INTRODUCTION

SUMMARY

The prevalence of HIV in the United States continues to rise as a result of the combined effects of a declining HIV death rate, and a sustained rate of new infections. Furthermore, HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy can expect to live nearly as long as uninfected persons (within 5 years) providing ample time for individuals to develop AIDS-associated and non–AIDS-associated hematologic and oncologic conditions. HIV-infected individuals remain at increased risk of AIDS-defining malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma, aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and invasive cervical cancer and a number of non–AIDS-defining malignancies, including Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as anemia and thrombocytopenia. When individuals present with any of these hematologic or malignant illnesses it should be the standard of care to obtain HIV testing so as to provide optimal treatment to both the presenting illness and the HIV.

Acronyms and Abbreviations

ABVD, Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; ADAMTS 13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with a thrombospondin type 1 motif, member 13; AMC, AIDS Malignancy Consortium; ART, antiretroviral therapy; AVD, Adriamycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone; BFU-E, burst-forming unit–erythroid; CFU-GM, granulocyte-macrophage colony-forming unit; CFU-GEMM, granulocyte-erythrocyte-monocyte and megakaryocyte colony-forming unit; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CHORUS, Collaboration in HIV Outcomes Research/U.S. study; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CODOX-M/IVAC, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate/ifosfamide, mesna, etoposide, cytarabine; CRF, circulating recombinant form; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CTL, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte; DHHS, Department of Health and Human Services; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EPOCH, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HHV8, human herpesvirus-8; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; hyperCVAD, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; IL, interleukin; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; KICS, KSHV-associated inflammatory cytokine syndrome; KSHV, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; nnRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; nRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PET-CT, positron emission tomography–computed tomography; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis; R-CHOP, rituximab plus CHOP; R-EPOCH, rituximab plus EPOCH; R-ICE, rituximab plus ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; SIV, simian immunodeficiency virus; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

HISTORY AND HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, is a lentivirus that originated as a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in chimpanzees and entered the human population in the early 20th century in equatorial Africa.1,2 First isolated in 1983,3,4 HIV-1 actually comprises four distinct viruses (types M, N, O, and P) that represent four separate transmission events that occurred between chimpanzees and humans, likely the result of predation of monkeys by humans and mucosal or nonintact skin contact with infected fluids. Group M, the viral type responsible for the HIV-1 pandemic, was detected in a tissue sample from 1959 and probably entered the human population in or around Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo (then Leopoldville, Belgium Congo) between 1910 and 1930 based on phylogenetic analysis.2 HIV-2 originated in West Africa, the result of cross-species transmission of SIV from sooty mangabeys to humans. Patients infected with HIV-2 progress more slowly and have lower plasma viral loads (often nondetectable) than those with HIV-1, reflective of the different virology and adaptation to humans of this SIV.5 Because of lower rates of replication and transmission, HIV-2 prevalence is declining and is being replaced by HIV-1 in countries where both viruses are endemic.5,6 Among those infected with HIV-1, group M is the globally predominant viral strain and is further divided into nine subtypes and many more recombinant viruses (circulating recombinant forms [CRFs]) with some geographic localization. Subtypes A and D predominate in East Africa; subtype C in South Africa, India, and Asia; subtype B in the Caribbean, the Americas, and Western Europe; and CRF01 in Southeast Asia.1

EPIDEMIOLOGY, TRANSMISSION

The development of Pneumocystis jiroveci (Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia and Kaposi sarcoma in previously healthy men who have sex with men on both coasts of the United States in 1981 represented the first clinical manifestations of HIV and the onset of the HIV-1 pandemic.7,8,9 Subsequent reports of similar illnesses in the sexual partners of index cases, injection drug users, patients with hemophilia and other transfusion recipients, infants born to infected mothers, and Haitian immigrants10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 helped identify the routes of transmission as bloodborne, sexual, or vertical. With the discovery of HIV in 1983 and the subsequent development of serologic testing, more systematic detection of HIV infections became possible providing an understanding of the regional and global HIV epidemiology. While sexual contact between men was responsible for most infections in the United States, Northern Europe, Australia, and parts of Central and South America, heterosexual spread predominated in sub-Saharan Africa and injection drug use followed by sexual transmission was responsible for most infections in Southern and Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia.18 Transmission rates between individuals per incident/act is dictated by the viral load in the HIV-infected person,19 the presence of modifying factors such as concurrent ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases and the type of exposure.20 Rates vary between 93 percent for blood transfusion from an infected person to less than 0.04 percent for oral sex. Estimated rates for mother-to-child transmission (in the absence of antiretroviral therapy [ART] prophylaxis) are 23 percent, for needle sharing 0.63 percent, for needle stick 0.23 percent, for receptive anal intercourse 1.38 percent, for insertive anal intercourse 0.11 percent, for receptive vaginal intercourse 0.08 percent, and for insertive vaginal intercourse 0.04 percent.20 In 2012 there were an estimated 35.3 million people living with HIV, including 2.3 million newly infected persons.21 Although the global incidence of HIV is thought to have peaked in 1997, the prevalence of HIV is increasing because of ongoing new infections and the shrinking death rate of those already infected and on ART (2.3 million deaths in 2005 versus 1.6 million deaths in 2012). The majority of HIV-infected persons (approximately 23 million) now live in sub-Saharan Africa with 4 million in Asia and Southeast Asia and roughly 3 million in the Americas and Caribbean.

PATHOGENESIS

Eighty percent of HIV infections occur via mucosal transmission during sex22 when cell-free and cell-associated virions transverse the epithelium to gain access to macrophages, Langerhans cells, dendritic cells, and CD4-expressing T lymphocytes.23 To infect most cells HIV must bind to CD4 and one of two major coreceptors (CCR5 or CXCR4); in most cases, CCR5-utilizing viral strains are those that are transmitted and predominate early in disease. Rare individuals who do not express CCR5 (homozygote for a 32 bp deletion mutation in the CCR5 gene) are highly resistant to HIV infection although they can be infected with isolates utilizing CXCR4. After transmission, low-level replication of HIV in tissue macrophages and dendritic cells can occur, but the key role these cells play is in trapping and trafficking virions and presenting them to CD4+ T lymphocytes within regional lymphatics (e.g., gut-associated lymphoid tissue and lymph nodes where the infection is amplified).24 High-level viral replication proceeds within these local tissues leading to profound CD4+ T-cell depletion, establishment of a reservoir of latently infected memory T cells and eventually to high plasma levels of virus that are the hallmark of acute infection. The immune response to HIV is brisk but ineffective and may, in fact, fuel the infection because the expression of inflammatory cytokines25 and migration of activated CD4+ T cells to the site of HIV-1 concentration provides additional activated cells that the virus coopts for its own replication.26 The initial antibody response to HIV does not contain neutralizing antibodies; these develop only later, months after chronic infection is established. Furthermore, HIV escapes these antibodies by mutations within N-glycosylation sites that prevent antibody binding.27 The CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) cell response to HIV controls high-level viral replication during primary infection and establishes the viral “setpoint” or plasma level of HIV RNA in chronic infection. Evidence for the controlling anti-HIV effect of CD8+ T cells includes their detection immediately prior to peak viremia, the development of viral escape mutations28,29,30 and the requirement for CD8+ T cells to control SIV infection in Rhesus macaques.31 The rate of viral escape mutations slows during chronic infection32,33 and is not associated with further declines in viral load, reaching a stalemate where viral replication continues under the pressure of a slowly evolving CTL response leading to viral strains with reduced replication capacity.34,35,36 As important as the direct cytolytic effect of HIV on CD4+ T cells, the virus induces a state of chronic immune activation of both the adaptive and innate immune systems that is central to disease pathogenesis.37,38,39,40,41 Because the immune response to HIV is defective and does not clear the virus, the immune system remains continually activated with high rates of T-cell turnover that eventually leads to T-cell exhaustion and depletion. This is particularly evident in gut-associated lymphoid tissue where early T-cell losses alter the integrity of the mucosal border leading to microbial translocation and leakage of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the blood which, in turn, amplifies the state of immune activation.42 This persistent, systemic inflammatory state leads to tissue fibrosis over time43,44 that is partly responsible for immune failure and the increased frequency of nonimmune, nontraditional chronic diseases that now plague an aging HIV population.45

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DISEASE PROGRESSION

Primary HIV infection that comes to medical attention presents as a febrile illness that may include headache, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, gastrointestinal symptoms, and rash and may be mistaken for mononucleosis or other nonspecific viral infections. Key to making the diagnosis is taking a history for HIV risk factors and obtaining appropriate laboratory testing (combined HIV Ag/Ab assays and plasma HIV RNA testing). However, in most cases, primary infection goes undiagnosed and patients are later identified in the chronic, asymptomatic phase of infection by routine screening or later still, after the development of symptoms that are often caused by opportunistic infections. Typically, the asymptomatic phase of chronic infection will last for 8 to 10 years, although there is great interindividual variation dictated by the effectiveness of the immune response in controlling HIV replication (the viral “setpoint,” see above). Long-term nonprogressors (those who maintain CD4+ T-cell counts >500 for 5 years without therapy) and elite controllers (those with low or nondetectable plasma HIV RNA without treatment) can live for decades with limited or no disease progression, while others with high viral setpoints in the range of 100,000 to >1,000,000 copies/mL can develop AIDS-defining illnesses quickly after primary infection. In untreated individuals CD4+ T-cell counts (typically at CD4 counts) typically decline by 50 to 100 cells/μL per year, taking 8 to 10 years before counts are in the range where symptoms develop (typically at CD4 count <500 cells/μL) or AIDS-defining illnesses occur (typically at CD4 count <200 cells/μL). Historically, opportunistic infections provided the first evidence for the existence of HIV and remain the most visible manifestation of infection in countries with limited access to ART and in individuals who are diagnosed late in the course of their disease. The development of opportunistic infections and AIDS-defining conditions is dependent on the virulence properties of the organism and the degree of host immune suppression. Pathogens with high virulence potential (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella sp., the bacterial agents of community-acquired pneumonia) cause disease in patients without HIV and do so in HIV-infected persons regardless of CD4 count (although more severe and prolonged illness occurs with more profound immunodeficiency). Agents with more limited pathogenic potential typically cause disease at lower CD4 counts, for example, P. jiroveci at CD4 counts below 200 cells/μL, while those that rarely cause disease in immunocompetent persons, such as disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex, Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis, and JC virus (the agent of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy), typically occur only in those with very advanced HIV disease and CD4 counts less than 100 cells/μL or less than 50 cells/μL, respectively (Table 81–1 lists HIV staging; Table 81–2 lists AIDS-defining conditions; and Table 81–3 lists common HIV-associated conditions by CD4 count). Prophylaxis against the development of these infections is provided when the infection is common and significant and when the prophylaxis is effective, inexpensive and well tolerated. (Table 81–4 lists the organisms and medications used for primary prophylaxis.) Tumors classified as AIDS-defining malignancies are Kaposi sarcoma, Burkitt lymphoma, immunoblastic lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma and cervical cancer, as these were first identified at high rates among infected persons early in the epidemic. Many other cancers also occur at increased rates among HIV-infected patients because of a higher rate of traditional cancer risk factors and the long-term effects of immune dysregulation leading to decreased tumor surveillance and chronic systemic inflammation. Outside of the immune defects levied by HIV, the virus can directly or indirectly cause specific organ or tissue damage including the nervous system (causing cognitive impairment, dementia and peripheral neuropathy), cardiovascular system (HIV cardiomyopathy), kidney (HIV nephropathy), gastrointestinal system (HIV enteropathy and cholangiopathy), and can accelerate disease progression as a result of other infections, such as hepatitides B and C.46,47 Finally, the long-term effects of chronic immune activation and persistent inflammation is likely a factor in the development of coronary artery disease,45 chronic liver disease,47,48 and a hypercoagulable state49,50,51 that is only partly corrected by the initiation of ART. These “aging effects” of HIV are likely to dominate the health issues for infected persons now that opportunistic infections are readily treated or avoided altogether through a combination of prophylaxis and ART.

Bacterial infections, multiple or recurrent* Candidiasis of bronchi, trachea, or lungs Candidiasis of esophagus† Cervical cancer, invasive§ Coccidioidomycosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary Cryptococcosis, extrapulmonary Cryptosporidiosis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration) Cytomegalovirus disease (other than liver, spleen, or nodes), onset at age >1 month Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision)† Encephalopathy, HIV related Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (>1 month’s duration) or bronchitis, pneumonitis, or esophagitis (onset at age >1 month) Histoplasmosis, disseminated or extrapulmonary Isosporiasis, chronic intestinal (>1 month’s duration) Kaposi sarcoma† Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia or pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia complex*† Lymphoma, Burkitt (or equivalent term) Lymphoma, immunoblastic (or equivalent term) Lymphoma, primary, of brain Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii, disseminated or extrapulmonary† Mycobacterium tuberculosis of any site, pulmonary,†§ disseminated,† or extrapulmonary† Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species, disseminated† or extrapulmonary† Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia† Pneumonia, recurrent†§ Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Salmonella septicemia, recurrent Toxoplasmosis of brain, onset at age >1 month† Wasting syndrome attributed to HIV |

| CD4 Count | Opportunistic Infection or Condition |

|---|---|

| >500 cells/μL | Any condition that can occur in HIV-uninfected persons, e.g., bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, varicella-zoster, herpes simplex virus |

| 350–499 cells/μL | Thrush, seborrheic dermatitis, oral hairy leucoplakia, molluscum contagiosum |

| 200–349 cells/μL | Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma |

| 100–199 cells/μL | Pneumocystis pneumonia, Candida esophagitis, cryptococcal meningitis |

| <100 cells/μL | Toxoplasma encephalitis, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, cytomegalovirus retinitis, primary central nervous system lymphoma, microsporidia |

| Infection | Criteria | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumocystis pneumonia | CD4 <200 cells/μL or <14% or oral candidiasis or an AIDS-defining illness | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or dapsone or aerosolized pentamidine |

| Tuberculosis | Purified protein derivative >5 mm or + Interferon-γ release assay | Isoniazid (INH) + pyridoxine |

| Toxoplasmosis | Immunoglobulin G+ and CD4 <100 cells/μL | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or dapsone+pyrimethamine+leucovorin |

| Mycobacterium avium complex | CD4 <50 cells/μL | Azithromycin or clarithromycin |

THERAPY

The story of ART from the first reports that zidovudine had activity against HIV to the current formulary of drugs, including single-tablet, fixed-dose, once-daily formulations, is one of the great achievements in medicine. Early studies of zidovudine monotherapy demonstrated a delay to the development of AIDS and short-term mortality benefits but no long-term effect on survival; zidovudine also carried significant toxicity.52,53,54,55,56,57 Combination therapy with other nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (nRTIs) proved slightly more effective than zidovudine alone, but not until combination nRTI was used with a third drug from another class, first nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (nnRTIs)58 and then protease inhibitors,59,60,61,62 were sustained viral suppression and substantive, dramatic improvements in survival realized.63 The recommended time to initiate ART has evolved in response to studies demonstrating benefits of ART at high CD4 counts and improvements in drug tolerability and formulation. Current Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines suggest that all HIV-infected persons be offered ART regardless of CD4 count, although the strength of evidence supporting this recommendation varies by CD4 count (Table 81–5 lists the criteria for initiating ART), while the World Health Organization sets a CD4 count threshold of 350 cells/μL for initiating ART in more resource-limited countries. The rationale for these expanded ART recommendations include the recognition that newer therapies are more convenient, have fewer adverse effects and are associated with lower rates of drug resistance. Furthermore, in addition to improved all-cause survival, ART preserves renal function in those with HIV-associated nephropathy,64 slows the progression of hepatic fibrosis in those coinfected with hepatitis C,65,66,67,68 decreases (but does not normalize) markers of chronic inflammation69 and may be associated with reduced cardiovascular disease,70 prevents the development of HIV-associated dementia,71,72 and is highly effective in reducing mother-to-child73,74 and sexual transmission.19,22,75 Adverse effects related to ART do occur but are less common with current regimens and can usually be effectively managed with corrective treatments and by substitution of the offending drug with an alternative medication.76,77 Similarly, the presence or development of drug resistance can usually be overcome by the use of secondary or salvage ART regimens that are fully suppressive. At the current time, only rare patients who are fully adherent to ART fail to control HIV replication. Treatment of early and primary infection provides a unique opportunity to intervene and possibly alter the course of HIV infection. Several studies have demonstrated that treatment in early or primary HIV lowers the rate of disease progression if treatment is subsequently interrupted78,79,80,81,82,83 and may also limit the size of the latent HIV reservoir,84,85,86,87 the impediment to curing patients. One interesting group of 14 patients initiated ART during primary infection and stayed on treatment for a median of 3 years and then controlled HIV replication for a median of 7 years after ART interruption.88 Finally, given the high viral loads typical of primary HIV, these patients are thought to be highly infectious; therefore identifying them and initiating treatment should prevent transmission to their uninfected partners. One consequence of initiating ART in the setting of a known or occult infection is the development of an acute inflammatory reaction as a result of reconstitution of the immune system in the presence of organisms or foreign antigens.89,90,91,92,93 The immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) occurs in between 8 and 30 percent of patients who start ART, depending on the opportunistic infection and the timing of ART.94 Risk factors for the development of IRIS include a low baseline CD4 count, more-severe disease and a short interval between treatment of the opportunistic infection and initiation of ART. The treatment of IRIS should include treatment of the underlying infection or condition, continued ART, and antiinflammatory medication, such as corticosteroids, depending on the severity of the reaction.95

| CD4 Count | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| <350 cells/μL | Start antiretroviral therapy (ART) (AI) |

| 350–500 cells/μL | Start ART (AII) |

| >500 cells/μL | Start ART (BIII) |

Clinical conditions favoring initiation of therapy regardless of CD4 count:

| |

PREVENTION AND CURE

The future of the HIV epidemic will differ by region and be dictated by local public health responses, HIV testing rates, sociobehavioral prevention interventions, and access to ART. Expanded HIV testing is an essential element of any prevention campaign as an estimated 50 percent of all new infections originate from individuals unaware of their HIV status.96 Behavioral interventions can have some preventative effect97,98,99 but biomedical methods have emerged as the most effective means to prevent new infections. Male circumcision can reduce female-to-male sexual transmission by 51 percent100 and is being implemented on a population level in some African countries. ART administered peripartum will prevent most mother-to-child transmissions101,102 and fully suppressive ART provided throughout pregnancy essentially eliminates all infant infections.73,74 A prospective randomized trial of HIV-discordant couples demonstrated that ART provided to the HIV-infected partner was almost 100 percent effective in preventing transmission22 and other studies have shown that elements of ART given to HIV-negative but at-risk persons (preexposure prophylaxis [PrEP]) can prevent HIV acquisition when subjects are adherent to treatment.103,104,105 These studies point the way to the best strategies and interventions to curtail the HIV epidemic until an effective HIV vaccine is available.

The persistence of replication-competent but transcriptionally silent HIV proviral DNA in long-lived resting cells (the HIV latent reservoir) is the impediment to cure for nearly all HIV-infected people.87,106,107,108,109 Although combination ART is highly effective at controlling HIV replication in activated cells, it has no effect on the latent HIV reservoir, which will persist as long as the cells harboring HIV survive. Because most HIV genomes reside in central and effector memory T cells that decay at a negligible rate, there is no possibility of cure with ART alone. The only individual cured of chronic HIV infection (Timothy Brown, the Berlin patient) developed acute myelogenous leukemia that was treated with high-dose conditioning and transplantation of HIV-resistant (CCR5D32/D32) allogeneic blood stem cells.109 While this case provides proof-of-principle that the latent HIV reservoir can be eliminated by allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, the approach is impractical for widespread application because of the high toxicity associated with this procedure, the morbidity of graft-versus-host disease, and the scarcity of CCR5D32/D32 donors. To date, most HIV cure efforts have focused on the strategy of reversing latency with the notion that once resting cells begin producing HIV they will be targeted by the immune system or die from apoptosis. However, early studies suggest that activating latent cells to express HIV does not reliably lead to their death and additional treatments including vaccination to boost cytotoxic responses will be needed.109A Gene therapy is also being pursued as a means to control or cure HIV; specifically, DNA editing enzymes that disrupt CCR5 have been used to eliminate CCR5 expression in cells that are then expanded ex vivo and reinfused into patients, creating a population of HIV-resistant CD4+ T cells.110,111

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS–ASSOCIATED MALIGNANCIES

When AIDS was first identified as a clinical syndrome it was quickly appreciated that these patients were at greatly increased risk for certain types of malignancies, including Kaposi sarcoma, various types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and invasive cervical cancer. Each of these AIDS-defining cancers is frequently associated with an oncogenic virus (Table 81–6). As effective ART was developed and patients began living into their 50s, 60s, and 70s,112,113 it became apparent that many non–AIDS-defining malignancies were also more common in this population compared to HIV-uninfected patients. Anal cancer is 120-fold more common in people living with HIV, particularly among men who have sex with men. Hodgkin lymphoma incidence is increased approximately 20-fold, hepatocellular cancer fivefold, and the risk of lung cancer is increased twofold. In contrast, the risks of other common cancers, including breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colon cancer, are not increased in comparison to HIV-negative people.114 In the ART era, non–AIDS-defining malignancies comprise approximately half of the cancers in people living with HIV, and overall cancer causes approximately 25 to 33 percent of all deaths in HIV-infected patients, supporting the importance of age-appropriate standard cancer screening.115

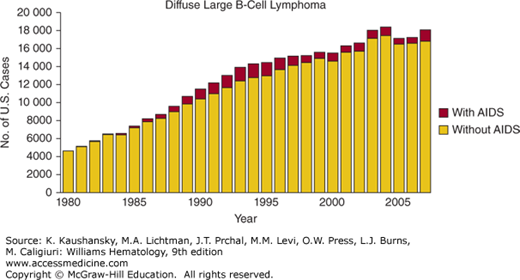

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that 20 percent of HIV+ people in the United States do not know that they are HIV+,116 and HIV testing is strongly recommended in all patients who present to the hematologist with NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), or other malignancies.117 This recommendation is made because approximately 5 percent of those with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and 22 percent of patients with Burkitt lymphoma in the United States are HIV+ (Fig. 81–1). These proportions vary substantially by demographic group118: among men, 10 percent of those with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are HIV+, in contrast to 1 percent of women, and approximately 40 percent of those 30 to 59 years old with Burkitt lymphoma are HIV+. It is important to diagnose HIV infection when present, as effective treatment of HIV is essential for successful treatment of the malignancy or ITP.

Figure 81–1.

Number of AIDS-defining cancer cases in the United States in persons with and without AIDS by calendar year. (Reproduced with permission from Shiels MS, Pfeiffer RM, Hall HI, et al.: Proportions of Kaposi sarcoma, selected non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and cervical cancer in the United States occurring in persons with AIDS, 1980-2007. JAMA 13;305(14):1450–1459, 2011.)

Among HIV+ patients in the United States, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is now more common than Kaposi sarcoma, although Kaposi sarcoma remains the most common malignancy in people living with HIV worldwide.118 The pathophysiology of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in HIV has been reviewed.119,120 In a recent case series, HIV+ patients presented with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma at a median age of 43 years, 2 decades younger than HIV– patients.121 Patients often present with a rapidly growing lymph node or extranodal mass, and frequently have B symptoms (drenching night sweats, fever, or loss of 10 percent of body weight). Involvement of extranodal sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, liver, CNS, lung, and other sites is common.121,122 Diagnosis is most commonly made by excisional lymph node biopsy. Evaluation should include careful examination of all lymph nodes sites, and the oral cavity. Standard staging with positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT), marrow evaluation, and lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid cytology and flow cytometry123 should be performed. Patients should be evaluated for hepatitis B prior to initiation of chemotherapy. If active hepatitis B is found (hepatitis B DNA+), it must be managed in the context of the HIV treatment, as several commonly used medications for hepatitis B are also active against HIV. Although initial studies in the pre-ART era focused on low-dose chemotherapy,124 it is now appreciated that full-dose multiagent systemic chemotherapy with appropriate supportive care using filgrastim or peg-filgrastim and prophylaxis against infectious complications, offers the best chance for permanent cure. Cohort studies show that the 5-year overall survival in the ART era is far better than the pre-ART era.125 A National Cancer Institute study using six cycles of dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH), in which the initial cyclophosphamide dose was adjusted based on the CD4 count, and subsequent cycles cyclophosphamide dosing was adjusted based on the neutrophil nadir, showed an overall survival of 60 percent at 53 months (39 patients, 79 percent had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 18 percent had Burkitt lymphoma, and none were on ART during chemotherapy).126 CD4 counts dropped by 190 cells/μL during chemotherapy, but recovered to baseline by 6 to 12 months following chemotherapy. All patients received P. jiroveci prophylaxis, and if CD4 counts were less than 100 cells/μL, M. avium complex prophylaxis. All patients also received filgrastim following each cycle of chemotherapy. This key study demonstrated that EPOCH is safe and effective in HIV+ patients with aggressive lymphoma. Outcomes differed markedly depending on the initial CD4 count: patients with an initial CD4 count greater than 100 cells/μL had an 87 percent overall survival at 53 months, whereas those with CD counts of less than 100 cells/μL had a 16 percent overall survival at 53 months.126 A larger multiinstitution study done by the AIDS Malignancy Consortium (AMC-034) randomized patients to receive EPOCH with concurrent rituximab versus EPOCH with sequential rituximab (given weekly for 6 weeks following completion of EPOCH) in 101 patients with HIV-associated NHL (approximately 75 percent of the patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and 25 percent had mainly Burkitt lymphoma).127 Administration of EPOCH with concurrent rituximab resulted in a high complete response rate (73 percent) in comparison to EPOCH with sequential rituximab (55 percent complete response rate). The National Cancer Institute evaluated short-course EPOCH with dose-dense rituximab (rituximab day 1 and day 5 of each cycle of EPOCH), and achieved an overall survival of 68 percent at 5 years in 33 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.128 In this study, the initial cyclophosphamide dose was 750 mg/m2 (even in those patients with a low CD4 count) and was dose adjusted, depending on the neutrophil nadir, in subsequent cycles of EPOCH. Patients were treated to complete response plus one additional cycle. The majority (79 percent) of patients received three cycles of short-course EPOCH with dose-dense rituximab, and ART was suspended during chemotherapy because of concern about alteration in the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of the chemotherapy agents or overlapping toxicity. CD4 counts dropped a median of 64 cells/μL, and recovered to baseline by 6 to 12 months. Consistent with other studies, patients with initial CD4 counts of 100 cells/μL or greater had a much better 5-year overall survival (90 percent) than did the patients with a CD4 count of less than 100 cells/μL (20 percent). Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) has also been studied in HIV+ patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In an AMC phase III multiinstitution clinical trial (AMC 010), patients with HIV-associated NHL (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in 80 percent, Burkitt lymphoma in 9 percent) were randomized to six cycles of CHOP (n = 50) versus rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP) (n = 99), with all patients on ART.129 The R-CHOP group also received three monthly doses of rituximab following completion of chemotherapy. Of note, the median CD4 count at enrollment was 133 cells/μL and 24 percent of the patients had advanced HIV with CD4 counts less than 50 cells/μL, so this was a fairly immunocompromised group of patients. Overall survival was identical with CHOP or R-CHOP, unlike HIV-negative patients in whom the addition of rituximab significantly improves outcome. In the AMC 010 clinical trial, there were significantly more deaths from infection in the R-CHOP arm in comparison to the CHOP arm, which offset the trend toward better control of lymphoma with R-CHOP. The majority of these infectious deaths occurred in patients with a CD4 count of less than 50 cells/μL, suggesting that rituximab should be used cautiously in immunologically vulnerable patients. As in studies of EPOCH, patients with a CD4 count greater than 100 cells/μL had a better overall survival than those with a lower CD4 count. Other reports suggest that R-CHOP treatment in HIV+ patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is safe and effective,121,130 including in those with a low CD4 count.131 In a phase II study of modified R-CHOP in 40 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin was substituted for doxorubicin132 and the complete response rate was 48 percent, lower than what is reported with rituximab plus EPOCH (R-EPOCH) or R-CHOP. At the time of this writing, there are no phase III data comparing R-EPOCH to R-CHOP in HIV+ patients. Pooled analysis of two sequential AMC clinical trials, AMC 010 (99 patients on the R-CHOP arm) and AMC 034 (51 patients on the concurrent R-EPOCH arm) showed that the 2-year overall survival was approximately 50 percent with R-CHOP and approximately 65 percent with R-EPOCH (p <0.01), suggesting superiority of R-EPOCH.133 Similarly, a pooled analysis of 1546 patients enrolled in 19 prospective clinical trials, concluded that EPOCH was associated with a better overall survival than CHOP in patients with HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (hazard ratio 0.33, p = 0.03).134 However these observations require validation in prospective randomized studies. For patients with relapsed or refractory HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, salvage regimens such as gemcitabine/dexamethasone/cisplatin135 or etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin (ESHAP)136 can provide response rates of approximately 50 percent.

HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma is approximately one-third as common as HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the Western world, and occurs at a higher CD4 count.137 In a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Registry–based study, there was an increase in the number of cases of Burkitt lymphoma in the United States in the late 1980s that is maintained to the present time (see Fig. 81-1), particularly in men, and is thought to be attributable to the HIV epidemic.138 The pathogenesis of HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma is similar to that of Burkitt lymphoma in HIV– people, and involves translocation of the Myc gene on chromosome 8 with one of the immunoglobulin genes on chromosomes, 2, 14, or 22, resulting in overexpression of Myc.139 HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma is an aggressive malignancy, and it is important to act decisively in these often very ill patients. More than 80 percent of patients with HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma present with stage IV disease140 and extranodal sites are often involved. Marrow, liver, gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and CNS involvement are common, with cranial nerve palsies a common feature of CNS involvement.141 The serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is elevated in more than 80 percent of patients, often to high levels (greater than fivefold normal). A number of chemotherapy regimens have been studied in HIV+ patients with Burkitt lymphoma. As in the HIV– setting, CHOP is not adequate treatment for Burkitt lymphoma,140,142 and should not be used. Recent data show excellent outcomes with a variant of the R-EPOCH regimen.143 In this single-institution, small prospective clinical trial, a total of 30 patients with Burkitt lymphoma were treated, including 11 who were HIV+ with a median CD4 count of 322 cells/μL. The short-course EPOCH-RR used in this clinical trial included two doses of rituximab per cycle of EPOCH, and a total of three or four cycles of EPOCH (to complete response plus one additional cycle), and included prophylactic intrathecal methotrexate. With a median follow up of 6 years, the overall survival of the HIV+ patients was 90 percent. The major toxicity was neutropenia in 31 percent of cycles of EPOCH-RR, and hospital admission for febrile neutropenia was required in 10 percent of cycles. This study showed that low-intensity therapy administered primarily in the outpatient setting can be effective for HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma. Other studies of R-EPOCH that included a subset of patients with HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma also report excellent outcomes with R-EPOCH.127 Other regimens reported in patients with HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma include cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (HyperCVAD) alternating with high-dose methotrexate plus cytarabine.144 In this study, patients were very immunocompromised with a median CD4 count of 77 cells/μL; nevertheless, complete remission was achieved in more than 90 percent of patients, with 48 percent of patients alive at 2 years. Severe myelosuppression was universal, but infectious complications were similar to HIV– patients. In this small study, those on ART had a better outcome than those not on ART. Cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, methotrexate/ifosfamide, mesna, etoposide, cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC) has also been employed to treat HIV-associated Burkitt lymphoma,145,146,147 with 3-year overall survival of approximately 50 percent.146 A retrospective review compared eight HIV+ patients who received CODOX-M/IVAC to 24 HIV– patients with Burkitt lymphoma145: Patients had similar rates of myelosuppression, infection, and complete response regardless of HIV status. The LMB86 protocol (including high-dose methotrexate plus cytarabine) was used to treat HIV-related Burkitt lymphoma141 in a prospective single center study of 63 patients on ART. The complete response rate was 70 percent and the estimated disease-free survival at 2 years was 67 percent. This regimen was characterized by severe marrow toxicity, and more than 10 percent of patients died of regimen-related toxicity. Poor prognostic factors included a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/μL and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of greater than 2. Other intensive regimens have also been used, with 4-year overall survival of 70 percent, but with death in 11 percent from regimen-related toxicity.148

