DEMOGRAPHIC FEATURES

Gastric carcinoma is a malignancy that arises from the gastric mucosa, and its incidence and mortality rates have fallen dramatically over the past 70 years.

1 However, despite these dramatic declines, stomach cancer is the fourth most prevalent cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death worldwide.

2 Approximately 880,000 people were diagnosed with gastric cancer, and approximately 700,000 succumbed to the disease annually worldwide.

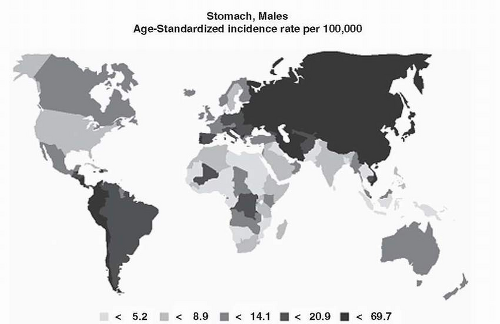

3Sixty percent of gastric cancer cases occur in developing countries. Incidence rates are highest in Eastern Asia, the Andean region of South America, and Eastern Europe, whereas incidence rates are lowest in North America and Northern Europe. The majority of countries in Africa and Southeast Asia have low incidence rates. There is a >20-fold difference in the incidence rates between regions with high incidence rates, such as Korea or Japan, and those with low incidence rates, such as North America. Furthermore, the mortality rates follow the same trends as the incidence rates (

Fig. 2-1).

4To compare the gastric cancer incidence rates in different nations or regions, age-standardized incidence rates (ASRs) and cumulative incidence rates (CRs) until the age of 64 or 74 are commonly used. Between 1998 and 2002, the Yamagata and Miyagi prefectures in Japan had the highest incidence rates in the world (

Table 2-1),

4 with an ASR for men of 70 to 80/100,000 and an ASR for women of around 30/100,000. In addition, the CRs up to 74 years of age for men were 9.4% to 9.7% and for women 3.3% to 3.5%. The areas with the second highest incidence rates were also in Japan and Korea. The populations that show the lowest gastric cancer incidences are whites in the United States, Indians, and Kuwaitis. Gastric cancer incidence rates in the lowincidence regions are approximately 1/10 to 1/14 that of the high-incidence regions, with ASRs of 2 to 7/100,000 for men and 1 to 4/100,000 for women.

The reported decline in the incidence of gastric carcinoma since 1968 is dramatic in lowincidence countries (

Table 2-2). However, declines in high-incidence countries, such as Japan and Chile, have been negligible, which has increased the gap between incidence rates in low- and high-incidence countries.

In the 1930s, gastric cancer was the most common cause of cancer death in the United States and Europe. The decline in gastric carcinoma in the United States since World War II is demonstrated by the following age-adjusted mortality rates for white males: 16.3 per 100,000 between 1950 and 1969 and 7.33 per 100,000 between 1970 and 1994. In fact, in the 50 years following 1950, the incidence of gastric cancer decreased by 60% in Western Europe and North America. A comparison of gastric cancer risk in 34 European countries over the period between 1975 and 2004 revealed that gastric cancer mortality rates decreased continuously in all European nations. From 1990-1994 to 2000-2004, gastric cancer mortality rates in European nations declined from 14.1 to 9.9/100,000 in men and from 6.4 to 4.5/100,000 in women, and this steady fall in gastric cancer mortality rates has persisted in recent years. During the period 2000 to 2004, the highest mortality rate among European nations was in Belarus (29.3/100,000 in men;

11.5/100,000 in women). The lowest incidence areas were Switzerland, France, and the Nordic countries (5-6/100,000 in men). England and Wales had a temporal decline in noncardia gastric cancer incidence, which fell from 8.5 to 4.1/100,000 in men and from 3.8 to 1.9/100,000 in women between 1971 and 1998. A further decrease of at least 24% in the incidence of noncardia gastric cancer is anticipated during the next decade in Western countries, without additional preventive effort.

5Although the reasons underlying the different mortality rates have not been established, improved diet, increased food variety, and reduced prevalence of

Helicobacter pylori infection are possible reasons. Improved diagnosis and treatment are also likely factors underlying the observed reduction in mortality rates.

6 On the other hand, increases in the prevalence of obesity may explain the observed increases in the incidences of gastric cardia cancer in certain Western countries, because the risk of gastric cardia cancer increases with body mass index.

7Gastric cancer is rarely encountered in people younger than 30 years of age, but thereafter, its incidence increases steadily with age, which is a characteristic feature of most carcinomas in both men and women. The gastric cancer incidence rate among men is about twice that among women for individuals older than 50 years of age. On the other hand, the male-to-female ratio is less than two for individuals younger than 50 years of age. The predominance of gastric cancer in men is seen in high-incidence areas as well as in low-incidence areas, suggesting, but not yet proving, that hormonal factors may be involved in gastric carcinoma.

8The incidence of gastric carcinoma increases steeply after 50 years of age in all populations, and an exceptionally high incidence of 673/100,000 has been reported in Miyagi, Japan, for individuals aged 80. The incidence rate for individuals aged 80 in low-risk area such as Los Angeles is 103/100,000. The incidence rate is high even in young individuals living in high-risk countries. The incidence at age 25 is 4.1/100,000 in the Korean population and only 0.3/100,000 in Caucasian residents of Los Angeles (

Table 2-3).

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND HISTOLOGICAL SUBTYPES OF GASTRIC CANCER

The most commonly used gastric carcinoma classifications are the World Health Organization (WHO) and Lauren classifications. The Lauren classification describes two main histological types, the intestinal type, which consists of a gland-forming tumor, and the diffuse type, which consists of discohesive individual cells supported by a dense stroma.

9 The intestinal type is more frequently observed in older patients and follows multifocal atrophic gastritis or intestinal metaplasia, whereas the diffuse type carcinoma occurs commonly in young patients, is not

accompanied by intestinal metaplasia, and can be hereditary. Furthermore, the intestinal-type carcinoma predominates in high-risk areas, whereas the diffuse type is more common in low-risk areas.

10 In addition, men are more likely to have the intestinal-type carcinoma.

11Clinicopathological factors suggest that the environment contributes more to the development of intestinal-type carcinoma than to diffuse-type carcinoma, and conversely, the genetic contribution to the diffuse-type carcinoma may be greater than that to intestinal-type carcinoma.

12 The intestinal-type carcinoma is more likely to show vascular spread and hepatic metastasis, and the diffuse type is less likely to have hepatic metastasis and is more prone to transperitoneal spread.

The Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry of the National Cancer Institute shows that the incidence of diffuse-type gastric carcinoma increased between 1973 and 1990, whereas that of intestinal-type carcinoma decreased.

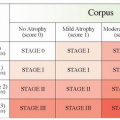

13 In Japan, a similar trend was noted in gastric antral carcinoma relative to gastric carcinoma in the middle third of the stomach, that is, there was a larger proportion of diffuse carcinoma in the more proximal stomach. Differences between the intestinal versus the diffuse types of gastric carcinoma are summarized in

Table 2-4.

14The intestinal-type adenocarcinomas arise in the setting of chronic inflammation. Genetic changes can be detected in intestinal metaplasia, a precancerous lesion that shows p16 methylation

15 or reduced E-cadherin expression in the gastric mucosa of

H. pylori-infected individuals.

16 Intestinal metaplasia is an irreversible lesion, which suggests a permanent change in the genetic and epigenetic features of the gastric stem or progenitor cells. Furthermore, biological detection of genomic instability in intestinal metaplasia has been suggested as a surrogate marker for gastric carcinoma risk and a predictor of its malignant potential.

17