Glandular Lesions

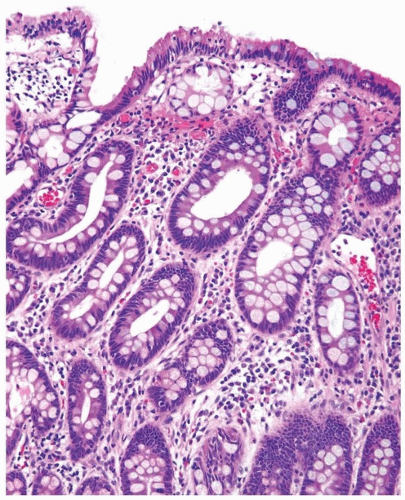

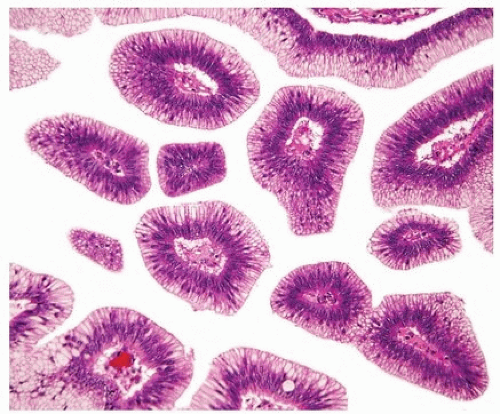

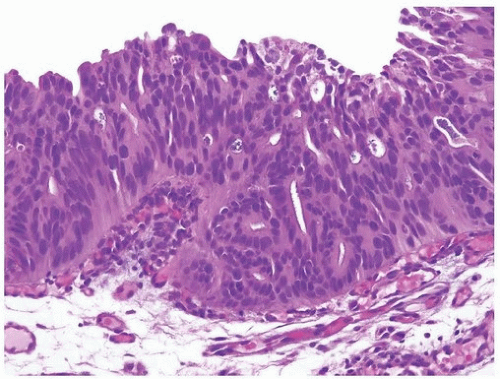

CYSTITIS GLANDULARIS (INTESTINAL TYPE)

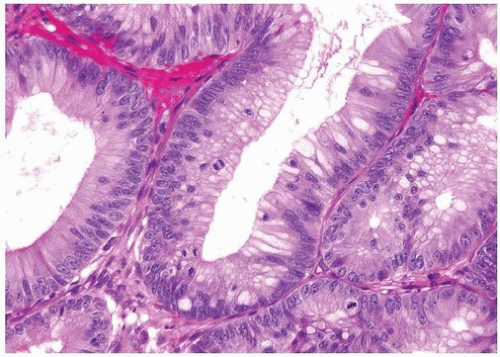

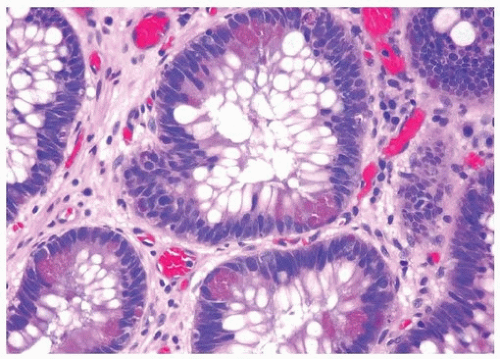

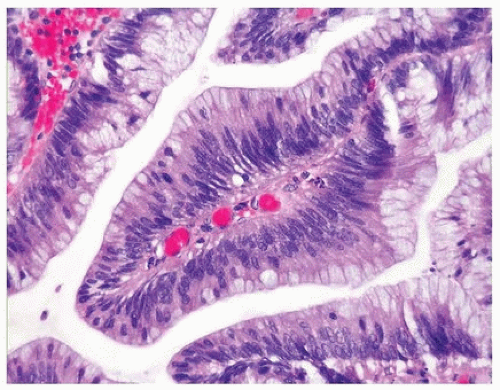

In some cases, the epithelial lining of Brunn nests and cystitis cystica undergo glandular metaplasia, giving rise to what is called cystitis glandularis (1, 2). The cells become cuboidal or columnar and mucin secreting, taking on the appearance of intestinal-type goblet cells. This variant is called cystitis glandularis with intestinal metaplasia (Figs. 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4) (efigs 8.1-8.19). The change may be focal or may diffusely replace the lining urothelium, both presenting as flat or minimally elevated or otherwise distorted mucosa. Some cases of intestinal metaplasia may be associated with abundant mucin extravasation and may present as symptomatic mass lesions. Although there is overlap between some examples of intestinal metaplasia and well-differentiated adenocarcinoma in some of the histological features (dissecting mucin, infiltration of muscularis propria, reactive atypia, and mitoses), the degree and extent of these findings differ between the two conditions (3, 4). In contrast to the extensive mucinous pools seen in some adenocarcinomas, florid intestinal metaplasia has only focal areas of mucin extravasation and is devoid of neoplastic cells within mucin pools. Whereas adenocarcinomas typically show extensive and deep muscularis propria invasion, intestinal metaplasia is usually confined to the lamina propria and muscularis propria involvement if present is typically limited and superficial (Fig. 8.5). Although rare bladder adenocarcinomas may show bland cytology, which in our experience often represent metastases from the pancreas, most will have areas of the tumor with overt cytological atypia. The atypia seen in intestinal metaplasia is negligible, and mitoses, although frequent in adenocarcinoma, are found only rarely in intestinal metaplasia. The cells lining the colonic-type glands are cytologically bland, while those seen in bladder adenocarcinoma are more akin to what is seen in intestinal-type or mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon. Other less well-differentiated cases of adenocarcinoma may contain signet cells embedded in mucin and necrosis, findings that are not found in intestinal metaplasia. Long-term follow-up of cases of intestinal metaplasia has confirmed a benign behavior (5). Exceptionally, isolated glands of intestinal metaplasia may show moderate dysplasia, in an analogous fashion to those

seen in a colonic adenoma; the significance of this finding is unknown, although close follow-up is warranted (Fig. 8.6) (6). In this setting, if the lesion is extensive on the initial transurethral resection, it may be prudent to suggest that the area be re-resected.

seen in a colonic adenoma; the significance of this finding is unknown, although close follow-up is warranted (Fig. 8.6) (6). In this setting, if the lesion is extensive on the initial transurethral resection, it may be prudent to suggest that the area be re-resected.

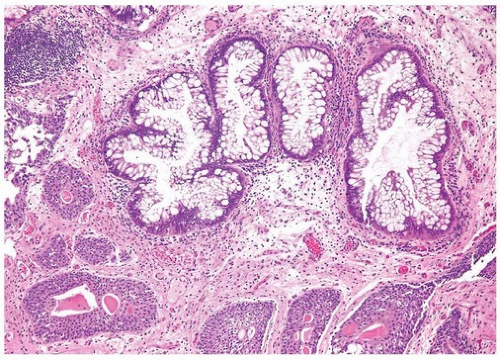

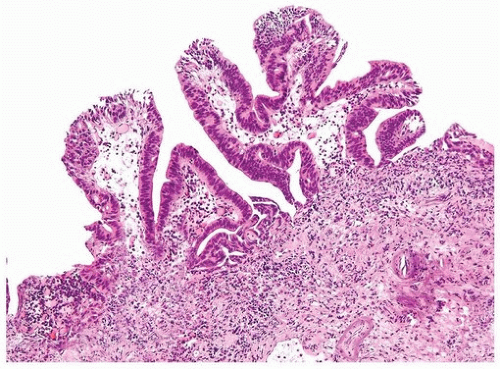

FIGURE 8.3 Cystitis glandularis, intestinal type. Note nonintestinal type cystitis cystica and glandularis (bottom). |

Glandular metaplasia may also occur within surface urothelium, usually as a response to chronic inflammation or irritation, such as in cases of bladder exstrophy (7, 8). The epithelium is composed of tall columnar cells with mucin-secreting goblet cells, strikingly similar to benign colonic or small intestinal epithelium in which one might identify even Paneth cells.

FIGURE 8.5 Cystitis glandularis, intestinal type with extracellular mucinous pools dissecting muscularis propria. |

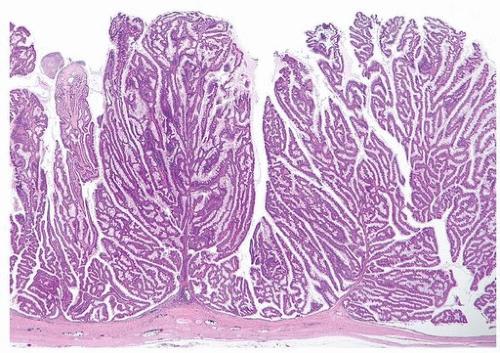

VILLOUS ADENOMA

The way to conceptualize glandular lesions occurring in the bladder and urethra is that they are analogous to glandular lesions seen in the intestinal tract both in term of types of lesion and their morphology. The full spectrum of lesions may be seen in the bladder and urethra including villous adenoma, villous adenoma with in situ adenocarcinoma, villous adenoma with infiltrating adenocarcinoma, and infiltrating adenocarcinoma unassociated with villous adenoma. Villous adenomas and adenocarcinomas in the bladder occur in one of two general locations. They may arise within the urachus such that they are seen at the dome or anterior wall of the bladder, where they may present as a painful suprapubic mass. The other setting in which glandular lesions arise in the bladder is from a process of neometaplasia in which they may occur anywhere in the bladder, typically near the trigone.

For both villous adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the bladder, there is a male predominance. Patients with villous adenoma or adenocarcinoma may either present with nonspecific findings or occasionally present with mucosuria. If the lesion is pure villous adenoma with or without in situ adenocarcinoma and the lesion is entirely resected, then the prognosis is excellent (9, 10, 11, 12, 13). However, if the lesion has been only subtotally removed especially in the setting of coexistent in situ adenocarcinoma, the tumors have the potential to progress to infiltrating adenocarcinoma. As infiltrating adenocarcinoma is frequently present with villous adenoma, it necessitates thorough sampling of any lesion diagnosed by biopsy as villous adenoma. The diagnosis of villous adenoma should be reserved for cases in which the villous projections are lined by intestinal-type epithelium, which exhibits typical adenomatous features (Figs. 8.7, 8.8, 8.9, 8.10, 8.11) (efigs 8.20-8.36). Nuclei may be enlarged and multilayered with abundant apically located cytoplasm.

Mitoses are unapparent or few and regular. Cytologic and architectural features of intramucosal carcinoma are absent. Caution is warranted in making a diagnosis of villous adenoma in a small biopsy sample as a surface villous histology may be seen in villous adenoma as well as villous adenoma associated with adenocarcinoma in which the latter is not sampled. Colonic/rectal adenocarcinomas can invade the bladder mimicking a primary villous adenoma of the bladder, especially on limited biopsy material. Therefore, it is prudent to include a comment in the pathology report that while the lesion is probably a primary villous adenoma of the bladder, spread from an intestinal neoplasm should be clinically excluded.

In addition to in situ or invasive adenocarcinoma, urinary tract villous adenomas have been found in association with squamous cell carcinoma, flat in situ urothelial carcinoma, noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma, infiltrating urothelial carcinoma, and sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Associated urothelial carcinoma elements are not always discrete from villous adenomas but often merge imperceptibly with them. These findings indicate that glandular lesions of the urothelium, whether benign or malignant, arise through a process of metaplasia/neometaplasia and are a manifestation of the morphologic plasticity of the urothelium.

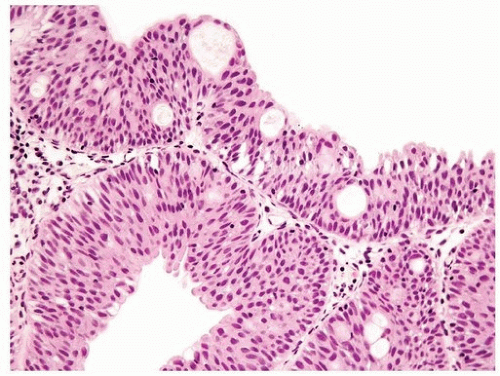

NONINVASIVE UROTHELIAL CARCINOMA WITH GLANDULAR DIFFERENTIATION

Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinomas may have gland-like lumina, a common finding that should not be confused with adenocarcinoma (Figs. 8.12, 8.13). In other cases, the noninvasive component, whether flat or papillary, may exhibit unequivocal glandular features (Figs. 8.14, 8.15, 8.16, 8.17, 8.18) (efigs 8.37-8.54). Chan and Epstein described a series of 19 cases of noninvasive urothelial carcinomas with glandular differentiation (referred to

as “in situ adenocarcinoma”) of the bladder unaccompanied by infiltrating adenocarcinoma (14). Noninvasive urothelial carcinomas with glandular differentiation had a high incidence of association with CIS and specific subtypes of prognostically poor invasive carcinomas, such as small cell and micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. In a more recent larger study from the same group, the noninvasive glandular component consisted of one or more patterns, including papillary, glandular, cribriform, and flat. Half of the cases were associated with “usual” urothelial CIS or high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Of those cases that subsequently progressed to invasion, none did so as adenocarcinoma but rather as small cell carcinoma

or poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma (15). These data confirm that this disease is a morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma in situ and that divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma, whether invasive or not, is usually associated with aggressive clinical behavior. The only situation where the term “adenocarcinoma in situ” is used is when associated with intestinal metaplasia or a villous adenoma. Otherwise, precursor glandular lesions with atypia should be referred to as either noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma or CIS with glandular differentiation.

as “in situ adenocarcinoma”) of the bladder unaccompanied by infiltrating adenocarcinoma (14). Noninvasive urothelial carcinomas with glandular differentiation had a high incidence of association with CIS and specific subtypes of prognostically poor invasive carcinomas, such as small cell and micropapillary urothelial carcinoma. In a more recent larger study from the same group, the noninvasive glandular component consisted of one or more patterns, including papillary, glandular, cribriform, and flat. Half of the cases were associated with “usual” urothelial CIS or high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Of those cases that subsequently progressed to invasion, none did so as adenocarcinoma but rather as small cell carcinoma

or poorly differentiated urothelial carcinoma (15). These data confirm that this disease is a morphologic variant of urothelial carcinoma in situ and that divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma, whether invasive or not, is usually associated with aggressive clinical behavior. The only situation where the term “adenocarcinoma in situ” is used is when associated with intestinal metaplasia or a villous adenoma. Otherwise, precursor glandular lesions with atypia should be referred to as either noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma or CIS with glandular differentiation.

FIGURE 8.13 Noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma with gland-like lumina (higher magnification [right]). |

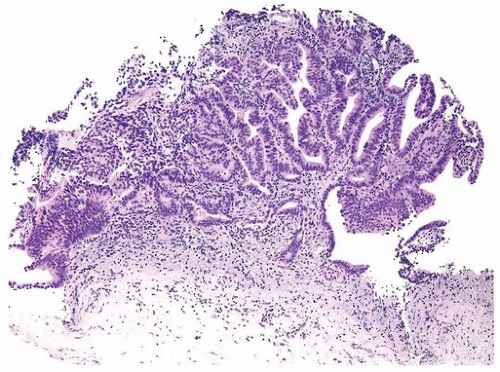

FIGURE 8.15 Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation, papillary pattern composed of simple and branching fronds. |

FIGURE 8.16 Higher magnification of Figure 8.15 shows glandular differentiation with columnar nuclei and apical cytoplasm. The nuclei still retain some of the features of CIS cells (i.e., hyperchromatic enlarged cells without prominent nucleoli). |

FIGURE 8.17 Noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation, complex papillary pattern. |

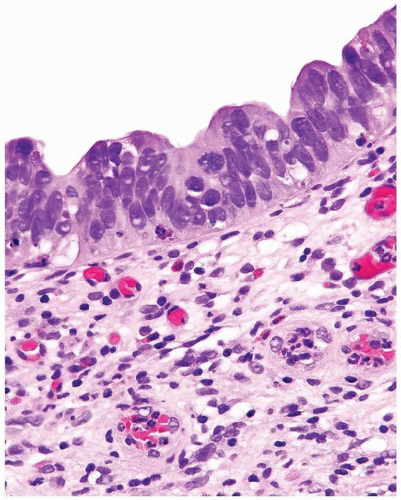

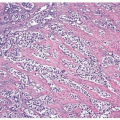

INFILTRATING ADENOCARCINOMA

Primary pure adenocarcinomas of the bladder are rare, representing no more than 2.5% of all malignant vesical neoplasms. By definition, the tumor should be composed entirely, or virtually entirely, of glandular elements. With the exception of the extremely rare examples of adenocarcinomas that arise from müllerian or mesonephric remnants located within the wall of the urinary bladder, they arise through a process of divergent differentiation in urothelial carcinoma (16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22). They constitute up to 90% of carcinomas associated with bladder exstrophy. The tumor is also more frequently encountered in a setting of schistosomiasis. Shaaban et al. (23) and El-Mekresh et al. (24) reported series of 93 and 185 cases, respectively, of vesical adenocarcinoma arising in this setting. Adenocarcinomas can arise anywhere on the bladder surface, although a large percentage originates from the trigone and posterior wall. A major clinical difference as compared to usual urothelial carcinomas is that two thirds of adenocarcinomas are single discrete lesions, while “usual” urothelial carcinoma tend to be multifocal (25, 26). Grossly, the tumors can be papillary, nodular, or flat and ulcerated. Microscopically, the tumor is most often composed of colonic-type glandular epithelium (enteric morphology) and often contains abundant extracellular mucin (Figs. 8.19, 8.20, 8.21) (efigs 8.55-8.68). However, some tumors are very cellular, cytologically less well differentiated, and do not contain extracellular mucin. We have seen rare examples with hepatoid or even yolk sac differentiation, the latter associated with serum elevation of alpha-fetoprotein. Regardless of the histologic pattern, cystitis cystica et glandularis or surface glandular metaplasia is commonly present in the adjacent benign urothelium. Rarely, they may be associated with villous adenoma of the bladder. Most adenocarcinomas have infiltrated

deeply at the time of initial diagnosis and are associated with a poor prognosis. Recent data suggest that, in its pure form, adenocarcinoma arising in the bladder has a worse prognosis than usual urothelial carcinoma even after adjusting for pathologic stage, lymph node status, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (27). Whether this finding is due to the fact that adenocarcinoma differentiation is resistant to systemic therapies directed at usual urothelial carcinoma remains to be proven. However, what has been well established is that tumors with mixed histologic features that include glandular differentiation have similar clinical outcome that pure urothelial carcinoma, when stratified by pathologic stage (28, 29, 30).

deeply at the time of initial diagnosis and are associated with a poor prognosis. Recent data suggest that, in its pure form, adenocarcinoma arising in the bladder has a worse prognosis than usual urothelial carcinoma even after adjusting for pathologic stage, lymph node status, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion (27). Whether this finding is due to the fact that adenocarcinoma differentiation is resistant to systemic therapies directed at usual urothelial carcinoma remains to be proven. However, what has been well established is that tumors with mixed histologic features that include glandular differentiation have similar clinical outcome that pure urothelial carcinoma, when stratified by pathologic stage (28, 29, 30).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree