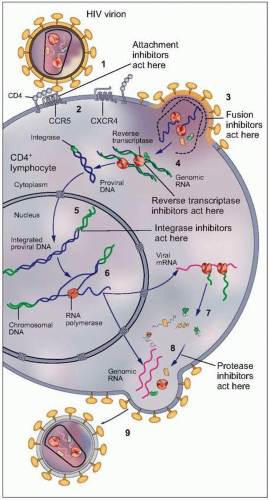

CD4+ T cell destruction. Among these, defects in B cell proliferation and antibody production, impaired cytotoxic lymphocytic responses, decreased dendritic cell number and function, and profound perturbations of the cytokine milieu have all been shown, particularly in advanced stages of HIV infection. The precise mechanism by which HIV infection leads to these wide-ranging defects is incompletely understood, although they are related to HIV replication, and can be partially corrected by effective antiretroviral therapy that suppresses plasma viremia to very low levels. The vital cycle of HIV is complex and includes multiple steps that can be targeted for therapeutic purposes. These steps are summarized in Fig. 1.3.

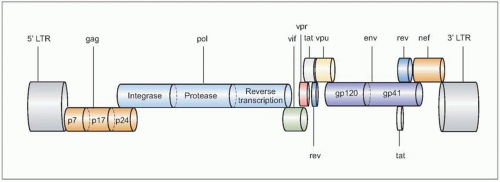

Fig. 1.1 The genomic organization of HIV. The complete genome is approximately 10 kb in size, and is similar to the general structure of other retroviruses. In the figure, the most relevant genes are represented in different colors, and the most important proteins they encode for are shown inside the corresponding symbols. Not all gene products are shown. |

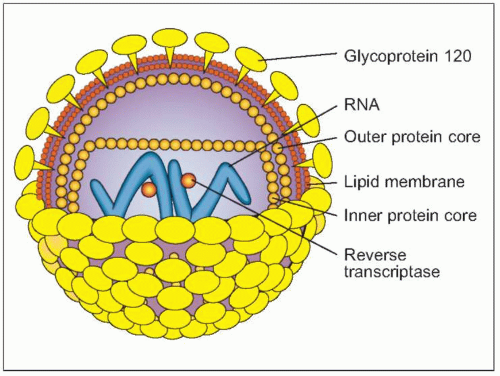

Fig. 1.2 Schematic view of HIV structure. |

Fig. 1.3 Vital cycle of HIV and sites targeted by current anti-HIV medications. After HIV binds to its primary receptor, CD4 (1), the viral envelope undergoes a conformational change that facilitates binding to another cellular coreceptor, the most important of which are the chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4 (2). Interaction with the coreceptor triggers further conformational changes in the envelope that bring the viral and cellular membranes into close proximity, thereby permitting their fusion (3) through insertion of the newly exposed fusion domain of the envelope protein gp41 into the host cell membrane. The HIV nucleocapsid then enters the cytoplasm, where the RNA genomic material of the virus is reverse transcribed into DNA (4) by the virally encoded reverse transcriptase. Next, the double-stranded viral DNA enters the nucleus, where it integrates into the host genome with the aid of the HIV-encoded enzyme integrase (5). The integrated proviral DNA is then transcribed into messenger RNA (6), which serves as the template for assembly of the main viral structural proteins (7). The protein complex is cleaved by a protease into functional segments (8), thus allowing assembly and budding of the new viral particles (9) to proceed. |

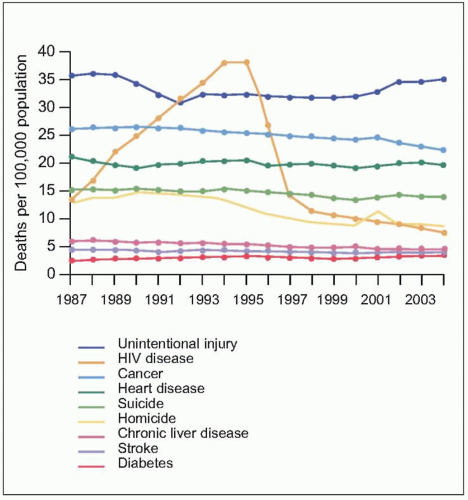

Fig. 1.5 Trends in annual rates of death due to the nine leading causes among persons 25-44 years old, USA, 1987-2004. HIV disease was the leading cause of death among person 25-44 years old in 1994 and 1995. With the introduction of HAART in 1995, the rank of HIV disease fell to 5th place from 1997 through 2000, and to 6th place in 2001 and 2002. The spike in the death rate due to homicide in 2001 resulted from the terrorist attack on September 11. (Adapted from CDC data.) |

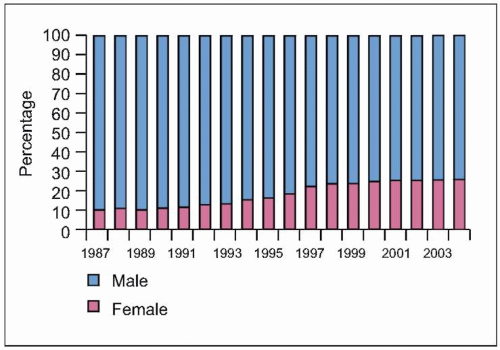

Fig. 1.6 Trends in the percentage distribution of deaths due to HIV disease by sex, USA, 1987-2004. The proportion of females among persons who died of HIV disease increased from 10% to 26% during this period, highlighting the increasing burden of disease among females in the US, as is the case in other countries. Because heterosexual transmission is emerging as the predominant mode of transmission, this trend can be expected to grow in the coming years. (Adapted from CDC data.) |

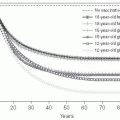

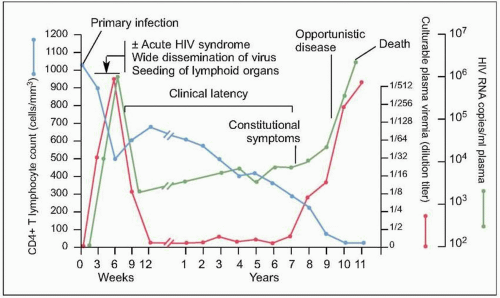

Fig. 1.7 Natural history of untreated HIV disease. Shortly after infection, viremia reaches extremely high levels, while CD4+ count decreases to levels that may be sufficient for the development of certain opportunistic complications. During this period, patients may experience the manifestations of the acute retroviral syndrome, and are highly infectious, thus making a high index of suspicion of paramount importance. After this initial phase, viremia decreases to a level (referred to as ‘set point’) at which it will remain, relatively constant, during the subsequent phase. At the same time, CD4+ T cell count rebounds, but does not return to pre-infection levels. A relatively asymptomatic period follows, during which there is ongoing viral replication and a slow but demonstrable decline in CD4+ T cell count. This phase ends years after infection with a precipitous fall in CD4+ T cell count and an exponential rise in plasma HIV RNA level, which heralds the beginning of AIDS. (Adapted from Fauci AS, Pantaleo G, Stanley S, et al. Immunopathic mechanisms of HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:654.) |

occur at later stages. A useful classification that includes both clinical and laboratory markers is the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) staging system, shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.1 Clinical manifestations of acute retroviral syndrome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 1.2 US Centers for Disease Control 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection in adults and adolescents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Fig. 1.8 Maculopapular rash consistent with acute HIV infection. |

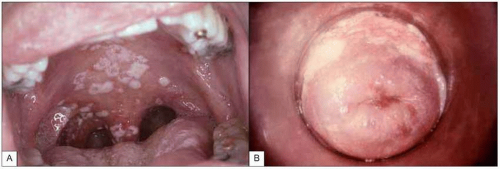

Fig. 1.9 Mucosal candidiasis in moderately advanced HIV infection. A:Thrush (oropharyngeal candidiasis). Typical white exudates that can be removed with a tongue depressor are seen covering the oral mucosa. B: Vaginal candidiasis. The similarity of the exudates covering the vaginal wall is obvious. (A: courtesy of Dr S Silverman, CDC; B: courtesy of CDC.) |

Fig. 1.10A, B Multidermatomal herpes zoster (shingles) in a patient with advanced HIV infection and incomplete CD4+ T cell replenishment after highly active antiretroviral therapy. Note the characteristic erythematous-vesicular rash that does not cross the midline and involves several dermatomes. Some of the lesions have begun to crust, while others (e.g. on the upper arm) are in a pustular phase. |

Fig. 1.11 Oral hairy leukoplakia. This lesion is associated with Epstein-Barr infection of the keratinized epithelium of the tongue and the buccal mucosa, and can be distinguished from oral candidiasis by the characteristic location on the lateral surface of the tongue, its resistance to scraping with a tongue depressor and its failure to respond to antifungal therapy. OHL can be seen at relatively early stages of HIV disease, but its prevalence increases with decreasing CD4+ T cell counts. (Courtesy of Dr S Silverman, DDS.) |

Fig. 1.12 Cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis in a Ugandan patient with AIDS. This person was not known to be HIV infected when he presented to the TB clinic complaining of subacute respiratory symptoms, fevers, and diaphoresis. Note the characteristic right upper lobe location of the lesion, and the air-fluid level, indicative of a cavitating lesion in that location. At the time of this visit, the patient’s CD4+ T cell count was approximately 400 cell/mm3. |

frequency increases with progressive immunodeficiency. The risk of bacterial pneumonia is up to 100-fold greater in HIV infection. Other encapsulated organisms such as Hemophilus influenzae and highly virulent pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa are also more common in HIV-infected patients. Pneumococcal pneumonia typically presents with a similar clinical picture to that in HIV-negative patients (Figs. 1.16, 1.17), but mortality is increased in HIV-infected patients, particularly with advanced disease, when atypical presentations including subtle interstitial infiltrates and a protracted course reminiscent of Pneumocystis jirovecii can be seen. Concomitant bacteremia is especially common in this setting, making blood cultures an important part of the diagnostic evaluation. Nodular and cavitary lesions, in addition to mycobacterial and fungal disease, should raise suspicion for less common bacterial pulmonary pathogens including Nocardia species (Fig. 1.18) and Rhodococcus equi, particularly in the setting of clinical manifestations in other organ systems (Fig. 1.19).

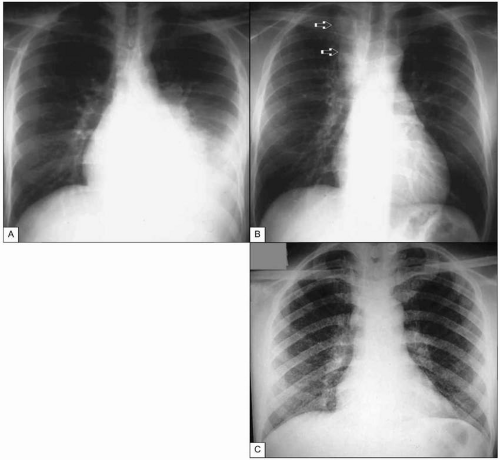

Fig. 1.13 Tuberculosis in advanced AIDS. A: Pleural tuberculosis. This massive pleural effusion resolved completely after anti-TB treatment. B: Tuberculous adenitis. This mass (arrows) can easily be mistaken for a neoplasia, leading to unnecessary interventions. C: Miliary tuberculosis in a patient with advanced AIDS. Note the finely micronodular infiltrate involving virtually all the pulmonary parenchyma. CD4+ T cell count at the time of diagnosis was <5 cells/mm3. (A and B courtesy of Dr R Kalayjian.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|