Pancreatic cancer remains a challenging disease, being the fourth leading cause of death in both men and women in the United States. Patients with pancreatic cancer present with symptoms including jaundice, pruritus, and weight loss, which often herald advanced disease with little chance for curative resection. Multiple imaging modalities are used to diagnose and stage pancreatic cancer. This article discusses the utility of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for diagnosis and staging, and introduces novel EUS-guided therapeutic options for the treatment of pancreatic cancers. EUS-guided fine-needle injection of chemotherapy agents is a promising development in pancreatic tumor treatment.

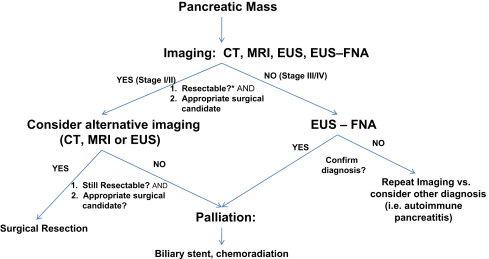

Pancreatic cancer remains a challenging disease, being the fourth leading cause of death in both men and women in the United States. Over 37,000 new cases were diagnosed and 34,000 deaths resulted from pancreatic cancer in the United States in 2008. Even patients who appear curable, those with tumors less than 2 cm confined to the pancreas, have a 5-year survival of only 18% to 24%. In general, patients with pancreatic cancer present with symptoms including jaundice, pruritus, and weight loss. Unfortunately, these symptoms often herald advanced disease with little chance for curative resection. Multiple imaging modalities are used to diagnose and stage pancreatic cancer. This article discusses the utility of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for diagnosis and staging, and introduces novel EUS-guided therapeutic options for the treatment of pancreatic cancers. A proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm is shown in Fig. 1 .

Endoscopic ultrasound equipment and accessories

Three types of echoendoscope from a variety of manufacturers exist: radial, curvilinear, and catheter-based specialty probes. Radial echoendoscopes provide axial images that correspond to the familiar computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) slices, and provide images from 270° or 360°, depending on the manufacturer. Curvilinear echoendoscopes provide an image that is parallel to the shaft of the endoscope. Although debated, many endosonographers prefer the familiar axial imaging associated with radial echoendoscopes to the curvilinear format. The curvilinear aspect, however, allows for the visualization and directing of fine-needle aspiration (FNA), fine-needle injection (FNI), stent placement, and other interventional EUS procedures. Catheter-based ultrasound probes are high-frequency probes that are passed through either a forward-viewing endoscope or a side-viewing duodenoscope to provide direct visualization of a specific area or lesion (ie, submucosal mass, intraductal lesions, or discrete gastric lesion). As with other endoscopes, echoendoscopes are classified as either therapeutic or diagnostic, with the therapeutic versions having a larger overall diameter to accommodate a bigger working channel.

EUS FNA needles are specially designed to fit through the endoscope working channel. FNA needles are available in 19, 22, and 25 gauge. The 19- and 22-gauge needles are used for FNA cytology, whereas the 19-gauge needle is more commonly used for therapeutic injection of agents such as chemotherapy or metal fiducials. There is also a 19-gauge Trucut-type needle that can obtain pancreatic core biopsies under EUS guidance, although this can be technically challenging to use in the transduodenal approach and does not consistently provide adequate tissue cores.

Performance of EUS

Pancreatic EUS is performed as standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Patients generally receive standard moderate sedation with a benzodiazepine and narcotic, although in selected cases patients may receive deeper sedation with propofol or even general anesthesia. Diagnostic procedures can usually be performed in less than 30 minutes, whereas EUS with FNA can take up to 60 minutes. EUS FNA is often performed with an in-room cytologist, who immediately analyzes freshly stained material to determine if adequate cytologic material has been obtained and whether an alternative diagnosis should be considered (ie, infection, autoimmune pancreatitis, or lymphoma).

Performance of EUS

Pancreatic EUS is performed as standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Patients generally receive standard moderate sedation with a benzodiazepine and narcotic, although in selected cases patients may receive deeper sedation with propofol or even general anesthesia. Diagnostic procedures can usually be performed in less than 30 minutes, whereas EUS with FNA can take up to 60 minutes. EUS FNA is often performed with an in-room cytologist, who immediately analyzes freshly stained material to determine if adequate cytologic material has been obtained and whether an alternative diagnosis should be considered (ie, infection, autoimmune pancreatitis, or lymphoma).

Training in EUS

EUS is technically challenging, and generally requires advanced training for safe and appropriate application of this technique. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline for credentialing in EUS requires at least 150 supervised EUS cases, of which 75 should be pancreaticobiliary and 50 supervised FNA cases. To accomplish these requirements, a dedicated fourth-year advanced endoscopy fellowship is often required although not absolutely necessary.

EUS detection of pancreatic masses

Multiple imaging methods can be used to diagnose pancreatic cancer. None is perfect. However, a judicious combination of several methods usually allows for accurate diagnosis and staging of the disease. The relevant imaging modalities include transabdominal ultrasound (TUS), CT, MRI, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), positron emission tomography (PET), and EUS. Recent studies report a sensitivity of EUS for the detection of a pancreatic mass ranging from 87% to 100%. In general, when a patient presents with any combination of abdominal pain, weight loss, and jaundice, the diagnostic imaging choice is either a CT scan or TUS. TUS performs poorly in comparison with other imaging methods, with a sensitivity between 60% and 70% and a specificity between 40% and 50%. In comparison, CT in several systematic reviews has reported sensitivity for the detection of a pancreatic mass ranging from 63% to 92%. Although EUS in most studies shows a slightly better diagnostic performance, the continued improvements in resolution with multidectector CT will likely favor CT over EUS as the initial imaging choice, given its additional ability to detect distant metastasis. A reasonable alternative to CT is a pancreatic MRI scan. The sensitivity of MRI for detecting pancreatic cancer ranges from 88% to 96%.

EUS is very sensitive for detecting pancreatic masses. In a patient with suspected pancreatic cancer based on obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain, weight loss, or unexplained pancreatitis, equivocal CT or MRI scans should be followed with EUS. This imaging is especially important if either a dilated common bile duct or pancreatic duct is seen on noninvasive imaging studies, or if there is a vague fullness in the pancreas. Missed tumors are often small adenocarcinomas near the confluence of the pancreatic duct and bile duct, neuroendocrine tumors, or diffusely infiltrating adenocarcinomas ( Fig. 2 ). EUS, CT, and MRI have respective sensitivities of 93%, 53%, and 67% for detecting tumors smaller 3 cm or less. For tumors smaller than 2 cm the reported diagnostic superiority of EUS is even more pronounced, with sensitivities of 90%, 40%, and 33% for EUS, CT, and MRI, respectively. Improvements in CT technology have narrowed this gap, with a recent study by DeWitt and colleagues reporting a sensitivity of 89% and 53% for EUS and CT, respectively.

EUS FNA for cytologic diagnosis of pancreatic cancer

EUS is now the diagnostic tool of choice when it is necessary to obtain a tissue diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. Cytologic diagnosis can be obtained in multiple ways including CT-guided, ultrasound-guided, brush cytology, and EUS FNA. The addition of FNA to EUS greatly improves the sensitivity and specificity of EUS for the diagnosis ( Fig. 3 ). The average reported sensitivity and specificity of EUS FNA is 85% and 98%, respectively. Therefore a positive result from an FNA is very reliable, whereas a negative result does not rule out pancreatic cancer and further investigation is often required when pancreatic cancer is still suspected. EUS FNA is also very successful in the setting of previously failed or nondiagnostic biopsy by other methods, such as ERCP biliary brushing or percutaneous FNA, in which EUS FNA achieves a sensitivity of 90% to 94%.

A well-recognized limitation of EUS for diagnosis of pancreatic cancer is in the setting of either acute or chronic pancreatitis. Several investigators have reported case series in which patients with pancreatitis and high suspicion for pancreatic cancer, but a negative EUS, have had a missed pancreatic neoplasm. A negative EUS or EUS FNA in the setting of pancreatitis, acute or chronic, should be followed by a repeat imaging study in 3 to 6 months or after resolution of pancreatitis, whichever is sooner, to look for a previously missed pancreatic lesion.

Risks of EUS FNA

EUS FNA is widely performed and has an excellent safety record. However, it is important to realize that there is the potential for complications, which occur in approximately 1% to 2% of cases. The most common complications include acute pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation (usually duodenal). In addition, there is the potential of seeding malignant cells along the FNA path. Because EUS FNA of pancreatic head tumors is performed through a transduodenal approach and these tumors are removed with a pancreaticoduodenectomy, this area is removed during surgery and so local seeding is not an issue. However, for lesions located in the pancreatic neck/body/tail that undergo transgastric EUS FNA, there have been rare cases of malignant seeding of the gastric wall.

EUS elastography

Although EUS is already excellent for imaging the pancreas, it may be improved with the addition of elastography, which is a new technology that provides a measure of tissue elasticity. This technique has not yet gained widespread acceptance but is of increasing interest. Malignant tumors are generally harder than surrounding tissue, and therefore elastography may provide improved ultrasound characterization and targeting for FNA. A multicenter European study found the sensitivity and specificity of EUS elastography for diagnosing pancreatic malignancy to be 92% and 80%, respectively, compared with 92% and 69% for standard EUS. For peripancreatic lymph nodes, the sensitivity and specificity of EUS elastography was 92% and 83%, compared with 79% and 50% for standard EUS. There was good interobserver agreement for EUS elastography of both masses and lymph nodes. What the exact role of EUS elastography will be in the future is uncertain, because endosonographers using EUS FNA for tissue diagnosis are already very successful in obtaining tissue diagnosis of tumors, and lymph node staging is currently much less important than vascular invasion for determining resectability. However, elastography might help in challenging cases of suspicious lesions and negative FNA cytology. It is also possible that elastography could help guide FNA and perhaps reduce the number of FNA passes.

Utility of EUS FNA for suspected pancreatic cancer

A large multicenter study found an overall diagnostic rate of 72% for malignancy in patients undergoing EUS FNA for solid pancreatic masses. Of importance is that there can be wide variation in the diagnostic yield between endosonographers and EUS centers, with a variety of potential explanations including physician experience, in-room cytology, pathologist experience, and prevalence of underlying chronic pancreatitis.

Not all pancreatic masses need EUS FNA. If a patient has typical signs of acute obstructive jaundice, has a small well defined mass, and is young, consideration could be given toward proceeding directly to pancreatic resection, given the high pretest probability of cancer and to avoid any potential complications from EUS FNA such as acute pancreatitis, which could compromise future surgery.

However, in some cases EUS FNA should be performed on pancreatic masses before surgery. The most compelling reason for this is suspicion of the increasingly common diagnoses of autoimmune pancreatitis and autoimmune cholangitis. These inflammatory diseases can mimic pancreatic or biliary cancer because they can appear as masses or biliary strictures. The most classic forms include a diffusely enlarged pancreas on CT scan, which on EUS is diffusely hypoechoic ( Fig. 4 ). The diagnosis is usually made by obtaining serum IgG subtype 4, although it can also be made from pancreatic FNA or core biopsy (with or without IgG subtype 4 tissue staining). It is important not to miss this diagnosis because nonoperative treatment with prednisone usually results in complete remission. EUS FNA can also help exclude other less common causes of pancreatic masses such as pancreatic endocrine tumor, lymphoma, and tuberculosis.