(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

Hip disarticulation is performed for proximal malignant tumors of the lower extremity with extensive involvement of the underlying femur in addition to the soft tissues, so that they are not amenable to a lesser procedure. It is performed for tumors more distal than those requiring a hemipelvectomy and more proximal than those that can be treated with a high thigh amputation. Rather than hip disarticulation, some surgeons prefer to do a conservative hemipelvectomy, preserving the entire iliac crest. The conservative hemipelvectomy is done faster (as one has to go through less musculature) and provides greater margins. The functional difference between a conservative hemipelvectomy and hip disarticulation is small, although the hip disarticulation does allow easier fitting with a prosthesis. Tumors that are located in the mid thigh with extensive involvement of the soft tissues and the underlying femur may be treated with hip disarticulation, as may tumors proximal to this level but well below the level of the inguinal ligament (Fig. 53.1).

Fig. 53.1

This extensive tumor of the thigh also involving the femur may be treated with a hip disarticulation

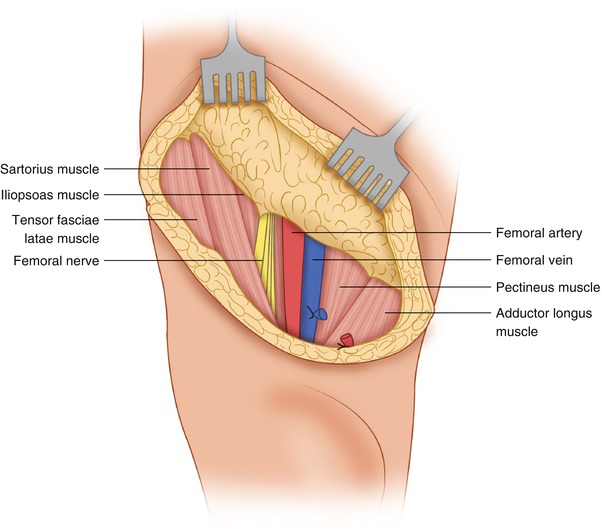

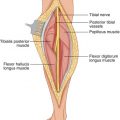

Anteriorly, the incision is carried out obliquely, along and below the level of the inguinal ligament through Scarpa’s fascia, exposing the sartorius muscle, femoral nerve, femoral vessels, pectineus muscle, and adductor longus (Fig. 53.2). When there is a possibility of lymph node metastasis, it is best to develop a flap anteriorly superficial to the inguinal nodes to above the inguinal ligament and then mobilize the inguinal lymph nodes off the femoral vessels, leaving them attached to the nodal chain inferiorly, to be removed en bloc with the specimen. The sartorius muscle is divided and the common femoral vessels are dissected, doubly ligated, and divided, while the femoral nerve is simply ligated and divided (Fig. 53.3). Lateral to the femoral vessels, the iliopsoas, the tensor fascia lata, and the straight and reflected heads of the rectus femoris are divided, thus exposing the hip joint (Fig. 53.4). The fascia lata is incised laterally and posteriorly at a level well below the inferior margin of the gluteus maximus and the muscular insertion of this muscle to the gluteal tuberosity, which is divided. Also divided are the insertions of the gluteus medius and minimus, piriformis, obturator internus and gemelli, and the obturator externus to the greater trochanter, exposing widely the hip joint. Dividing the iliofemoral ligament and the capsule of the joint allows wide exposure of the head and neck of the femur (Fig. 53.5). Medially, the adductors are divided. The pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, gracilis, and medial origin of the adductor magnus are divided close to their origin from the pubic bone. The obturator nerve and vessels (i.e., the nerve’s anterior and posterior divisions, found anterior and posterior to the adductor brevis) are ligated and divided (Fig. 53.6). The posterior part of the incision is carried well below the gluteal crease to the junction of the upper and middle thigh, so that one can be sure that the posterior flap will reach anteriorly to join the anterior part of the incision without tension after the specimen is removed. This is essentially a fishmouth incision with a short anterior fasciocutaneous flap and a long posterior myocutaneous flap. The sciatic nerve is found between the greater trochanter and the ischial tuberosity (Fig. 53.7). It is traced superiorly and is ligated and divided at a higher point (Fig. 53.8). Of course the lower extremity has been prepped and draped so that it can be manipulated freely in flexing the thigh at the hip joint as needed. Also, flexion of the knee allows the dissection and development of the posterior flap, which should include (in addition to the skin) subcutaneous tissue and fascia, with the gluteus maximus attached to its deep surface, making certain that the flap’s blood supply will be sufficient. Indeed, the blood supply of the posterior flap is guaranteed by leaving the gluteus maximus attached to the flap. The insertions of the piriformis, gemelli, the obturator internus and externus, and quadratus femoris to the greater trochanter are divided, if not done already. The origins of the semitendinosus, the long head of the biceps, and the semimembranosus are divided off the ischial tuberosity, and the origin of the adductor magnus along the ischial ramus is also divided (Fig. 53.8). The extremity is retracted. The ligamentum capitis femoris connecting the head of the femur to the acetabulum is divided, and the extremity is removed (Fig. 53.9). Following hemostasis and irrigation, a suction drain is placed. The posterior flap is sutured anteriorly, approximating the fascia lata to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 53.10). The weight-bearing area after this type of reconstruction is a sturdy posterior flap. Patients can more often be fitted with an effective prosthesis after hip disarticulation than after hemipelvectomy.