(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

The term “hemipelvectomy” implies the removal of the right or left hemipelvis along with the ipsilateral extremity and suggests that the division of the bone was carried through the sacroiliac joint. When part of the posterior portion of the iliac bone is preserved, the procedure is called “conservative hemipelvectomy.” A conservative hemipelvectomy suffices for most tumors requiring this amputation. Although hemipelvectomy has been performed rarely for benign conditions extensively involving the soft tissues and underlying bones at the level of the hip, it is usually performed for malignant tumors located in the proximal thigh near the level of the inguinal ligament or in the iliac fossa, or tumors infiltrating the wall of the lesser pelvis that are so extensive in terms of soft tissue and osseous involvement that they cannot be conservatively removed completely with preservation of the extremity. The abdominoinguinal incision has made hemipelvectomy unnecessary for most tumors located in the iliac fossa or in the wall of the lesser pelvis. Tumors located in the buttock that are not resectable with a more conservative operation can be managed with this procedure, but an anterior flap is required. The unqualified term “hemipelvectomy” implies the use of a posterior flap.

The incision starts at the lower midline just above the pubic symphysis and then is extended transversely above the pubic crest to the level of the pubic tubercle and then obliquely in a lateral direction along the course of the inguinal canal (Fig. 54.1). The incision is carried to the iliac crest and then along the iliac crest posteriorly as far as is thought necessary to expose and resect the underlying tumor. Often it is extended posteriorly to the posterior superior iliac spine or the posterior inferior iliac spine. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised from the external inguinal ring in a lateral direction to the iliac crest and then along the crest posteriorly. The spermatic cord is exposed in the inguinal canal and surrounded by a tape. The posterior inguinal floor, consisting of the transversalis fascia, is incised (Fig. 54.2). The anterior rectus sheath on the ipsilateral side is incised just above the pubic crest, and then the rectus abdominis muscle is divided close to the pubic crest. The dissection continues to the incision already made in the posterior inguinal floor. The inferior epigastric vessels are ligated and divided medial to the internal inguinal ring, so the spermatic cord can be freed and displaced medially (provided, of course, that this part of the spermatic cord is not involved by tumor). Deep to the internal inguinal ring, which is opened, the spermatic cord shows the separation of its elements, the ductus deferens proceeding in a medial direction toward the spermatic vesicles and the internal spermatic vessels proceeding in a nearly vertical cephalad direction. The internal spermatic vessels usually must be ligated at this level, but if the testis has not been mobilized off its scrotal bed, this ligation does not cause necrosis of the testis, and its removal is not required. Lateral to the internal ring, the external oblique aponeurosis, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis are divided a short distance from, and along the lateral portion of, the inguinal ligament and then beside and medial to the iliac crest. The retroperitoneal space is thus opened up and the peritoneum is displaced superiorly, exposing the common iliac and external iliac vessels, as well as the internal iliac vessels and the ureter (Fig. 54.3). At this point, it is decided, depending on the location of the tumor, whether to ligate and divide the external iliac vessels or the common iliac vessels. The iliac vessels at either level are sufficiently mobilized to be ligated proximally and distally with a stout ligature of 0 silk and then are divided between vascular clamps. The free stump of the vessel proximally is sutured with a running 4-0 Prolene suture or a simple suture ligature to guard against the possibility of slippage of the proximal tie. The iliopsoas muscle is divided at the appropriate level above the cephalad extent of the tumor, and the femoral nerve, found between the psoas and the iliacus muscle, is ligated and divided (Fig. 54.4). The division of the iliacus muscle is continued laterally all the way to the iliac crest. Using a periosteal levator, the underlying bone at this level is exposed from the iliac crest to the greater sciatic notch (Fig. 54.5).

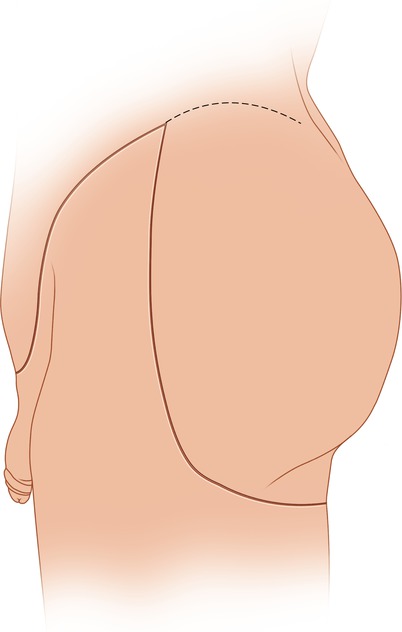

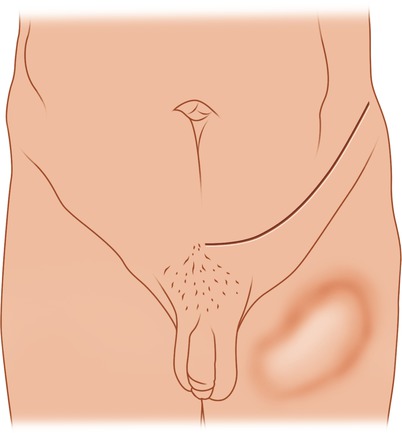

Fig. 54.1

The anterior portion of the incision for posterior flap hemipelvectomy is shown

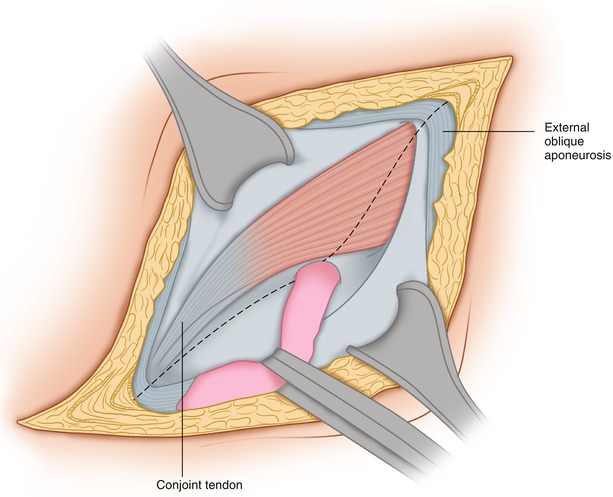

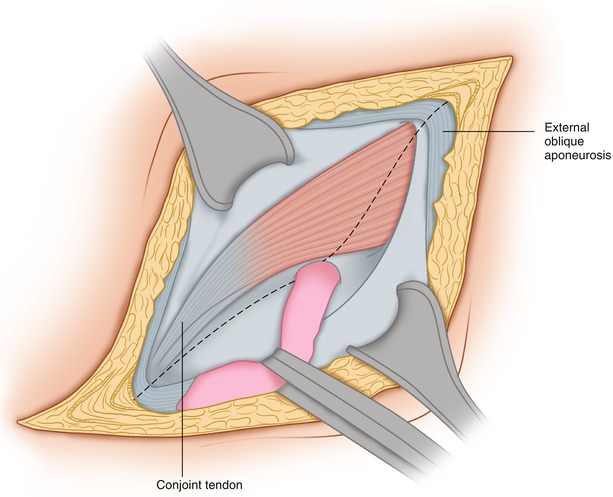

Fig. 54.2

The external oblique aponeurosis has been divided through the extent of the inguinal canal. The spermatic cord is retracted and the posterior inguinal wall (transversalis fascia) is about to be divided

