375

Functional Dependency

Siri Rostoft and Benedicte Rønning

INTRODUCTION

Functional dependency is a geriatric syndrome where a person is not able to live independently and perform basic activities of daily living (ADLs). In older cancer patients, there are several reasons to evaluate functional status. First, functional status declines with aging, as all organ functions deteriorate with increasing age. As functional status provides an integrated picture of the person, it may be an overall indicator of a person’s health—determined both by age-related changes and by comorbidities. Second, being able to live independently seems to be more important than survival for older patients with severe illness (1), making functional status an important outcome. Third, functional status is frequently underrated and underreported by medical doctors (2). Even though it has been shown that functional status is an important predictor of 1-year mortality in older hospitalized patients (3), it is seldom reported in the admission evaluation. In a large cohort of several thousand older surgical patients, ADL impairment was a consistent independent predictor of postoperative mortality (4). Nevertheless, surgical publications rarely report preoperative functional status. In addition, gait speed, which is an objective physical performance measure of functional status, is highly correlated with mortality (5). In a recent Delphi study on geriatric assessment in oncology, functional status was rated the most important domain to consider in older cancer patients (6).

DEFINITION

Functional dependency is usually defined as needing help in one of the basic ADLs such as bathing, dressing, using the toilet, eating, or rising from a chair. When a patient is functionally dependent, he or she cannot live without assistance. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) describe more advanced activities necessary to live a fully independent life, like shopping, cooking, paying bills, and transportation. Of note, readers may come across a variety of definitions of functional dependency both in clinical practice and in scientific publications. It is important to emphasize that functional dependency may be the result of cognitive impairment. In fact, being functionally dependent is one of the diagnostic criteria for the syndrome of dementia. Thus, a complete evaluation of a patient’s functional status should include an assessment of cognitive function in addition to an assessment of physical function.

38DEVELOPMENT OF FUNCTIONAL DEPENDENCY

Functional dependency is considered a geriatric syndrome. It is usually caused by more than one single factor; it may develop slowly and may be the end result of chronic diseases and aging causing multiple impairments in an older person. However, functional dependency may also present more acutely in the setting of an acute medical illness or after cancer treatment such as extensive surgery or chemotherapy/radiation therapy. When the patient is vulnerable and has functional limitations before an acute illness or cancer treatment is initiated, the likelihood of developing functional dependency increases.

PREVALENCE

The prevalence of functional dependency in older patients varies considerably depending on the population assessed. In the nursing home population, the majority of patients are functionally dependent. In comparison, in the general population, data from Sweden show that about 75% of people at the age of 80 are functionally independent, and disability becomes common only after the age of 90 (7).

ASSESSMENT OF FUNCTIONAL STATUS

Information about functional status may be retrieved through a general clinical impression. Is the patient alert and orientated? Does she walk unaided to the consultation? Is she effortless in removing outerwear and sitting down? While such observations are helpful, the use of assessment tools provides more details, establishes a baseline, makes it easier to follow changes over time, and is helpful when communicating and documenting findings.

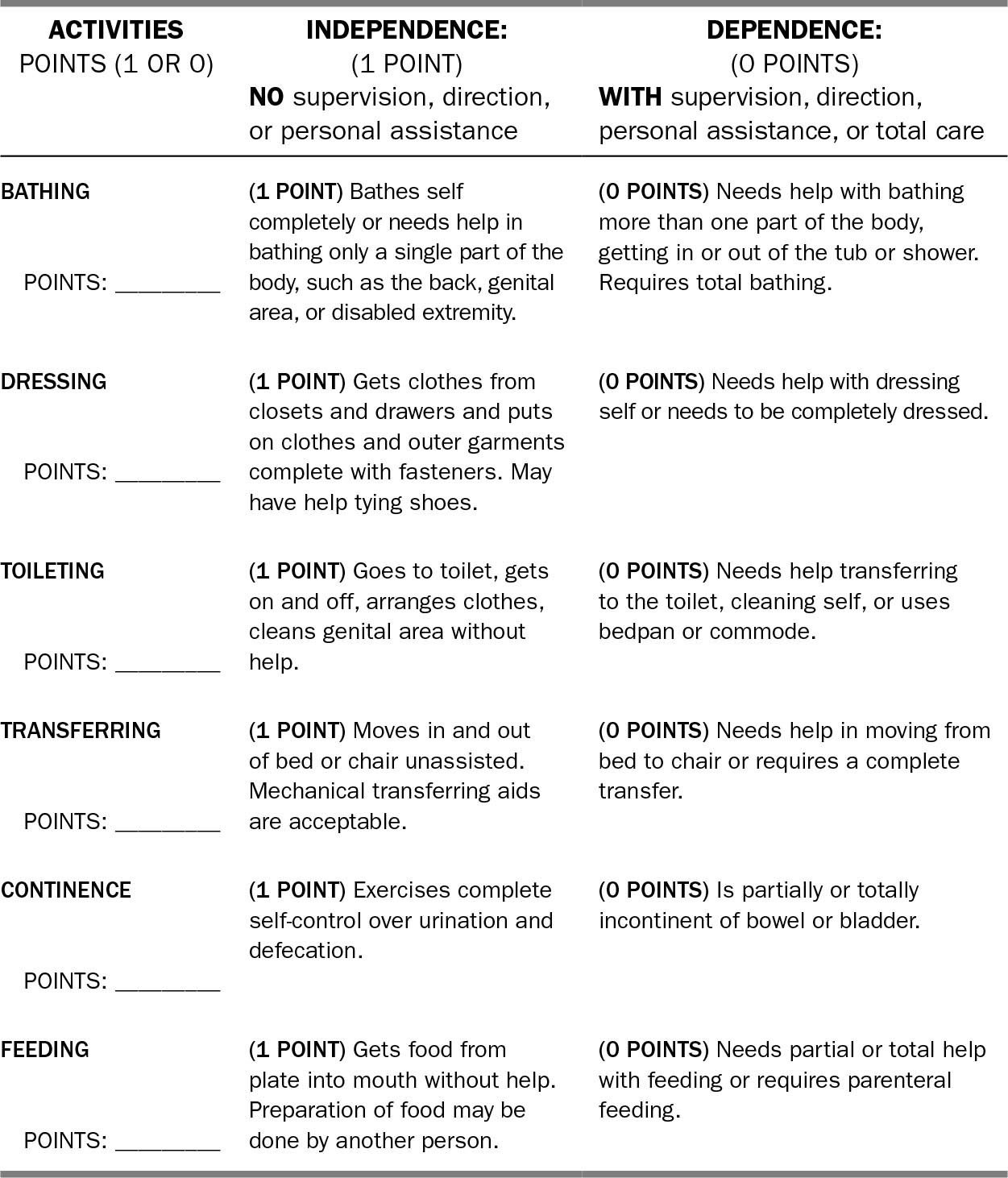

ACTIVITIES OF DAILY LIVING

1. Basic ADLs

-The Katz index (8) (Figure 5.1)

-The Barthel index (9)

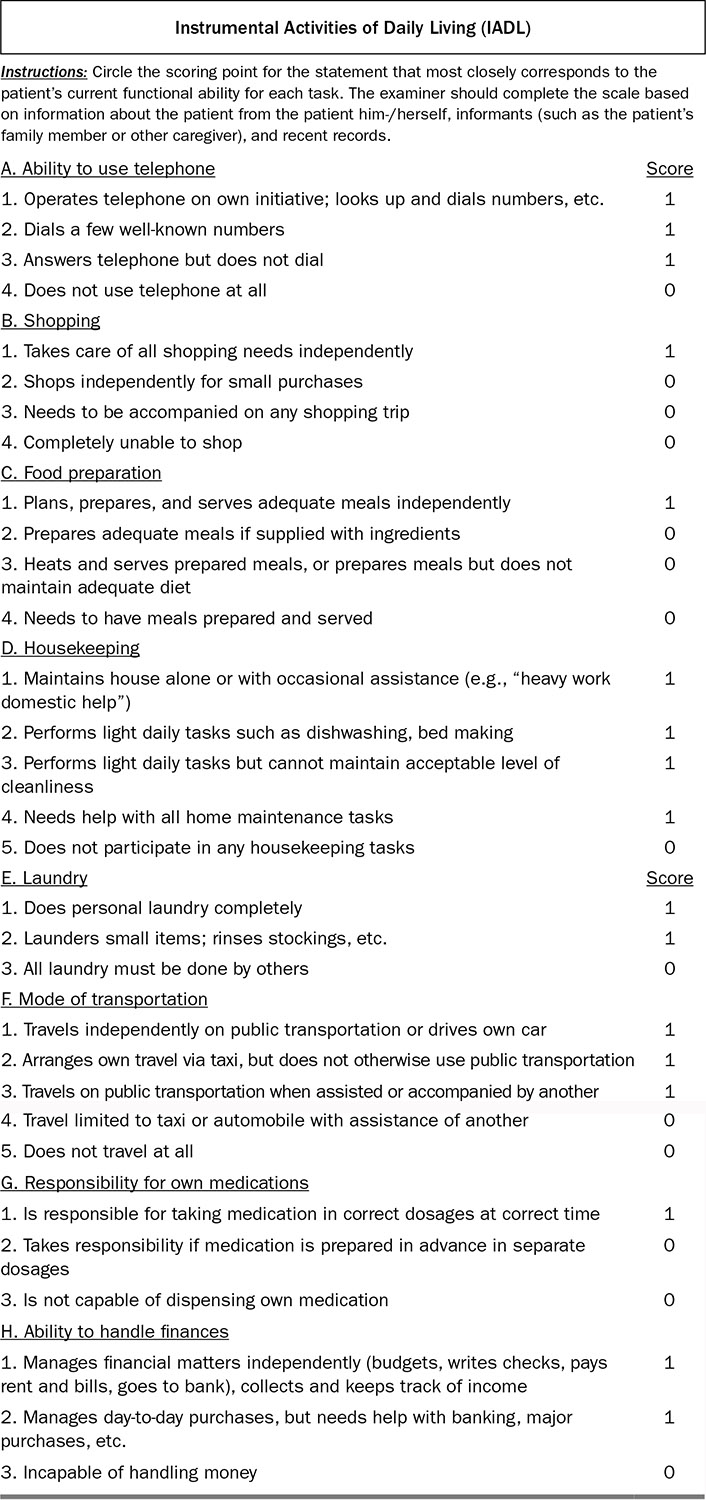

2. IADLs

-The Lawton–Brody scale (10) (Figure 5.2)

The term ADLs was first introduced by geriatrician Dr. Sidney Katz and colleagues from the Benjamin Rose Hospital in 1959. The purpose of their work was to create a tool for measuring changes in physical function in patients with disabling conditions such as stroke and hip fracture. A tool for measuring ADLs was also valuable in determining effects of treatment and for prognostic purposes. Several validated questionnaires for assessing dependency in ADLs and IADLs have been created. These questionnaires may be administered to the patient or a caregiver, or rated by observation (e.g., in a nursing home). The additional assessment of IADLs gives a 39more comprehensive impression of the patients’ degree of dependency in everyday life. To be fully independent in feeding, for example, one also has to be able to go to the store, shop, and prepare a meal—the latter activities are included in IADL scales, such as the Lawton–Brody IADL scale. In clinical practice, it is critical to determine in which activities the patient needs assistance. This knowledge is important to plan for the appropriate level of care. The numerical properties of these scales make them useful in clinical research: both as prognostic factors and outcomes, and as repeated measures to evaluate changes in physical function over time.

FIGURE 5.1 Katz index.

40FIGURE 5.2 Lawton–Brody scale.

Source: Adapted from Ref. (10). Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186.

41PHYSICAL PERFORMANCE MEASURES

Examples of common tools for assessing physical performance:

1. Gait speed (11)

2. Timed up and go test (12)

3. Short Physical Performance Battery (13)

Physical performance measures are objective tests of physical function in which the patients perform one or more standardized tasks, such as walking (gait speed). Gait speed is easily measured by having the patient walk 5 m at a comfortable pace. Number of meters walked is divided by the seconds needed to complete the task, and gait speed is reported in meters per second. Normal gait speeds for healthy women between 70 to 79 and ≥80 years are 1.13 m/sec and 0.94 m/sec, respectively. For healthy men in corresponding age groups, the numbers are 1.26 m/sec and 0.97 m/sec. A gait speed of less than 0.8 m/sec is generally considered slow, and is predictive of poor clinical outcomes such as disability, falls, and institutionalization (5). The timed up and go test is a physical performance test that includes gait, balance, and mobility. The patient sits in an armchair, gets up from the chair, walks 3 m (10 ft) at usual pace, turns 180°, walks back, and sits down again. The result is measured in seconds needed to complete this task. The Short Physical Performance Battery consists of three elements: a balance test, gait speed, and a chair stand test.

ASSESSING FUNCTIONAL STATUS IN GERIATRIC ONCOLOGY

With the large number of tools available to assess physical function, the question remains: Which tools are best suited for onco-geriatric patients? Oncologists have 42traditionally assessed performance status (PS) in cancer patients using indexes such as the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) or the Karnofsky index of PS. The measurement of PS by these indexes and well-established measures is simple and also feasible in geriatric patients. However, in a clinical study of 363 cancer patients with mean age 72 years, the authors identified impairments in ADLs and/or IADLs in a considerable number of patients with ECOG PS less than two (14), indicating that evaluation of dependency in ADLs should be part of the routine patient assessment. The role of objective physical performance measures is well established and will perhaps be determined through future research. To date, no guidelines on how to best assess physical function in geriatric oncology exist, but we recommend, as a minimum, to evaluate PS and use a validated questionnaire on dependency in ADLs and IADLs.

FUNCTIONAL TRAJECTORIES AFTER CANCER TREATMENT

Few studies have looked at functional trajectories after treatment for cancer. In older patients with colorectal cancer undergoing surgery, it was found that approximately one-third of patients had lost ADL function after a median of 22 months follow-up (15). Amemiya et al. found that only a small number of patients over 75 years of age exhibited decline in ADLs 6 months after cancer surgery (16). More studies are needed in this area.

CONCLUSION

Functional dependency is an important factor to consider in older patients with cancer, before treatment, throughout the treatment trajectory, and after completion of treatment. Assessing functional dependency provides the treating physician with a baseline, and serves as a predictor of remaining life expectancy and treatment tolerance. The maintenance of functional independence is a major outcome for older patients treated for cancer, and should be assessed in addition to standard outcomes such as survival and disease progression.

TAKE HOME POINTS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree