoma was adenoma, a lesion capable of cure when adequately excised. The term comedo remains descriptive and is now somewhat confusingly used to indicate both a type of DCIS with a coagulation-type necrosis and frequent nuclear debris, as well as merely the evidence of necrosis alone (comedo necrosis). Today most students of DCIS use comedo as a modifier for DCIS, signifying high-grade lesions that exhibit necrosis.

A major transition in our thinking regarding DCIS was the idea that perhaps not all DCIS cases were the same and that the different histologic appearances of DCIS might in fact have important clinical implications. Translating this concept into practical terms, it was suggested that if comedo-type DCIS did have a more menacing clinical import, then one should err on the side of including any questionable case within this category. Thus in 1989, the critically important concept of further stratification was introduced as a part of the inception of the modern era of understanding of DCIS. Because minor amounts of necrosis may be seen in the common hyperplasias without features of atypia, specific guidelines are necessary to make appropriate stratifications. Thus, inclusion of an intermediate-grade category has been adopted by the majority of DCIS classifications put forth since the early 1990s ( Table 9.1 ) to recognize examples with minimal necrosis and a moderate degree of nuclear pleomorphism.

| Necrosis | NUCLEAR GRADE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||

| Lagios | + | Intermediate | High | |

| — | Low | |||

| Silverstein | — | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| — | Group 1 | Group 3 | ||

| Solin | + | Comedo | ||

| — | Noncomedo | |||

Conventionally, DCIS has been classified on the basis of architectural features, such as comedo, cribriform, papillary, solid, and micropapillary. Although comedo-type DCIS includes advanced nuclear abnormalities within the neoplastic proliferation as part of the definition, the diagnosis of other patterns of DCIS were based on architecture alone. These patterns were accepted to be overlapping when DCIS was considered one entity and not held to have separate clinical or biological implications. The first indication that distinguishing among comedo, noncomedo, and micropapillary subtypes, as well as separation by grade, was of clinical utility certainly inaugurated the modern era of DCIS in 1989.

The increasing use of breast conserving therapy (BCT) in the treatment of mammographically detected DCIS has permitted studies on factors that predict local recurrences and invasive events in the remaining breast after excisional biopsy. Before a large number of small mammographically detected DCIS cases were found with screening, mastectomy was the only acceptable treatment for DCIS and remains a standard treatment for multifocal and multicentric disease.

Three prognostic factors have been shown to be important in local control of DCIS after attempts at BCT : (1) the extent (size) of disease in the breast (and its corollary, the residuum after an attempt at excision), (2) the status of margins (also reflecting residual disease in the breast), and (3) the grade of the DCIS (and possibly pure subtype, particularly micropapillary). The most significant of these factors appears to be margin status, followed by histologic grade. High nuclear grade and necrosis together define forms of DCIS at much higher risk of local recurrence and invasive transformation. The grade of a DCIS is largely independent of the conventional pattern classification. For example, lesions of high nuclear grade can exhibit any architectural pattern (although lack of precise patterns is most common). However, as recognized in the classification system of Holland and associates (see Box 9.1 ), ordered intercellular relationships are most common in lesions of low nuclear grade. There is a growing consensus that classifications based on nuclear grade and necrosis can identify the majority of patients with DCIS who are at risk for short-term local recurrence and invasive transformation after excision with or without irradiation. Most of these short-term recurrences are associated with DCIS exhibiting high (3/3 or grade III) nuclear grade morphology and significant coagulative necrosis. Such lesions would be conventionally classified as comedo DCIS. Studies using conventional classification schemes have shown that most short-term failures are associated with comedo-type DCIS. It should be recalled that the term comedo-type DCIS is not synonymous with high nuclear grade when it is used to indicate necrosis only. Some lesions exhibiting comedo-type necrosis and a solid growth pattern are composed of intermediate-grade and, in rare cases, borderline low-grade nuclei ( Figs. 9.18 to 9.27 ).

Information regarding the potential for recurrence of low-grade (noncomedo-type) DCIS after biopsy or BCT resides in a small number of published studies. It is clear that in the short term (5–10 years), few local recurrences or invasive transformations occur. However, a recent update of the only study of low-grade DCIS present at biopsy (without planned excision ) and with extended follow-up noted a substantially delayed recurrence rate of invasive lesions (e.g., approximately 37% and 50% at 25 years and more than 40 years of follow-up, respectively). Although the sample is small, it is significant that recurrences were generally in the same quadrant and, in some women, in the site of the prior biopsy, thus representing a biology identical to that of higher-grade DCIS and a risk that does not diminish after menopause. This biology of DCIS should be contrasted with that of risk marker lesions (e.g., ADH and atypical lobular hyperplasia [ALH]), which do not predict the side of involvement and in which risk diminishes postmenopausally (at least for ALH and LCIS).

There are several published classifications of DCIS, many of which use nuclear grade and necrosis as the major distinguishing features in a general classification applying to most cases of specific subtypes. The separations achieved by these classifications are different and in part may affect the interpretation of outcome results ( Table 9.2 ). DCIS characterized by nuclear morphology (high grade III; e.g., advanced atypia) and necrosis is uniformly classified as high grade. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) classification, although it does not use conventional nuclear grade or necrosis as major discriminates, would also regard this as a high-grade or, in their terminology, a poorly differentiated DCIS. Fisher and colleagues summarized the pathology analysis from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) studies on DCIS and noted that DCIS with grade III nuclei and DCIS that exhibited larger areas of necrosis (greater than one third of ducts involved) had a higher local recurrence rate. The authors reported these results separately, not analyzing the risk associated with the two features in concert. Despite the differences in classification, it would appear that high-grade DCIS can be recognized uniformly, with all investigators showing that the high-grade subtype, so defined, has the highest risk of local recurrence and invasive transformation.

| Histology | Nuclear Grade | Necrosis | Final DCIS Grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comedo | High | Extensive | High |

| Intermediate b | Intermediate | Focal or absent | Intermediate |

| Noncomedo c | Low | Absent | Low |

b Often a mixture of noncomedo patterns.

The recognition that necrosis and high nuclear grade usually cluster together may foster agreement between observers by using limited necrosis as a way of defining an intermediate-grade category. The separate classifications are less consistent with regard to the remainder of the heterogeneous noncomedo-type group (see Table 9.1 ). DCIS with grade III nuclei but without necrosis, an uncommon situation, is classified as high grade by Silverstein and coworkers but “noncomedo” (a lower grade) by Solin and associates. Lagios and colleagues and Silverstein and coworkers use nuclear grade to separate the remaining DCIS groups. However, Lagios and colleagues classify low-grade DCIS as grade I nuclei without necrosis and intermediate-grade DCIS as grade II with or without necrosis. Silverstein and coworkers separate DCIS with nuclear grades I and II on the basis of necrosis. Group I (low grade) may exhibit grade I or II nuclei but no necrosis, whereas DCIS with grade I or II nuclei but with any necrosis is classified as intermediate (group II). Solin and associates regard all DCIS without grade III nuclei and necrosis as noncomedo-type DCIS. Despite these differences in classification, all investigators have shown a substantially diminished local recurrence rate for DCIS that is not characterized by grade III nuclei and necrosis. Moreover, in those studies in which DCIS is divided into three groups, as opposed to the dichotomous comedo/noncomedo structure, there is a recognizable intermediate group (intermediate grade, group II, intermediately differentiated) that exhibits a morphology and risk intermediate between low- and high-grade DCIS.

Classification of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

Although nuclear grade and necrosis would appear to define most of the risk associated with DCIS, certain architectural patterns appear to bear clinical significance independent of the nuclear grade. For example, DCIS with almost pure micropapillary architectural features is strongly associated with extensive disease, that is, within seemingly separate foci of different quadrants. This growth pattern makes adequate excision extremely difficult. In some cases, mammographic and histopathologic evidence of disease is present in all four quadrants of the breast. As a result, most clinical studies that define DCIS with micropapillary features and low nuclear grade were based on excisions without theoretically adequate margins of resection.

Conventional classification of DCIS covers perhaps 85% of what is recognized as noninvasive ductal carcinoma. A number of less common subtypes remains to be fully defined morphologically and with regard to risk. Proliferations with apocrine features, bridging the spectrum from minimal atypia to frank DCIS, were the subject of a proposed classification by O’Malley and associates. Because of the difficulty of applying traditional rules regarding cellular atypia and architecture to apocrine lesions, this schema proposed that definitive diagnoses of low-grade apocrine DCIS be limited to cases measuring at least 8 mm in size. In addition, a borderline category was proposed for lesions measuring 4 to 8 mm, with the suggestion that these lesions had the relative risk implications of at least ADH. Furthermore, apocrine DCIS, which is characteristically estrogen receptor negative, progesterone receptor negative, and androgen receptor positive and represents a heterogeneous group of lesions ranging from low-grade lesion (which should be differentiated from atypical hyperplastic apocrine lesions) to obvious malignant, high-grade tumors (which are difficult to recognize as apocrine), was more recently classified into three histologic grades based on nuclear grade and necrosis by Leal and colleagues, similar to schema for classical DCIS. Confirmation of the utility of any of these approaches to classifying such apocrine lesions awaits long-term follow-up analysis of cases treated with conservative surgery.

Another contender for special-type status is the so-called endocrine type of DCIS, which presents a particularly low-grade pattern of disease. Similarly, a possible special type characterized by hypersecretory features is discussed subsequently. In all of these less common special types of DCIS, a major limitation is the lack of precise confines of histologic definition that specifically and reproducibly describes the entire spectrum of changes with a linkage to clinical implications corroborated by long-term follow-up studies. With this background of remaining uncertainty, it is generally recommended that all the traditional rules for characterization and classification be applied to these less common entities, so as not to misdiagnose or mistreat such in situ lesions.

The classification of DCIS has been subjected to different approaches, each with advantages and disadvantages. The purpose of any classification scheme for DCIS is to predict the likelihood of recurrences and the likelihood of progression to invasion, and no classification scheme is ideal from these perspectives. For these reasons, newer classification schemes are continually evolving. The classification scheme proposed by Page and Lagios is summarized (see Tables 9.1 and 9.2 ). Several other DCIS classifications are presented (see Box 9.1 ), providing a basis from which to understand the slightly varied approaches. The major differences between Page’s classification and most of the other schemes are that Page’s uses the intersection of two variables—necrosis and nuclear grade—to foster agreement. It is common to debate between adjacent nuclear grades, viz, 1 or 2, and 2 or 3. The extensiveness of the necrosis is to be used to aid in the resolution of these issues. In a test set, agreement was fostered by this approach. The second feature of Page’s scheme is to separate some special types of DCIS because they present patterns not readily allowing grading. In the special case of pure (not intermixed with solid or cribriform) micropapillary DCIS, Page believes that the usual extensiveness of disease is independent of the nuclear grade. It should be noted that separating special types from the majority of cases is precisely what we do with invasive disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree