Genital Mycoplasmas

The mycoplasmas are a unique group of microorganisms that commonly inhabit the mucosa of the respiratory and genital tracts. These include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, the agent responsible for atypical pneumonias, and genital mycoplasmas, commonly Mycoplasma hominis, Ureaplasma urealyticum (formerly T-mycoplasma or T strains), and Mycoplasma genitalium. Mycoplasma hominis and U. urealyticum are commonly found in the lower genital tract of women, whereas M. genitalium is detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in approximately 1% of women. The role for these ubiquitous genital microbes in reproductive disorders is the subject of ongoing debate. Phylogenetically, mycoplasmas fall between bacteria and viruses. All mycoplasmas have several characteristics in common, as shown in Table 2.1. They differ from bacteria because they have no cell wall; rather, a nonrigid, triple-layered membrane encloses the cell. Mycoplasmas are the smallest known free-living organisms. They differ from viruses because they contain both DNA and RNA and because they can grow in cell-free media.

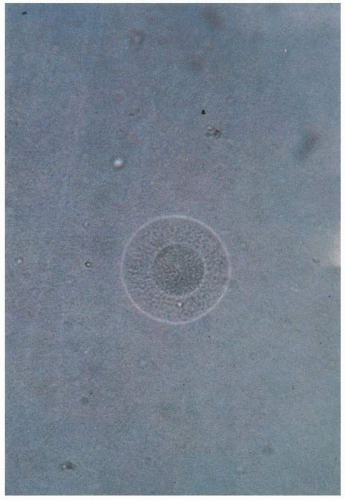

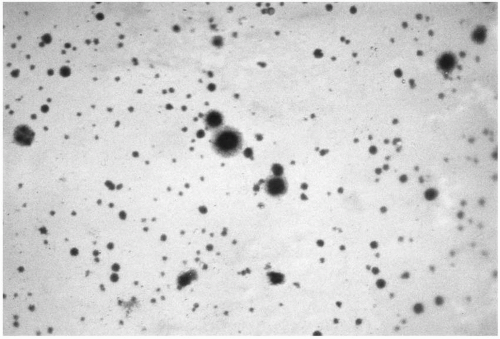

Mycoplasma hominis is distinguished from U. urealyticum by differences in colonial morphology, metabolic characteristics, and susceptibility to antibiotics (Table 2.2). Mycoplasma hominis, an aerobic organism, is recognizable as a “fried egg” colony (Fig. 2.1). The organism converts arginine to ornithine with the liberation of ammonia. This reaction produces a color change when an appropriate pH indicator is incorporated into broth media containing arginine. Ureaplasma urealyticum is a microaerophilic organism characterized by small colony size and its ability to hydrolyze urea (Fig. 2.2). Urea is an essential substrate for growth and is converted to ammonia. This reaction can be detected by a color change of a pH indicator in broth or agar containing urea.

Mycoplasma genitalium was identified in the early 1980s, initially from men with nongonococcal urethritis. Further evidence has strengthened the association between M. genitalium and nongonococcal urethritis. The role of M. genitalium has been clarified by the development of DNA amplification assays. The prevalence of M. genitalium (as detected by PCR) was 1.0% of urine specimens from a sample of approximately 3,000 young adults in the United States (1.1% in males and 0.8% in females). Overall, M. genitalium was more common than gonorrhea (0.4% prevalence) but less common than Chlamydia trachomatis (4.2%) and Trichomonas vaginitis (2.3%).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Infants become colonized with genital mycoplasmas during birth. The organisms are acquired from a colonized cervix or vagina. Approximately one third to one half of newborn girls have vaginal colonization with U. urealyticum, and a smaller percentage harbor M. hominis. Vertical transmission of U. ureaplasma ranges widely, from approximately 20% to 50% for term infants and from 30% to 50% for preterm infants.

Genital mycoplasmas are uncommon in prepubertal girls. After puberty, colonization with genital mycoplasmas occurs primarily through sexual contact. A wide range in the recovery rate has been reported for U. urealyticum (40% to 95%) and for M. hominis (15% to 70%) among sexually active women. As noted, M. genitalium is detected less commonly.

Genital mycoplasmas are commonly isolated from gravid women at approximately the same recovery rate as in nonpregnant women with the same degree of sexual activity. In a large study of the epidemiology of U. urealyticum in midpregnancy, positive cultures of the lower genital tract correlated with black race, number of sexual partners, low income, younger age, and never being married. Isolation of U. urealyticum in the vagina at midpregnancy was also highly associated with bacterial vaginosis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, M. hominis, anaerobes, and T. vaginalis. The overall culture positivity was approximately 70%.

DIAGNOSIS

In the past, the diagnosis of mycoplasma infection has been based on isolation of the organism from a site of infection or demonstration of a rise in antibody titer. The role of mycoplasmas in disease has been facilitated by PCR. This is particularly true for M. genitalium, which is difficult to culture and grows very slowly. Special advantages of PCR include high sensitivity, rapid detection (within 24 hours), and faster subtyping. However, convincing evidence of infection caused by genital mycoplasmas is often difficult to establish. Only rarely are these organisms isolated by themselves; culture, serologic PCR, and techniques are not widely available to the clinician. In women, vaginal specimens are more likely to contain mycoplasmas than are specimens obtained from other sites in the lower genital tract. For optimal isolation of mycoplasmas by culture, specimens should be inoculated immediately into medium, kept at 4°C, and transported to the laboratory as soon as possible.

The basic medium for culture is available commercially and contains a nutritive broth, to which antibacterial agents are added to inhibit bacterial growth. The metabolic activity of mycoplasmas is used to detect their growth in broth medium. When M. hominis metabolizes arginine to ammonia, or when ureaplasmas break down urea to form ammonia, there is a resulting elevation of the pH that induces a color change in the broth. Aliquots of the medium from urea broth cultures are subcultured onto agar medium for positive identification in 1 to 4 days.

TABLE 2.1 ▪ GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF GENITAL MYCOPLASMAS | |

|---|---|

|

Few clinical laboratories provide cultures for genital mycoplasmas; however, there are few if any clinical circumstances when a culture for genital mycoplasmas is clearly indicated.

Various serologic procedures, including agglutination, complement fixation, indirect hemagglutination, metabolic inhibition test, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, have been used to detect serologic response to genital mycoplasmas. Although these are useful in research settings to determine the role of genital mycoplasmas in disease, the serologic tests have little to no utility in clinical practice. PCR techniques for detection of U. urealyticum and M. genitalium have been developed, and PCR techniques have been exploited to determine the role of mycoplasmas in genital tract infection.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF GENITAL MYCOPLASMA INFECTION

A summary of the role of genital mycoplasmas in obstetric-gynecologic conditions is given in Table 2.3.

Spontaneous Abortion and Stillbirth

Mycoplasmas, both ureaplasmas and M. hominis, have been associated with spontaneous abortion since the 1960s. Investigators reported the isolation of genital mycoplasmas from the chorion, amnion, and/or decidua of spontaneously aborted fetuses. However, a causal relationship has not been established because of contamination, because the products of conception pass through the cervix and vagina. Overall, these studies suggest that there is an association between spontaneous abortion and maternal or fetal infection, or both, due to genital mycoplasmas. However, it is not clear whether the relationship is causal because of the difficulty in comparing the study groups. Furthermore, the role of other microorganisms was not investigated. Studies limited to detection of genital mycoplasmas from the lower tract have been inconclusive.

TABLE 2.2 ▪ SPECIFIC CHARACTERISTICS OF MYCOPLASMA HOMINIS AND UREAPLASMA UREALYTICUM | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 2.2 Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum on a selective agar plate. Mycoplasma hominis appears as the larger “fried egg” colonies. |

Mycoplasmas have been isolated from the lungs, brain, heart, and viscera of stillbirths. However, none of these observations provides an answer to the question of whether stillbirth occurs because mycoplasmas invade the fetus and cause its death or because the fetus dies of another cause, with subsequent invasion of necrotic tissue by the mycoplasmas.

Because mycoplasmas are sensitive to antibiotics, it is possible that fetal loss, if caused by these organisms, could be prevented by appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Findings of older antibiotic studies purported to show a decrease in the rate of recurrent abortion by use of doxycycline or erythromycin. However, these studies did not assess other microorganisms (especially C. trachomatis and anaerobes) that are susceptible to the antibiotic regimens, and the antibiotic trials have not been appropriately controlled.

TABLE 2.3 ▪ SUMMARY OF THE ROLE OF GENITAL MYCOPLASMAS IN OBSTETRIC-GYNECOLOGIC CONDITIONSa

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|