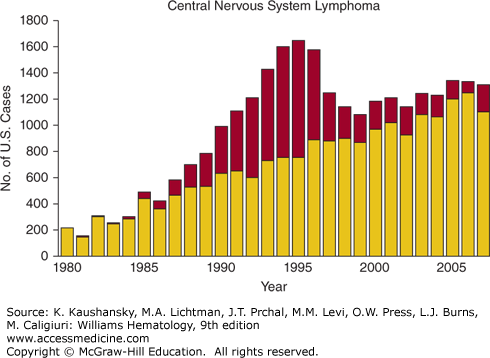

Primary CNS lymphoma in HIV+ patients is an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma occurring in the brain, typically in patients with very advanced HIV: These patients usually have a CD4 count of less than 50 cells/μL, and often of less than 20 cells/μL.137,149,150,151 The epidemiology of primary CNS lymphoma illustrates the concept of specific types of lymphoma occurring at different levels of immunodepletion. The incidence of primary CNS lymphoma has declined markedly since the availability of ART (see Fig. 81–1).150,152 The pathophysiology of HIV-associated primary CNS lymphoma is related to EBV which is detectable in virtually all cases.139 Primary CNS lymphoma should be considered in an HIV+ patient who presents with neurologic symptoms (confusion, cognitive decline, memory loss), headache, seizures, or ataxia. In one series, the most common symptom was headache, followed by memory loss, ataxia, and seizure.153 Characteristic features on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain include a single to several mass lesions in the subcortical white matter.154 Anatomic sites commonly involved are predominantly the cerebral cortex and periventricular area, but the basal ganglia can be involved in up to one-third of cases. Cerebellar or brain stem involvement is rare.150 A thorough physical exam for signs of systemic lymphoma is key, including a testicular exam as testicular lymphoma frequently involves the CNS. A slit-lamp exam to assess for vitreous disease should be done; this may assist in diagnoses of primary CNS lymphoma and may affect therapy. Evaluation with a chest, abdomen, and pelvic CT and a marrow aspirate and biopsy should be performed. If a lumbar puncture can be safely done, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) should be sent for cytology and flow cytometry to evaluate for leptomeningeal involvement with lymphoma, and also for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for EBV. Detection of EBV in the CSF supports, but does not confirm, the diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma in these patients.155 PET-CT of the brain can also help distinguish primary CNS lymphoma from other common causes of focal brain lesions in profoundly immunosuppressed patients with HIV, namely, cerebral toxoplasmosis and other infections.156,157 Evaluation of HIV+ patients with CNS mass lesions should include blood serology for toxoplasmosis, although a small percentage of patients with CNS toxoplasmosis will have negative serologies. Stereotactic brain biopsy should be performed if possible, but some lesions are not readily accessible to biopsy; in these cases, the diagnosis of primary CNS lymphoma may rest on CSF cytology, detection of EBV in the CSF, and the results of PET-CT. Because of the rarity of primary CNS lymphoma in the ART era, there are no large prospective clinical trial data to define optimal therapy. Case reports document long-term responses to initiation of ART as a sole intervention in a small number of patients who refused other therapy. All HIV+ patients with primary CNS lymphoma should be on effective ART. Systemic glucocorticoid treatment can temporarily ameliorate symptoms. Small retrospective series report that whole-brain radiation therapy can result in improved survival,149 but approximately one-third of these patients had detectable leukoencephalopathy on followup. A large retrospective study found that treatment with whole-brain radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy was associated with a decreased risk of death,151 but this analysis is confounded by lack of information on performance status. Small numbers of patients have been treated with multiple cycles of high-dose methotrexate with leucovorin rescue, without radiation therapy, with prolonged survival and no cognitive dysfunction,158,159 and this may be a reasonable option in patients with good performance status. In the pre-ART era, median survival of the HIV+ patient with primary CNS lymphoma was approximately 2 months. The outcome has improved in the present era, but remains inferior to that of patients without HIV.153 The Center for AIDS Research database for 1996 to 2010 shows that the 2-year survival of HIV+ patients with primary CNS lymphoma was 24 percent, inferior to other major types of HIV-associated lymphoma (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma).137 Prior CNS opportunistic infection151 and poor performance status149,150 confer an increased risk of death.

Described in 1997,160 plasmablastic lymphoma is a rare and very aggressive B-cell NHL with plasmacytic differentiation that often involves the oral cavity, typically the gingiva and the palate. In the original report, 15 of the 16 cases were HIV+, and subsequent studies showed that plasmablastic lymphoma comprises approximately 2 to 3 percent of NHL in people living with HIV.161 A review of 112 cases of HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma showed that the median age of presentation was approximately 40 years, and the median CD4 count was approximately 180 cells/μL. Of the 112 patients, 58 percent had primary oral involvement. Other common sites of involvement were the gastrointestinal track, the lymph nodes and skin, among other sites.162 In a recent series of 50 cases of plasmablastic lymphoma,163 approximately 25 percent of the patients had oral cavity involvement, and extraoral involvement was common. Diagnosis requires biopsy. The pathology shows a monomorphic diffuse lymphoid infiltrate with cells resembling plasmablasts. The cells have a high proliferative rate with a Ki-67 often exceeding 90 percent, and are positive for plasma cell markers. CD20 is expressed in 2 percent or fewer of the cases and the majority of the cases (>80 percent) are EBV+. The differential diagnosis of an oral cavity lesion in a person with HIV includes odontogenic infection, squamous carcinoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or Burkitt lymphoma.

Many of the patients with plasmablastic lymphoma have been treated with CHOP or with EPOCH, with poor outcome. In one retrospective series,163 median overall survival was 11 months with no difference in outcome between CHOP versus more intensive chemotherapy (EPOCH, hyperCVAD, or other regimens). Data from the German AIDS Related Lymphoma Cohort Study in the ART era confirmed the poor outcome of these patients, with a median survival of 5 months.164 There are no prospective clinical trials to define optimal treatment for patients with HIV-associated plasmablastic lymphoma. Case reports of individual patients suggest that bortezomib may have activity in these patients, and this should be explored in future clinical trials.165,166

Primary effusion lymphoma is an aggressive B-cell lymphoma characterized by lymphomatous effusions in body cavities, most commonly pleural effusion,167,168 followed by ascites and pericardial effusion or multiple body cavities; lymph nodes, marrow, and skin can also be involved. A solid variant of primary effusion lymphoma presents without effusion, but with lymph node, gastrointestinal, skin, or liver involvement has been reported.169 Primary effusion lymphoma comprises approximately 4 percent of HIV-associated NHL170 and occurs much more frequently in men than in women (10:1 ratio), usually associated with low CD4 counts (50 to 200 cells/μL).171 Of primary effusion lymphoma cases, 100 percent are human herpesvirus-8+ (HHV8+), and approximately 80 percent are EBV+. HHV8 plays a key pathophysiologic role, possibly by elaboration of a viral homologue of FLICE inhibitory protein and a viral homologue of interleukin (IL)-6.120 Other HHV8-related disorders include Castleman disease and Kaposi sarcoma, both of which may coexist with primary effusion lymphoma in a substantial proportion of patients.168 Patients may present with dyspnea from pleural effusions or new-onset ascites. A high index of suspicion for lymphoma is needed so that appropriate samples are sent to Hematopathology for analysis. Primary effusion lymphoma cells have an immunoblastic, plasmablastic, or anaplastic appearance and are CD45+ and CD30+; CD20 is expressed less than 5 percent of the time. The malignant cells are latently infected with HHV8, which is detectable by immunocytochemistry. There are no large prospective studies of treatment of primary effusion lymphoma, a consequence of its rarity, and the majority of the available information is derived from retrospective case series. There are a few case reports of complete remission following initiation of ART without chemotherapy, and ART should be a component of the treatment plan. Patients have been treated with CHOP, EPOCH, and other regimens. Approximately 50 percent of patients with primary effusion lymphoma achieve a complete response, but relapse within the next few months is common, and the median survival is approximately 6 months, with most deaths a result of progressive lymphoma. In one series, poor prognostic features included an ECOG performance status greater than 2 and ART noncompliance. Promising preclinical data show that treatment with the anti-CD30 agent brentuximab vedotin172 or bortezomib with or without vorinostat173 can decrease growth of primary effusion lymphoma cell lines and prolong survival in a mouse xenograft model.

As ART improves, the prognosis for patients with HIV-associated NHL is defined mainly by lymphoma-related features, and less by HIV.121 A retrospective review of patients with HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma diagnosed in the pre-ART era (120 patients), and in the ART era (72 patients) showed a median survival of 8 months in the pre-ART era and 43 months in the ART era; this held true for each of the different International Prognostic Index groups.125 Pooled data for 1546 patients with HIV-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or Burkitt lymphoma who had been enrolled in phase II or phase III clinical trials was evaluated to identify treatment-related factors associated with overall survival. The use of rituximab was significantly associated with improved overall survival (hazard ratio 0.55, p <0.001) for patients with a CD4 count of greater than 50 cells/μL but not for those patients with CD4 counts of less than 50 cells/μL. A focus on the 1059 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma suggested that treatment with EPOCH resulted in a better overall survival (hazard ratio 0.33, p = 0.031) than treatment with CHOP. On multivariant analysis of R-EPOCH versus R-CHOP, the hazard ratio for overall survival was 0.34 favoring R-EPOCH, although this did not achieve statistical significance. An enhanced internal prognostic index based on 650 adults with de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated at seven National Comprehensive Cancer Network Cancer Centers in the rituximab era included a small portion of HIV+ patients.174

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree