7 Fecal Occult Blood Test

Introduction

Stool tests for screening are known as fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs) because they are designed to detect the presence of blood in the stool. Since colorectal cancer (CRC) or large polyps (larger than 1 to 2 cm) tend to bleed, these tests are designed to detect these types of lesions. Smaller adenomas do not tend to bleed and are not generally detected with FOBT technique. Therefore, stool tests are considered useful for the detection of CRC and advanced neoplasia and are considered less beneficial in CRC prevention. Since the goal of ultrasound screening programs is colorectal cancer prevention, routine use of FOBT over invasive testing is discouraged.1 Presently, FOBT is the second most commonly used screening modality for CRC in the United States, with lower endoscopic examinations being the most common.2 The use of FOBT is on the decline and has decreased from 21.8% in 2002 to 18.7% in 2004 in favor of lower endoscopic examinations, which increased from 45.2% in 2002 to 50.6% in 2004.2 Although the FOBT cannot localize the source of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (Table 7-1) and although polyps and cancers may exhibit only intermittent bleeding, the efficacy of the FOBT as a CRC screening modality for people of average risk has been confirmed in multiple studies.3–6 In this chapter, current recommendations regarding the use of the FOBT for CRC screening and the relative advantages and disadvantages of specific FOBTs are addressed.

Table 7-1 Common Gastrointestinal Sources of Occult Blood

| Bleeding Source | Most Common Lesions |

|---|---|

| Oral | Bleeding gums, dental work |

| Esophageal | Adenocarcinoma, hemorrhagic erosions |

| Gastric | Hemorrhagic erosions, hemorrhagic ulcer, vascular ectasia |

| Small intestinal | Hemorrhagic polyps, hemorrhagic ulcer, vascular ectasia, adenocarcinoma |

| Colonic | Vascular ectasia, diverticular bleeding, adenocarcinoma, polyps |

| Rectal | Hemorrhoids, anal fissures |

Types of Fecal Occult Blood Tests

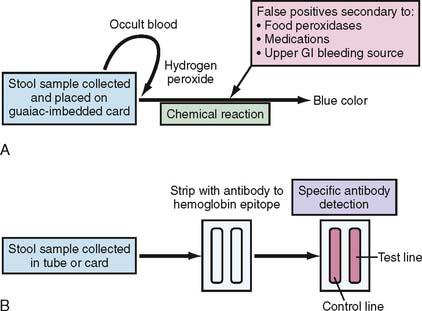

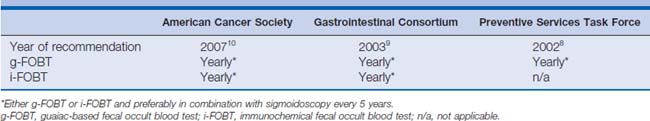

The most commonly used FOBT is the guaiac-based test (g-FOBT). Guaiac is a natural resin extracted from the wood of the Guaiacum officinale plant. The basis of the test depends on the presence of the heme moiety from the hemoglobin that helps hydrogen peroxide (the main component of the developer) oxidize the paper-embedded guaiac into a blue-colored quinone product (Fig. 7-1A). Examples of commercially available FOBTs are shown in Figure 7-2A and B. The most commonly used g-FOBTs used in the United States are the Hemoccult II (Beckman Coulter, Brea, California) and the more sensitive Hemoccult II SENSA elite (Beckman Coulter), used by 72.4% and 13.1% of physicians surveyed, respectively.7 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the Gastrointestinal (GI) Consortium recommend the annual use of guaiac-based test cards prepared at home by patients with two samples from each of three consecutive stool samples8,9 (Table 7-2). A single stool specimen obtained during digital rectal examination is not recommended as an adequate screening strategy for CRC.9

The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) that was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2001 has been added to recent American Cancer Society (ACS) and GI Consortium guidelines for colorectal cancer screening9,10 (see Table 7-2). FIT is based on antibody detection of partial sequences of specific antigenic sites on the globin portion of human hemoglobin (see Fig. 7-1B). Currently, several FITs are commercially available; examples include the Hemoccult ICT (Fig. 7-2C; Beckman Coulter), the HemeSelect (SmithKlineanalyses that concluded Diagnostics, Palo Alto, California), and the InSure (Enterix Inc., Edison, New Jersey) tests. As with the g-FOBT, the ACS also recommends the annual use of multiple stool samples (three consecutive bowel movements) for FIT CRC screening. FIT is processed only in a clinical laboratory, whereas g-FOBT can be processed in a physician’s office.

General Advantages and Disadvantages of Fecal Occult Blood Tests

The primary advantage of the FOBT is that evidence demonstrates a reduction in CRC mortality rate, with an annual g-FOBT decreasing the 13-year CRC mortality by 33%.3 Similarly, the biennial g-FOBT was shown to decrease the 10-year CRC mortality rate by 14% to 18%.4–6,11 Mandel and associates4 in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) described a reduced incidence of CRC with either annual or biennial FOBT after 18 years of follow-up. However, the extensive follow-up and subsequent removal of precancerous lesions were thought to have contributed to the reduced CRC-associated mortality. Another randomized controlled trial by Kronborg and associates5 confirmed the CRC mortality reduction at 18% after 10 years (Table 7-3). Additional studies from Nottingham, UK, and Burgundy, France, reported comparable results with a 15% and 16% reduction of CRC mortality, respectively.6,11 These studies were pooled in two meta-analyses that concluded that biennial FOBT decreased CRC mortality by 14%12 and 15%13 over the first 10 years. There was no evidence-based improvement in CRC mortality if FOBT was performed over longer periods.12 Of note, although most studies report a reduction in CRC mortality, a recent systematic review of biennial g-FOBT screening for CRC did not demonstrate a reduced effect on total mortality rate.14

The second advantage of the FOBT as a CRC screening modality, compared with all other tests, includes its ease of administration. Both the g-FOBT and the FIT are noninvasive tests administered from the patient’s home.15 Frazier and associates16 showed that the g-FOBT compares favorably with other CRC screening modalities with cost-per-year of life saved ($17,805). Sonnenberg and associates,8,17 using 18% as percentage of mortality reduction, calculated an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of $10,463 per year of life saved. The results from the above studies and three others were summarized by Pignone and colleagues.8 The findings were consistent with the cost-effectiveness of other modalities used to screen CRC and other cancers.

Because of its ease of administration and low cost (for the g-FOBT), the FOBT may be of particular benefit as a CRC screening modality in poor countries, where facilities and resources for more invasive tests, including sigmoidoscopies and colonoscopies, are not widely available. For example, in China, with its aging population and lack of a widely subsidized health care system, the FOBT has been proposed as the most compelling method for CRC screening because of its cost-effectiveness and ease of implementation.18

The major disadvantage of the FOBT has been improper implementation. Despite published guidelines by the ACS and the USPSTF,8,10 32.5% of primary care physicians performed office-based FOBTs rather than home-based FOBTs.7 The randomized controlled studies demonstrating a reduction in CRC mortality required the analysis of two stool samples in three consecutively obtained bowel movements.4–6 Collins and associates19 demonstrated that a single g-FOBT on a stool obtained by digital rectal examination in an in-office setting resulted in a sensitivity of only 4.9% for cancer or large polyps compared with 24% using the home-based g-FOBT protocol. Similarly, a single FIT also demonstrated a low sensitivity in detecting both advanced (27.1%) and nonadvanced neoplasms (10.4%) of the colon, especially if the lesions were in the proximal colon.20 Furthermore, a single FIT was unable to detect one third of the invasive cancers.20 The propensity for intermittent bleeding of polyps and CRCs likely contributes to the poor sensitivity of a single FOBT. In addition, the intermittent bleeding likely contributes to the necessity for testing on sequential stool samples and the increased sensitivity of annual FOBTs, compared with biennial screening protocols. Mandel and colleagues3 demonstrated a 33% reduction in CRC mortality rate with annual testing compared with a 21% reduction with biennial testing for 10 years (Table 7-3).

FOBT as a CRC screening modality has seen poor compliance. A CDC survey performed in 1999 reported that only 40.3% of eligible, average-risk subjects for CRC ever had an FOBT and 20.6% received an FOBT within 1 year before the survey.21 Compliance and adherence to CRC screening guidelines were improved with the implementation of a postage-paid return kit and follow-up telephone reminders.22 In addition, education of both patients and physicians regarding FOBTs was recommended after a study of a low-income, average-risk African-American population in Harlem, New York, demonstrated a greater adherence if the patients had more knowledge regarding the FOBT or received relevant recommendations from their physician.23 The use of multifaceted, culturally appropriate patient education materials nearly doubled the rate of FOBT screening in a group of low-income minority patients over a 6-month period.24

Of note, an inappropriate reliance on a repeat FOBT for a positive FOBT has been documented, with one study demonstrating 29.7% of primary care physicians recommending repeat FOBT rather than endoscopic diagnostic testing for positive FOBTs.7 Baig and associates25 reported that 46% of primary care providers relied on a negative repeat FOBT and failed to refer their patients for colonoscopy, or referred them for barium enemas or sigmoidoscopies. Similarly, in a Veterans Administration–based study, follow-up colonoscopy was performed in only 59% of patients with a positive FOBT.26 A colonoscopy should be performed on all patients with a positive FOBT.27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree