Hematopoietic Neoplasms: Principles of Pathologic Diagnosis

Daniel A. Arber

The hematopoietic neoplasms consist of acute and chronic leukemias, Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, plasma cell tumors, and the rare histiocytic and dendritic neoplasms. Each of these disease categories is now recognized to represent various heterogeneous disease groups that include a large number of distinct biologic entities.1, 2 With the great advances in targeted therapies and molecular genetic discoveries in the area of hematopoietic tumors, the number of distinct entities will continue to grow. Although the diagnosis and classification of these tumors were originally based primarily on morphologic features, sometimes supplemented by cytochemical studies,3, 4, 5, 6, 7 the diagnosis of hematopoietic tumors now requires a complex battery of specialized tools that almost always include immunophenotyping and frequently require cytogenetic and molecular genetic studies. Despite these advances, morphologic evaluation remains the cornerstone for the pathologic diagnosis for most diseases. Morphologic evaluation allows for cost-effective tissue processing and triaging for appropriate ancillary tests, which becomes increasingly important as the number of molecular genetic tests grows in this area.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Special considerations are often needed prior to sampling of tissue that is suspected to contain a hematopoietic neoplasm.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 The testing that will be needed depends on the clinical differential diagnosis as well as the initial pathologic impression of the sample. However, if the correct specimen types for ancillary tests are not saved prior to the initial pathologic review, the tissue may not be sufficient for these additional tests. Therefore, the hematologist, pathologist, or surgeon performing the procedure should have a clear understanding of the specimen requirements for the various tests that might be needed to rule in or out all suspected diseases. This often requires direct communication with the surgical pathologist or hematopathologist who will ultimately receive the sample prior to obtaining tissue. The submission of fresh tissue on saline-soaked gauze is ideal for tissue samples; however, this may not be feasible if the sample is taken at night or in a clinic that is physically separate from where the sample will be processed. Even in the latter setting, however, the sample may be sent by courier to a remote location quickly so that the tissue can be correctly triaged. In the absence of central processing of the sample, the physician performing the procedure must be aware of how to collect samples that are adequate for immunophenotyping studies, molecular and cytogenetic studies, and possible cultures. This problem is even more complicated when reference laboratories are used for different types of testing, an increasingly common practice, resulting in the need to split what may be very small samples prior to sending them out for these studies.

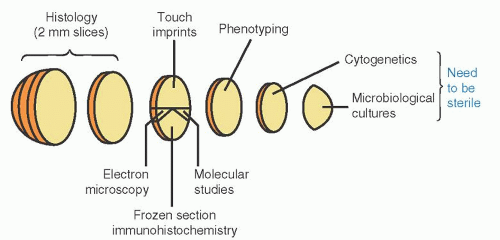

Ideally, the entire fresh sample is submitted to the pathology department within minutes of removal. There it may be received by a resident, technician, pathology assistant, or pathologist. No matter who receives the specimen, the clinical indication for the biopsy as well as any special clinical concerns or testing requirements needs to be clearly communicated. For tissues removed to rule out lymphoma, the specimens should be sampled in the fresh state. One protocol for lymph node sampling is provided in Figure 67.18 and is discussed in more detail below. Hematologists and pathologists should work together to establish a suitable protocol for their institution. Special needs should be communicated to the pathologist in advance of obtaining the sample, to ensure that the supporting testing areas, such as cytogenetics or microbiology, are prepared to receive the sample or to make arrangements to send samples quickly to the appropriate reference laboratory. It is worth noting that surgical pathologists receive lymph node specimens for a variety of indications, most of which do not require special processing and are simply formalin fixed. Without adequate clinical information and communication to alert them to a possibility of lymphoma or another hematopoietic tumor, tissue may not be sent for flow cytometry or cytogenetic studies, or saved for possible molecular genetic studies. Because the differential diagnosis of malignant lymphoma often includes infectious etiologies, the need for cultures or other infectious disease testing requiring fresh tissue or other special tissue preparation must also be communicated.

SPECIMEN PROCESSING

Triaging Protocols

How a sample for a suspected hematologic disorder is triaged often depends on the specimen type. Peripheral blood, bone marrow aspirate, and fine needle aspirate samples are often

triaged at the bedside by the physician collecting the sample. In this setting, the treating physician often orders flow cytometry immunophenotyping, cytogenetics, molecular genetics, and even cultures on samples collected in different tubes. Because the diagnosis of most disorders is still based in large part on morphologic features, it is advisable to use the initial bone marrow aspirate material for fresh smears, prepared at the bedside, or to make touch preparations for morphology in all cases with inadequate aspirate material (see Chapter 1). Subsequent aspirations may be more hemodiluted, but are usually still suitable for ancillary studies. In contrast, the triaging of tissue biopsy specimens is usually performed after the sample is submitted to the laboratory, as mentioned above and illustrated in Figure 67.1.8, 9 If lymphoma is suspected, sections of fresh material should be fixed for morphologic evaluation. If enough tissue is obtained, a portion of fresh tissue may also be sent for flow cytometry, and possibly for cytogenetics or cultures. Additional material may be frozen for future molecular genetic studies. In the rare instance where electron microscopy may be needed, a small portion of fresh tissue should be saved in glutaraldehyde. The exact tests performed, however, will depend on the clinical indication for the biopsy and communication between the pathologist and the treating hematologist.

triaged at the bedside by the physician collecting the sample. In this setting, the treating physician often orders flow cytometry immunophenotyping, cytogenetics, molecular genetics, and even cultures on samples collected in different tubes. Because the diagnosis of most disorders is still based in large part on morphologic features, it is advisable to use the initial bone marrow aspirate material for fresh smears, prepared at the bedside, or to make touch preparations for morphology in all cases with inadequate aspirate material (see Chapter 1). Subsequent aspirations may be more hemodiluted, but are usually still suitable for ancillary studies. In contrast, the triaging of tissue biopsy specimens is usually performed after the sample is submitted to the laboratory, as mentioned above and illustrated in Figure 67.1.8, 9 If lymphoma is suspected, sections of fresh material should be fixed for morphologic evaluation. If enough tissue is obtained, a portion of fresh tissue may also be sent for flow cytometry, and possibly for cytogenetics or cultures. Additional material may be frozen for future molecular genetic studies. In the rare instance where electron microscopy may be needed, a small portion of fresh tissue should be saved in glutaraldehyde. The exact tests performed, however, will depend on the clinical indication for the biopsy and communication between the pathologist and the treating hematologist.

Tissue Fixation and Processing

Proper specimen fixation and processing are essential for morphologic evaluation as well as for the optimal performance of ancillary studies.10, 11, 12 If lymphoma is suspected, thin sections of fresh material should be fixed for morphologic evaluation. In the past, special fixatives containing heavy metals such as mercuric chloride were used to improve cell morphology, but these fixatives are less commonly employed today due to difficulties in disposing of the mercury. Such fixatives also disrupt nucleic acids, making molecular studies often impossible. More routine formalin fixation will usually provide appropriate sections, as long as the tissue is fixed adequately, usually meaning overnight fixation of thin sections in fresh neutral buffered formalin. Formalin-fixed tissue is satisfactory for many DNA-based molecular assays, but some tests cannot be performed on fixed tissue. Tissue that is frozen should be stored at the lowest possible temperature (preferably -70°C to -80°C) and should not be stored in defrostable freezers.

Bone marrow aspirate specimens should be sent fresh after collection with minimal anticoagulant. Bone marrow biopsies should also be submitted fresh, or in fixative if delivery to the laboratory may be delayed. Again, heavy metal fixatives are less commonly available today and formalin or Bouin fixation is more frequently used. Bone marrow biopsies also must undergo decalcification, which may degrade some antigens and may reduce the ability to perform some assays. Decalcification in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid is considered the most gentle for antigen preservation,13 but some methods take several days to obtain adequate decalcification and this method is not routinely performed in most laboratories.

SAMPLING METHODS AND THEIR LIMITATIONS

Open Biopsy

The ideal specimen for pathologic evaluation is a large portion of tissue, received fresh and taken from an open biopsy. Such samples allow the maximum amount of tissue for morphologic analysis and ancillary studies. However, the increasing use of less-invasive procedures requires different approaches for different specimen types.

Peripheral Blood

Peripheral blood is often the easiest sample to obtain for an initial evaluation for a hematologic malignancy. Analysis of blood may allow for a diagnosis of leukemia or even peripheral blood involvement by lymphoma, although the absence of neoplastic cells in the blood cannot exclude disease elsewhere. Limitations to blood analysis include the inability to classify blast proliferations with <20% circulating blasts, and the lack of architecture needed for classification of some lymphomas involving blood. Despite these limitations, when the blood is involved by a hematopoietic tumor, morphologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular genetic studies of the blood may be of value in some patients. However, if a bone marrow is to be performed, duplication of testing on both the blood and marrow is usually unnecessary.

Bone Marrow Aspirate and Biopsy

Evaluation of marrow material will often provide much more information than peripheral blood alone in terms of classifying leukemic processes and determining the marrow blast percentage. In addition, some acute leukemias with monocytic features will have an increase in marrow blasts, but show maturation of neoplastic cells in the blood that may mimic chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; therefore, bone marrow assessment is essential in that setting. Both aspirate and biopsy materials provide critical information. Some diseases, such as lymphomas and metastatic tumors, may focally involve the marrow and are often associated with fibrosis, both factors that may make them undetectable on aspirate smears alone. When such focal disease processes are suspected, biopsies from more than one site will produce a higher yield for disease detection.14

Fine-Needle Aspirate and Core Biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration has become common as an evaluation tool for solid tumors and even lymphoma due to it being a relatively noninvasive procedure. The technique is ideal for the evaluation of relapse of disease but is now often used for initial patient evaluation. Although fine-needle aspiration coupled with flow cytometry immunophenotyping is ideal for the diagnosis of many low-grade lymphomas,15, 16 it has significant limitations due to the inability to determine architectural features of the lymphoma, to grade some lymphomas properly, and to identify focal disease or transformation. The addition of needle biopsies with or without aspiration and immunophenotyping overcomes some of these limitations, but a significant number of cases will need to go on to open biopsy for diagnosis and/or classification. Because of these limitations, excisional biopsy of easily accessible lymph nodes, when available, is preferred over lymph node aspiration or needle biopsy as an initial diagnostic procedure.

Laparoscopic Biopsy

Laparoscopic biopsies and other more invasive biopsy techniques often obtain more tissue than core biopsies, but often fragment

the specimen, especially with laparoscopic splenectomy specimens.17 Despite this, the fragments are usually large enough to determine the architectural pattern of the lymphoid infiltrate.

the specimen, especially with laparoscopic splenectomy specimens.17 Despite this, the fragments are usually large enough to determine the architectural pattern of the lymphoid infiltrate.

IMMUNOPHENOTYPING

Immunophenotyping is now essential in the diagnosis and classification of most hematopoietic tumors.2 It is necessary to distinguish precursor B- from precursor T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, to detect aberrant immunophenotypes in both lymphoid and myeloid leukemias, and to determine B-cell clonality and aberrancies in malignant lymphomas. Flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry are the primary methods currently used, and they have different advantages in the evaluation of these diseases.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree