Chapter 26 Haematology in under-resourced laboratories

Introduction: types of laboratories

In under-resourced countries, these difficulties are compounded by the high burden of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. There are also additional pressures from external agencies for diagnostic and monitoring services which may not accurately reflect local public health priorities. Parasitological diagnosis of malaria is now recommended in all age groups to prevent the over-diagnosis and misuse of new anti-malarial combination drugs. Although it is currently the subject of much debate, WHO guidelines state that the only exception to the requirement for parasitological diagnosis is children aged under 5 years living in stable high-transmission settings where the likelihood of malaria as a cause for fever is high.1 Occasionally, in tertiary centres, the diagnosis of tuberculosis requires aspiration and culture of the bone marrow and trephine biopsy examination, especially in patients who are HIV positive, in whom sputum tests for acid-fast organisms are frequently negative.2 The decision to initiate antiretroviral therapy and the monitoring of therapy require regular haemoglobin concentration (Hb) estimations, CD4-positive lymphocyte counts (or percentages for paediatric care) and, ideally, plasma viral load determinations, although the maintenance of equipment for some of these tests is challenging for low-income countries.3,4

The purpose of this chapter is to provide guidance for an effective haematology service at the different levels of the healthcare system in resource-limited countries. In planning such services, it is necessary to determine what tests are needed at each level and to identify the relevant referral networks for clinical haematology. For example, successful management of haematological malignancies in countries with limited resources might involve partnerships between local institutions and those in more wealthy countries to adapt treatment protocols, to provide training or diagnostic services or to improve local supportive care facilities.5,6

Organization of clinical laboratory services

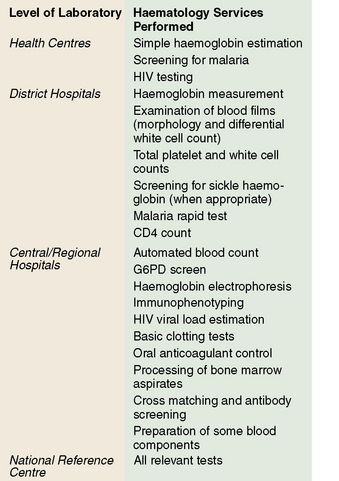

In under-resourced countries clinical laboratory services may be considered at three levels according to their size, staffing and services offered. These are levels: (A) subdistrict facilities including health centres; (B) district and referral hospitals; and (C) central reference and teaching hospitals (Fig. 26.1).

Availability of tests at each level

Level A

Level B

Level C

Microscopes

The microscope is the most important piece of laboratory equipment in under-resourced countries and is essential for the diagnosis of anaemia, malaria and other blood parasitic infections and for performing total and differential white blood cell counts. Reliable assessment of morphological features requires a microscope that is clean and correctly set up with aligned lenses and an electric light source (either inbuilt or reflected light) to ensure clear images, especially at high magnification. Failure to maintain microscopes to a high standard by routine user maintenance or, ideally, with regular professional servicing, can lead to inaccurate diagnoses and inefficient use of technician time.8,9 Routine maintenance of the microscope is described on p. 52.

‘Essential’ haematology tests

Despite the relatively high cost of running a laboratory service and the low per capita healthcare budget in under-resourced countries, there are few data available on which to base rational decisions about ‘essential’ laboratory tests.10,11 In many of these countries, decisions are made at central level by healthcare planners without adequate consultation with laboratory managers and experts. The selection of ‘essential’ tests at each level should be based on the clinical and public health needs of the local community and the availability of qualified clinical and laboratory staff, as well as on the availability of funds. Essential test packages are usually defined as part of national policy and standards, taking into consideration medium- and long-term trends and the requirements of disease control programmes.

To ensure cost-effectiveness of the laboratory service, tests with no proven value should be eliminated and new tests for which there is independent evidence of clinical usefulness should be introduced,12 as described in Chapter 24, p. 567. Tests that provide objective qualitative or quantitative information are preferred. Although it is not possible to draw up a list of essential tests that will be applicable to all countries, or even to different regions within a country, the following aspects should be considered.

Cost per Test

Often the cost of a test is calculated from the price of reagents divided by the number of tests performed. However, this oversimplifies the situation and is not accurate enough to form the basis for national policy decisions and budget allocation.11 The factors that need to be taken into account when calculating the total annual costs for a laboratory are given in Chapter 24.

Diagnostic Reliability

The quality of all tests carried out by a laboratory should be regularly monitored; systems for doing this are well-established (see Chapter 24) but are not easily implemented in under-resourced settings. The quality of a test influences its usefulness as well as its utilization by clinicians and community members. For example, if the result of a test in routine practice is correct only 80% of the time, then one in five tests will be wasted, reducing the effectiveness of the test by 20%. Furthermore, the inaccurate test may result in a patient receiving inappropriate treatment. Clinicians and the general public are increasingly aware of the need for accurate diagnosis. Clinicians may not order tests or use the results in patient management decisions if they do not trust the quality of the laboratory results13 and poor quality healthcare may deter patients from using health facilities.

Clinical Usefulness

An assessment of the clinical usefulness of a test should be carried out by an independent clinician who is familiar with local diseases and the diagnostic support services that are available. This assessor needs to compare actual clinical practice with locally agreed ‘best practice’ or, if available, local guidelines.12 From observation of a range of clinical interactions, the percentage of times that ideal practice is followed can be calculated. For example, transfusion guidelines may recommend that transfusions are given routinely to children with an Hb of <5 g/dl. The assessor can record how many children with Hb below this level failed to receive a transfusion and how many transfusions were given without waiting for the Hb result or at an inappropriate Hb level. For each test, the assessor needs to judge whether the test has been appropriately requested and is used to influence patient management or public health decisions. The percentage of tests that are not used to guide clinical decisions will provide a figure for ‘clinical wastage’ of the test that can be entered into the formula (Chapter 24).

Maintaining quality and reliability of tests

Paradoxically, it is in under-resourced laboratories, where equipment and supplies are limited and training and supervision may be minimal, that the level of skills and motivation required to maintain a good-quality service need to be highest. Even the most basic of laboratories should ensure that procedures are in place to monitor quality (see Chapter 25). In addition to monitoring the technical quality of each test, the quality of the whole service must be ensured both within the laboratory and between laboratories. Standard operating procedures (see p. 575) should be drafted for every method performed in the laboratory; these can be adapted from existing standard operating procedure ‘models’. In addition to providing standardized techniques, standard operating procedures are excellent teaching resources and adherence to these procedures will minimize errors. Standard operating procedures need to be regularly reviewed and updated to keep pace with technical developments and changes in local circumstances (e.g. non-availability of reagents, technical limitations).

Quality Control of a Test Method (Technical Quality)

Methods for the control of various haematology tests are described in Chapter 25 but some may need to be adapted to specific local circumstances in resource-poor countries. For example, if commercial controls are not affordable, each batch of sickle cell screening tests should include known positive and negative samples from a previous batch of tests; for monitoring constancy of Hb estimations, a high and a low value sample can be re-tested several times during the day.