Introduction to the Normal Histology and Physiology of the Stomach

1

1

William Payne

Dongfeng Tan

INTRODUCTION

Understanding the normal anatomy and physiology of the stomach is vitally important in diagnosing disease. Without an accurate understanding of the normal structure and function of the stomach, both at the microscopic and macroscopic levels, it can be difficult to reliably recognize a pathologic condition. This chapter outlines the basic normal gastric anatomy, histology, and physiology.

EMBRYOLOGY

The stomach develops from the caudal aspect of the foregut. Starting around the fourth week after conception, the dorsal border grows faster than the ventral border, creating the lesser and greater curvatures. As the stomach grows, it rotates 90 degrees clockwise, with the ventral border rotating to become the lesser curvature and the dorsal border becoming the greater curvature. In addition, the cranial end moves to the left and the caudal end to the right. The endoderm of the primordial gut forms most of the mucosa of the digestive system. The splanchnic mesenchyme develops into most of the muscle, connective tissue, and associated surrounding soft tissue.1

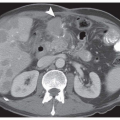

ANATOMY

The stomach lies anterior to the pancreas and extends from just below the diaphragm to its junction with the duodenum. The stomach is surrounded by a rich vascular and neural network, which controls both the secretory action of the stomach and its muscular contractions. The stomach is divided into four main anatomic regions: the cardia, fundus, body (corpus), and antrum. The cardia receives the food from the esophagus, is located just distal to the esophagus, and extends past the esophagus by a few centimeters. The fundus is formed by the left superior aspect of the stomach, which lies under the left diaphragm, and is limited inferiorly by a horizontal line drawn to the left of the incisura cardiaca. The body (corpus) is the largest anatomic region of the stomach, is located between the fundus and antrum, and is bound inferiorly by a line passing from the incisura angularis (on the lesser curvature) to the greater curvature. Distal to the body lies the pyloric antrum, which extends distally to the sulcus intermedius, after which the stomach becomes the pyloric canal. When the stomach is in a nondistended state, prominent rugae (folds) are present on the mucosal surface and are most prominent in the gastric body. As the stomach dilates, these rugae become less apparent.2

The stomach is richly vascularized; blood is supplied primarily along the lesser curvature by the left and right gastric arteries and along the greater curvature by the right and left gastroepiploic arteries. In addition, blood is supplied to parts of the fundus and body along the greater curvature by the short gastric arteries. The gastric arteries have many arterial anastomoses, which help to ensure an adequate blood supply and make the stomach more resilient to vascular damage than other parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) system.2,3 While the venous drainage is much more variable than the arterial supply, the stomach drains venous blood through veins named similarly to the corresponding arteries. The venous system drains into the hepatic portal vein, which in turn drains into the liver.2

The lymphatic drainage pattern of the stomach is important, especially in gastric cancers. Lymphatics are present in the lamina propria and the submucosa. They drain through the muscle into the deeper layers of the stomach.4 While the patterns of drainage do vary somewhat, the drainage patterns tend to follow the course of the arteries and veins. The gastric lymphatics drain in four main drainage patterns, approximately as follows: the proximal aspect of the body and fundus, along the great curvature, drains into the left gastroepiploic and splenic nodes, while the inferior half of the body and the pyloris along the greater curvature drain to the right gastroepiploic nodes and the subpyloric nodes. The body, fundus, and cardia along the lesser curvature drain to the left gastric nodes. The pylorus along the lesser curvature drains to the right gastric, hepatic, suprapyloric, and right superior pancreatic nodes. The lymphatic system from the different gastric areas then drains into the celiac nodes.3,5,6

HISTOLOGY AND PHYSIOLOGY

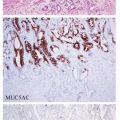

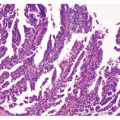

The stomach is made of several distinct functional layers: the mucosa, the submucosa, the muscularis propria, and the serosa. The mucosa comprises three layers: the epithelium; the underlying lamina propria, which is separated from the epithelium by a basement membrane and consists of loose connective tissue, including fibroblasts, histiocytes, and varying amounts of lymphoid cells; and the muscularis mucosae, which consists of thin layers of smooth muscle. The submucosa lies underneath the mucosa and contains blood vessels and nerves, including Meissner plexus. The muscularis propria consists of large bundles of smooth muscle that are arranged in perpendicular patterns to assist peristalsis. The stomach is unique compared to other GI organs in that it has three (vs. two) layers of smooth muscle. The innermost layer is the inner oblique layer, which is unique to the stomach, next is the middle circular layer, and last is the outer longitudinal layer. Auerbach plexus (myenteric plexus) is located between the inner circular and the outer longitudinal layers. Surrounding the stomach is a serosal layer.7,8

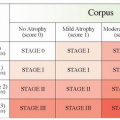

Roughly corresponding to, but not strictly adhering to, the anatomic regions of the stomach, the type of mucosa varies depending on its location. The cardiac mucosa is located in the proximal stomach, adjacent to the gastroesophageal junction. The border between the esophageal and gastric junction, while irregular, has a rather sharp histologic transition. Distal to the cardiac mucosa, fundic-type mucosa lines both the fundus and the body (corpus). At the most distal end of the stomach is the pyloric-type mucosa (sometimes referred to as antral-type mucosa).7,8 This mucosa extends proximally in a triangular pattern, with the tip of the triangle extending further along the lesser curvature than the greater curvature.9 The transition from the pyloric to the fundic mucosa can occur histologically over a 1- to 2-cm region and is less well defined than other histologic transitions, with features of both pyloric and fundic mucosa present.6

Lymphoid Elements

Small primary follicles can occasionally be seen within the normal stomach. However, secondary follicles (with germinal centers) should not be present in the normal stomach. Other lymphoid elements such as the occasional lymphocyte, plasma cell, and mast cell can also be present in the normal stomach.6

Neural Control

The autonomic nervous system helps to control the movement of the stomach. Auerbach plexus primarily controls gastric motility and is located between the inner circular and outer longitudinal layers of the muscularis propria. Meissner plexus (submucosal plexus) primarily controls regional blood flow and gastric secretions. While the enteric system can act independently of external neural stimulus, it is innervated by the autonomic nervous system, which can stimulate or inhibit it.10

Foveolae (Gastric Pits)

Mucous-secreting cells line the surface of the stomach and extend into invaginations of the gastric mucosa called gastric pits. The gastric glands lie beneath the gastric pits and open into them. While the entire surface of the stomach is lined with foveolar epithelium, its appearance (depth of gastric pits, thickness of foveolae) varies depending on the location.7