Histologic Variants of Urothelial Carcinoma

With increasing experience with urothelial carcinomas at the light microscopic level, the spectrum of microscopic forms of urothelial carcinoma has been expanded to include several unusual histologic variants, which have been incorporated in the new WHO classification (1). The term variant is used to describe a distinctively different histomorphologic phenotype of a certain type of neoplasm (2, 3, 4, 5). By definition, they arise from the surface urothelium. The recognition of histologic variants is important because (a) some types may be associated with a different clinical outcome, and some of them have been incorporated into risk stratification models (6, 7); (b) some may have a different therapeutic approach (8, 9, 10); or (c) awareness of the unusual pattern may be critical in avoiding diagnostic misinterpretations. We generally recommend following two general rules when dealing with histologic variants. First, the variant histology should be documented in the pathology reports because metastatic tumors usually continue to exhibit the distinctive histologic pattern, and knowledge of the variant histology facilitates association of the metastasis to the primary tumor. Second, because the pattern of the neoplasm deviates from the conventional form, the possibility that this “unusual” morphology represents a metastasis should be considered and ruled out.

DECEPTIVELY BENIGN VARIANTS OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

Some urothelial carcinomas have histologic variants that mimic nonneoplastic conditions such as cystitis cystica, proliferative von Brunn nests, nephrogenic adenoma, and inverted papilloma (11, 12, 13, 14). Awareness of these variants (nested [small and large nested], urothelial carcinoma with small tubules, microcystic urothelial carcinoma, and inverted papilloma-like growth pattern) is important because limited sampling, particularly in cystoscopic biopsy specimens, could lead to an underdiagnosis of malignancy (11, 12, 13, 14).

Nested Variant of Urothelial Carcinoma

From a pathologist’s perspective, the nested variant should appropriately be recognized as a malignant process, particularly in superficial biopsies.

This variant, characterized by a nested, deceptively bland pattern, may be composed of small nests or, as recently described, large nests (“large nested variant of urothelial carcinoma”).

This variant, characterized by a nested, deceptively bland pattern, may be composed of small nests or, as recently described, large nests (“large nested variant of urothelial carcinoma”).

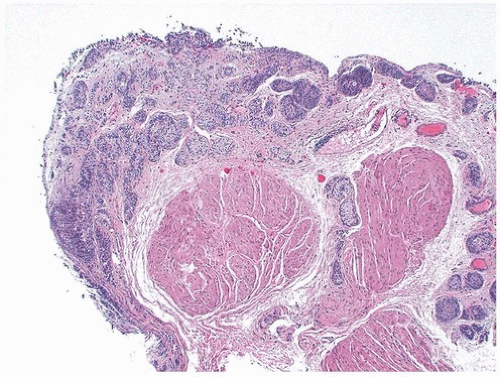

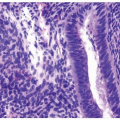

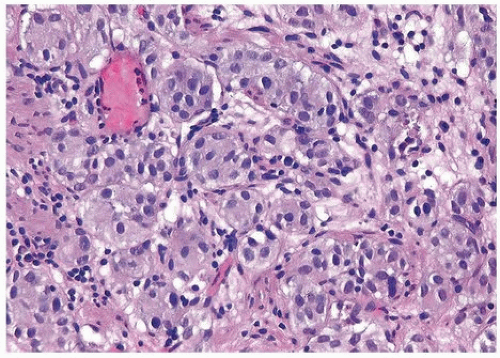

The nested pattern (referring to carcinomas with small nested pattern) has distinct patterns in the superficial and deep portions. In superficial biopsy samples and transurethral resectates, the superficial component appears as discrete nests, occasionally with tubules or even microcysts (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17) (Figs. 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.7, 6.8, 6.9) (efigs 6.1-6.18). The nests are tightly packed, often confluent, and haphazardly arranged with little or no intervening stroma. Most nests have a relatively bland cytologic appearance, but at least some

have more atypical nuclei and larger nucleoli. Overlying papillary carcinoma or recognizable flat in situ disease is usually not evident (18); a variable component of conventional urothelial carcinoma may be present (19). The architectural complexity, confluence, and anastomosis between the nests are features that are particularly helpful in distinguishing carcinoma from von Brunn nests or other benign conditions. Proliferative von Brunn nests extend to a uniform level within the lamina propria creating a sharp, linear border at the base that contrasts with the irregular, infiltrative base of nested carcinoma. In the ureter and renal pelvis, von Brunn nests tend to be smaller and more crowded than in the bladder, closely mimicking nested carcinoma (Figs. 1.17, 1.18). However, von Brunn nests in these sites still have a lobular or linear arrangement with a sharp border at the base. Also, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is exceedingly rare in the ureter and renal pelvis, and a diagnosis of nested carcinoma at these sites should be made with great caution on biopsy and only in the presence of a cystoscopic filling defect or an obstructive mass lesion.

have more atypical nuclei and larger nucleoli. Overlying papillary carcinoma or recognizable flat in situ disease is usually not evident (18); a variable component of conventional urothelial carcinoma may be present (19). The architectural complexity, confluence, and anastomosis between the nests are features that are particularly helpful in distinguishing carcinoma from von Brunn nests or other benign conditions. Proliferative von Brunn nests extend to a uniform level within the lamina propria creating a sharp, linear border at the base that contrasts with the irregular, infiltrative base of nested carcinoma. In the ureter and renal pelvis, von Brunn nests tend to be smaller and more crowded than in the bladder, closely mimicking nested carcinoma (Figs. 1.17, 1.18). However, von Brunn nests in these sites still have a lobular or linear arrangement with a sharp border at the base. Also, nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is exceedingly rare in the ureter and renal pelvis, and a diagnosis of nested carcinoma at these sites should be made with great caution on biopsy and only in the presence of a cystoscopic filling defect or an obstructive mass lesion.

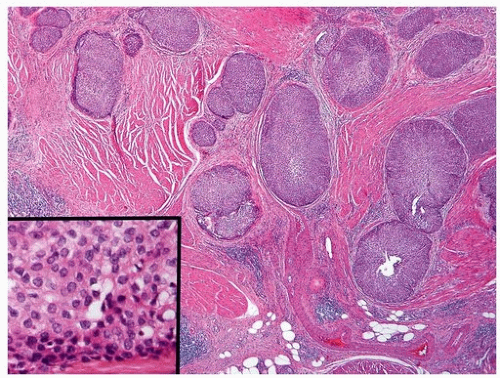

FIGURE 6.2 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. The nests are too small and crowded to represent von Brunn nests. Inset shows bland cytology. |

FIGURE 6.3 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. The nests are too small and crowded with complex architecture to represent von Brunn nests. |

FIGURE 6.4 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma (higher magnification of Fig. 6.3). |

FIGURE 6.5 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with focal tubule formation (higher magnification of Fig. 6.3). |

FIGURE 6.7 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Tumor invades muscularis propria (higher magnification of Fig. 6.6). |

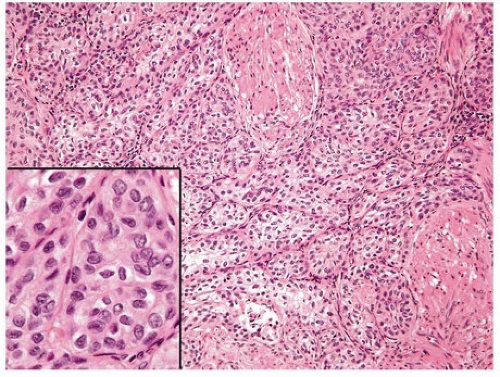

FIGURE 6.8 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with extension of nests into muscularis propria. Inset shows bland cytology. |

FIGURE 6.9 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with crowded almost back-toback proliferation of small nests (higher magnification [right]). |

In the deeper portion of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma, the neoplasm usually shows greater cytologic atypia and an irregular infiltrative pattern. These tumors are frequently muscle invasive and, despite their innocuous histology, are paradoxically associated with aggressive clinical outcome including metastasis and death. Even with therapy, 70% of patients with adequate follow-up died within 4 to 40 months of diagnosis (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). Nested carcinomas tend to present as locally advanced tumors, however, stage for stage their prognosis is similar to urothelial tumors of similar stage (19). For this reason, we believe that a bladder cancer with only pure to predominant histology where the deceptively bland histology raised other differential diagnostic considerations should be reported as nested carcinoma.

If there is a conspicuous and obvious component of high-grade invasive urothelial carcinoma, we do not believe that the diagnosis of nested carcinoma should be made. Invasion of the muscularis propria, despite the bland nuclear features, is diagnostic of carcinoma and is the most definitive distinguishing feature. Unfortunately, in some superficial biopsies or those complicated by extensive cautery artifact, it may be difficult to categorize lesions as unequivocally benign or malignant. In such cases, it is important to correlate the microscopic findings with the clinical impression of the urologist, as the presence of a mass lesion would indicate the need for additional sampling to ascertain for the presence of a more aggressive lesion.

If there is a conspicuous and obvious component of high-grade invasive urothelial carcinoma, we do not believe that the diagnosis of nested carcinoma should be made. Invasion of the muscularis propria, despite the bland nuclear features, is diagnostic of carcinoma and is the most definitive distinguishing feature. Unfortunately, in some superficial biopsies or those complicated by extensive cautery artifact, it may be difficult to categorize lesions as unequivocally benign or malignant. In such cases, it is important to correlate the microscopic findings with the clinical impression of the urologist, as the presence of a mass lesion would indicate the need for additional sampling to ascertain for the presence of a more aggressive lesion.

Another differential diagnostic consideration is nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia) with a more solid appearance (12). The problem is compounded when the nephrogenic adenoma has an “infiltrative” growth at the base. The marked variation or occasional large nests, nuclear atypia in deeper aspects, stromal reaction, and muscularis propria invasion argue for a nested carcinoma diagnosis. Nephrogenic adenoma may show other coexisting patterns (tubules, papillary, signet ring, cystic) and often contains stroma that is edematous and inflamed. Several other tumors primarily or secondarily involving the urinary bladder may have a nested pattern including paraganglioma, carcinoid tumor, prostatic adenocarcinoma, melanoma, and alveolar soft part sarcoma (20). In this differential diagnostic context, once the diagnosis of neoplasia is made, the issue is the distinction of urothelial versus nonurothelial nature of the different nested tumors and their distinction from one another by using an appropriately constructed immunohistochemical panel. Immunohistochemical studies indicate that the nested variant shares many characteristics with invasive urothelial carcinoma including positivity for GATA3, S100P, uroplakin 2, and cytokeratins 7 and 20 and for p63 and high molecular weight cytokeratin (HMWCK) (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26). The nested variant shows loss or absence of immunoreactivity for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27 and positivity for tumor suppressor gene p53, which have been associated with poor prognosis in conventional urothelial carcinoma, although these tests are not in routine clinical use (22). There have been studies supporting MIB-1 as a useful marker in the distinction from benign proliferative lesions, although it must be noted that some cases of nested variant may have low MIB-1 proliferation index and some proliferative lesions may have higher rates (22, 27). This variability and range of immunostaining for MIB-1 has precluded us from using p53 or MIB-1 immunohistochemistry as a diagnostic adjunct for such cases. FISH studies in paraffin-embedded tissues may be helpful to distinguish nested carcinoma from von Brunn nests (28), although this testing is not readily available.

Large Nested Variant of Urothelial Carcinoma

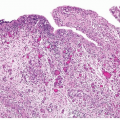

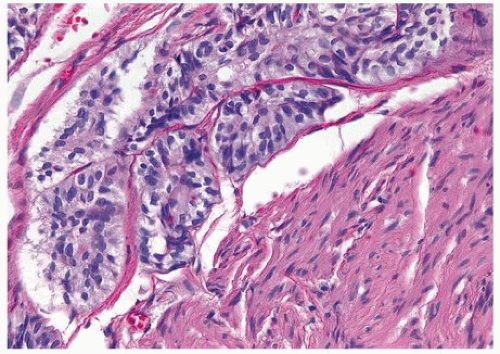

Urothelial carcinomas may occasionally present with a large nested morphology that may simulate an inverted urothelial tumor or when present in fragmented transurethral resection fragments pose considerable challenges in

terms of recognition of invasion. The tumors are composed of broad nests of tumor with bland cytologic features that are randomly and haphazardly arranged and are present deep in the bladder wall, including between muscle bundles of muscularis propria (Fig. 6.10). Upon closer inspection, a slightly greater degree of nuclear atypia is invariably present (helpful if the differential is with von Brunn nests with atypia). While evaluating for invasion versus inverted or verrucous carcinoma-like growth, the presence of tumor between muscularis propria is virtually diagnostic of muscle-invasive carcinoma. Except for urachal rests and the intramural segment of the ureter, benign urothelial proliferations or lesions do not involve the muscularis propria. Desmoplasia, while unusual, may be present in large nested urothelial carcinomas and is of further value in confirming invasion when present. In contrast to the small nested pattern, a surface urothelial component may be recognized in some of these cases. Follow-up data in the limited published series show disease persistence and progression suggesting that the low-grade appearance is deceptive in terms of outcome (29).

terms of recognition of invasion. The tumors are composed of broad nests of tumor with bland cytologic features that are randomly and haphazardly arranged and are present deep in the bladder wall, including between muscle bundles of muscularis propria (Fig. 6.10). Upon closer inspection, a slightly greater degree of nuclear atypia is invariably present (helpful if the differential is with von Brunn nests with atypia). While evaluating for invasion versus inverted or verrucous carcinoma-like growth, the presence of tumor between muscularis propria is virtually diagnostic of muscle-invasive carcinoma. Except for urachal rests and the intramural segment of the ureter, benign urothelial proliferations or lesions do not involve the muscularis propria. Desmoplasia, while unusual, may be present in large nested urothelial carcinomas and is of further value in confirming invasion when present. In contrast to the small nested pattern, a surface urothelial component may be recognized in some of these cases. Follow-up data in the limited published series show disease persistence and progression suggesting that the low-grade appearance is deceptive in terms of outcome (29).

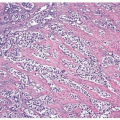

Urothelial Carcinoma with Small Tubules

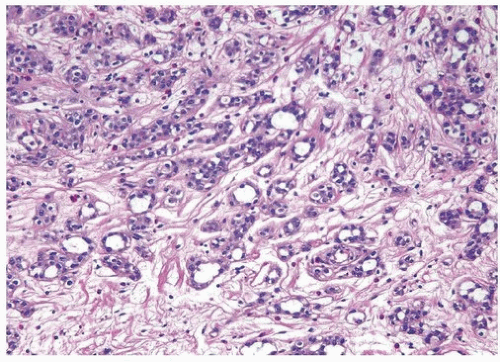

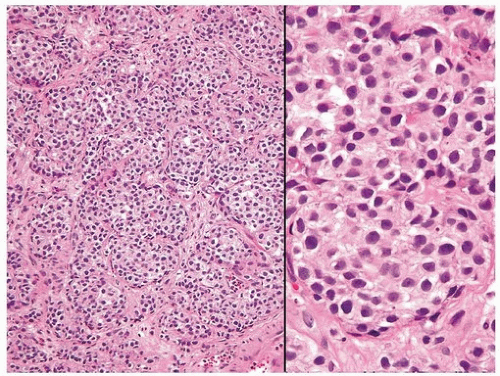

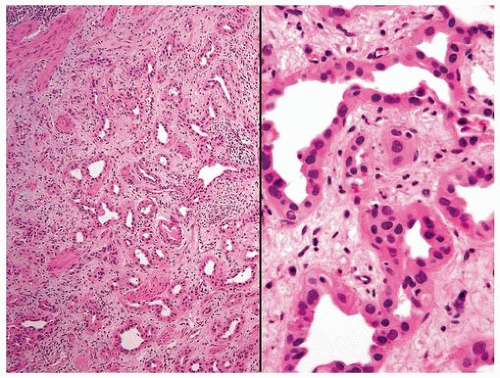

Some urothelial carcinomas may have a prominent component of smallsized to medium-sized, round to elongated tubules that may be misdiagnosed as nephrogenic adenoma (metaplasia) or cystitis glandularis (14, 30) (Figs. 6.11, 6.12, 6.13, 6.14, 6.15, 6.16). The tubules, however, are lined by urothelial cells in contrast to the cuboidal, columnar, or occasionally flattened cells that line the tubules of nephrogenic adenoma. The small caliber of tubules and random infiltrative pattern contrast with the overall organized arrangement of

cystitis cystica or glandularis. Transition to areas of nested variant is common. The cytologic features are invariably low grade, but the recognition of carcinoma is based on diffusely infiltrative architecture, considerable variation of tubular shape with haphazard organization, and the frequent presence of muscle invasion. The biologic significance of this pattern is uncertain, but some of these cases occur in conjunction with the nested pattern and may result in an aggressive behavior. The differential diagnosis with an extension of a prostatic carcinoma is often also a consideration but easily handled by immunohistochemistry for prostate-specific and urothelial markers (31). Like the nested variant, the chief reason for awareness

of this morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma is not to mistake it in superficial biopsies as a benign glandular proliferative lesion (5, 11, 16, 17, 21, 22, 32).

cystitis cystica or glandularis. Transition to areas of nested variant is common. The cytologic features are invariably low grade, but the recognition of carcinoma is based on diffusely infiltrative architecture, considerable variation of tubular shape with haphazard organization, and the frequent presence of muscle invasion. The biologic significance of this pattern is uncertain, but some of these cases occur in conjunction with the nested pattern and may result in an aggressive behavior. The differential diagnosis with an extension of a prostatic carcinoma is often also a consideration but easily handled by immunohistochemistry for prostate-specific and urothelial markers (31). Like the nested variant, the chief reason for awareness

of this morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma is not to mistake it in superficial biopsies as a benign glandular proliferative lesion (5, 11, 16, 17, 21, 22, 32).

FIGURE 6.11 Tubular variant of urothelial carcinoma invading muscularis propria (higher magnification [right]). |

FIGURE 6.13 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with tubule formation. Note irregular proliferation of nests and tubules in inflamed, edematous stroma. |

FIGURE 6.14 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with moderate atypia (higher magnification of Fig. 6.13). Although the cytologic features appear “low grade” on low power, this high-power illustration shows diagnostic features of malignancy. |

FIGURE 6.15 Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with tubule formation (higher magnification of Fig. 6.13). |

Microcystic Urothelial Carcinoma

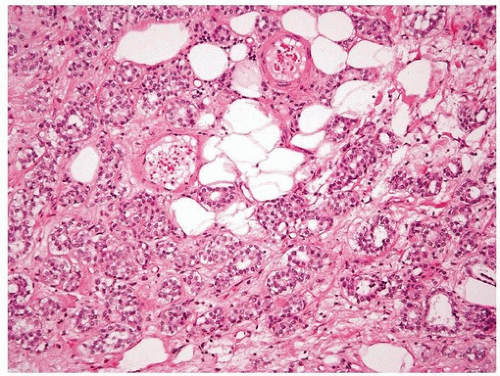

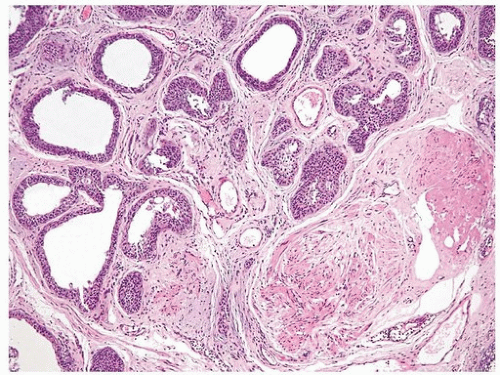

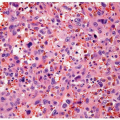

This is yet another deceptively benign form of urothelial carcinoma and is exemplified by the formation of numerous microcysts, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of cystitis cystica upon superficial examination or in limited biopsy specimens (33, 34, 35) (Figs. 6.17, 6.18). The pattern is

characterized by prominent widespread cystic change of variable size within nests of urothelial carcinoma or within urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation. The cysts are round to oval and 1 to 2 mm in size and contain secretions that may be targetoid. The cyst lining is most commonly urothelial and is usually focally glandular; larger cysts may possess a flattened epithelium or a denuded lining. Cytologic blandness is present by definition, and the most critical feature in distinguishing this carcinoma type from benign conditions is the variation, often dramatic, in size and shape of the epithelial formations and the relatively haphazard infiltrative growth into the wall of the urinary bladder. There is no striking biologic

significance associated with this pattern, except that it represents a potentially serious diagnostic pitfall, particularly in limited samples (33, 35, 36). Once again, the nested, small tubule, and microcystic variants may coexist in the same lesion (14). The chief differential diagnostic considerations are from cystitis cystica et glandularis and von Brunn nests, which overall tend to have a very organized appearance and lack the overt size variation that typifies microcystic carcinoma (33, 34, 35, 37). Recent studies have reported positivity for GATA3, CK20, CK7, S100P, p63, and HMWCK in these tumors (25, 36).

characterized by prominent widespread cystic change of variable size within nests of urothelial carcinoma or within urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation. The cysts are round to oval and 1 to 2 mm in size and contain secretions that may be targetoid. The cyst lining is most commonly urothelial and is usually focally glandular; larger cysts may possess a flattened epithelium or a denuded lining. Cytologic blandness is present by definition, and the most critical feature in distinguishing this carcinoma type from benign conditions is the variation, often dramatic, in size and shape of the epithelial formations and the relatively haphazard infiltrative growth into the wall of the urinary bladder. There is no striking biologic

significance associated with this pattern, except that it represents a potentially serious diagnostic pitfall, particularly in limited samples (33, 35, 36). Once again, the nested, small tubule, and microcystic variants may coexist in the same lesion (14). The chief differential diagnostic considerations are from cystitis cystica et glandularis and von Brunn nests, which overall tend to have a very organized appearance and lack the overt size variation that typifies microcystic carcinoma (33, 34, 35, 37). Recent studies have reported positivity for GATA3, CK20, CK7, S100P, p63, and HMWCK in these tumors (25, 36).

FIGURE 6.18 Microcystic urothelial carcinoma (higher magnification of Fig. 6.17). |

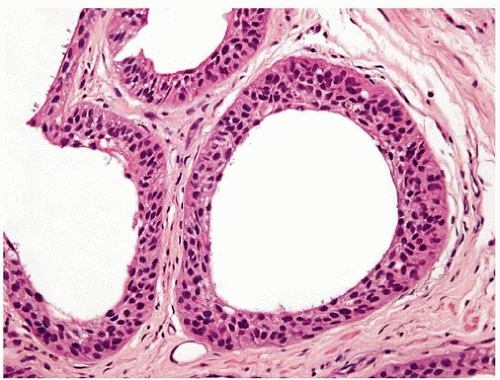

INVERTED PAPILLOMA-LIKE GROWTH PATTERN OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

This form of urothelial carcinoma is associated with two diagnostic concerns: (a) distinction from inverted papilloma (see Chapter 4) and (b) difficulty in assessing invasion (see Chapter 5) (38, 39). Distinction from the inverted papilloma requires attention to the architectural and cytologic features of the lesion. Urothelial carcinomas with inverted growth usually have thicker columns, with irregularity in width of the columns or transition of cords and columns into large rounded nests. The characteristic orderly maturation, spindling, and peripheral palisading seen in inverted papilloma are generally absent or inconspicuous in urothelial carcinomas with inverted growth. The amount of stroma between the epithelial columns and cords can be quite variable from area to area. Unequivocal stromal invasion into the lamina propria or muscularis propria rules out the diagnosis of inverted papilloma, as does the presence of appreciable exophytic papillary architecture. Furthermore, cytologic atypia is an important feature for the diagnosis of carcinoma; thus, carcinomas with inverted growth, like their exophytic counterparts, may be classified as low grade or high grade. Inverted urothelial carcinoma may or may not be associated with destructive invasion (see Chapter 5 for criteria for invasion). Although the distinction of inverted papilloma versus carcinoma is usually based on routine light microscopic evaluation, a study has investigated and proposed a role for ancillary techniques including immunohistochemistry (p53, Ki-67, CK20 all show statistically significant higher expression in carcinomas as compared to urothelial papillomas) and UroVysion FISH studies (chromosomal abnormalities absent in urothelial papilloma and present in urothelial carcinoma) (40). These tests are currently not recommended for clinical use until further studies validate the results.

MICROPAPILLARY VARIANT OF UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA

This histologic variant of urothelial carcinoma has a micropapillary architecture that is reminiscent of the papillary configuration seen in ovarian papillary serous tumors (41, 42, 43, 44, 45). This rare histologic variant comprises

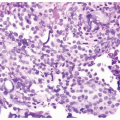

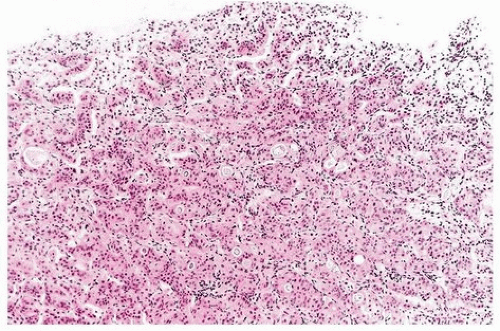

0.6% to 1% of urothelial carcinomas and shows a definite male predominance (male-to-female ratio 5:1) that is higher than in conventional urothelial carcinoma (3:1). More than 95% of these tumors are muscle invasive at the time of presentation. Histologically, the micropapillary component of these tumors may be encountered in (a) the noninvasive component, (b) the invasive component, and (c) metastasis. This pattern may be focal, extensive (greater than 90%), or exclusive. Urothelial carcinoma in situ (urothelial CIS) is demonstrable in greater than 50% of the cases, and concurrent glandular differentiation is known to occur. Six histologic features of the micropapillary component are noteworthy. First, micropapillary carcinoma has two distinct patterns: On the surface, it forms slender, delicate filiform processes, rarely with a fibrovascular core (Figs. 6.19, 6.20, 6.21, 6.22) (efigs 6.19-6.22). When cut in cross sections, these papillae appear as glomeruloid bodies, sometimes with reversed polarity or palisading of cells. When micropapillary features are only present in the noninvasive component, the tumor should not be called micropapillary carcinoma. Alternatively, they could be designated as either “CIS with micropapillary features” or “high-grade noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features.” When diagnosing these noninvasive variant morphologies in the absence of invasive carcinoma, we specifically add in the report: “There is no invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma” to clarify the diagnosis and to prevent overtreatment. In the invasive component and in all metastatic sites, the tumor cells are arranged in small tight nests or balls (Figs. 6.23, 6.24, 6.25, 6.26, 6.27, 6.28) (efigs 6.23-6.36); the absence of vascular cores allows for the recognition of micropapillae. Second, the presence of epithelial ring forms tumor cells resulting from intracytoplasmic vacuolation. Third, psammoma bodies, a feature of ovarian papillary

serous neoplasia, are exquisitely rare in micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. Fourth, the tumor cells in the invasive and metastatic components are aggregated in lacunae, which mimic vascular invasion. This feature is intriguing and extremely characteristic of invasive micropapillary carcinoma. The presence of multiple nests within the same lacunar space is very helpful to distinguish this pattern from retraction artifact around invasive carcinoma, which may be quite prominent in some usual or conventional urothelial carcinomas. The spaces may be lined focally by flattened spindled cells or may be devoid of any lining. In most instances, there is no host response to the tumor cells that merely seem to reside in hollow spaces at various random intervals within the tumor (44). This pattern of lacunae containing neoplastic cells is also seen in the metastatic sites. Awareness that lacunae of micropapillary urothelial carcinoma may mimic vascular

invasion is important so that one does not overdiagnose the presence of vascular invasion. Fifth, micropapillary carcinoma always demonstrates a high nuclear grade (high grade by WHO/ISUP classification), although some areas within a neoplasm may parallel low-grade urothelial carcinoma. Sixth, most reported cases with micropapillary carcinoma show at least focal unequivocal vascular invasion. Like urothelial carcinomas, the tumors are often positive for CK7, CK20, uroplakin 2, GATA3, S100P, p63, and HMWCK (25, 26, 46). Leu-M1, CEA, and Ca antigen 125 may be focally positive, in keeping with glandular differentiation that may be concurrent. While most micropapillary urothelial carcinomas are muscle invasive at presentation, a small subset of urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features may be only noninvasive (47) or invasive limited to the lamina propria (48). Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features may also be associated with urothelial CIS (conventional flat histology) or invasive micropapillary carcinoma (see Chapter 2).

0.6% to 1% of urothelial carcinomas and shows a definite male predominance (male-to-female ratio 5:1) that is higher than in conventional urothelial carcinoma (3:1). More than 95% of these tumors are muscle invasive at the time of presentation. Histologically, the micropapillary component of these tumors may be encountered in (a) the noninvasive component, (b) the invasive component, and (c) metastasis. This pattern may be focal, extensive (greater than 90%), or exclusive. Urothelial carcinoma in situ (urothelial CIS) is demonstrable in greater than 50% of the cases, and concurrent glandular differentiation is known to occur. Six histologic features of the micropapillary component are noteworthy. First, micropapillary carcinoma has two distinct patterns: On the surface, it forms slender, delicate filiform processes, rarely with a fibrovascular core (Figs. 6.19, 6.20, 6.21, 6.22) (efigs 6.19-6.22). When cut in cross sections, these papillae appear as glomeruloid bodies, sometimes with reversed polarity or palisading of cells. When micropapillary features are only present in the noninvasive component, the tumor should not be called micropapillary carcinoma. Alternatively, they could be designated as either “CIS with micropapillary features” or “high-grade noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features.” When diagnosing these noninvasive variant morphologies in the absence of invasive carcinoma, we specifically add in the report: “There is no invasive micropapillary urothelial carcinoma” to clarify the diagnosis and to prevent overtreatment. In the invasive component and in all metastatic sites, the tumor cells are arranged in small tight nests or balls (Figs. 6.23, 6.24, 6.25, 6.26, 6.27, 6.28) (efigs 6.23-6.36); the absence of vascular cores allows for the recognition of micropapillae. Second, the presence of epithelial ring forms tumor cells resulting from intracytoplasmic vacuolation. Third, psammoma bodies, a feature of ovarian papillary

serous neoplasia, are exquisitely rare in micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. Fourth, the tumor cells in the invasive and metastatic components are aggregated in lacunae, which mimic vascular invasion. This feature is intriguing and extremely characteristic of invasive micropapillary carcinoma. The presence of multiple nests within the same lacunar space is very helpful to distinguish this pattern from retraction artifact around invasive carcinoma, which may be quite prominent in some usual or conventional urothelial carcinomas. The spaces may be lined focally by flattened spindled cells or may be devoid of any lining. In most instances, there is no host response to the tumor cells that merely seem to reside in hollow spaces at various random intervals within the tumor (44). This pattern of lacunae containing neoplastic cells is also seen in the metastatic sites. Awareness that lacunae of micropapillary urothelial carcinoma may mimic vascular

invasion is important so that one does not overdiagnose the presence of vascular invasion. Fifth, micropapillary carcinoma always demonstrates a high nuclear grade (high grade by WHO/ISUP classification), although some areas within a neoplasm may parallel low-grade urothelial carcinoma. Sixth, most reported cases with micropapillary carcinoma show at least focal unequivocal vascular invasion. Like urothelial carcinomas, the tumors are often positive for CK7, CK20, uroplakin 2, GATA3, S100P, p63, and HMWCK (25, 26, 46). Leu-M1, CEA, and Ca antigen 125 may be focally positive, in keeping with glandular differentiation that may be concurrent. While most micropapillary urothelial carcinomas are muscle invasive at presentation, a small subset of urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features may be only noninvasive (47) or invasive limited to the lamina propria (48). Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with micropapillary features may also be associated with urothelial CIS (conventional flat histology) or invasive micropapillary carcinoma (see Chapter 2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree