Rajal K. Mody, Patricia M. Griffin Keywords Bacillus cereus; Brainerd diarrhea; Campylobacter; ciguatera; Clostridium botulinum; Clostridium perfringens; Cryptosporidium; Cyclospora; disease outbreaks; epidemiology; foodborne diseases; food contamination; food poisoning; gastroenteritis; Giardia; Guillain-Barré syndrome; heavy metal poisoning; hemolytic-uremic syndrome; Listeria monocytogenes; mushroom poisoning; norovirus; paralysis; public health surveillance; reactive arthritis; Salmonella; scombroid poisoning; shellfish poisoning; Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli; Shigella; Staphylococcus aureus; toxins; Toxoplasma gondii; Trichinella; Vibrio; vulnerable populations; Yersinia enterocolitica

Foodborne Disease

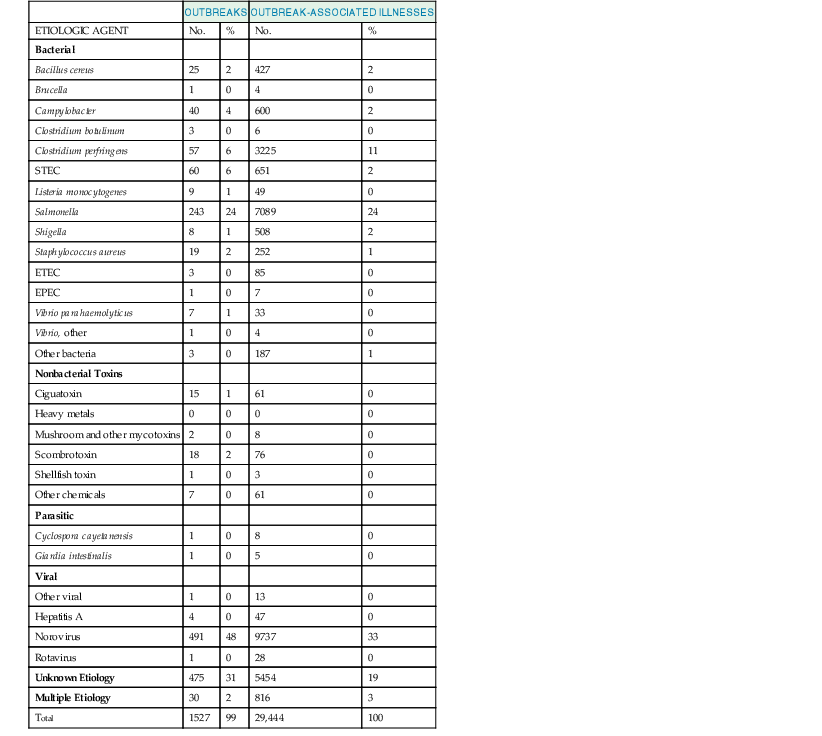

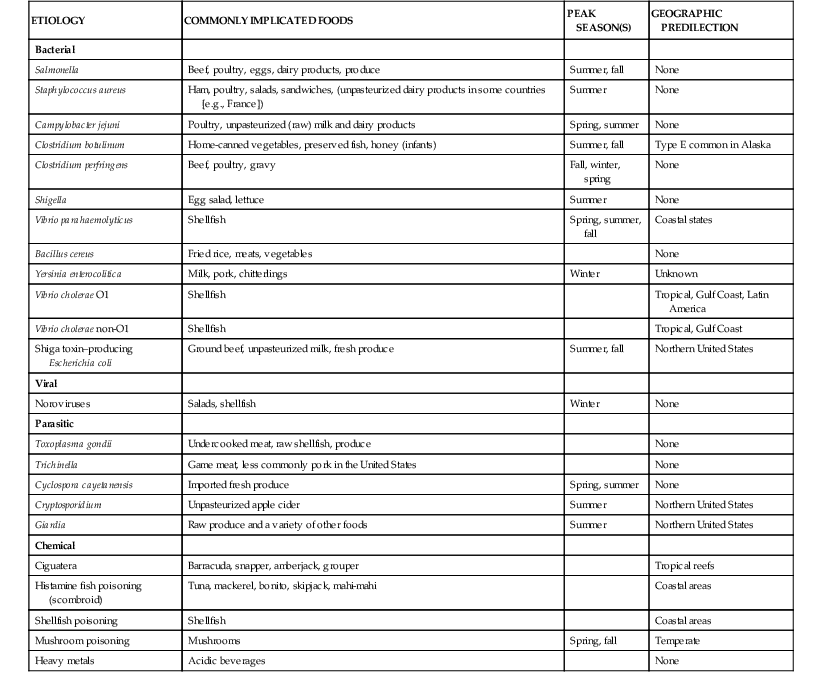

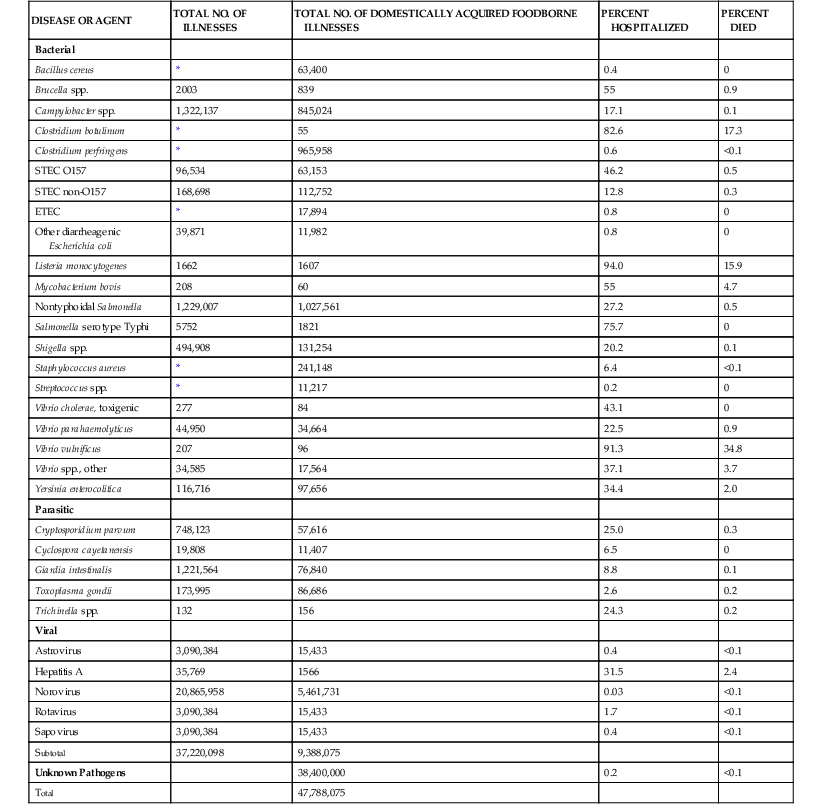

Foodborne diseases result from ingestion of a wide variety of foods contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms, microbial toxins, and chemicals. Many diseases transmitted commonly through food can be acquired via other routes of transmission as well. For sporadic cases (i.e., those that are not part of recognized outbreaks), the route of transmission is generally unknown. Although the majority of foodborne illnesses are sporadic, investigation of outbreaks is an important way to identify the types of foods and contaminants associated with foodborne illness. The major source of information for this chapter comes from foodborne disease outbreak investigations in the United States, and the major focus is on U.S. illnesses. During 2009 and 2010, a mean of 764 outbreaks of foodborne disease, affecting a mean of 14,700 people annually in the United States, were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Table 103-1).1 However, these figures, restricted to outbreak cases, greatly underestimate the magnitude of the problem. The actual number of foodborne illnesses in the United States is unknown but was estimated in 2011 to be approximately 48 million cases, with 128,000 hospitalizations and 3000 deaths each year (Table 103-2).2,3 The annual cost incurred from these illnesses has been estimated to be between $51.0 and $77.7 billion.4 Thus, foodborne diseases are common, can be severe, and lead to considerable economic burden.

TABLE 103-2

Estimated Annual Number of Illnesses Caused by Pathogens That Can Be Transmitted through Food in the United States

| DISEASE OR AGENT | TOTAL NO. OF ILLNESSES | TOTAL NO. OF DOMESTICALLY ACQUIRED FOODBORNE ILLNESSES | PERCENT HOSPITALIZED | PERCENT DIED |

| Bacterial | ||||

| Bacillus cereus | * | 63,400 | 0.4 | 0 |

| Brucella spp. | 2003 | 839 | 55 | 0.9 |

| Campylobacter spp. | 1,322,137 | 845,024 | 17.1 | 0.1 |

| Clostridium botulinum | * | 55 | 82.6 | 17.3 |

| Clostridium perfringens | * | 965,958 | 0.6 | <0.1 |

| STEC O157 | 96,534 | 63,153 | 46.2 | 0.5 |

| STEC non-O157 | 168,698 | 112,752 | 12.8 | 0.3 |

| ETEC | * | 17,894 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Other diarrheagenic Escherichia coli | 39,871 | 11,982 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1662 | 1607 | 94.0 | 15.9 |

| Mycobacterium bovis | 208 | 60 | 55 | 4.7 |

| Nontyphoidal Salmonella | 1,229,007 | 1,027,561 | 27.2 | 0.5 |

| Salmonella serotype Typhi | 5752 | 1821 | 75.7 | 0 |

| Shigella spp. | 494,908 | 131,254 | 20.2 | 0.1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | * | 241,148 | 6.4 | <0.1 |

| Streptococcus spp. | * | 11,217 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Vibrio cholerae, toxigenic | 277 | 84 | 43.1 | 0 |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | 44,950 | 34,664 | 22.5 | 0.9 |

| Vibrio vulnificus | 207 | 96 | 91.3 | 34.8 |

| Vibrio spp., other | 34,585 | 17,564 | 37.1 | 3.7 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 116,716 | 97,656 | 34.4 | 2.0 |

| Parasitic | ||||

| Cryptosporidium parvum | 748,123 | 57,616 | 25.0 | 0.3 |

| Cyclospora cayetanensis | 19,808 | 11,407 | 6.5 | 0 |

| Giardia intestinalis | 1,221,564 | 76,840 | 8.8 | 0.1 |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 173,995 | 86,686 | 2.6 | 0.2 |

| Trichinella spp. | 132 | 156 | 24.3 | 0.2 |

| Viral | ||||

| Astrovirus | 3,090,384 | 15,433 | 0.4 | <0.1 |

| Hepatitis A | 35,769 | 1566 | 31.5 | 2.4 |

| Norovirus | 20,865,958 | 5,461,731 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| Rotavirus | 3,090,384 | 15,433 | 1.7 | <0.1 |

| Sapovirus | 3,090,384 | 15,433 | 0.4 | <0.1 |

| Subtotal | 37,220,098 | 9,388,075 | ||

| Unknown Pathogens | 38,400,000 | 0.2 | <0.1 | |

| Total | 47,788,075 |

* Recent estimates are not available.

ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli.

Modified from Scallan E, Griffin PM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—unspecified agents. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(1):16-22; and Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(1):7-15.

Since 1996, in several sites that now comprise 15% of the U.S. population, the CDC’s Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network has conducted active surveillance for nine pathogens that can be transmitted through food. Comparison of incidence rates in 2012 with rates from 1996 to 1998 shows decreases in the incidence of Campylobacter, Listeria, Shigella, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157, and Yersinia infections (except for Shigella, nearly all of these declines occurred before 2004); no change in Salmonella and Cryptosporidium infections; and an increase in infections caused by Vibrio species (data and figures available at www.cdc.gov/foodnet).5 Clearly, food safety programs need to be intensified.

The spectrum of foodborne diseases has expanded in recent decades in many ways. Noroviruses are now recognized as the most frequent cause of foodborne illness in the United States.3 Known agents continue to be newly recognized as causes of foodborne disease, including enteroaggregative E. coli,6,7 including novel strains that produce Shiga toxin8; Cronobacter (formerly Enterobacter) sakazakii9; and, in South America, Trypanosoma cruzi, causing Chagas’ disease.10 Previously uncommonly recognized food vehicles, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, have become important sources.11,12 Some pathogens have become increasingly resistant to antimicrobial drugs.13,14

New discoveries can be anticipated. Although Clostridium difficile, has been found in retail meat samples, foodborne transmission remains undocumented.15 In addition, identification of more foodborne pathogens is likely as newer molecular diagnostic technology allows detection of more agents.16

Centralization of the food supply in the United States has increased the risk for nationwide outbreaks.17 Global food trade, which is growing faster than increases in food production, forms a complex network that facilitates spread of contaminated foods throughout the world and can delay identification of the source of contamination causing outbreaks.18

Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations

Foodborne disease can appear as an isolated sporadic case or, less frequently, as an outbreak of illness affecting a group of people after a common food exposure. A foodborne disease outbreak should be considered when an acute illness, especially one with gastrointestinal or neurologic manifestations, affects two or more people who shared a common meal. The following section divides acute foodborne diseases into a variety of syndromes based on acute signs and symptoms and typical time of onset after consumption of contaminated food. Agents most likely responsible for each syndrome are described. The incubation period in an individual illness is usually unknown, but it is often apparent in the focal outbreak setting.

Foodborne Syndromes Caused by Microbial Agents or Their Toxins

For this next section, the times shown are those that are typically encountered after exposure to a known foodborne source carrying a pathogen or its toxins.

Nausea and Vomiting within 1 to 8 Hours.

The major etiologic considerations are Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus (see Chapters 196 and 210). The short incubation period reflects the fact that these diseases are caused by preformed enterotoxins. Staphylococcal food poisoning is characterized by vomiting (87% of cases), diarrhea (89%), and abdominal cramps (72%); fever is uncommon (9%).19 Staphylococci responsible for food poisoning produce one or more serologically distinct enterotoxins (SEs A through V, excluding F) but not all cause vomiting.20 The SEs are very resistant to proteolytic enzymes and therefore pass through the stomach intact. All are heat resistant. Strains producing SEA alone account for most of the reported outbreaks of staphylococcal food poisoning in the United States.21,22 In studies of rhesus monkeys, a smaller dose of SEA, compared with doses of SEB, SEC and SED, was required to produce emesis.23 The mechanisms by which enterotoxins lead to emesis may involve vagus nerve stimulation.20

Rarely, other enterotoxigenic coagulase-positive staphylococcal species have been implicated in outbreaks.20 Although enterotoxigenic coagulase-negative staphylococci exist, very few reports have associated these strains with foodborne disease outbreaks.24,25

B. cereus strains can cause two types of food poisoning syndromes, one with an incubation period of 0.5 to 6 hours (short-incubation emetic syndrome) and a second with an incubation period of 8 to 16 hours (long-incubation diarrheal syndrome).26 The emetic syndrome is characterized by vomiting (100% of cases), abdominal cramps (100%), and, less frequently, diarrhea (33%).26,27 The emetic toxin is cereulide, a peptide resistant to heat, proteolysis, and is stable at pH 2 to 11. Cereulide stimulates the vagus afferent nerve by binding to the 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) receptor.28 Rarely, fulminant liver failure may develop via impairment of fatty acid oxidation caused by cereulide’s toxicity to mitochondria.26

Another clue to the cause of staphylococcal and emetic B. cereus illnesses is that their duration is typically less than 24 hours,20,26 and often less than 12 hours.22,27

Abdominal Cramps and Diarrhea within 8 to 16 Hours.

The major etiologic considerations for this enterotoxin-mediated syndrome are Clostridium perfringens type A and B. cereus. In contrast to staphylococcal food poisoning and the emetic B. cereus disease, which are caused by preformed enterotoxins, C. perfringens (see Chapter 100) food poisoning is caused by toxins produced in vivo, accounting for the longer incubation period.19 For B. cereus diarrheal toxins, the toxins themselves are often detected in foods, but it has been postulated that the disease is also caused by ingested vegetative cells that produce enterotoxin within the host’s intestinal tract. It is possible that both modes of infectivity coexist. In C. perfringens type A food poisoning, the most common symptoms are diarrhea (91%) and abdominal cramps (73%); only 14% of patients experience vomiting, and only 5% report fever.19,29 The incubation period is 9 to 12 hours.19 C. perfringens can produce at least 11 toxins in addition to C. perfringens enterotoxin (CPE). Toxinotype A strains always produce α toxin, and those that result in gastrointestinal illness also express CPE, which is produced as the ingested vegetative cells sporulate within the intestine.30 The toxin binds to the apical membrane of epithelial tight junctions in the small intestines, triggering formation of pores through which influx and efflux of water, ions, and other small molecules may lead to diarrhea and cytotoxicity.31

B. cereus strains that cause a similar long-incubation syndrome, including diarrhea (96%), abdominal cramps (75%), sometimes vomiting (33%), and rarely fever,27 elaborate either separately or together with two three-component enterotoxins (hemolysin BL [HBL] and nonhemolytic enterotoxin [NHE]). A single-protein enterotoxin (CytK) has also been described.26,28

Although these illnesses last longer than staphylococcal and emetic B. cereus food poisoning, symptoms usually resolve within 24 to 48 hours.26,32 In contrast, some B. cereus illnesses last several days,28,33 and in one outbreak attributed to B. cereus, some patients had bloody diarrhea and three died.34 In an outbreak of C. perfringens type A infections, severe necrotizing colitis developed in patients with a history of chronic, likely medication-induced, constipation.35 A foodborne infection, fatal in about 20% of patients, is caused by C. perfringens type C in persons with low protein intake; the disease is rare outside of Papua New Guinea.32

Fever, Abdominal Cramps, and Diarrhea within 6 to 48 Hours.

The major etiologic considerations for this syndrome are nontyphoidal Salmonella, Shigella, and Vibrio species, especially V. parahaemolyticus (see Chapters 216, 217, 225, and 226).36,37,38–40 Campylobacter jejuni, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (STEC), and Yersinia enterocolitica should also be considered but typically have a longer incubation period, and fever is less common with STEC (see Chapters 100, 218, and 231). Norovirus does not consistently cause fever but should be considered. These pathogens, with the exception of norovirus, can cause an inflammatory diarrhea, some by invading of the intestinal epithelium and some damaging it via secreted cytotoxins.41,42 Bloody diarrhea and vomiting may occur in a varying proportion. These illnesses usually resolve within 2 to 7 days.36

Nontyphoidal Salmonella is the most common bacterial cause of foodborne illnesses and outbreaks in the United States.1,3 The median incubation period is 6 to 48 hours. However, C. jejuni, with a typical incubation period of 3 to 4 days, is the most common bacterial cause of gastroenteritis, including both foodborne and nonfoodborne routes of transmission.3

Infrequent outbreaks of diarrhea with fever caused by Listeria monocytogenes (see Chapter 208) have been reported among previously healthy persons.43–45 This syndrome is characterized by watery and frequent diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps, headache, and myalgias, with a median incubation period of 20 to 31 hours.

Abdominal Cramps and Watery Diarrhea within 16 to 72 Hours.

The major etiologic considerations for this syndrome are enterotoxigenic strains of E. coli (ETEC) and V. parahaemolyticus. In the United States, other Vibrio species, including V. cholerae (including strains that produce and strains that do not produce cholera toxin), and V. mimicus, cause this foodborne disease syndrome; outbreaks are uncommon, but cases are reported every year.40,46,47 Epidemic cholera manifests as a profuse, watery diarrhea accompanied by muscular cramps; by definition, it is caused by cholera toxin–producing strains of V. cholerae O1 and O139. V. cholerae O141 and O75 can also produce cholera toxin and cause a similar syndrome (see Chapter 217).47,48 C. jejuni, Salmonella, Shigella, STEC, and norovirus may also cause watery diarrhea during this time period. Enterotoxins expressed in vivo are responsible for illness caused by ETEC49 and by cholera toxin–producing strains of V. cholerae.50 The virulence factors of V. parahaemolyticus include both secreted toxins and effector proteins delivered directly into the cytoplasm of the host cell via type III secretion systems.41 The median duration of diarrhea caused by V. parahaemolyticus is 6 days; most patients have abdominal cramping (89%), half have vomiting or fever, and 29% have bloody diarrhea.37 Diarrhea caused by ETEC lasts for a median of 6 days, often accompanied by abdominal cramping for the full duration of illness.51 In one ETEC outbreak, uncommon symptoms included vomiting (13% of cases) and fever (19%).51

Vomiting and Nonbloody Diarrhea within 10 to 51 Hours.

Noroviruses are the most common of known foodborne pathogens (see Chapter 178). They are estimated to cause 5.5 million foodborne illnesses per year in the United States.3 Even more cases of acute gastroenteritis are caused by nonfoodborne transmission of noroviruses, directly from one person to another or by fomite contamination.52 The median incubation period reported in foodborne norovirus outbreaks is 33 hours.53 Norovirus illness is characterized by acute onset of nonbloody diarrhea, vomiting, or both, accompanied by nausea and abdominal pain. Fever occurs in about 40% of patients, is usually low grade, and lasts for less than 24 hours. Symptoms usually resolve in 2 to 3 days, but 12% of patients require medical care and 1.5% are hospitalized for rehydration.53,54 A group of related viruses in the Caliciviridae family, most notably the sapoviruses, can cause similar illness.55

Fever and Abdominal Cramps within 1 to 11 Days, with or without Diarrhea.

Although febrile diarrhea is the most common presentation of Yersinia enterocolitica (see Chapter 231) infection in young children,56,57,58 in older children and adults, the illness may present as either a diarrheal illness or as a pseudoappendicular syndrome; as ileocecitis, consisting of abdominal pain (resembling that of appendicitis); fever; leukocytosis; and, in some patients, nausea and vomiting.59 Joint pain (see postinfection syndromes later), beginning about 1 week after onset of diarrhea, is more common in adults59 Sore throat and rash can affect patients of all ages. The median duration of diarrhea is 2 weeks, but other symptoms may last longer.60 Of note, Campylobacter and Salmonella can also cause an ileocecitis that mimics appendicitis.

Bloody Diarrhea with Minimal Fever within 3 to 8 Days.

The distinctive syndrome of hemorrhagic colitis has been linked to Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC), most often serogroup O157 (see Chapter 226).61 These strains produce one or both types of Shiga toxins (Shiga toxin 1 or 2). Shiga toxins, also referred to as verotoxins, are cytotoxins that damage vascular endothelial cells in target organs such as the gut and kidney.62 In general, strains that produce Shiga toxin 2 tend to be more virulent.63 To cause disease, STEC must also possess additional virulence factors, including those that lead to adherence to the intestinal epithelium.62 The illness is characterized by severe abdominal cramping and diarrhea, which is initially watery but may quickly become grossly bloody.61,64 About one third of patients report a short-lived low-grade fever that typically resolves before seeking medical attention.61,65 Most patients fully recover within 7 days.61 However, overall 6% (15% in children aged <5 years) of patients develop hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which is typically diagnosed about 1 week after the beginning of the diarrheal illness, when the diarrhea is resolving.66 The fatality rate for HUS is 3% in children aged younger than 5 years and 33% in persons aged 60 years or older. For most age groups, deaths in persons without HUS are rare, but 2% of adults aged 60 years or older with only hemorrhagic colitis die.66 Non-O157 STEC are diverse in their virulence properties, causing illness ranging from uncomplicated watery diarrhea to hemorrhagic colitis and HUS. Outbreaks reported in the United States have involved serogroups O26, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O104 (serotype O104:H21, but not O104:H4).67 A large outbreak of infections caused by a strain of enteroaggregative E. coli O104:H4, which had acquired a Shiga toxin 2 gene, occurred in Germany in 2011.8 The median incubation period for illness was 8 days, and HUS developed in approximately 20% of patients.68

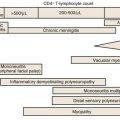

Paralysis within 18 to 36 Hours.

A cluster of two or more illnesses characterized by symmetrical cranial nerve palsies, followed by symmetrical descending flaccid paralysis that may progress to respiratory arrest, is pathognomonic for foodborne botulism (see Chapter 247). The diagnosis should also be strongly suspected in individual patients presenting with these findings. Paralysis may coincide with or be preceded by nausea and vomiting in approximately 50% of patients and diarrhea in nearly 20%, but constipation is common once the neurologic syndrome is well established.69 Botulism is usually caused by one of four immunologically distinct, heat-labile protein neurotoxins, designated botulinum toxins A, B, E, and rarely F.70 The toxins irreversibly block acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction. Foodborne botulism results from ingestion of preformed toxin. Nerve endings regenerate slowly, so recovery typically takes weeks to months70 but is longer for some patients.71 The syndromes of infant botulism and adult intestinal colonization result from ingestion of spores, with subsequent toxin production in vivo.70,72 Clinical suspicion is important for botulism to be correctly diagnosed.73

Persistent Diarrhea within 1 to 3 Weeks.

Parasites, including Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and Cyclospora, are the most common causes of persistent (lasting ≥14 days) foodborne diarrhea (see Chapters 281, 284, and 285).

In the mid-1990s, outbreaks of cyclosporiasis linked to various types of imported fresh produce were recognized in the United States.74 The incubation period averages about 1 week (range, about 2 days to 2 or more weeks), and the most common symptom is watery diarrhea. Other common symptoms include anorexia, weight loss, abdominal cramps, nausea, and body aches. Vomiting and low-grade fever may occur. Untreated illness can last for weeks or months, with a remitting-relapsing course and prolonged fatigue.74

A distinctive chronic watery diarrhea, known as Brainerd diarrhea, was first described in persons who had consumed raw milk.75 After a mean incubation period of 15 days, affected persons developed acute, watery diarrhea with marked urgency and abdominal cramping. Diarrhea persisted for more than a year in 75% of patients. Several restaurant-associated outbreaks and a cruise ship–associated outbreak of a similar illness have suggested that water also transmits the agent, which has not been identified.76–79

Systemic Illness.

Some foodborne diseases manifest mainly as invasive infections in immunocompromised patients. Invasive listeriosis typically affects pregnant women, fetuses, and persons with compromised cellular immunity (see Chapter 208). In pregnant women, infection may be asymptomatic or present as a mild flulike illness; 20% of pregnancies in infected women end in miscarriage.80 Neonatal listeriosis is acquired in utero or at birth and manifests as either early-onset sepsis during the first several days of life or as late-onset meningitis during the first several weeks after birth; the neonatal fatality rate is approximately 20% to 30%.81 In the elderly and immunocompromised persons, listeriosis causes meningitis, sepsis, and focal infections.81 The incubation period ranges from 3 to 70 days, with a median of 3 weeks.

Vibrio vulnificus can cause septicemia after ingestion of contaminated food, typically raw oysters (see Chapter 216). This severe syndrome, often accompanied by bullous skin lesions (Figure 103-1), is seen almost exclusively in patients with impaired immunity, especially those with chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis, alcoholic liver disease, and hepatitis.82 The association with liver disease may be related to portal hypertension, resulting in reduced hepatic phagocytic function, elevated serum iron levels that promote growth of V. vulnificus, or achlorhydria. The overall mortality rate is 30% and varies by the timeliness of antibiotic administration.39,83

On occasion, other Vibrio species, including V. parahaemolyticus and strains of V. cholerae that do not produce cholera toxin cause septicemia.41,46 Nontyphoidal Salmonella can cause bacteremia and focal infections, often in persons at the extremes of age, or in persons with sickle cell anemia, inflammatory bowel disease, or an immunocompromising condition.84

Consumption of foods contaminated with Toxoplasma gondii oocysts excreted from cats or meats containing tissue cysts can cause different manifestations of toxoplasmosis, depending on the host (see Chapter 280).85 In healthy children and adults, up to 90% of infections are asymptomatic, but the remainder lead to nontender, nonsuppurative lymphadenopathy, lasting weeks to months, or chorioretinitis. Fever, malaise, night sweats, myalgias, sore throat, maculopapular rash, and hepatosplenomegaly may occur; other manifestations (e.g., disseminated disease, pneumonitis, hepatitis, encephalitis, myocarditis, and myositis) are rare. Both asymptomatic and symptomatic acute infections lead to latent infections that can reactivate into life-threatening central nervous system infections if a person later becomes immunocompromised. The manifestations of congenitally acquired toxoplasmosis include subclinical infection (which may reactivate during childhood or adulthood), a diverse array of abnormalities at birth (e.g., hydrocephalus, cerebral calcifications, chorioretinitis, thrombocytopenia, and anemia), and perinatal death.85

Several species of Trichinella roundworms cause trichinosis in humans, who are only accidental hosts, when raw or undercooked pork or wild game meat contaminated with larvae is consumed (see Chapter 289). The signs and symptoms depend partly on number of larvae ingested and the person’s immunity. Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps may develop as early as 24 to 48 hours after ingestion, corresponding to the enteral phase of infection. This may be followed by a constellation of signs and symptoms, including fever, myalgias, periorbital or facial edema, headache, or eosinophilia lasting up to several weeks to months, corresponding to the parenteral phase of infection.86

Other infectious agents and diseases with primary symptoms outside the gastrointestinal tract and neurologic systems that can be transmitted by foods include (with a food vehicle example) group A β-hemolytic streptococci (e.g., from cold egg–containing salads),87 typhoid fever (raw produce exposed to human sewage or foods contaminated by asymptomatic human carriers),88 brucellosis (goat’s milk cheese), anthrax (meat), tuberculosis (raw milk), Q fever (raw milk), hepatitis A (shellfish or raw produce), various trematode infections (fish and aquatic invertebrates),89 anisakiasis (fish), and cysticercosis (foods contaminated by Taenia solium eggs shed in human feces of persons with intestinal pork tapeworms).

Postinfection Syndromes.

Although arthropathy has been reported after a variety of enteric infections, most experts agree that the term reactive arthritis should only be applied to infections caused by Salmonella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, or Shigella.90 Reactive arthritis can occur as part of the triad of aseptic inflammatory polyarthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis described by Reiter. Attack rates of reactive arthritis after salmonellosis vary from 1.2% in studies using more objective case definitions to 14% to 29% in studies using more subjective case definitions.90 Although associations between HLA-B27 positivity and reactive arthritis have been identified, the association may exist only for patients with more severe joint or extra-articular involvement. In studies consisting of mostly mild cases, no associations with HLA-B27 were found.90

Worldwide, 31% of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) cases have been attributed to recent Campylobacter jejuni infection (see Chapter 218).91 When preceding diarrheal illness is reported, it typically occurs 1 to 3 weeks before the onset of neurologic symptoms.92 In contrast to botulism, this syndrome is usually manifested by an ascending paralysis accompanied by sensory findings and abnormal nerve conduction velocity.

Several enteric pathogens, including Campylobacter, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Giardia, and norovirus may lead to the development of postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome or other functional gastrointestinal disorders in some patients.93,94

Foodborne Syndromes Caused by Nonbacterial Toxins

A description of all nonbacterial toxins that can cause foodborne illness is beyond the scope of this chapter. Illness caused by natural substances found in staple fruits and vegetables, spices, medicinal herbs and oils, and mycotoxins (other than those in mushrooms) are not covered95; neither are food allergies96 or illnesses caused by additives,95 methylmercury,97 or niacin.98

Nausea, Vomiting, and Abdominal Cramps within 1 Hour.

The major etiologic considerations for this syndrome are heavy metals; copper, zinc, tin, and cadmium have caused foodborne outbreaks.99–105 Latency periods for symptom onset most often range from 5 to 15 minutes after ingestion of contaminated beverages but can be longer with contaminated foods.101 Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps result from direct irritation of the gastric and intestinal mucosa and usually resolve within 2 to 3 hours if minor amounts are ingested. Progression to serious illness and even death is possible if larger amounts are consumed.

Diarrhea within 30 Minutes to 12 Hours.

Outbreaks of diarrhetic shellfish poisoning have been reported from throughout the world but not from the United States. Diarrhea is caused by ingestion of filter-feeding bivalve mollusks, such as mussels and scallops, contaminated with okadaic acid produced by certain dinoflagellates, a type of algae. Vomiting may be present, and symptoms resolve within 3 days.106,107 Outbreaks of azaspiracid shellfish poisoning, causing a similar syndrome, have been reported in Europe.106

Paresthesias within 1 to 3 Hours.

When patients have this symptom, fish and shellfish poisonings are possibilities. Histamine fish poisoning (scombroid poisoning) is characterized by symptoms resembling those of a histamine reaction. Perioral paresthesias, flushing, headache, palpitations, sweating, rash, pruritus, abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are common. In severe cases, urticaria and bronchospasm may also occur.107 Histamine can accumulate in fish flesh that has a high concentration of histidine if postmortem spoilage occurs from inadequate refrigeration. Marine bacteria catalyze the decarboxylation of histidine to heat-stable histamine. Symptoms usually resolve within 24 hours. Unlike seafood allergies, scrombroid fish poisonings have a very high attack rate.108 Puffer fish poisoning, caused by tetrodotoxin, is rare outside of East Asia, but an outbreak in the United States resulted from fish transported in a suitcase. Rapid ascending paralysis occurs, and 14% of patients die.107

Two types of shellfish poisoning present with paresthesias: paralytic (PSP) and neurotoxic (NSP). Mild PSP is characterized by paresthesias of the mouth, lips, face, and extremities. Larger intoxications progress rapidly to include headache, vomiting, diarrhea, dyspnea, dysphagia, muscle weakness or frank paralysis, ataxia, and respiratory insufficiency or failure.106,107 The disease is caused by saxitoxins produced by certain dinoflagellates. Bivalve mollusks and some fish feed on these dinoflagellates; the toxins are concentrated in their flesh. Saxitoxin is heat stable and blocks the propagation of nerve and muscle action potentials by interfering with sodium channel permeability. Patients typically recover in hours to a few days.93

The features of NSP are similar to those of PSP, except they are less severe. Reverse temperature perception may occur.106,107 Brevetoxins produced by certain dinoflagellates are responsible. Brevetoxins cause an influx of sodium into nerve and muscle cells, leading to continuous activation, causing paralysis and fatigue.106 Symptoms typically resolve within 48 hours.107

Paresthesias within 3 to 30 Hours.

The major cause of this syndrome is ciguatera fish poisoning (Table 103-3). Ciguatera is characterized by a broad array of neurologic, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular symptoms. Some characteristic symptoms include facial, perioral, and extremity parestheisias, hot and cold temperature sensation reversal, metallic taste, headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, bradycardia, and hypotension. In severe cases, respiratory distress and death may occur. Gastrointestinal and cardiovascular symptoms resolve in a few days, but neurologic symptoms can last for weeks or years.107,109

Ciguatoxins are lipid-soluble, heat-stable dinoflagellate toxins that open voltage-sensitive sodium channels in neuromuscular junctions. The dinoflagellates are consumed by small fish, which are then consumed by carnivorous fish where the toxins concentrate. Some dinoflagellates that produce ciguatoxins also produce maitotoxin. Although maitotoxin opens cell membrane calcium channels, its role in ciguatera is uncertain given its water-soluble nature.107,109

Vomiting and Diarrhea in Less Than 24 Hours or Neurologic Symptoms in Less Than 48 Hours.

Rare outbreaks of amnesic shellfish poisoning have been reported. Gastrointestinal symptoms predominate in persons aged younger than 40 years. Neurologic symptoms, including headache, visual disturbances, cranial nerve palsies, anterograde amnesia, coma, and death, are more common in persons aged older than 50 years. The illness is caused by the toxin domoic acid, which is produced by certain dinoflagellates and concentrated in shellfish.106,107

Miscellaneous Mushroom Poisoning Syndromes with Onset within 2 Hours.

Several syndromes may occur after ingestion of toxic mushrooms; identification of the syndromes is more important than knowing the associated species (Table 103-4).110,111,112 Species containing ibotenic acid and muscimol cause an illness that mimics alcohol intoxication and is characterized by confusion, restlessness, and visual disturbances, followed by lethargy; symptoms usually resolve within 12 hours. Muscarine-containing mushrooms cause parasympathetic hyperactivity (e.g., salivation, lacrimation, diaphoresis, blurred vision, abdominal cramps, diarrhea). Some patients experience miosis, bradycardia, and bronchospasm. Symptoms usually resolve within 24 hours. Species containing psilocybin cause hallucinations and inappropriate behavior, which usually resolve within 8 hours. Mushrooms containing a disulfiram-like substance, coprine, cause headache, flushing, paresthesias, vomiting, and tachycardia if alcohol is consumed within 72 hours after ingestion. Species containing allenic norleucine cause gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) within 30 minutes to 12 hours after ingestion. Progression to liver injury and acute renal failure typically occurs 4 to 6 days after ingestion. A variety of mushrooms can cause typically mild gastrointestinal irritation.111

TABLE 103-4

Mushroom Poisoning Syndromes

| SYNDROME | COMMONLY IMPLICATED MUSHROOMS | TOXINS |

| Short Incubation | ||

| Delirium, restlessness | Amanita muscaria, Amanita pantherina | Ibotenic acid, muscimol |

| Parasympathetic hyperactivity | Inocybe spp., Clitocybe spp., Boletus spp. | Muscarine |

| Hallucinations, somnolence, dysphoria | Psilocybe spp., Panaeolus spp., Conocybe spp. | Psilocybin |

| Disulfiram reaction | Coprinus atramentarius | Coprine |

| Gastroenteritis | Many | Various uncharacterized irritants |

| Long Incubation | ||

| Gastroenteritis, hepatorenal failure | Amanita phalloides, Amanita virosa, and other Amanitia; Galerina, Cortinarius, and Lepiota spp. | Cyclopeptides (i.e., amatoxins, phallotoxins) |

| Gastroenteritis, muscle cramping, hepatic failure, hemolysis, seizures, coma | Gyromitra spp. | Gyromitrin |

| Gastroenteritis, acute renal failure (temporary) | Amanita smithiana | Allenic norleucine |

| Gastroenteritis, acute renal failure (often irreversible) | Cortinarius spp. | Orellanine |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree