(1)

State University of New York at Buffalo Kaleida Health, Buffalo, NY, USA

The inguinal nodes provide drainage of the lymphatic flow from the ipsilateral lower extremity, the lower abdominal wall, the perineum, the genitalia, and the buttock. A superficial groin dissection refers to the removal of the inguinal nodes from just above the inguinal ligament to the apex of the femoral triangle. A radical (ilioinguinal) dissection involves the removal, preferably in continuity, of the iliac and obturator nodes in addition to the inguinal nodes.

The procedure is performed with the patient in supine position and the thigh slightly abducted and externally rotated, often by placing a pillow under the knee joint. The skin of the lower abdomen, starting above the umbilicus and iliac crest all the way to the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the thigh is prepped with an antiseptic solution and surrounded with sterile drapes.

Incisions and Flaps

A variety of incisions have been employed. Some surgeons prefer the use of a transverse or nearly transverse incision, on the belief that by following the skin lines, a more cosmetic incision is likely to result. However, with the use of a transverse incision, which would extend from the anterior superior iliac spine (or just above it) to the pubic tubercle or below, the whole chain of inguinal nodes to the apex of the femoral triangle cannot be exposed and encompassed in the resection, so transverse incisions may not provide adequate exposure. The other problem of transverse incisions is that they seem more likely to cause lymphedema, because the subcutaneous lymphatics, which course in a vertical direction, would be more likely to be divided completely for the length of the incision, compared with a vertical incision, which is parallel to the course of the lymphatics. Although there has been no study to demonstrate that transverse incisions in the groin are more likely than vertical incisions to cause lymphedema, a “thought” experiment provides some credence to that statement. If one were to make a transverse incision extending circumferentially down to the level of the muscles around the mid thigh, a case of severe lymphedema is certain to follow, whereas a vertical incision of the same length, exposing the femoral vessels from the groin to the area of the knee (as in vascular operations requiring this exposure), is not likely to cause lymphedema.

Some surgeons have preferred to use a “lazy S” incision, starting with a nearly vertical segment laterally along the iliac crest, changing near the groin crease to a transverse or oblique component to the pubic tubercle, followed by a vertical component toward the apex of the femoral triangle. In the case of a recurrent tumor in the groin after a previous groin dissection, an ellipse must be made around the previous incision. Some authors have suggested the routine use of an elliptical incision over the course of the lymphatics and lymph nodes, aiming at using a skin graft at the end of the procedure over the mobilized sartorius, which is covering the femoral vessels. This practice avoids the construction of flaps, with the attendant risk of skin edge necrosis, while with careful construction of the flaps, necrosis is absent in the vast majority of patients. If present, it is minimal and usually restricted to a very narrow strip of about one-half centimeter from the skin edge. This superficial necrosis does not require postoperative débridement.

The incision that seems preferable in providing adequate exposure and minimizing the interruption of the lymphatics is slightly oblique, nearly vertical, starting about two fingerbreadths superomedial to the anterior superior iliac spine. It proceeds almost vertically to the middle of the inguinal ligament and then continues in the same direction to the apex of the femoral triangle (Fig. 40.1). The apex of the femoral triangle is the point where the sartorius crosses over the adductor longus.

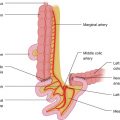

Fig. 40.1

A straight, nearly vertical incision beginning a few centimeters above the anterior superior iliac spine is carried over the middle of the inguinal ligament to the apex of the femoral triangle

The flaps are developed using an initial thickness of about 3–4 mm, becoming progressively thicker as the base of the flap is approached. If there is clinically palpable disease close to the skin, however, either thinner flaps are made initially or the skin is removed in continuity with the underlying lymph nodes, depending on the clinical situation. A somewhat thicker flap (about 0.5 cm), when feasible, may help preserve more subcutaneous lymphatics and therefore may reduce the incidence of lymphedema and the rate of skin-edge necrosis. Furthermore, the flap need not be made equally thick throughout its length. It should be thin at its middle, over the anatomic position of the group of lymph nodes, and thicker toward the ends of the flap, where no lymph nodes are likely to be present or involved. One also should avoid making the flaps wider than the recognized boundaries.

Initially, the medial flap is developed to the pubic tubercle and the adjacent external oblique aponeurosis superiorly, and to the medial edge of the adductor longus or the adjacent anterior edge of the gracilis inferiorly. Above the pubic tubercle, the dissection is continued down to the surface of the external oblique. In this area, the subcutaneous fat and any lymph nodes are mobilized toward the inguinal ligament. Scalpel dissection is preferable to using the cautery because it is more precise and less likely to cause incidental small openings in the external oblique fascia. The subcutaneous fat also is cleared off the spermatic cord or round ligament, in an inferior direction. The anterior border of the gracilis muscle is exposed and the fascia is incised and dissected off the surface of the adductor longus (Fig. 40.2). As the subcutaneous fat is traversed in the lower part of the flap, the great saphenous vein is encountered and is ligated and divided. With the proper tension in the tissues and the use of a sharp blade, all structures over 2 mm in diameter should be exposed, visualized, and controlled before their actual division. The fascia lata on the adductor longus and the pectineus is dissected off these muscles until the medial side of the femoral vein is exposed and its sheath is entered (Fig. 40.3). As the dissection continues on top of the superficial femoral vein, one visualizes the profunda femoris vein connected to the posterior surface of the femoral vein, and anteriorly one encounters the great saphenous vein at the point of its entry in the femoral vein deep to the foramen ovalis (Fig. 40.4); it is ligated and divided. The stump of the great saphenous vein on the femoral vein is secured with a suture ligature, in addition to a tie. A horizontal mattress suture is placed at the base of the stump of the great saphenous vein on the side of the specimen because only a short stump is available deep to the foramen ovalis, and if it is not ligated with a suture ligature, the tie may come off and cause temporary bleeding. The superficial femoral artery is exposed; its sheath is entered and dissected off the artery (Fig. 40.5). The lateral flap is also developed. Obviously, the order of the development of these flaps can be reversed, the lateral flap being done first, followed by the development of the medial flap. The lateral flap is also developed with 3–4 mm thickness of subcutaneous fat initially, provided there are no clinically suspicious lymph nodes in the adjacent tissues (in which case it is made thinner). For fine dissection, the flap is kept under tension provided by the use of Adair clamps on the edge of the flap and countertraction over a lap pad at the developing base of the flap by the nondominant hand of the surgeon. The flap is developed using sharp dissection with light cautery or a scalpel, the latter being more precise, particularly when one works over the femoral vessels. As the lateral border of the sartorius is encountered, the fascia is incised and dissected off the surface of this muscle. At about 3 cm below the anterior superior iliac spine, the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is visualized as it courses obliquely over the sartorius muscle near its origin. After crossing in front of the sartorius in an inferolateral direction, this nerve divides into branches providing sensory supply to the lateral aspect of the thigh. With a little care, this small sensory branch can be preserved (Fig. 40.6). As the fascia over the sartorius muscle is mobilized, one reaches an area of loose areolar tissue, which is dissected, visualizing branches of the femoral nerve, most of which are sensory to the anteromedial thigh (recognizable as such by their course toward the skin, or by a nerve stimulator). These branches are divided. There are one or two motor branches to the sartorius, and a single motor branch to the vastus medialis, which follows a straight downward course along the surface of the vastus medialis. This nerve and the saphenous nerve, a terminal branch of the femoral nerve that runs along the femoral artery and is sensory to the anteromedial leg, are both more posteriorly located and therefore are not encountered in a routine dissection. The branches to the rest of the quadriceps, crossing under the proximal part of the rectus femoris in an inferolateral direction, should definitely be preserved, as they are outside the operative field of the proper groin dissection. As the femoral artery is approached, dissection within the sheath covering this vessel is continued on the lateral aspect of the artery, and thus the sheath is dissected off the surface of the artery, ligating and dividing small branches of the superficial femoral artery. The fields then provided by the medial and lateral flap development are united over the surface of the superficial femoral vessels. As the dissection continues on the artery, superiorly the profunda femoris artery can be visualized, along with the lateral femoral circumflex branch, which provides the main blood supply to the quadriceps. The dissected tissue is then mobilized toward the femoral canal area. If only a superficial groin dissection is planned, the lymph nodes in the femoral canal are mobilized and the specimen is amputated at the femoral ring, including Cloquet’s node for its possible prognostic information on the positivity of the deep nodes. This node situated at the femoral ring, if negative on biopsy, indicates that the deep nodes are likely negative, whereas if positive it indicates that the deep nodes are likely positive also [1].

Fig. 40.2

The medial flap has been developed, exposing superiorly the external oblique aponeurosis; in the middle, the pubic tubercle, the spermatic cord, or the round ligament; and inferiorly, the medial edge of the adductor longus

Fig. 40.3

The medial flap is further developed, exposing the edge of the gracilis. As the fascia lata is mobilized with the specimen, the adductor longus, the pectineus, and the anteromedial aspect of the femoral vein are evident. The great saphenous vein has been divided distally

Fig. 40.4

The femoral vein (superficial and common) has been exposed and dissected, to the entry of the great saphenous vein into the femoral vein

Fig. 40.5

The anterior aspect of the superficial femoral artery has been exposed

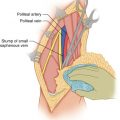

Fig. 40.6

The lateral flap has been developed, exposing superiorly the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and the anterior surface of the sartorius muscle

Ilioinguinal Dissection

Superficial groin dissection is generally performed for patients who have microscopic involvement of a lymph node, such as a sentinel node or minimal clinical involvement of an inguinal node, with negative findings for the higher nodes, particularly in the femoral canal, including Cloquet’s node. For patients who have larger lymph nodes in the groin and evidence of enlarged lymph nodes by preoperative CT scan in the area of the deep nodes or a positive Cloquet’s node, ilioinguinal dissection is indicated in order to remove the superficial inguinal nodes and the external iliac and obturator nodes, preferably in continuity. To do so, the specimen of the superficial groin dissection is left attached to the femoral canal lymphatic tissue and nodes so that it can be removed in continuity with the deep nodes. The proposed incision in the external oblique aponeurosis is then outlined, by making short cuts along the imaginary line starting 6–8 cm superomedial to the anterior superior iliac spine and proceeding obliquely toward the inguinal ligament about 2 cm lateral to the femoral artery (Fig. 40.7). The dissection of the lymph nodes of the superficial groin is about to be completed as the nodes and lymphatic channels aggregate in the femoral canal, their narrow passage of communication with the deep nodes (Fig. 40.8). If the decision is to perform a superficial groin dissection, the lymphatic tissue from the femoral canal is mobilized inferiorly, marked with a stitch for the pathologist, and the specimen removed. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised now completely down to the inguinal ligament. The inguinal ligament is divided, and then the internal oblique and transverse abdominis are divided superiorly, entering the retroperitoneal space. The peritoneum is displaced superomedially using blunt dissection, and then the inguinal ligament is divided completely. One should be careful, however, as the deep iliac circumflex vessels course in a fold of the iliac fascia posterior to the inguinal ligament. The deep iliac circumflex vessels arising from the lateral aspect of the external iliac vessels proceed behind the inguinal ligament toward the iliac crest. These vessels may be divided, if necessary. As the medial portion of the inguinal ligament is lifted, one encounters the inferior epigastric artery (Fig. 40.9), originating from the terminal part of the external iliac artery, which is doubly ligated and divided. Medial and adjacent to this artery is found the inferior epigastric vein, which is also doubly ligated and divided. The dissection continues on top of the external iliac artery to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, mobilizing the lymph nodes by entering the sheath of the external iliac artery and the external iliac vein. The lymph nodes are separated superiorly from the external iliac vessels. Anteriorly they must be separated from the peritoneum and transversalis fascia. As the dissection is continued superiorly, the bifurcation of the common iliac artery is exposed, and any lymph nodes over the internal iliac artery are dissected (Fig. 40.10). Over the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, the ureter is visualized and displaced superiorly. The urinary bladder is separated from the obturator nodes. Dissecting through the loose areolar tissue, one encounters the inferior epigastric artery and vein again as they are about to go behind the rectus abdominis. They are ligated and divided. In this procedure, therefore, one removes a 4–5 cm segment of the inferior epigastric vessels as they course from their origin from the external iliac vessels to behind the rectus abdominis. This portion of the inferior epigastric vessels courses close to the deep lymph nodes mobilized from the pelvic wall. A few centimeters cephalad to the inferior epigastric vein is a fairly constant tributary of the external iliac vein, the pubic vein, which needs to ligated and divided.