Rationale

Hyperglycaemia, DKA, and HONK are preventable short-term complications of diabetes. When hyperglycaemia does occur, effective proactive management can reduce the progression to DKA and HONK and limit the attendant metabolic derangements should these conditions occur. People with well controlled diabetes do not usually experience higher rates of intercurrent illness than non-diabetics. However, those with persistent hyperglycaemia may have lower immunity and are at increased risk of infections including infections caused by organisms that are not normally pathogenic, tuberculosis, and have a poorer response to antibiotics (Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group 2005). Infection is the most common cause of DKA and HONK.

Prevention: proactively managing intercurrent illness

Prevention strategies consist of educating the person with diabetes and their family about how to prevent intercurrent illness or proactively managing intercurrent illnesses to limit the metabolic consequences. Illness prevention/management strategies should be individualised and based on a thorough physical, psychological, and social assessment using a risk management approach. Illness prevention education should encompass:

- Proactive health care such as identifying key illness risk times, for example, colds and flu during winter, having a documented plan for managing illness, and a kit containing essential equipment and information such as ketone test strips and relative’s and health professional’s telephone numbers.

- Recognising and managing the signs and symptoms of DKA and HONK, which includes the importance of monitoring blood glucose and ketones and using the information to adjust glucose lowering medicine doses or seek medical advice and how to maintain fluid intake.

- How to adjust insulin/OHAs and dietary intake to control blood glucose levels.

- When to seek assistance.

In addition, health professionals should regularly reassess the individual’s illness self-care capability including:

- Knowledge, according to the factors outlined in the preceding list.

- Physical ability to manage such as mobility, sight, manual dexterity, and other activities of daily living, bearing in mind these may all be compromised by hyperglycaemia. This is an important aspect of long-term complication screening programmes. Groups likely to need assistance are children, pregnant women, frail older people who live alone, those who are acutely ill and those who are depressed. The most effective management strategy for these people may be to seek health professional advice quickly.

- Psychosocial factors such as mental health and coping skills, cognitive function, and available support from family of other carers considering their state of health and coping ability especially in older people.

- Preventative health care strategies such as vaccinations, mammograms, prostate checks, usual metabolic control, and their sick day management plan and kit. Annual influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are recommended for people with diabetes, COPD, cardiovascular disease including children with these conditions (National Asthma Council 2005). Mortality increases by 5–15% in people with diabetes during influenza epidemics especially those with cardiovascular and renal complications (Smith et al. 2004). The increased risk may be due to older age cardiovascular disease or to the diabetes itself due to the impaired immune response due to DKA/HONK (Diepersloot et al. 1990). Kornum (2007) suggested Type 2 diabetes predicted mortality associated with pneumonia and further, hyperglycaemia on admission, >11 mmol/L in diabetics and >6 mmol/L in non-diabetics, predicts pneumonia-related mortality.

- Observational data suggest influenza vaccination prior to and during an influenza epidemic reduces the associated hospital admissions and mortality in people with diabetes (Wang et al. 2004). Thus, all people with diabetes aged 6 months and older should receive annual influenza vaccination unless contraindicated. Contraindications include allergy/anaphylactic reaction to eggs and/or the vaccine, intercurrent illness with fever >38°C.

- Regular medicine reviews including complementary and over-the-counter medicines. In particular, assessing the continued need for diabetogenic medicines such as atypical antipsychotic medications, glucocorticoids and thiazide diuretics. If these medicines are necessary and there are no alternatives, the lowest effective dose should be used.

- Early recognition of new presentations of diabetes.

- Good access to competent medical and nursing care and ongoing education.

- Good knowledge on the part of people with diabetes and health professionals.

- Good communication/therapeutic relationship between the person with diabetes and their health professionals (see Munro et al. 1973: this is an old reference but it is still pertinent in the light of the frequent presentations to hospital with hyperglycaemia-associated conditions).

- Psychological screening should be incorporated into routine complication assessment programmes (Ciechanowski et al. 2000; Dunning 2001).

Self-care during illness

People with Type 1 diabetes are at greatest risk of DKA but DKA can occur in seriously ill Type 2 and HONK is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. A suggested plan for monitoring blood glucose and ketones is shown in Table 7.1 (International Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Diabetes 2000; Kitabchi et al.2001; American Diabetes Association 2004; Laffel et al. 2005; Australian Diabetes Educators Association (ADEA) 2006; Dunning 2007). In the early stages of the illness people may be able to be managed at home if they are capable of self-care, have support and can telephone their doctor at least every 1–2 hours. Admission to hospital is advised in the following situations:

- Children especially younger than 2 years.

- Persistent vomiting and/or bile-stained vomitus.

- Persistent diarrhoea.

- Blood glucose persistently, 4 mmol/L or >15 mmol/L and ketones present

- Severe localised abdominal pain.

- Hyperventilation (Kussmaul’s respirations)

- Dehydration.

- Coexisting serious illness.

- Impaired conscious state.

- The individual, parent or care providers are unable to cope

Hyperglycaemia

Hyperglycaemia refers to an elevated blood glucose level (>10 mmol/L) due to a relative or absolute insulin deficiency. The symptoms of hyperglycaemia usually occur when the blood glucose is persistently above 15 mmol/L. In people with an established diagnosis of diabetes. The cause of the hyperglycaemia should be sought and corrected to avoid the development of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or HONK. Hyperglycaemia, DKA and HONK are often referred to as short-term complications of diabetes. DKA develops relatively quickly. HONK usually evolves over several days to weeks.

Table 7.1 Self-managing blood glucose, ketones and fluid during illness. These recommendations should be tailored to the individual’s self-care capabilities, available assistance, and their physical condition. Ketosis can develop rapidly in people using insulin pumps. The underlying cause needs to be ascertained and treated.

| Type 1 | Type 2 | |

| Blood glucose (BG) | Monitor 2 hourly | Monitor 2 hourly |

| Monitor ketones 2 hourly if >15 mmol on two consecutive occasions in a 2–6 hour period | If >15 mmol on two consecutive occasions in an 8–12 hour period increase monitoring frequency to 2–4 hourly | |

| QID testing may be adequate in people managed with diet and exercise. | ||

| #Blood ketones <1 mmol/L | BG 4–15 mmol/L recheck in 2 hours | Follow the same test procedure as described for Type 1 diabetes. |

| 1–1.4 mmol/L: | BG, <8 mmol/L extra sweet fluids: >8 mmol/L extra 5% insulin | Ketones are less common in Type 2 diabetes but do occur. |

| >1.5 mmol/L: | BG, <8 mmol/L extra sweet fluids: >8 mmol/L extra <1 mmol/L | |

| <1 mmol/L | BG 15–22 mmol/L 5% extra insulin | |

| 1–1.4 mmol/L | 10% extra insulin | |

| >1.5 mmol/L | 15–20% extra insulin and hospitalise if ketones persist | |

| <1 mmol/L | BG >22 mmol/L 10% extra insulin | |

| 1–1.4 mmol/L | 15% extra insulin | |

| >5 mol/L | 20% extra insulin and hospitalise if ketones persist | |

| Medicines | Give supplemental doses of quick/rapid acting insulin 2–4 hourly | OHAs |

| Consider ceasing metformin | ||

| Increase sulphonylurea dose unless on maximal doses or on slow release preparation when insulin is preferreda | ||

| OHA and insulin | ||

| Supplemental doses of quick/rapid acting insulin | ||

| Insulin treated | ||

| Supplemental doses of quick/rapid acting insulin | ||

| Refer to hospita | Unable to maintain fluid intake | Unable to maintain fluid intake |

| Blood glucose and ketones not falling despite supplemental insulin | Blood glucose and ketones not falling despite supplemental insulin | |

| Unable to self-care and no support available | Unable to self-care and no support available | |

| Condition deteriorating | Condition deteriorating | |

| Fluids | BG <4 mmol/L usual meals and extra sweet fluids if tolerated ∼10–12 mmol/L and able to tolerate food 150 mL easily digested fluid every 1–2 hours, for example, soup, fruit juice, ice cream. | BG <4 mmol/L usual meals and extra sweet fluids if tolerated ∼10–12 mmol/L and able to tolerate food 150 mL easily digested fluid every 1–2 hours, for example, soup, fruit juice, ice cream. |

| BG >12 mmol and unable to tolerate food 100–300 mL low calorie fluids every hour, for example, gastrolyte, low calorie soft drink, mineral water, water | BG > 12 mmol and unable to tolerate food 100–300 mL low calorie fluids every hour, for example, gastrolyte, low calorie soft drink, mineral water, water. | |

| Unable to tolerate fluids at any BG level refer to hospital | Unable to tolerate fluids at any BG level refer to hospital |

a If the person has no experience of insulin they will need reassurance and a careful explanation about why insulin is needed. If they are not able to manage or do not have assistance and home nursing is not available they may need to be managed in hospital.

Hyperglycaemia disrupts multiple organ systems and needs to be treated to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with acute illness. Fluid resuscitation corrects dehydration, improves microcirculation, and reduces tissue damage during acute sepsis, which helps correct hyperglycaemia, but increased insulin doses and/or dose frequency or rescue insulin therapy in Type 2 diabetes is usually required.

Many researchers have demonstrated that hyperglycaemia is associated with adverse outcomes in hospitalised people both diabetics and non-diabetics and that controlling the blood glucose improves outcomes (Abourizk et al. 2004; Clement et al. 2004; ACE Taskforce 2004; ACE/ADA Taskforce 2006). There is still debate about whether continuous IV insulin infusion is the safest and most effective therapy despite the well described benefits in both diabetic and non-diabetics (Van den Berghe et al. 2001). Intensive insulin therapy protects renal function in critically ill patients and reduces the incidence of oliguria and the need for renal replacement therapy in surgical patients. Intensive insulin infusion is also associated with improved lipid and endothelial profile (Schetz 2008).

The greatest concern appears to be causing hypoglycaemia (Schulman et al. 2007; Brunkhorst 2008). Likewise, it is not clear whether less stringent blood glucose targets achieve similar morbidity and mortality reductions (Schulman et al. 2007). Laboratory or capillary blood glucose tests are the best method of monitoring blood glucose during illness. Capillary tests are undertaken more frequently except in intensive care situations and may give better insight into the blood glucose pattern (Cook et al. 2007).

Quality management organisations in the US are currently developing hospital outcome measures for managing hyperglycaemia in hospitalised patients (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations 2006). Despite the evidence that insulin requirements increase during illness, insulin doses are often reduced, even in the presence of significant hyperglycaemia, because health professionals are concerned about causing hypoglycaemia, whereas the factors contributing to hypoglycaemia are only rarely investigated and addressed (Cook et al. 2007).

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA)

Diabetic ketoacidosis is a life-threatening complication of diabetes. The basic pathophysiology consists of a reduction in the effective action of circulating insulin and an increase in counter-regulatory hormones. Glucose is unable to enter the cells and accumulates in the blood. Insulin deficiency leads to catecholamine release, lipolysis and the mobilisation of free fatty acids and subsequently ketone bodies, B-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, and acetone, resulting in metabolic acidosis (ADA Position Statement 2002). Protein catabolism also occurs and forms the substrate for gluconeogenesis, further increasing the blood glucose. At the same time, glucose utilisation in tissues is impaired. DKA usually only occurs in Type 1 patients, but may occur in Type 2 people with severe infections or metabolic stress. The mortality rate in expert centres is <5% but is higher at the extremes of age and if coma and/or hypotension are present (Malone et al. 1992; Chiasson et al. 2003).

Diabetic ketoacidosis is characterised by hyperglycaemia, osmotic diuresis, metabolic acidosis, glycosuria, ketonuria and dehydration. The definition by laboratory results is blood glucose >17 mmol/L; ketonaemia (ketone bodies) >3 mmol/L; acidosis, pH <7.30 and bicarbonate <15 mEq/L.

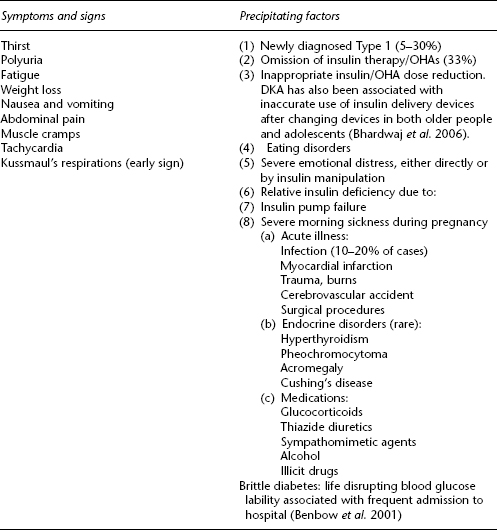

The signs, symptoms, and precipitating factors for DKA are shown in Table 7.2, while Figure 7.1 outlines the physiology and the signs and symptoms that occur as a result of impaired glucose utilisation, and the biochemical manifestations found on blood testing.

Late signs, that is severe DKA

The initial signs and symptoms of DKA (polyuria, polydipsia, lethargy, and Kussmaul’s respirations) are an attempt by the body to compensate for the acidosis. If treatment is delayed the body eventually decompensates. Signs of decompensation (late signs) include:

- Peripheral vasodilation with warm, dry skin.

- Hypothermia.

- Hypoxia and reduced conscious state.

- Reduced urine output (oliguria).

- Reduced respiratory rate – absence of Kussmaul’s respirations.

- Bradycardia.

The signs and symptoms can be masked by intercurrent illness. For example, pneumonia can cause tachyapnoea, dry mouth and dehydration, abdominal pain and vomiting are symptoms of gastrointestinal disease, likewise, abdominal pain is usual in appendicitis and labour. Polyuria and polydipsia can be difficult to detect in toddles not yet toilet trained, bed wetters, and incontinent older people. Unexplained bed wetting in these groups needs to be investigated and DKA considered when the onset is sudden. Hypothermia as a result of peripheral vasodilation can mask fever due to underlying infection.

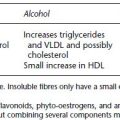

Table 7.2 Early signs, symptoms, and precipitating factors of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Differential diagnosis

- Starvation ketosis, which can be determined by taking a careful clinical history of the presentation.

- Alcoholic ketosis where the blood glucose is usually only mildly elevated or low.

Figure 7.1 An outline of the physiology, signs, and symptoms and biochemical changes occurring in the development of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

The implications of the metabolic and physiological changes associated with DKA are shown in Table 7.3.

Assessment

The following factors should be established:

- Whether the person has known diabetes;

- Usual insulin/OHA dose, dose interval and type/s of insulin/OHA;

- The time the last dose was taken and dose administered;

- Presence of fever, which can be a sign of myocardial infarction as well as infection;

- Duration of the deteriorating control/illness;

- Remedial action taken by the patient;

- Whether the person has taken any other medications, complementary medicines, alcohol or illegal drugs;

- Conscious state.

A thorough physical assessment should be undertaken and blood taken to:

- Establish the severity of the DKA: glucose, urea and electrolytes, pH and blood gases, degree of ketonaemia. If severe acidosis is present, pH <7.1, and the blood glucose is not significantly elevated alcohol, aspirin overdose or lactic acidosis need to be excluded especially in older people. Ketones in the presence of low blood glucose can indicate starvation.

- Assess the cause: full blood count, cardiac enzymes, blood cultures, ECG, chest X-ray, urine culture.

Table 7.3 The metabolic consequences of diabetic ketoacidosis and associated risks. Many of these changes increase the risk of falls in older people.

| Metabolic consequences of ketoacidosis | Associated risk |

| Metabolic acidosis | Nausea and vomiting |

| Cardiac arrest | |

| Hyperlipidaemia | Thrombosis/embolism |

| Haemoconcentration and coagulation changes | Myocardial infarction, stroke, thrombosis |

| Dehydration | Volume depletion |

| Renal hypoperfusion | |

| Can cause acute tubular necrosis | |

| Gastric stasis | Inhalation of vomitus, aspiration pneumonia |

| Hyperkalaemia but overall deficit in total potassium due to loss in osmotic diuresis. | Cardiac arrhythmias |

| Hyperglycaemia, which is exacerbated by glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis | Plasma hyperosmolality |

| Cellular dehydration | |

| Osmotic diuresis | |

| Compromised immune function leading to infection and delayed wound healing, also thrombosis, low mood, visual changes | |

| Glycosuria | Hyponatraemia and ketonaemia, which contributes to sodium, potassium, and chlorine loss |

| Hyponatraemia is common but if sodium is <120 mmol/L may indicate hypertriglyceridaemia | |

| Abdominal pain | Unnecessary surgery, inappropriate pain relief causing further respiratory distress, missed labour |

| Death |

Aims of treatment of DKA

Treatment aims to:

- dehydration

- electrolyte imbalance

- ketoacidosis

- hyperglycaemia by slowly reducing the blood glucose to 7–10 mmol/L). Hyperglycaemia, relative insulin deficiency, or both, predispose people with and without diabetes to complications such as severe infection, polyneuropathy, multiorgan failure and death (Van den Bergh et al. 2001).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree