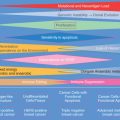

Abstract

This chapter provides the reader with an overview of the key milestones in the development of the current understanding and management of breast cancer. Although the milestones listed here are important ones, the list is by no means comprehensive. The historical evolution of breast cancer treatment begins with the ancient civilizations, moves through the Middle Ages, and the 18th and 19th centuries and broadly covers the advent of breast reconstruction, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and advances in cancer biology during the 20th century through current therapies.

Keywords

history, breast cancer, management

With their uncertain etiology, breast diseases have captured the attention of physicians throughout the ages. Despite centuries of theoretical meanderings and scientific inquiry, breast cancer remains one of the most dreaded of all human diseases. The historical account of the efforts to cope with breast cancer is complex, and there is no definitive causation as there is in diseases for which cause and cure have been defined. However, progress has been made in lessening the horrors that formerly devastated the body and psyche.

This chapter was developed to examine the history of breast diseases/cancer. It records key milestones in the development of the current progress of the biology and therapy of these presentations, which is based on the achievements and contributions of multiple physicians and scientists over many hundreds of years. Although the milestones listed here are important ones, the list should not be considered comprehensive. This chapter is meant to be a useful reference to all who desire knowledge of the historical background of breast cancer and that of evolving breast cancer therapy.

Ancient Civilizations

Chinese

Huang Di, the Yellow Emperor, was born in 2698 bce and subsequently wrote the Nei Jing, the oldest treatise of medicine, which gives the first description of tumors and documents five forms of therapy: spiritual care, pharmacology, diet, acupuncture, and the treatment of specific diseases.

Egyptian

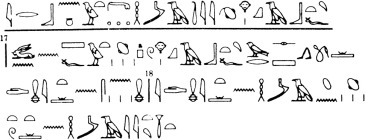

Imhotep, an Egyptian physician, architect, and astrologer, was born in 2650 bce . He designed the first pyramid at Saqqara and was deified as the god of healing. The early Egyptians documented many cases of breast tumors, which were treated with cautery. To preserve their findings, the Egyptians etched their cursive script on thin sheets of papyrus leaf and also engraved or painted hieroglyphics on stone. Among six principal papyri, the most informative one with respect to diseases of the breast is that acquired by Edwin Smith (b. 1822) in 1862 and presented to the New York Historical Society at the time of his death. Dating to about 1600 bce , it is a papyrus roll 15 feet long, with writing on both sides. The front contains 17 columns describing 48 cases devoted to clinical surgery. References are made to diseases of the breast such as abscesses, trauma, and infected wounds. Case 45 is perhaps the earliest record of breast cancer, with the title Instructions Concerning Tumors on the Breast ( Fig. 1.1 ). The examiner is told that a breast with bulging tumors, very cool to the touch, is an ailment for which there is no treatment.

Babylonian

The Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1750 bce ) was commissioned in Babylon. Its 282 clauses provided the first laws that regulated medical practitioners and dealt with physicians’ responsibilities and fees. At that time, internal medicine consisted mainly of a recitation of litanies and incantations against the demons of the earth, air, and water. Surgery consisted of opening an abscess with a bronze lancet. If the patient died or lost an eye during treatment, the physician’s hands were cut off.

Classic Greek Period (460–136 bce)

Medicine in Europe had its origins in ancient Greece. The scientific method and clinical advancement of medicine are credited to Hippocrates (b. 460 bce ), who also defined its ethical ideals. His basic philosophy was the linkage of four cardinal body humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) with four universal elements (earth, air, water, and fire). Perfect health depended on a proper balance in the dynamic qualities of the humors. It was generally believed that blood was in the arteries and veins, phlegm in the brain, yellow bile in the liver, and black bile in the spleen. Hippocrates divided diseases into three general categories: those curable by medicine (most favorable), those not curable by medicine but curable by the knife, and those not curable by the knife but curable by fire. The Corpus Hippocraticum deals with the treatment of fractures, tumors, surgical procedures, asthma, allergies, and diseases of the skin. A well-documented case history of Hippocrates describes a woman with breast cancer associated with bloody discharge from the nipple. Hippocrates associated breast cancer with cessation of menstruation, leading to breast engorgement and indurated nodules.

Alexandria on the Nile, founded by Alexander the Great in 332 bce , became the focal point of Greek science during the third and second centuries bce . More than 14,000 students studied various elements of Hellenistic knowledge there. This knowledge was contained in 700,000 scrolls in the largest library in antiquity, which was subsequently destroyed by Julius Caesar. Rudimentary anatomic studies were conducted and led to progress in the tools and techniques of surgery.

Greco-Roman Period (150 bce–ad 500)

After the destruction of Corinth in 146 bce , Greek medicine migrated to Rome. During the preceding six centuries, the Romans had lived without physicians. They depended on medicinal herbs, assorted concoctions, votive objects, religious rites, and superstitions ( Fig. 1.2 ).

Aurelius Celsus, a Roman born in 25 bce , described the cardinal signs of inflammation (calor, rubor, dolor, and turgor). He wrote De Medicina around ad 30, which contains an early clinical description of cancer and likened the lesion to a crab. In it he notes that breasts of women as one of the anatomic sites of cancer and describes a fixed irregular swelling with dilated tortuous veins and ulceration. He also delineates four clinical stages of cancer: (1) early cancer, cacoethes; (2) cancer without ulcer; (3) ulcerated cancer; and (4) ulcerated cancer with cauliflower-like excrescences that bleed easily. Celsus strongly advised against the treatment of the last three stages by any method because aggressive measures irritated the condition and led to inevitable recurrence.

The Greek physician Leonides is credited with the first operative treatment for breast cancer in the first century ad . His method consisted of an initial incision into the uninvolved portion of the breast, followed by applications of cautery to stop the bleeding. Repetitive incisions and applications of cautery were continued until the entire breast and tumor had been removed and the underlying tissues were covered with an eschar. With Roman influence and support, surgical instruments became highly specialized, as witnessed by the finding of more than 200 different instruments in the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum ( Figs. 1.3 and 1.4 ).

The greatest Greek physician to follow Hippocrates was Galen (b. ad 131). He was born on the Mediterranean coast of Asia Minor, studied in Alexandria, and practiced medicine for the remainder of his life in Rome. He is credited as the founder of experimental physiology, and his system of pathology followed that of Hippocrates.

Galen considered black bile, especially when it was extremely dark or thick, to be the most harmful of the four humors and the ultimate cause of cancer. He described breast cancer as a swelling with distended veins resembling the shape of a crab’s legs. To prevent accumulation of black bile, Galen advocated that the patient be purged and bled. He claimed to have cured the disease in its early stage when the tumor was on the surface of the breast and all the “roots” could be extirpated at surgery. The roots were not derived from the tumor but were dilated veins filled with morbid black bile. When removing these superficial (anterior) lesions, the surgeon had to be aware of the danger of profuse hemorrhage from large blood vessels. On the other hand, the surgeon was advised to allow the blood to flow freely for a while to allow the “black bile” (blood) to escape.

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages may be considered the period between the downfall of Rome and the beginning of the Renaissance. The doctrine of the four humors, which formed the basis of Hippocratic medicine, was endowed with authority by Galen and governed all aspects of medical thinking throughout and beyond the Middle Ages. This influence can be traced in the Christian, Jewish, and Arabic traditions.

Christian

From the Christian standpoint, the monks and clerics who constituted the educated class maintained medicine in the Middle Ages. In 529, with the founding by Saint Benedict of the Monastery on Monte Cassino in central Italy, there arose a heightened interest in medicine in the scattered cloisters of the Roman Church. Monte Cassino fostered the teaching and practice of medicine, along with the copying and preserving of ancient manuscripts. Many satellite monasteries developed throughout Christendom in which the monks treated the sick and copied medical manuscripts. Subsequently, monastic schools spread under the Benedictines to England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Switzerland, and most of the European continent. The patron saint for breast disease was Saint Agatha . She had been a martyr in Sicily in the middle of the third century when her two breasts were torn off with iron shears because of resistance to the advances of the governor Quinctianus ( Fig. 1.5 ). On Saint Agatha’s day, two loaves of bread representing her previously mutilated breasts are carried in procession on a tray.

The Council of Rheims (1131) excluded monks and the clergy from the practice of medicine. From that time on, laymen increasingly preserved the tradition of medical teaching and practice. Cathedral schools, although in clerical hands, profited from greater freedom than the monasteries had provided and enjoyed the intellectual contacts of the large cities. Further growth of cities in the 11th and 12th centuries led to the rise of universities with academic approaches to science; this movement freed the teaching and control of medicine from monastic influence.

Paul of Aegina (b. 625) was an Alexandrian physician and surgeon famed for his Epitomae Medicae Libri Septem, which contained descriptions of trephining, tonsillotomy, paracentesis, and mastectomy. Lanfranc of Milan (b. 1250) was an Italian surgeon who worked in Paris and wrote Chirurgia Magna, which contained sections on anatomy, embryology, ulcers, fistulas, and fractures, as well as sections on herbs and pharmacy and on cancer of the breast.

Jewish

Jewish physicians were active at Salerno, Italy, as early as the ninth century. They achieved great distinction not only in the art of healing but also in their literary efforts. Popes, kings, and noblemen sought their services. In a time when poisoning of enemies and rivals was common, the Jews were considered the safest medical advisers. The Arabian rulers and Egyptian caliphs also preferred them to their Mohammedan physicians, who practiced magic and astrology in their treatment of disease.

Under the tolerant Moors of Spain and the early Christian rulers of Spain and Portugal, the Jews became leaders in the medical profession. The foremost among them was Moses Maimonides. Born in Cordova, Spain, in 1135, he studied medicine at Cairo and became the physician to Saladin, the Sultan of Egypt. In addition to his own medical treatise, he translated from Arabic into Hebrew the five volume al-Quanum fil-Tib of the Iranian physician Avicenna (b. 980), which was the authoritative encyclopedia of medicine during the Middle Ages. Maimonides also made a collection of the aphorisms of Hippocrates and Galen.

Jewish physicians remained prominent in Spain under the Western Caliphate until they were banished from the country in 1492. The Salerno School exploited them as teachers until it had enough indigenous talent to proceed without them. Even at Montpellier in southern France, the Jews were excluded in 1301. It would not be until the onset of the modern industrial age that they would again be admitted to citizenship throughout Europe and given university freedom, which once more liberated their brilliant medical talent.

Arabic

Western society is indebted to Arabic scholars and physicians who valued and preserved the teachings and writings of their Greek predecessors. Without the intervention of the Arabs, the writings of the Greek physicians might have been lost. Baghdad, the capital of the Islamic Empire in Iraq, became the center for translation of the Greek authors. The library at Cordova had 600,000 manuscripts, and the one at Cairo had 18 rooms of books. The Tartars raided the library in Baghdad in 1260 and threw the books into the river.

Rhazes (b. 860), one of the great Arabic physicians, condoned excision of breast cancer only if it could be completely removed and the underlying tissues cauterized. He warned that incising a breast cancer would produce an ulceration. Haly ben Abbas, a Persian who died in 994, authored an encyclopedic work in medicine and surgery based on Rhazes and the Greek sources. He endorsed the removal of breast cancers with allowance for bleeding to evacuate melancholic humors, which were widely believed to predispose to cancer. He did not tie the arteries and made no notation of wound cautery. Avicenna was the successor to Haly ben Abbas and was known as the “Prince of Physicians.” He was chief physician to the hospital at Baghdad and was the author of a vast scientific and philosophical encyclopedia, Kitab-Ash-shifa, as well as the al-Quanum fil-Tib, both of which remained authoritative references for centuries.

Renaissance

The transition from the medieval to the modern era occurred in the latter part of the 15th century, with the introduction of gunpowder into warfare, the discovery of America, and the invention of the printing press. During this period, medical teaching flourished in universities in Montpellier, Bologna, Padua, Paris, Oxford, and Cambridge.

Andreas Vesalius (b. 1514) was a Flemish physician who revolutionized the study of medicine with his detailed descriptions of the anatomy of the human body, based on his own dissection of cadavers. His masterful observation and anatomic descriptions and illustrations were instrumental in opening scientific query and pathologic anatomy in medical science. While at the University of Padua, he wrote and illustrated the first comprehensive textbook of anatomy, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (1543). He recommended mastectomy for breast cancer and the use of sutures rather than cautery to control bleeding.

Ambrose Paré (b. 1510) studied medicine in Paris and, through his war experience, became the greatest surgeon of his time. His conservative surgical approach to cancer was detailed in Oeuvres Complètes (1575). He encouraged the use of vascular ligatures and the avoidance of cautery and boiling oil. He supported the excision of superficial breast cancers but attempted to treat advanced breast cancers through application of lead plates, which were intended to compress the blood supply and arrest tumor growth. He made the important observation that breast cancer often initiated enlargement of the axillary “glands.” Michael Servetus (b. 1509), a Spaniard who studied in Paris, was burned at the stake for his heretical discovery that blood in the pulmonary circulation passes into the heart after having been mixed with air in the lungs. For cancer of the breast, Servetus suggested that the underlying pectoralis muscles be removed en bloc, together with the axillary glands, as described by Paré. This recommendation predated, by nearly four centuries, the anatomic basis of the radical mastectomy espoused by Halsted and Meyer.

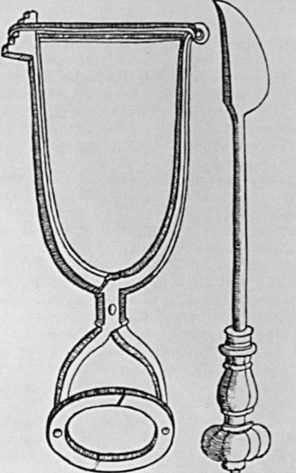

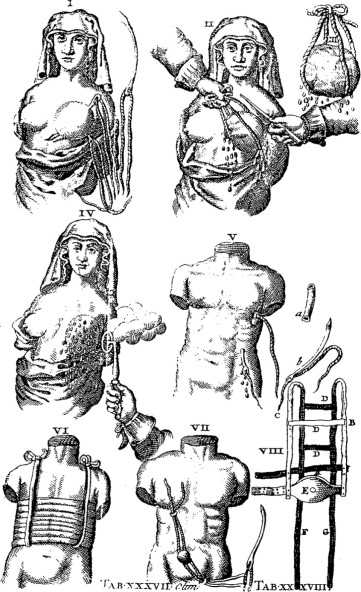

Wilhelm Fabry (b. 1560) is held in esteem as the “Father of German Surgery.” His name was honored by the placement of a wreath at his statue in Hilden near Düsseldorf, Germany, by members of the International Society of the History of Medicine in 1986 ( Fig. 1.6 ). He devised an instrument ( Fig. 1.7 ) that compressed and fixed the base of the breast so that a scalpel could amputate it more swiftly and less painfully. His text, Opera, included clear descriptions of breast cancer operations and illustrations of amputation forceps. He stipulated that the tumor should be mobile so that it could be removed completely, with no remnants left behind. The other famous German surgeon of this period was Johann Schultes (b. 1595), known as Scultetus, who was an illustrator of surgery and inventor of surgical instruments. His book, Armamentarium Chirurgicum, which was published posthumously in 1653, contained illustrations of surgical procedures, one of which represented amputation of the breast. He used heavy ligatures on large needles, which transfixed the breast so that traction would facilitate its removal by the knife. Hemostasis was secured by cauterization of the base of the tumor ( Fig. 1.8 ).

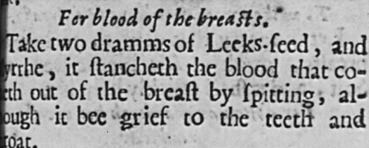

Because of the morbidity and mortality of breast cancer surgery and a paucity of competent surgeons, few breast amputations were actually performed. Nonsurgical remedies for breast cancer appeared in rudimentary scientific journals that were published toward the end of the 17th century ( Fig. 1.9 ).

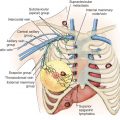

Eighteenth Century

The 1700s were slow to develop significant new concepts in pathology and physiology. The arbitrary separation of scirrhus and breast cancer in the doctrine of Galen was still thought to be correct. Many considered scirrhus to be a benign growth that under adverse circumstances could undergo malignant degeneration, whereas others regarded it as an existing stage of cancer. Most believed that scirrhus originated in stagnation and coagulation of body fluids within the breast (local cause). Others believed it to occur from a general internal derangement of the body juices (systemic cause). In accepting both causes, some authors wrote that the local cause could be a precipitating factor in a predisposed patient. Hermann Boerhaave (b. 1668) taught that Galen’s yellow bile was blood serum rather than bile itself, that phlegm was serum that had been altered by standing, and that black bile was a part of a clot that had largely separated and had a darkened coloration. Thus the four humors of Galen were only different components of the blood. Pieter Camper (b. 1722) described and illustrated the internal mammary lymph nodes, and Paolo Mascagni (b. 1752) did the same for the pectoral lymph nodes. Death caused by metastasis from breast cancer was not yet understood. If death was not caused by hemorrhage, it was ascribed to a general decomposition of the humors.

The surgeon Henri François Le Dran (b. 1685) of France ( Fig. 1.10 ) concluded that cancer was a local disease in its early stages and that its spread to the lymphatic system signaled a worsened prognosis. This was a courageous contradiction to the humoral theory of Galen, which had persisted for a thousand years and was to be upheld by many for two centuries to come. A colleague of Le Dran, Jean Petit (b. 1674), first director of the French Academy of Surgery, supported these principles. As recommended by the martyred Servetus, Le Dran also advocated en bloc removal of the breast, the underlying pectoral muscle, and the axillary lymph nodes. Petit removed skin directly involved by cancer but returned skin closure over the noninvolved breast. In his book, Traites des Operations, which was not published until 24 years after his death, Petit recommended total removal of the breast and any enlarged axillary lymph nodes, as well as the pectoralis major muscle if it was involved by cancer. He asserted, “the roots of a cancer were the enlarged lymphatic glands.” Although Petit recognized the necessity of removing any skin directly involved by a breast cancer, he advised leaving most of the overlying skin, including the nipple, and dissecting breast tissue out from beneath it.

Petit’s pupil and colleague, Rene Garangeot (1688–1760), was largely responsible for preserving and disseminating the teachings of Petit. Garangeot explained the rationale for skin preservation in his book, Traites des Operations de Chirurgie (1720):

Sewing up the lips of the wound immediately after operation, as was practiced by J.L. Petit, is not only the safest method of arresting hemorrhage but is also the quickest way of healing the wound and preventing the return of the cancer.

Lorenz Heister (1683–1758), a famous German surgeon, used a guillotine device to amputate the entire breast. He was aware of the prognostic implications of axillary lymph node enlargement. In conjunction with mastectomy, he recommended removal of axillary lymph nodes, the pectoralis major muscle, and portions of the chest wall, if necessary, for complete excision of the cancer. Another French surgeon, Bernard Peyrilhe (1735–1804), embraced the concept that breast cancer began locally and spread by way of the lymphatics. Peyrilhe unsuccessfully attempted to transmit cancer by injecting human breast cancer tissue into dogs. Following the practice of Petit and Heister, Peyrilhe advocated total mastectomy along with removal of the axillary lymph nodes and the pectoralis major muscle.

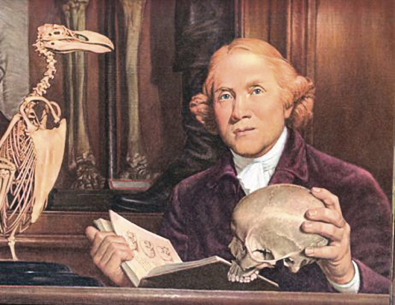

In Edinburgh, Scotland, which was strongly oriented to university teaching, the separation of surgeons from barbers occurred by 1718. In London, where barber-surgeon guilds had existed, the separation occurred in 1745. A new era of British surgery began when William Cheselden (b. 1688), surgeon to St. Thomas’ and St. George’s Hospitals, first established private courses in anatomy and surgery. The Hunter brothers, John (b. 1728) and William (b. 1718), of Scotland followed suit. These courses attracted students from all over the country, the continent, and America. John Hunter is credited as being the founder of experimental surgery and surgical pathology ( Fig. 1.11 ).

Samuel Sharpe, an English surgeon, advocated an approach similar to those of Petit, Heister, and Peyrilhe in his Treatise on the Operations of Surgery, which was published in 1735. For small cancers, he recommended removing the entire breast through a longitudinal incision. However, for larger cancers, he recommended removing an oval segment of skin to facilitate the mastectomy. He claimed that mastectomy was impractical if the breast cancer involved the underlying pectoral muscles but removed any “knobs” in the axilla.

Benjamin Bell (1749–1806), surgeon at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, advocated a radical surgical procedure for all breast cancers and emphasized the importance of early diagnosis. He echoed Petit’s views in his book A System of Surgery (1784) :

When practitioners have an opportunity of removing a cancerous breast early, they should always embrace it, that as little skin as possible should be removed, and that the breast should be dissected off the pectoral muscle, which ought to be preserved. If any indurated glands be observed, they should be removed and particular care should be given to this part of the operation. For unless all the diseased glands be taken away, no advantage whatever will be derived from it.

Henry Fearon (1750–1825), a British surgeon, recognized the importance of early detection and treatment of breast cancer but acknowledged the difficulties inherent in such an approach. In 1784 he wrote, “the early period of the complaint is beyond all doubt the most favorable period for extirpating it, however patients can seldom be convinced that there is any necessity for an operation while the disease continues in a mild state.”

In the late 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, pessimism toward breast cancer pervaded the medical literature, primarily as a result of the poor outcome after radical breast cancer surgery. The first hospital ward for indigent cancer patients opened in Middlesex Hospital in London in 1792 with the acknowledgment that it provided an opportunity to study the natural history of breast cancer. In 1757, Petrus Camper commented on the reluctance of most of the surgeons in Amsterdam, which had a population of 200,000, to perform a mastectomy for breast cancer: “not six times a year a breast was amputated with reasonable chance of cure.” Large numbers of mastectomies were performed during the early 18th century, but this number decreased during the second half of the century because of poor results and the indiscriminate mutilation that occurred with improper patient selection and physician bias.

Alexander Monro Senior (1697–1767) reviewed 60 patients with breast cancer who underwent a mastectomy and found that only 4 of these patients were free of cancer after 2 years. Operative mortality, primarily from sepsis, was reported to be as high as 20%. In 1842, the Scottish surgeon James Syme (1799–1870) wrote in his Principles of Surgery that surgical procedures for breast cancer should be abandoned when axillary lymph nodes were involved or when the cancer was too large for complete removal. He found that surgery was likely to “excite greater activity” from the cancer that was left behind, echoing the comments of Celsus nearly 1900 years earlier.

In 1856, Sir James Paget (1814–1899) wrote that breast cancer was so hopeless that the mortality and morbidity associated with its treatment could not be justified. He reported that women with “scirrhous” breast cancer lived longer if they avoided surgical intervention. On reviewing his 235 breast cancer cases, Paget reported no cures and an 8-year recurrence rate of 100%.

Nineteenth Century

Breast surgery changed dramatically in the 1800s. William Morton introduced anesthesia in the United States in 1846 at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and Joseph Lister introduced the principle of bacterial antisepsis in England in 1867. Lister implemented its transfer and development to operating theaters throughout Europe and America. These two pivotal advances were responsible, in part, for this dramatic change in surgical management and outcomes.

European Surgery

At the beginning of the 19th century, the treatment for breast cancer remained in the status quo. In 1811 Samuel Young in England revived the method of Paré, in which compression was used to cut off the blood supply of the tumor. Nooth, another English surgeon, sprayed the breast with carbolic acid, which was a modified form of the ancient practice of cauterization.

James Syme (b. 1799) was a famous Scottish surgeon. His daughter married Sir Joseph Lister. Much of Syme’s breast surgery was performed before the use of anesthesia. His third surgical apprentice, John Brown (b. 1810), wrote Rab and His Friends (1858), which contains a vivid description of breast surgery as performed by the then 28-year-old Syme in the Minto House Hospital of Edinburgh, Scotland :

The operating theater is crowded; much talk and fun and all the cordiality and stir of youth. The surgeon with his staff of assistants is there. In comes Ailie [the patient]: one look at her quiets and abates the eager students. Ailie stepped upon a seat, and laid herself on the table, as her friend the surgeon told her; arranged herself, gave a rapid look at James [her husband], shut her eyes, rested herself on me [Brown], and took my hand. The operation was at once begun; it was necessarily slow; and chloroform—one of God’s best gifts to his suffering children—was then unknown. The surgeon did his work. The pale face showed its pain, but was still and silent. Rab’s [the family’s dog, a mastiff] soul was working within him; he saw that something strange was going on—blood flowing from his mistress, and she suffering; his ragged ear was up, and importunate; he growled and gave now and then a sharp impatient yelp; he would have liked to have done something to that man. But James had him firm, and gave him a glower from time to time, and an intimation of a possible kick—all the better for James, it kept his eye and his mind off Ailie. It is over: she is dressed, steps gently and decently down from the table, looks for James; then turning to the surgeon and the students, she curtsies—and in a low, clear voice, begs their pardon if she has behaved ill. The students—all of us—wept like children; the surgeon helped her up carefully—and resting on James and me, Ailie went to her room, Rab following. Four days after the operation what might have been expected happened. The patient had a chill, the wound was septic, and she died.

Later in life Syme was able to operate with the patient under anesthesia. He felt it incumbent on the surgeon to search carefully for axillary glands in the course of the operation but stated that the results were almost always unsatisfactory when the glands were involved, no matter how perfectly they seemed to have been removed. Sir James Paget (b. 1814) reported an operative mortality of 10% in 235 patients and among survivors, recurrence within 8 years. In 139 patients with scirrhous carcinoma, those who did not undergo surgery lived longer than those who did. In 1874 Paget published On Disease of the Mammary Areola Preceding Cancer of the Mammary Gland, which described cancer of the nipple accompanied by eczematous changes and cancer of the lactiferous ducts (Paget’s disease of the breast).

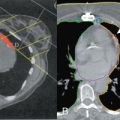

In 1867, Charles Hewitt Moore (b. 1821) of the Middlesex Hospital in London championed the belief that the only possibility of cure for breast cancer was through wider and more extensive surgery, despite the frequent disastrous results ( Fig. 1.12 ). His seminal paper, On the Influence of Inadequate Operation on the Theory of Cancer (1867), was widely accepted. He appropriately stressed that the tumor should not be divided or incised and that recurrences originated as a result of dispersion from the primary growth and were not independent in origin. His operation called for removal of the entire breast, with special attention to removal of the skin in continuity with the main mass of the tumor en bloc with enlarged axillary lymphatics. Moore did not advocate removal of the pectoralis major muscle. In 1858 Moore was the first to advocate placement of drainage tubes through the axilla.

The father of surgical antiseptic technique and one of Great Britain’s most respected surgeons, Sir Joseph Lister (b. 1827) of Edinburgh Scotland, agreed with Moore’s principles and in 1870 advocated division of the origins of both pectoral muscles to gain better exposure of the axilla for the axillary gland dissection. His contribution of carbolic acid spray was not widely accepted for 15 to 20 years. In 1877 Mitchell Banks of Liverpool, England, advocated removal of the axillary glands in all cases of surgery for breast cancer. He washed the wound with carbolic acid solution but avoided the spray because of its cooling effect on the patient.

Alfred-Armand-Louis-Marie Velpeau (b. 1795) of France, originally apprenticed to the blacksmith trade, later rose to become professor of clinical surgery at the Paris Faculty, which was established in 1834. In his Treatise on Diseases of the Breast (1854), he claimed to have seen more than 1000 benign or malignant breast tumors during a practice of 40 years. In those times, once the cancer had been excised, the patient and surgeon parted company and follow-up was scanty. In 1844 Jean-Jacques-Joseph Leroy d’Etiolles (b. 1798) conducted a study of 1192 patients with breast cancer. He concluded that mastectomy was more harmful than beneficial. The 1854 Congress of the Académie de Médecine discussed whether cancer should be treated at all.

Emerging innovative surgical practices developed in Germany in 1875, when Richard von Volkmann (b. 1830) advocated the en bloc resection of the entire breast, no matter the size of the primary tumor. He further recommended resection of the pectoral fascia, with an occasional thick layer of the underlying muscle, together with the axillary nodes. The eminent surgeon Theodor Billroth (b. 1829) of Vienna also removed the entire breast but questioned the value of local excision of the tumor with a surrounding zone of normal tissue. For fixed tumors, Billroth’s resections included the pectoral fascia, along with a thick layer of the underlying muscle. His mortality rate of 15.7% with mastectomy alone and 21.3% when axillary dissection was also performed was praised as superior in the 19th century. Ernst Küster (b. 1839) of Berlin, Germany, recommended that the axillary fat be removed along with the axillary glands. Lothar Heidenhain (b. 1860), a pupil of Volkmann, recommended removal of the superficial portion of the pectoralis major muscle even if the tumor was freely mobile, but he also recommended that the entire muscle, with its underlying connective tissue, be removed if the tumor was fixed. Concerning benign breast disease, Sir Astley Cooper (b. 1768) ( Fig. 1.13 ), an eminent English surgeon, published Illustrations of the Diseases of the Breast in 1829, which clearly differentiated fibroadenomas from chronic cystic mastitis.

Other important milestones of the 19th century are as follows. In 1829 French gynecologist and obstetrician Joseph Récamier introduced the term metastasis to describe the spread of cancer. In 1830 the English surgeon Everard Home (b. 1756) published a book on cancer that contained the first illustrations of the appearance of cancer cells under the microscope. Heinrich von Waldeyer-Hartz (b. 1836) cataloged a histologic classification of cancers showing that carcinomas come from epithelial cells, whereas sarcomas come from mesodermal tissue. In 1865 Victor Cornil (b. 1837) described malignant transformation of the acinar epithelium of the breast. In 1893 the first description of loss of differentiation by cancer cells (“anaplasia”) was made by David von Hansemann, a German pathologist.

American Surgery

In the 19th century, Philadelphia was the medical center of the United States. It harbored the country’s oldest medical college, the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765), the Jefferson Medical College (founded in 1824), and more than 50 other medical schools. It had a permanent medical college for women, as well as one in homeopathy and one in osteopathy.

Joseph Pancoast (b. 1805) was a dexterous surgeon-anatomist, who in the flowery language of his era, was said “to have an eye as quick as a flashing sunbeam and a hand as light as floating perfume.” His Treatise on Operative Surgery, published in 1844 in the preanesthetic and preantiseptic era, illustrates a mastectomy ( Fig. 1.14 ). The patient is awake, with eyes open, and is semireclining. An assistant compresses the subclavian artery above the clavicle with the thumb of one hand. Larger vessels in the wound are compressed with the thumb and index finger of the assistant’s other hand. Ligatures are left long and brought through the lower pole of the wound, where they act as a drain and can be pulled out later as they slough off. In one of the smaller sketches, the axillary glands are shown in continuity with the breast, visualized through a single incision that extended into the axilla. This was the first illustration of en bloc removal of the breast with its axillary lymphatic drainage. Skin removal was scanty, with easy approximation of the wound using five wide adhesive strips.

Samuel David Gross (b. 1805) ( Fig. 1.15 ) was designated as “the greatest American surgeon of his time.” His approach to cancer of the breast, however, was more conservative than that of Pancoast, his colleague. He described extirpation of the breast as “generally a very easy and simple affair.” Using a small elliptical incision, he attempted to save enough skin for easy approximation of the edges of the wound. He aimed for healing by first intention, which was less likely if the wound were permitted to gape. In dealing with inordinately vascular tumors, he ligated each vessel but generally considered this as awkward and unnecessary. Glands in the axilla were removed only if grossly involved, in which case they were removed through the outer angle of the incision or through a separate one. The glands were enucleated with the finger or handle of the scalpel. It was his rule not to approximate the skin until 4 or 5 hours after the operation, “lest secondary hemorrhage should occur, and thus necessitate the removal of the dressings.” In the sixth edition of his System of Surgery (1882), he devoted 30 pages to diseases of the breast.

Samuel W. Gross (b. 1837) took a much more aggressive approach than that of his eminent father. He stated in 1887 that “no matter what the situation of the tumor may be, or whether glands can or cannot be detected in the armpit, the entire breast, with all the skin covering it, the paramammary fat, and the fascia of the pectoral muscle are cleanly dissected away, and the axillary contents are extirpated. It need scarcely be added that aseptic precautions are strictly observed.” Removal of all the skin of the breast led to its designation as the “dinner plate operation.” Against the criticism that an open large wound resulted in granulations from which cancer would again develop, he said, “When fireplugs produce whales, and oak trees polar bears, then will granulations produce cancer, and not until then.”

The younger Gross personally examined all the tumors he removed under the microscope. In 1879 he helped his father found the Philadelphia Academy of Surgery, the oldest surgical society in the United States. After his premature death in 1889, his widow married William Osler. In her will of 1928, Lady Osler bequeathed an endowment for a lectureship at the Jefferson Medical College in honor of her first husband and his special interest in tumors.

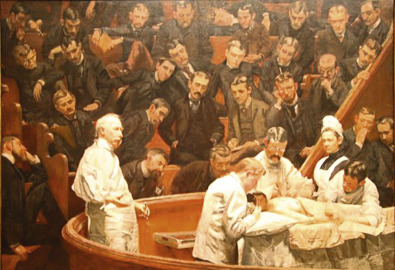

D. Hayes Agnew (b. 1818) of the University of Pennsylvania wrote Principles and Practice of Surgery (1878), which endorsed Listerian antisepsis. He shared the pessimistic view of many eminent surgeons of the time that few cancers were ever cured with surgery. The Agnew Clinic by Thomas Eakins (b. 1844) is the masterpiece of American art depicting a mastectomy performed in 1889 under conditions that would have been considered ideal for the time ( Fig. 1.16 )