18320

Head and Neck Cancer in Older Adults

Ronald J. Maggiore, Noam VanderWalde, and Melissa Crawley

Head and neck cancers (HNCs) usually manifest as squamous cell carcinomas within the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, oral cavity, pharynx (nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx), and larynx. In 2016, there will be an estimated 61,760 new cases of oral cavity/pharynx and larynx cancers and 13,190 related deaths in the United States (1). Despite the increasing trend of human papilloma virus (HPV)-related cancers (usually oropharynx) in younger patients (2,3), HNC remains primarily a cancer of older adults (median age at diagnosis = 62 years) (4). In addition, the incidence of newly diagnosed HNC among older adults is expected to increase by more than 60% by the year 2030 (5).

Treatment decision making for older HNC patients remains difficult, and “gold-standard” treatments are not well defined. The majority of HNC patients present with locoregionally advanced (LA; stages III and IVA-B) disease, often warranting multimodality therapy such as concurrent chemoradiation (CRT) (6). These treatments often lead to significant acute and late-term toxicities, which can impact treatment adherence, quality of life (QOL), and survival. Thus, older and/or functionally vulnerable patients are often considered poor candidates for multimodality treatment and are subsequently less likely to receive standard-of-care therapy compared to their younger counterparts (7,8). This dichotomy is also evident in radiation therapy (RT) practices for older HNC patients (9).

OLDER ADULTS WITH HNC: LACK OF A ROBUST EVIDENCE BASE

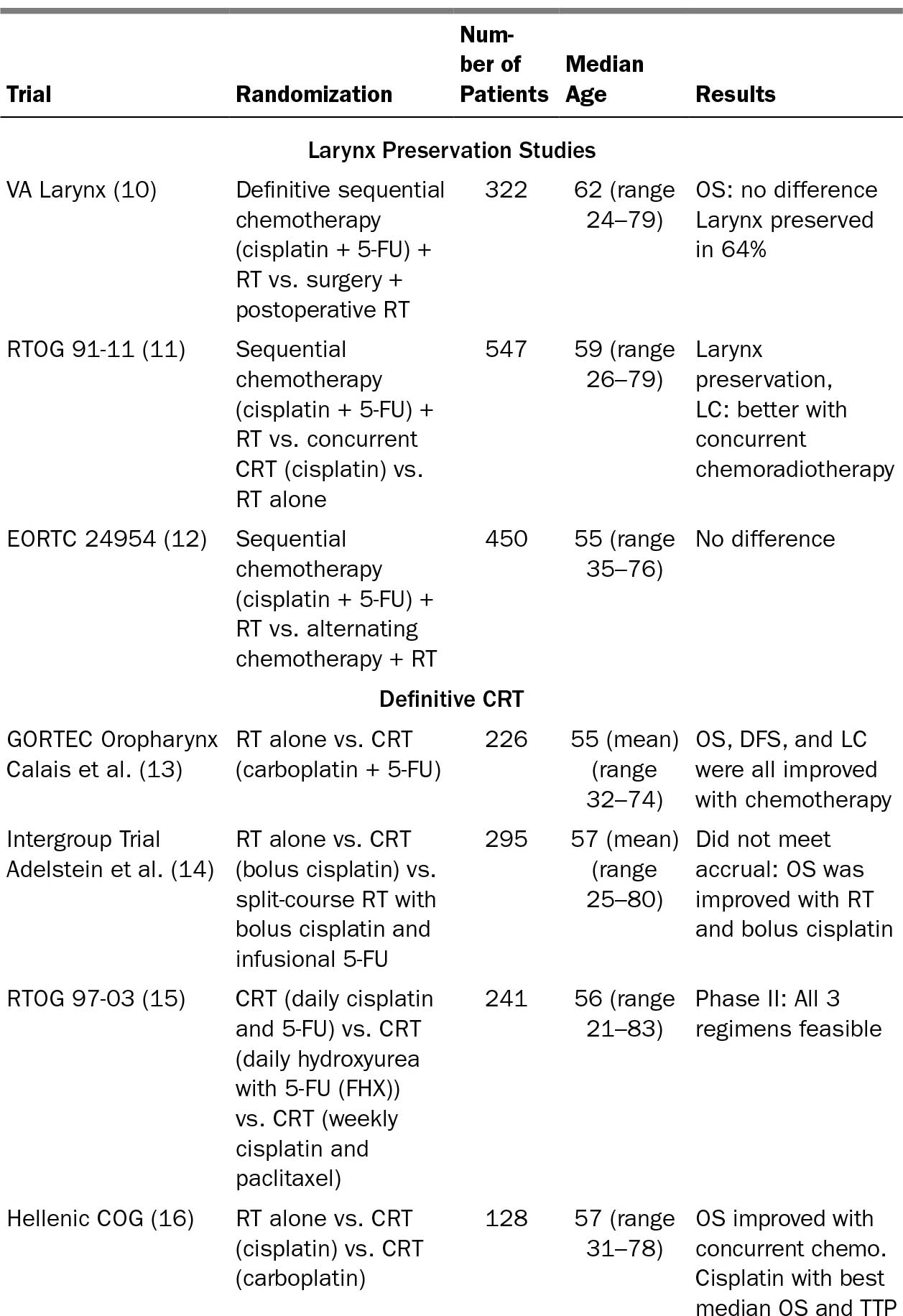

Despite older adults being disproportionately affected by HNC, the evidence base for treatment decision making in older adults with HNC remains insufficient because existing clinical trial data included few adults age 65 years or older (Table 20.1), and older adults remain underrepresented or underaccrued in cancer clinical trials in general (Table 20.2) (22,23). Age-related changes in swallowing and physical function with concomitant rise of comorbidity makes this a vulnerable patient population in light of the inherent intensity of combined modality treatments commonly employed for HNC. For example, advanced age increases the risk of acute RT-related dysphagia in HNC, and baseline dysphagia is an independent risk factor for later RT-related dysphagia (24). In addition, more than 80% of patients with HNC, irrespective of age, develop sarcopenia by the time they complete definitive RT or CRT (25,26). Long-term sequelae from such therapies can have significant impacts on functional outcomes (27).

184TABLE 20.1 Inclusion of Older Adults in Representative Seminal HNC Clinical Trials

185

186TABLE 20.2 Select Ongoing Clinical Trials Targeting Older Adults With HNC (as of March 30, 2016)

Study Name | Patients | Outcomes Being Studied |

EGESOR: Impact of Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment on Malnutrition, Functional Status and Survival in Elderly Patients With Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas (HNSCCs): a Randomized Controlled Multicenter Clinical Trial (//clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02025062) (Multi-center, France) | Age: ≥65 y Function: N/A Cancer: Any SCCHN diagnosis | Primary: Composite: OS + loss ≥ 2 ADL points + ≥10% weight loss Secondary: Hospitalization, PFS, HR-QOL (up to 24 mo) |

ELAN-RT: Non Inferiority Trial of Standard RT Versus Hypofractionated Split Course in Elderly Vulnerable Patients With Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer (GORTEC-ELAN-RT) (//clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01864850) (Multi-center, France) | Age: ≥70 y Function: Baseline GA: “Unfit,” ECOG PS 0-1 Cancer: Stages II-IVB SCCHN Treatment: RT alone: Standard: 70 Gy/2 wk vs. Experimental: hypofractionated 55 Gy/7 wk (2.5–3 Gy per fraction per protocol) | Primary: Locoregional control (6 mo) Secondary: OS, PFS, DC, ADL impairment, HR-QOL, safety/toxicity (up to 18 mo) |

ELAN-FIT: Phase II Multicenter Trial Evaluating First Line Carboplatin, 5-Fluorouracil and Cetuximab in Patients With Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer, Aged 70 and Over, Ranked as Fit (No Frailty) by Geriatric Assessment (//clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01864772) (Multi-center, France) | Age: ≥70 y and Cr Cl ≥ 50 (MDRD) Function: Baseline GA: “Fit,” ECOG PS 0-1 Cancer: R/M SCCHN except NPC, SNC Treatment: EXTREME (carboplatin/5-FU/cetuximab × six cycles, followed by cetuximab maintenance) | Primary Outcomes: ORR + safety/toxicity (at 1 and 3 mo postchemo) and < 2 point loss in ADLs (at 1-mo postinitial chemo) Secondary: Best ORR, OS, PFS, response duration on maintenance, safety/toxicity maintenance (up to 1 y); HR-QOL, ADL, IADLs up to 1-mo posttreatment |

ELAN-UNFIT: Multicentric Randomized Phase III Trial Comparing Methotrexate and Cetuximab in First-line Treatment of Recurrent and/or Metastatic Squamous Cell Head and Neck Cancer in Elderly Unfit Patients According to Geriatric Evaluation (//clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01884623) (Multi-center, France) | Age: ≥70 y and CrCl > 50 (MDRD) Function: Baseline GA: “Unfit,” ECOG PS 0-2 Cancer: R/M SCCHN except NPC, SNC Treatment: Weekly cetuximab vs. weekly methotrexate | Primary Outcomes: ORR + safety/toxicity (at 1 and 3 mo postchemo) and < 2 point loss in ADLs (at 1-mo postinitial chemo) Secondary: Best ORR, OS, PFS, response duration on maintenance, safety/toxicity maintenance (up to 1 y); HR-QOL, ADL, IADLs up to 1-mo posttreatment |

187ADLs, activities of daily living; CrCl, creatinine clearance; CRT, chemoradiation; DC, distant control; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; GA, geriatric assessment; HNC, head and neck cancer; HNSCCs, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas; HR-QOL, health-related quality of life; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; MDRD, modification of diet in renal disease calculation; N/A, not applicable; NPC, nasopharynx cancer; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; R/M, recurrent/metastatic; RT, radiation therapy; SCCHN, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck; SNC, sinonasal cancer.

RISK FOR ADVERSE EVENTS: THERAPY-RELATED ISSUES FOR OLDER ADULTS WITH HNC

Localized Disease

Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for early-stage HNCs. Even among locally advanced cancers of the oral cavity, initial surgical management is often preferred. The evolution of transoral robotic surgery (TORS) has allowed this technology to be implemented to treat select early-stage and LA cases of oropharyngeal cancers, thereby potentially avoiding adjuvant RT/CRT and their associated toxicities. However, for those patients with unresectable primary tumors, or obvious extracapsular extension on imaging, adjuvant CRT will be required after resection, and thus the benefit of TORS over upfront CRT is questionable. For aggressive T4 tumors of the larynx, upfront total laryngectomy may still confer the best long-term disease control (28). Moreover, age may not be as critical as other risk factors for perioperative morbidity, but mortality may still be higher in patients aged 70 years or older (29,30).

Definitive RT for early-stage cancers may represent an alternative to surgery in select patients, particularly those with laryngeal cancers, with good cancer control and likely better voice preservation (31,32). Patients with T1/T2N0 glottic cancers have 188excellent long-term results from hypofractionated RT alone, often with less morbidity (28). Additionally, patients with T1/T2N0 tonsillar primaries have historically had excellent local control and survival with RT alone (30,31). Although many of these early-stage HNC patients are now being approached with surgery first (32), in older patients who may be poor surgical candidates, RT alone, especially when it can be employed unilaterally, can confer a more optimal risk/benefit balance (33,34).

LA Disease

Organ-preservation approaches utilizing RT and CRT have become preferred in many cases of LA-HNC involving certain sites in order to avoid perioperative morbidity, potentially maintain long-term speech and swallowing function, and reserve surgery as salvage therapy for local recurrences. CRT has been preferred over RT for LA oropharynx cancers as well as larynx cancers, particularly with improved locoregional control and improved laryngectomy-free survival. However, overall survival may not be better and in some cases may be worse with CRT (RTOG 91-11) (35). The incremental survival benefit that chemotherapy confers when combined with concurrent RT is small (6.5%), and becomes less with advancing age, particularly in patients age greater than 70 years (36). Subsequent studies have offered further mixed results on the benefit of the addition of chemotherapy or cetuximab to RT in older adults with LA-HNC (37–39). However, single-institution retrospective studies have shown that select older patients with LA-HNC may still derive benefits from CRT (40,41).

A combined analysis of two large randomized trials (42,43) showed that adjuvant RT or CRT is largely determined by presence of “high-risk” pathologic features (i.e., positive surgical margins, extracapsular extension). It is important to note that older HNC patients were significantly underrepresented in these two trials. Furthermore, we know that the addition of chemotherapy can increase the acute treatment-related toxicities 2- to 3-fold, and long-term small improvements in overall survival must be weighed carefully in more functionally vulnerable/frail patients and/or those with multimorbidity. The benefit of the addition of cetuximab as systemic therapy to adjuvant RT in HNC patients whose cancers have “intermediate-risk” pathologic features (e.g., lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion) is part of RTOG 0920, which does not exclude older adults based on chronologic age but is limited to those with a performance status of 0 to 1 (44).

Recurrent/Metastatic (R/M) Disease

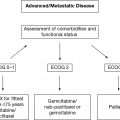

For most recurrent and all metastatic HNC cases, chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment. Older adults may tolerate combination chemotherapies well but may be at risk for specific toxicities (45). It is important to note the studies showing that virtually all combination chemotherapies can improve response rates and progression-free survival, but not overall survival compared to monotherapies (46). It was not until the EXTREME trial that the addition of cetuximab to platinum/5-fluorouracil showed the addition of an agent to improve overall survival (47). However, the toxicity of a triplet regimen in younger adults coupled with paucity of data in older adults (<20% of patients enrolled were age ≥ 65 years) makes such a regimen unwieldy in 189common clinical practice for many older or functionally vulnerable younger adults with metastatic HNC. It will be important in the future to evaluate more targeted or immunotherapeutic agents, including PD-1 inhibitors such as pembrolizumab, which has efficacy even in heavily pretreated patients (48), especially in older adults who may not otherwise be suitable candidates for “traditional” systemic therapeutic options.

For select local or locoregional recurrences, surgery with RT or CRT can be considered for salvage on a case-by-case basis. In patients who have local failure after remission, there is an estimated 50% to 60% mortality rate (49). Historically, salvage surgery is the pillar of treatment, with local control rates of 60% to 70%; however, surgery may not be an option for many patients because of disease spread, critical anatomic involvement, and poor QOL (50,51). Re-irradiation with chemotherapy (CRRT) in carefully selected patients still results in poor survival and high rates of major toxicities (52). Two phase II trials evaluating the efficacy of CRRT have been conducted: RTOG 9610 (53) (median age = 62 years) and RTOG 9911 (median age = 60 years) (54). Grade 3 to 5 toxicities with CRRT were 25% to 36% (8%–11% grade 5 = death) with 2-year survival only 15% to 25% (53,54). Standard techniques for RT delivery are limited by dose tolerance limitations of traditional surrounding tissues, with significant risk for late-term toxicities, including cervical fibrosis, osteoradionecrosis, trismus, and carotid hemorrhage (55). However, stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) techniques have been developed in this setting (56) to improve feasibility of re-irradiation and decreases treatment time, which may be appealing for older adults (56).

FUNCTIONAL AND GERO-CENTRIC ISSUES FOR OLDER AND AT-RISK YOUNGER ADULTS WITH HNC

Late-term effects of HNC therapy can have a profound impact on the QOL of survivors irrespective of age, including adverse effects on speech, swallowing, and nutrition (27). Older adults with HNC who received RT or CRT, compared to younger adults, have worse self-reported physical performance measures (57). Age, cochlear RT dose, and use of cisplatin-based CRT increases the risk of ototoxicity, which can persist long term (58). Coupled with the aforementioned prevalence of sarcopenia, malnutrition with attendant short- and long-term risks for aspiration and gastrostomy tube dependence remain critical aspects for ongoing care. However, exercise- and/or nutrition-based intervention studies to mitigate the toxicities of RT/CRT remain sparse even among younger HNC patients (59).

Another approach is to incorporate geriatric assessment (GA) tools, validate them, and utilize predictive findings to tailor HNC therapy intensity and/or supportive care interventions. GAs are only recently being evaluated in the context of older adults with HNC. Pilot data have shown that a GA may not necessarily be as predictive of toxicity in older adults with HNC undergoing RT or CRT, but instrumental activities of daily living impairment may be a predictor (60). Serial geriatric screening (G8 tool) and GAs in older adults with HNC undergoing definitive RT or CRT demonstrate cumulative impairments in several gero-centric domains from baseline to 4 weeks into RT/CRT (61). Long-term objective trajectory data are needed to complement the 190largely patient-reported outcomes in the geriatric HNC literature. To start to address this knowledge gap, a group of trials evaluating older adults with HNC have commenced in France (62). These includes the “umbrella” trial, EGESOR (//clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02025062), which encompasses all patients aged 65 years or older with HNC undergoing treatment to evaluate a composite outcome of overall survival, weight loss, and loss of ADLs. Within the scope of this study, those aged 70 or over who were selected for definitive RT without chemotherapy will undergo either a hyporactionated course of RT versus standard RT based on GA determining whether they are “unfit” or “fit,” respectively, with locoregional control as the primary outcome (ELAN_RT: //clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01864850). In addition, those with metastatic/recurrent disease will be stratified, based on GA-determined fitness, either to triplet therapy (i.e., EXTREME regimen) (ELAN FIT: //clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01884623) or monotherapy (cetuximab or methotrexate) (ELAN UNFIT: //clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01884623). These studies will evaluate response rates along with toxicity and loss of ADLs as the primary outcomes. Combined-modality treatments (e.g., CRT) focused on older adults and/or functionally vulnerable patients will require further investigation, particularly with newer systemic agents and treatment paradigms (e.g., immunotherapy, response-adapted treatment) emerging.

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree