Rationale

Best practice diabetes education and care relies on a combination of the best available evidence, intuition, and clinical judgement, effective communication skills and the informed participation of the person with diabetes. Careful assessment enables physical, psychological, spiritual and social issues that impact on care to be identified and incorporated into nursing management and discharge/transition plans. Life balance and emotional well being are essential to achieving metabolic targets.

Holistic nursing

Holistic care aims to heal the whole person using art and science to support the individual to mobilise their innate healing potential: that is, to become empowered. Healing occurs when the individual embraces and transforms traumatic life events and is open to and/or recognises his or her potential (Dossey et al. 1995, p. 40). Transcending traumatic life events such as the diagnosis of diabetes or a diabetes complication is part of the spiritual journey to self-awareness, self-empowerment, and wholeness. Significantly, spirituality is not the same as religion, although it may encompass religion (Dossey et al. 1995, p. 6; Parsian & Dunning 2008).

Thus, in order to achieve holistic care, nurses must consider the individual’s beliefs and attitudes because the meaning people attach to their health, diabetes, and treatment, including medicines, affects their self-care behaviour and health outcomes. At least eight broad interpretations of illness have been identified: challenge, enemy, punishment, weakness, relief, irreparable loss/damage, value adding, and denial (Lipowski 1970; Dunning 1994; Dunning & Martin 1998). In addition, the author has identified other explanatory models as part of routine clinical care: diabetes as an opportunity for positive change; diabetes is a visitation from God.

Care models

Wagner et al. (2002) suggested many care models have limited effectiveness and reach because they rely on traditional education methods and do not support self-management, and transition among services. The essential elements needed to improve outcomes encompass:

- Evidence-based planned care including management guidelines and policies.

- Appropriate service and practice design that encompasses prevention and expedites referral and communication among services.

- Systems to support self-management.

- Process to ensure practitioners are knowledgeable and competent, collaborate and communicate effectively, have sufficient time to provide individual care and are supported to do so and where health professional roles are clearly defined and complementary.

- Clinical information systems that enable disease registries to be maintained, outcomes to be monitored, relevant reminders to be sent to patients and performance to be evaluated (Wagner et al. 1996).

Many current diabetes management models such as the Lorig and Flinders Models, the Group Health Cooperative Diabetes Roadmap, Kaiser-Permanente in Colorado, nurse-led case management, and various shared care models including computer programs (Interactive Health Communication Applications (IHCA)) encompass these elements and improve patient adherence to management strategies and satisfaction. However, their application is still limited by time and resource constraints, including timely patient access to health professionals.

Preliminary research suggests Internet-based support can improve patient–practitioner communication and collaboration, and enhance patient’s sense of being valued and secure (Ralston et al. 2004). However, more research is needed to determine the best way to use these programmes and their effects in specific patient groups (Murray et al. 2005). Generally, patients have a better understanding of what is expected of them if they receive both written and verbal information (Johnson et al. 2003). The font size, colour and language level of any written material provided including instructions for procedures and appointments and health professional contact details needs to be appropriate to the age, education level, and culture of the individual concerned (see Chapter 16).

In addition, health professionals must clearly promote a patient-centred approach care (National Managed Care Congress 1996) that is evident within the service. For example, patients are involved in decisions about their care and see the same doctor each time they attend an appointment. Although patient-centred care is difficult to define and achieve, often because of time constraints, it encompasses ways to:

- achieve personalised care

- ensure care is culturally sensitive and relevant

- increase patient trust in health professionals (Wagner et al. 1996a)

- help patients acquire the information they need to make informed decisions (McCulloch et al. 1998)

- improve patient adherence to management recommendations (Wagner et al. 1996b): also see Chapters 15 and 16.

- make collaborative decisions.

Specific programs that train health professionals how to deliver patient-centred care improve patient trust in doctors (Lewin et al. 2001; McKinstry et al. 2006), and the delivery of patient information (Kinnersley et al. 2007). In addition, patients may need specific education about how to ask relevant questions during consultations, and how to participate in making management decisions. Both parties may need education about how to negotiate the complex nature of shared decision-making to balance the imperative for evidence-based care with the need to incorporate the individual’s values and preferences (Kilmartin 1997). In order to assist the process, the Foundation for Informed Decision-Making in the USA (2007) developed a series of interactive videos and written materials for patients about a range of common medical conditions.

In order to meet these requirements it is necessary to undertake a thorough assessment, use clinical reasoning to identify the patient’s needs and management guidelines to determine whether the recommended treatment is likely to benefit the individual, whether the benefits outweigh the risks, and whether the individual can/will adhere to the recommendations including their self-care capacity, and then select the most appropriate treatment option.

Characteristics of an holistic nursing history

The nursing history

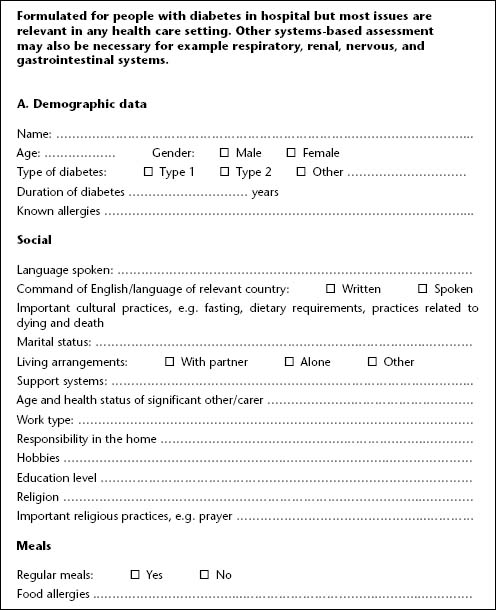

- Includes demographic data (age, gender, social situation).

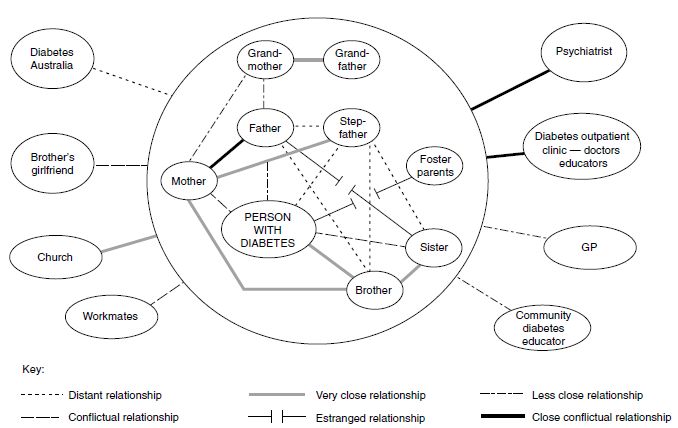

- Collects units of information about past and current individual and family health and family and social relationships (see Figure 2.1) to permit individual care plans to be formulated considering the person’s goals and expectations.

- Obtains baseline information about the person’s physical and mental status before and after and the presenting complaint.

- Collects information about the person’s general health and diabetes-related beliefs and attitudes and the meaning they attach to, and the importance they place on symptoms.

- Obtains baseline information about the person’s physical and mental status before and after and the presenting complaint.

- Should be concise to enable information to be collected in a short time.

- Should focus on maintaining the person’s independence while they are in hospital (e.g. allowing them to perform their own blood glucose tests).

Figure 2.1 Example of a combination of a genomap (information inside the circle) and an ecomap (information outside the circle) of a 50-year-old woman with Type 2 diabetes and a history of childhood molestation and sexual abuse. It shows a great deal of conflict within and outside the family and identifies where her support base is.

The findings should be documented in the patient record and communicated to the appropriate caregivers. There is an increasing trend towards electronic data collection and management process that enable information to be easily and rapidly transferred among health professionals. Some systems enable patients to access their health information. Most modern electronic blood glucose meters have a facility for marinating a record of blood glucose test result that can be downloaded into computer programs. These systems have the capacity to significantly improve health care, however, consideration must be given to the privacy and confidentiality of all personal information and appropriate access and storage security mechanisms should be maintained according to the laws of the relevant country

Note: A guideline for obtaining a comprehensive nursing history follows. However, it is important, to listen to the patient and not be locked into ‘ticking boxes’, so assumptions can be checked and non-verbal messages and body language noted and clarified, so that vital and valuable information is not overlooked.

Most of the information is general in nature, but some will be specifically relevant to diabetes (e.g. blood glucose testing and eating patterns). The clinical assessment in this example is particularly aimed at obtaining information about metabolic status.

Assessment of the person with diabetes does not differ from the assessment performed for any other disease process. Assessment should take into account social, physical and psychological factors in order to prepare an appropriate nursing care plan, including a plan for diabetes education and discharge/transition.

Any physical disability the patient has will affect their ability to self-manage their diabetes (inject insulin, inspect feet, test blood glucose). Impaired hearing and psychological distress and mental illness may preclude people attending group education programmes. Management and educational expectations may need to be modified to take any disability into account.

If the person has diabetes, however, metabolic derangements may be present at admission, or could develop as a consequence of hospitalisation. Therefore, careful assessment enables potential problems to be identified, a coordinated collaborative care plan to be developed and appropriate referral to other health professionals (medical specialist, podiatrist, diabetes nurse specialist/diabetes educator, dietitian, psychologist) to take place. A health ‘problem list’, that ranks problems in order of priority can also assist in planning individualised care that addresses immediate and future management goals. The first step in patient assessment is to document a comprehensive health history.

Nursing history

A nursing history is a written record of specific information about a patient. The data collected enables the nurse to plan appropriate nursing actions considering individual patient’s worldviews and needs. A good patient care plan will enable consistent care to be delivered within, and among, service departments. An example patient assessment chart follows. It was formulated to collect relevant diabetes-specific data, which could be used in conjunction with other relevant tools such as those shown in Table 2.1. Some electronic data management systems enable some information to be collected electronically from existing records when the patient has attended the service before.

Example health assessment chart