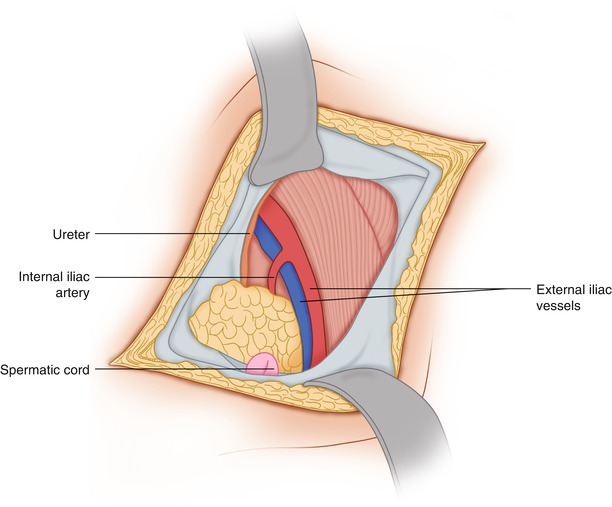

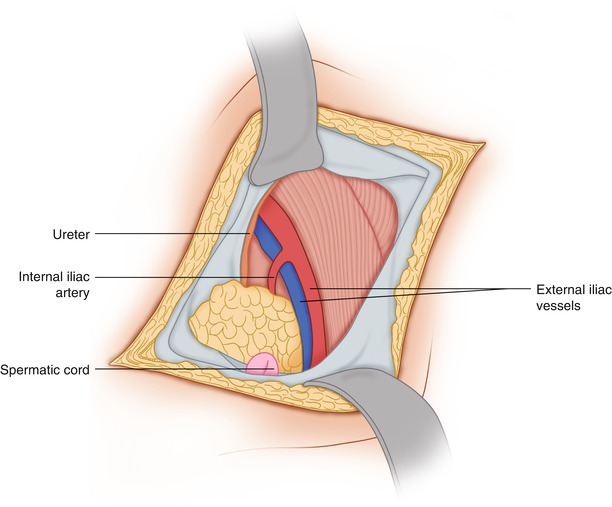

Fig. 54.3

The spermatic cord (ductus deferens) has been displaced medially. The internal spermatic vessels are divided above the internal ring. The iliac vessels, ureter, and iliopsoas muscle are exposed

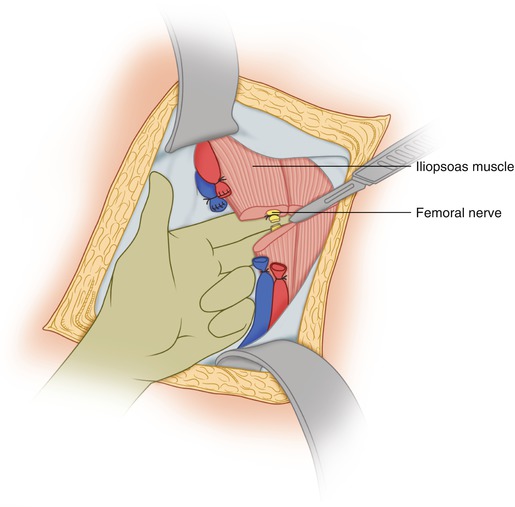

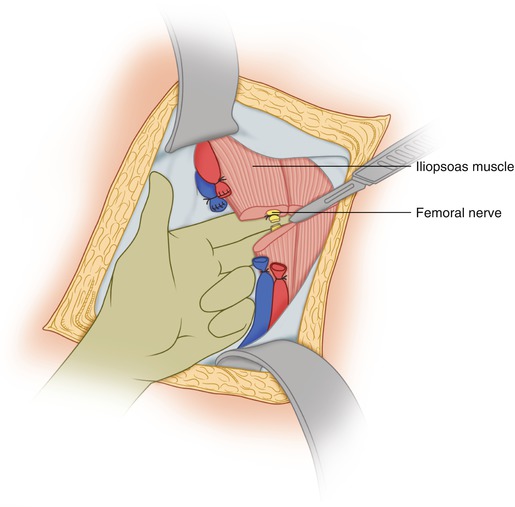

Fig. 54.4

In this patient, the external iliac vessels and the femoral nerve have been ligated and divided. The iliopsoas muscle is being divided

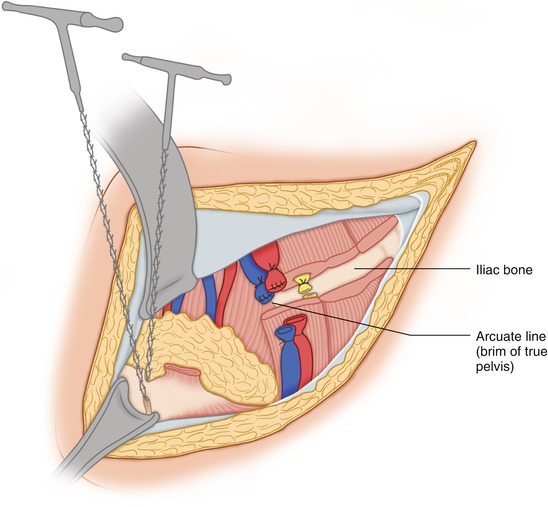

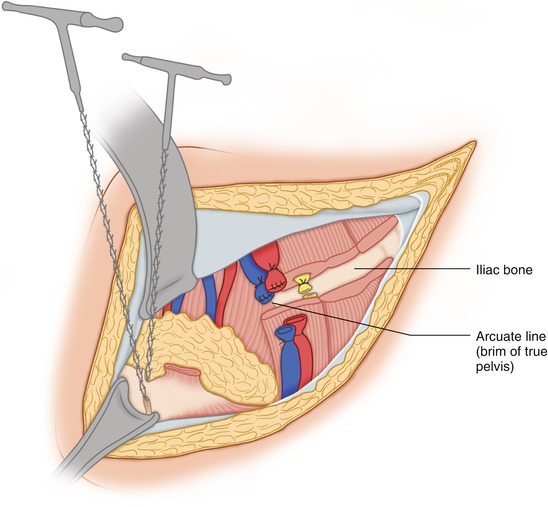

Fig. 54.5

The iliac bone is exposed. Division of the pubic symphysis with a Gigli saw is shown. This step of the procedure can be done more easily after the posterior incision has been performed and carried out to its union with the medial end of the anterior incision

The posterior flap is then outlined by starting from the posterior end of the anterior incision and proceeding in an inferior and posterolateral direction to the level of the greater trochanter and further below the gluteofemoral sulcus, to ensure that the posterior flap will be long enough to cover the defect following the hemipelvectomy (Fig. 54.6). This incision is deepened to the fascia. The insertion of the gluteus maximus to the iliotibial tract is divided, along with its muscular attachment to the gluteal tuberosity of the femur. Posteriorly and then medially, the incision is carried to the fascia, and it then continues anteriorly in the genitocrural crease then around the mons pubis to join the medial end of the anterior incision (Fig. 54.7). The sciatic nerve encountered between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter is traced to the greater sciatic notch, where it is proximally ligated and divided. The dissection continues along the ischiopubic ramus, dividing the origins of ischiocavernosus, transversus perinei superficialis, and transversus perinei profundus. Obviously, one should not dissect into the origin of the adductor or hamstring muscles because these structures and their osseous origins belong to the specimen. As the posterior flap is developed, the plane deep to the gluteus maximus is entered so that the gluteus maximus remains attached to the flap and provides its blood supply. Although the inferior gluteal vessels, along with the sciatic nerve, must be ligated and divided as one approaches the greater sciatic notch, the gluteus maximus retains blood supply from arterial branches entering its substance through its sacral origin. Thus if the entire iliac bone needs to be resected, the gluteus maximus can be detached off the small posterior origin from the iliac bone before dividing the sacroiliac joint proximally. When part of the posterior portion of the iliac bone can be preserved, the gluteus medius and minimus are divided along the desired line in correspondence with the exposure of the medial side of the iliac bone in the iliac fossa (Fig. 54.8). Therefore, these muscles are divided from the greater sciatic notch all the way to the iliac crest. With finger dissection around the greater sciatic notch, a right angle clamp clinging to the bone is passed, and then a Gigli saw is used around the notch, carefully avoiding any blood vessels by staying on the surface of the bone. A Gigli saw serves well to divide the iliac bone at that level (Fig. 54.9).