Abstract

Screening and diagnosis for diseases of the breast involve coordination between patients and their multidisciplinary team of physicians. The roles of patients and physicians in the evaluation of breast disease are discussed, and the many modalities available for assisting in breast disease evaluation are examined and described, including breast self-examination, clinical breast examination, and breast imaging.

Keywords

breast examination, breast cancer, diagnosis, evaluation, breast disease

Breast disease encompasses a variety of benign and malignant disorders. Although the majority of breast complaints are ultimately noncancerous, breast carcinoma remains the second most common cause of cancer among women and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. In 2015 there was an estimated 234,190 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 60,290 new cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) diagnosed nationwide, with more than 40,000 breast cancer–related deaths. The majority of breast cancer in the United States is detected as an abnormality on imaging; however, patients and clinicians can play an important role in initially identifying and evaluating a suspected lesion. The goal in detecting breast cancer at an early stage is ultimately to improve overall breast cancer survival and patient outcomes. To this end, several strategies exist to help in early detection of breast cancer, including breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE), imaging, and biopsy.

Breast Self-Examination

Breast cancer can be diagnosed after self-detection; however, the relative contributions of systematic self-examination and incidental discovery is not definitively established. BSE formerly played a larger role in breast cancer screening recommendations, but it is no longer recommended by the American Cancer Society (ACS) or by the US Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) because of a lack of clear evidence supporting its benefit. The limitations of breast cancer self-screening are based largely on a study of 266,000 female factory workers in Shanghai, China. One group was instructed in BSE, and the control group was given instructions about lower back pain. Neither group had routine conventional breast imaging or clinical examination. In both cohorts, the size of the tumor and mortality for breast cancer was similar, whereas a higher rate of benign breast biopsies was seen in the BSE group. In another study of 27,421 women enrolled in a health plan in the Pacific Northwest, 75% reported performing BSE, with 27% being reported as having performed an adequate examination. Participants ultimately diagnosed with breast cancer were significantly less likely to report performing BSE. Tumor size and stage were also not associated with the performance of BSE.

Although the USPSTF goes as far as to discourage teaching of BSE based on an unfavorable risk/benefit ratio (with the risks of potential psychological harm, inconvenience, and possibility for overdiagnosis and unnecessary procedures outweighing potential benefits), the ACS maintains that although regular BSE is not warranted for women of average risk, women should become familiar with their own breast examination so that they may report any changes to their health care provider. With this in mind, any discussion between clinician and patient regarding BSE should primarily emphasize the importance of becoming familiar with how one’s breasts normally look and feel. Patients may continue to inquire about and perform when comfortable BSE; clinicians should address both the limitations and potential benefits of BSE as part of a woman’s routine self-awareness and health care. Women who wish to use BSE as a method for becoming more familiar with their breasts’ normal appearance and physical examination should have a systematic approach to looking at and examining their breasts. Instruction on BSE should be prefaced with a discussion of risk factors for development of breast cancer, including patient age, family history (both paternal and maternal) for breast and ovarian cancer, menarche, menopause, obesity, alcohol consumption, and hormone replacement. During this discussion, clinicians should mention that most early-stage breast cancers do not produce symptoms. The most common sign is a painless mass. All women should be informed of the importance of reporting breast changes, including alterations in the contour of the breast, swelling, dimpling, nipple retraction, skin thickening, nipple discharge, or a palpable finding and bring them to the attention of a health care provider. In the premenopausal setting, a lump may be normal if it appears and regresses with the menstrual cycle. A lump that persists past one or two cycles should be brought to the health care provider’s attention. A lump that persists for more than a few weeks in the postmenopausal setting should also be brought to a care provider’s attention.

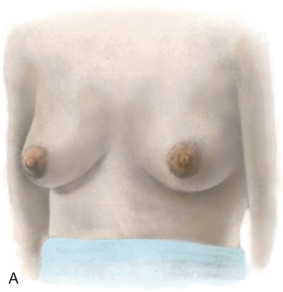

The actual technique for performing a BSE varies but should involve the woman looking at herself in a full-length mirror, with her arms to her side, then over her head, and then to her side with flexion against the side to look for symmetry, dimpling, and retraction ( Fig. 25.1 ). Most women have a slight asymmetry in breast size, and this should be considered normal. A progressive change in size in one breast, whether an increase or decrease, should be brought to the attention of the health care provider. A BSE should also be performed lying down with the arm over the head to allow the breast tissue to splay out evenly over the chest. The examination should be performed with two or three fingers using a circular approach with three degrees of pressure (light, moderate, and deep) and should cover the entire breast from the clavicle to the inframammary fold, laterally to the latissimus, medially to the sternum, and also the low axilla. The entire breast should be examined either in a spoke-wheel fashion or using a vertical-horizontal blind or circular method, covering the entire surface area ( Fig. 25.2 ). This technique should be performed in the same manner on both sides.

Clinical Breast Examination

The role of CBE has a stronger foundation in the early detection of breast carcinoma than BSE; however, limitations in the evidence supporting its routine use are recognized by both the USPSTF and the ACS. The ACS notably shifted their stance away from recommending CBE for women at average risk of breast cancer regardless of age in their 2015 guidelines, citing a lack of evidence showing benefit for CBE performed either alone or in conjunction with mammography, concurrent with an increase in false-positive rates (based on moderate-quality evidence). The most recent USPSTF guidelines in 2009 concluded that the current evidence was insufficient to assess the additional benefits and harms of CBE beyond screening mammography in women 40 years or older; the USPSTF is in the process of updating the breast cancer screening guidelines; however, these are not yet available, and it remains to be seen how CBE will be regarded in their revisions. We continue to recommend CBE as part of our practice in our patient population.

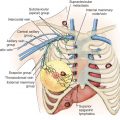

The technique of breast examination should include a thorough inspection and palpation of the entire breast and the draining lymph node–bearing areas. To perform a CBE, the physician should stand in front of the gowned patient. In a manner that allows for minimal disrobement of the patient, both breasts should be inspected with the patient’s arms by her side, with her hands over her head, and finally with her arms to her side with contraction of the pectoralis major muscle. Notes should be taken with regard to size, shape, and symmetry of the breasts. Attention should be made to any changes to the skin, including indentation, protrusions, or skin thickening. The nipple should be inspected for retraction, thickening, flaking, or erosions. After inspecting both breasts, palpation should be performed with the patient in both the sitting and supine position. The entire breast should be examined from the clavicle superiorly to the rectus sheath insertion inferiorly, extending from the latissimus laterally to the sternum medially. Palpation is performed using the pads of the fingers and may again be in the spoke-wheel, vertical-horizontal blind, or circular fashion and should be performed with light, moderate, and deep pressure. Special attention should be made to the lymph nodes in the sitting position. With one arm supporting the woman’s hand, the other hand examines the axilla. The supraclavicular and infraclavicular lymph nodes are best examined from behind with the woman in a seated position. Lymph nodes that measure greater than 1 cm in diameter or that are fixed or matted warrant further diagnostic workup. If a mass is found, a tape measure or caliper is used to estimate its size in two dimensions. The location should be either drawn on a diagram or referenced to a clock time and measured in centimeters from the nipple in a spoke-and-wheel fashion. For a woman who presents with a palpable lump, the detailed history should include length of time present, whether pain is associated with the mass, whether the lump has changed in size since identification, and, in a premenopausal woman, whether the mass changes after menses.

During the examination of the breast, focused attention should be given to the nipple-areolar complex. Manipulation of the nipple should occur only if the patient reports nipple discharge. If present, the clinician should note whether the discharge occurs spontaneously or only with mild manual compression and indicate whether the discharge is unilateral or bilateral, involving one or many ducts. The color of the discharge can help with diagnosis and should always be noted, and accompanied with a description of the offending duct(s). A written description, which may also include a diagram or photograph, may be useful for objective reporting in the patient’s progress notes. Common discharge colors include clear, white, green, brown, black, and red (bloody). Fluid that is brown or black should undergo guaiac testing at the time of the examination to look for breakdown products of hemoglobin. Discharge that is unilateral and bloody or guaiac-positive has a malignancy risk of approximately 20% to 25%; however, the vast majority is caused by benign entities, such as papillomas. Discharge that is bilateral, multiductal, and milky, clear, green, or bluish in color is almost always benign. As many as 50% to 80% of women in their reproductive years may elicit discharge, and 7% of women referred for surgical evaluation have nipple discharge as their primary complaint.

At the time of CBE, risk factors for breast cancer should be reviewed with patients, and the physician should perform a detailed assessment of breast cancer risk by obtaining relevant medical and family histories. It is estimated that 7% to 10% of carcinomas diagnosed in the United States result from an inherited predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer, the vast majority being BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Clinicians should partner with their patients to keep accurate and updated family histories, including maternal and paternal incidences of breast and ovarian cancer dating back two or three generations. Reviewing this information will help identify patients who may benefit from genetic counseling.

Age is an important risk factor for breast carcinoma; currently, a woman living in the United States has a 12.3% chance of developing breast carcinoma. Patients should inform their clinicians of any previous personal history of carcinoma or breast biopsy, and records should be obtained if needed to determine whether prior biopsy specimens contained atypia. A woman’s age at menarche and menopause, as well as parity should be recorded. The use of exogenous estrogen and/or progesterone in the premenopausal and postmenopausal setting should be ascertained. Physicians should discuss the importance of a healthy lifestyle with their patients, emphasizing the role that postmenopausal obesity and excessive or more than moderate alcohol consumption may play in the development of breast cancer. Although no direct evidence links inactivity to an increased risk of breast cancer, intensive physical activity has been linked to a reduced breast cancer risk, with a 2011 review suggesting a 25% risk reduction for the most physically active women compared with the least active women. Although results have varied widely regarding the role of smoking on breast cancer risk, numerous studies have suggested an increased risk of breast cancer among active smokers, and a 2013 meta-analysis found early-age at smoking onset (before menarche and before the first birth) was significantly associated with increased risk of breast cancer development. Clinicians should counsel their patients on the numerous adverse risks of smoking and alcohol use and provide counseling regarding cessation when appropriate.

Once a palpable complaint has been interrogated or at the time of a woman’s CBE at age 40, diagnostic imaging should be initiated. Numerous breast imaging modalities exist to assist the clinician in screening for breast cancer and for diagnosing and managing breast abnormalities detected by both palpation and imaging.

Imaging Modalities

Breast imaging has emerged as a critical component for the early detection of breast cancer and includes but is not limited to mammography, tomosynthesis, ultrasound, and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Investigative modalities designed to overcome limitations with existing technologies are under development, and the field of breast imaging is constantly being advanced. The most conventional imaging modality for breast evaluation is mammography, which has been shown in numerous randomized and population-based studies to help improve early detection of carcinoma, patient outcomes, and survival. Despite these trials, there have been some who suggest against routine screening based on a meta-analysis of a few of the trials, however. The majority of the data and leading organizations with panels on women’s health who comment on cancer screening agree that regular screening mammography should be a part of women’s routine health care.

Mammographic screening guidelines have remained a highly debated topic over the past decade, after the release of the USPSTF’s 2009 guidelines. These guidelines recommend biennial screening for women age 50 to 74, a shared decision-making process for screening women aged 40 to 49 (taking risks and patient values into account), and insufficient evidence to support screening in women older than 75. Recently the ACS updated its recommendations for screening, suggesting that although a shared decision-making process should be used for women 40 to 44, all women age 45 to 54 should undergo annual screening; biennial screening is reserved for women age 55 and older, continuing as long as estimated life expectancy is at least 10 years. These are “qualified recommendations” as opposed to “strong recommendations,” indicating that although clear evidence of the benefit of screening exists, there is less certainty about the balance of benefits and harms or about patients’ values and preferences in these situations, which could lead to different decisions. The ACS also recommends that all women be provided with information about risk factors, risk reduction, and the benefits, limitations, and harms associated with mammography screening. Despite these recent changes from the ACS, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists maintains its current recommendations that women should begin annual screening mammography beginning at age 40 (along with CBE, for all women aged 19 and older) and strongly support shared decision-making between patients and physicians for breast cancer screening practices. The most recent American College of Radiology screening guidelines are similar, calling for annual mammography starting at age 40 for the general population.

Although widespread screening mammography has been in place in the United States for several decades now, screening rates are still far from ideal. The National Health Interview Survey found that in 2010, only 72.4% of women 50 years and older had obtained a mammogram within the past 2 years, with lower rates for women of Asian, American Indian, or Alaska Native race or Hispanic ethnicity. Screening mammograms can detect more than 80% of all breast carcinomas in women without symptoms, establishing a means for early cancer detection and treatment. Although mammograms are more accurate in the postmenopausal setting, there has been improvement in imaging the younger woman with dense breasts after the introduction of digital mammography and more recently tomosynthesis (which is a modification of digital mammography that allows for the acquisition of three-dimensional (3D) thin section data, improving visualization in dense breasts by reducing limitations created by overlapping structures). The vast majority of practices use digital mammography, with accredited full-field digital mammography units making up 97.3% (14,564/14,963) of total accredited mammography units in the United States as of September 1, 2015, and many centers are now obtaining both two-dimensional (2D) digital mammography and 3D tomosynthesis for screening purposes.

In general, mammography should be performed at the same center where films can be serially compared for changes. Expertise in breast imaging is important, especially during the workup of abnormal imaging findings. Recent studies have suggested that radiology image consultation by dedicated breast imagers can influence final management for women with breast cancer, and physicians should consider a specialist’s review in addition to generalist interpretation for appropriate cases. A screening mammogram can detect more than 80% of all breast carcinomas in women without symptoms. Imaging is more accurate in the postmenopausal setting, although with the use of digital mammography, there has been improvement in the younger woman with dense breasts. In the diagnostic setting, it is paramount for the ordering physician to provide the radiologist or breast imaging center with all appropriate information on the location and size of the mass or abnormality, so that appropriate attention and correlation can be made to the concerning region during radiologic assessment.

In addition to mammography, ultrasound plays an integral role in the radiologic assessment of the breast and should be used in the diagnostic setting or to work up an abnormality during the screening process. Focused ultrasound is a valuable tool for the workup of a palpable complaint or mass identified by mammography, and it can be used to help distinguish between the cystic and solid nature of mammographically detected nonpalpable lesions. Ultrasound is particularly useful in evaluating for underlying abnormalities in the premenopausal setting of dense breasts, especially in evaluation of palpable breast lesions. It should be the primary imaging tool for women with palpable lumps who are pregnant, lactating, or younger than 30 years old, and it is the overall procedure of choice during pregnancy. The widespread implementation of whole breast ultrasound screening in the United States has not been successful because of limitations associated with the modality, including the length of time needed to perform the study, operator variability in expertise of the technique, and a high rate of false-positive findings at biopsy. Increasingly, surgeons are becoming more adept at the use of ultrasound in the office as an adjunct to physical examination, and care must be taken in terms of training, qualification, and interpretation before a surgeon implements this in his or her practice. In this respect, the American Society of Breast Surgeons and the American College of Surgeons have taken a leading role in the establishment of guidelines and standards in the use of ultrasound by the surgeon.

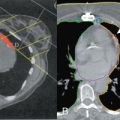

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) is a relatively new imaging modality (with US Food and Drug Administration approval granted in 2011) designed to overcome limitations associated with conventional 2D mammography. DBT can contribute to increased cancer detection and reduced recall rates regardless of breast density but is especially useful in the setting of increased breast density. Data from recent studies highlight additional benefits of tomosynthesis, including significantly reduced false-positive recalls and improved cancer detection when 3D tomosynthesis is added to screening. A recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association demonstrated increases in the positive predictive values for recall and for biopsy, and a decrease in overall recall rates when DBT was used in combination with full-field digital mammography (FFDM), compared with FFDM alone. DBT’s limitations, however, including longer interpretation times, increased radiation doses, additional costs, and difficulties with insurance reimbursements, prevent it from widespread use in breast cancer screening protocols. The American Society of Breast Surgeon’s breast screening recommendations state that breast tomosynthesis may be considered for breast cancer screening, recognizing that neither the ACS nor the USPSTF currently provide specific recommendations regarding mammography-type to be used.

Contrast-enhanced breast MRI is a highly sensitive test with moderate specificity. In the screening population, its use can be justified in certain very high-risk settings, in conjunction with, but not as a substitute for mammography. Women who have an inherited predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Cowden disease, a lifetime risk of breast cancer of greater than 20% to 25%, history of mantle radiation, or a first-degree relative with an inherited predisposition to breast carcinoma without self-testing are likely to benefit from the addition of breast MRI, and clinicians should consider annual screening with both mammography and breast MRI compliant with ACS and National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. In the asymptomatic woman at moderate risk for breast carcinoma based on family history, atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ, or a lifetime risk of breast cancer of 15% to 20%, the risks and benefits of breast MRI should be discussed. One should note the possibility of findings on MRI that will lead to additional imaging, the majority of which will be biopsy-proven benign. Breast MRI should be performed by dedicated breast imagers using at least a 1.5-Tesla magnet, preferably with a dedicated breast coil and breast biopsy capability. The availability of breast MRI has also raised the possibility of potential assistance in the workup of a known cancer. Unfortunately, prospective and retrospective studies have failed to show that prone preoperative MRI is beneficial in improving breast conserving surgery outcomes in terms of reexcision, local recurrence, or overall survival rates.

Other imaging modalities for the evaluation of breast disease are under investigation. Some groups have reported success with scintimammography (molecular breast imaging, MBI) as an adjunct to mammography. This technique uses a breast-specific gamma camera to measure radiotracer uptake of abnormal breast tissue by using technetium sestamibi; with a reported sensitivity approaching up to nearly 70% and an accuracy that is independent of breast density, it has been advocated as a valuable adjunct to mammography, especially for dense breasts. However, its widespread use has yet to be validated by prospective randomized trials or widespread availability. Positron emission tomography and positron emission mammography (which focuses exclusively on the breast) are other imaging techniques being studied; however, these have not been shown to be of benefit in screening or early detection of breast carcinoma and are not currently recommended for these purposes.

Imaging is also important during the evaluation of nipple discharge. Nipple discharge, especially if bloody or guaiac-positive, requires surgical evaluation and intervention in nearly all circumstances. Physical examination and mammography should be routinely performed, and an ultrasound evaluation of the retroareolar ductal system may also be helpful. Ductogram (or galactography) has traditionally been used for lesion identification if mammogram and ultrasound have failed to detect the cause of concerning nipple discharge. This technique, when performed in centers with expertise using this diagnostic test, can be helpful for lesion localization; specifically, lesions may be identified and then preoperatively marked by methylene blue injection or wire guidance to help locate the abnormality and limit the extent of the terminal ductal unit resection. Contrast-enhanced breast MRI has also been recognized by some groups as helpful in identifying underlying lesions in patients with suspicious nipple discharge. More complex and expensive modalities include ductoscopy, where a fiberoptic camera (diameters ranging from 0.4 to 0.8 mm) is inserted into the offending duct either in the operating room or outpatient setting, which allows abnormalities to be identified and either biopsied or resected. However, its benefits over other, more readily available and conventional techniques have yet to be proven, and studies do not currently support its routine use.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree