13 Endoscopic Techniques in Colorectal Neoplasia

Endoscopic Resection

Endoscopic resection is gaining increasing acceptance as a viable management option for early gastrointestinal malignancy. For the purpose of this chapter, early gastrointestinal malignancy refers to lesions confined within the submucosal layer with no or low risk of lymph node metastasis, such that the endoscopic resection is potentially curative, obviating the need for more invasive surgical therapy.1

Superficial lesions have been classified into three main types by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association: type I polypoid, type II nonpolypoid and nonexcavated, and type III nonpolypoid with an ulcer. Type I lesions are further subclassified into type Ip (pedunculated) and type Is (sessile) lesions. Type II lesions are further subclassified into type IIa (slightly elevated), type IIb (completely flat), and type IIc (slightly depressed) lesions.1 In general, type IIc lesions tend to be more invasive at smaller tumor size when compared with type IIa lesions. Furthermore, the larger diameter of type II lesions is associated with deeper depth of invasion.

Submucosal lesions in the colon are divided into sm1, sm2, and sm3 lesions, based on depth of invasion. Submucosal lesions in the upper third sector (sm1) are further subdivided into a, b, and c, based on the horizontal spread of the lesion. In the colon, the risk of lymph node metastasis is directly correlated with the depth of invasion and has not been shown to occur before the penetration of the submucosal layer.1 The cut-off commonly used for safe endoscopic resection of early colonic neoplasia is depth of invasion into the submucosal layer of less than 500 μm.2

Indications

The currently accepted indications for endoscopic resection in early colorectal cancers include: (1) well- or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; (2) cancer confined to the mucosa layer or intramucosal cancer type IIa less than 20 mm; (3) cancer confined to the mucosa layer or intramucosal cancer type IIb or IIc less than 10 mm; (4) cancer superficially invading the submucosal layer (sm1a and b, less than 500 μm from the muscularis mucosa layer); and (5) laterally spreading tumor.3

Techniques

Polypectomy

The most fundamental technique in endoscopic resection is simple polypectomy, also known as the “just-cut” method with a standard polypectomy snare. This technique is most useful for lesions with a small stalk, in which the polypectomy snare is advanced through the working channel of the endoscope and enclosed around the stalk.4 Then, either as cold guillotine or with electrocautery, the lesion is transected off the stalk.

Endoscopic Mucosal Resection

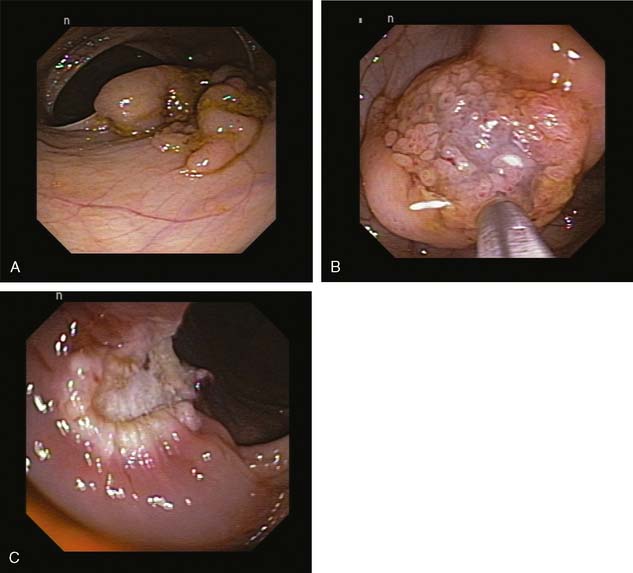

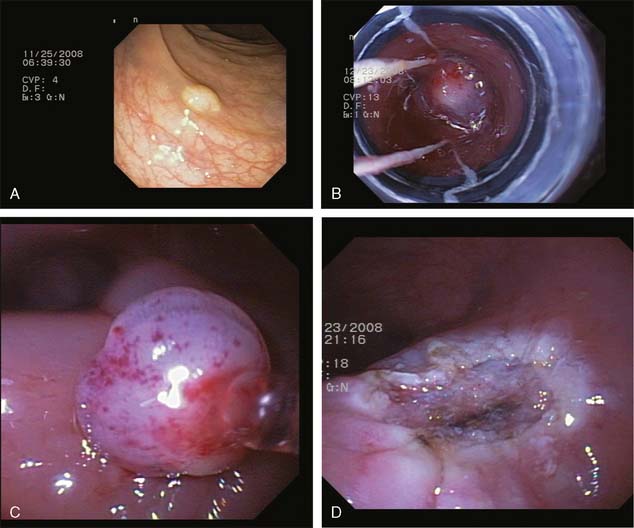

The techniques of EMR can be further divided into those that require suction and those that do not. Two subtypes of EMR techniques do not require suction. The first is the inject-and-cut method, which is akin to a saline-assisted polypectomy (Fig. 13-1). Submucosal injection is performed with creation of a submucosal cushion under the lesion, and a standard endoscopic polypectomy snare is used to cut the lesion. The second variation is the inject lift-and-cut method, which is a combination of the submucosal injection with the lift-and-cut technique of polypectomy. Submucosal injection is performed by creating a cushion, and then a grasping forceps or a snare is used to grasp and lift the lesion, where a second snare is passed through the second working channel of the double-channel endoscope to resect the lesion.

Two subtypes of EMR techniques require endoscopic suction to be applied for resection. However, both methods, which were adopted from the upper gastrointestinal tract, require judicious use of the suction because the wall of the colon is significantly thinner than the wall of the stomach. EMR-cap involves fixing a transparent cap at the end of the endoscope.5 A specially designed snare is positioned on the inner lip of the cap, while the endoscope is away from the lesion. The cap with the preloaded snare is then positioned over the lesion, and suction is applied to bring the lesion into the cap. The snare is enclosed around the lesion within the cap, and electrocautery is applied to cut the lesion. In EMR ligation, a standard variceal band ligation device is used with a submucosal injection.6,7 The band ligation device is positioned above the lesion and the submucosal cushion; after suction is applied bringing the lesion into the cap, the band is deployed around the lesion as in the standard variceal banding technique. Then, a specially designed hexagonal electrocautery snare is advanced through the banding cap device to cut the lesion either just above or below (Fig. 13-2).

Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection

Although EMR techniques are simple for smaller lesions, the ability of EMR to resect en bloc large, flat lesions is limited by size, especially if one of the cap-suction–based EMR techniques is used. ESD involves marking the margins of the lesion with electrocautery and generous submucosal injections. A circumferential submucosal incision is made with specialized endoscopic electrocautery knives, and dissection of the lesion from the underlying layers is performed to complete the resection. Various electrocautery knives have been developed for ESD, including needle knife, insulated-tip diathermic knife, flex knife, hook knife, triangle-tipped knife, and splash needle, each of which has specific advantages and limitations. ESD is a highly specialized technique that is not yet widely available outside of Japan and other Asian countries, but it is increasingly gaining momentum. ESD is generally more time-consuming and labor-intensive compared with other methods of endoscopic resections, but it is more reliable in allowing complete en bloc resection of lesions with a lower likelihood of local recurrence. ESD is also associated with a potential for higher risk of complications, including perforation. Review of the literature indicates a perforation rate of around 4% to 10% for ESD and 0.3% to 0.5% for EMR.8,9

Submucosal Injection.

In endoscopic resection—regardless of the technique—it is critical to maintain an adequate submucosal cushion during the procedure to decrease complication rate. Furthermore, mucosal resection of the lesion should not be attempted if the lesion does not “lift” during the submucosal injection, since this is a good predictor of deeper invasion of the tumor into the submucosal layer. Various solutions that have been studied for submucosal injection during EMR and ESD include normal saline, hypertonic sodium chloride solution, hyaluronic acid, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, glycerol, dextrose, albumin, fibrinogen, and autologous blood.10

Outcomes

Kudo11 reported his experience with 674 cases of early colorectal cancer, of which endoscopic resections were performed in 633 cases.11 Ten patients underwent surgical resection following endoscopic resection because of deep submucosal invasion. None of the patients who successfully underwent complete endoscopic resection developed local recurrence or distant metastasis during the follow-up period.1,11

Tanaka and colleagues12 reported their experience in 81 patients with large laterally spreading tumors (mean diameter of 31 mm) who underwent endoscopic resection, half of whom underwent en bloc resections. Submucosal invasions (less than 400 μm) were detected in seven patients, three of whom went to surgery. Locally recurrent disease occurred in 6 of the 78 endoscopic resection follow-up group, and all were successfully treated with repeat endoscopic resection. None of the 78 endoscopic resection patients developed lymph node or distant metastatic disease after a mean follow-up of 5 years.1,12

Colorectal Self-Expandable Metal Stents

Despite increased awareness of the benefits of routine colorectal cancer screening, up to one third of patients with colorectal cancer present with acute obstruction.13–15 Of those who present with acute obstruction, up to one third will be unresectable owing to local tumor infiltration, metastatic disease, or severe medical comorbidities.14,16,17

Acute colonic obstruction is considered a surgical emergency, since persistent obstruction may lead to colonic ischemia, sepsis, and perforation. Traditionally, the management involved a three-stage process: (1) emergent surgical decompression of the acute colonic obstruction with decompressing colostomy, (2) primary resection of the tumor, and (3) reestablishing bowel continuity with colostomy take-down.18 The current surgical standard of care for acute malignant obstruction of the distal colon involves Hartmann’s procedure,15,19 in which a colostomy is formed for decompression with the resection of the primary tumor. The diversion colostomy is crucial because of the concern for the disintegration of the surgical anastomosis by the fecal stream from an unprepped colon.20 Thus, the patient must wait at least 8 weeks after the initial surgery before the colostomy can be safely reversed. However, many have to wait much longer to ensure integrity of the colonic mucosa and the surgical anastomosis, since most of these patients also require adjuvant chemotherapy. Furthermore, 25% to 50% of the patients are not even able to undergo the second surgery for the colostomy take-down procedure on the basis of medical comorbidities and remain with a permanent colostomy.15,21 Other surgical options include radical resection with an ileo-rectal anastomosis and intraoperative colonic lavage.20

Regardless of which surgical technique is adopted, emergency surgical decompression of acute malignant colonic obstruction is associated with a mortality rate of 15% to 20% and a morbidity rate of 39% to 50%.14,22–25 In contrast, if elective surgery is performed, the mortality rates can decrease to 0.9% to 6.0%.22 Furthermore, emergent surgery is more likely to result in a temporary or permanent colostomy, given that the poorly prepped, dilated colon makes primary anastomosis imprudent.14 In fact, rates of primary anastomosis were almost twice as high for patients who underwent elective surgery after colonic stenting decompression compared with patients who underwent emergency surgery.26

Given the high mortality and morbidity rates associated with emergent surgical decompression of the colon, the technique of colonic stenting as a bridge intervention to elective surgery and as a palliative intervention was introduced. As a natural extension of the techniques of stenting of esophageal, gastric outlet, and biliary obstruction, endoscopic stenting for malignant colonic obstruction was first reported in 1992 by Spinelli and colleagues.27 Since that time, the use of endoscopically placed colorectal self-expandable metal stents has been gaining widespread acceptance as a viable and effective management option for malignant colonic obstruction.

Several studies have compared the outcomes of patients with acute malignant colonic obstruction who underwent a colorectal self-expandable metal stent decompression followed by elective colonic resection and those who underwent an emergency surgical decompression and resection. A meta-analysis of 10 studies compared colonic stents with emergent surgery for malignant large bowel obstruction.28 The meta-analysis included 451 patients, of whom 244 (54.1%) had undergone a colonic stent placement attempt. Colonic stent placement was successful in 226 patients (92.6%) with individual reported success rates ranging from 88% to 100%. There were 25 deaths in the surgical group (12.1%), compared with 14 deaths in the stent group (5.7%). In patients with primary colorectal cancer, patients in the stent group had significantly lower rates of mortality (odds ratio [OR] 0.40; P = .02) and medical complications (OR 0.17; P < .001). The average length of hospital stay was almost 7 days less in the stent group (−6.59 days; P < .001), and significantly fewer patients in the stent group required an intensive care unit (ICU) stay after the decompression intervention (OR 0.07; P < .001). The rate of long-term need for stoma was also significantly lower in the stent group (OR 0.04; P < .001).

Indications

Endoscopically placed colorectal self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) for acute malignant colonic obstruction are indicated in patients with resectable disease who need a temporary decompression as a bridge to definitive curative resection and in patients with unresectable disease who need long-term palliative intervention.29 SEMS decompression transforms an emergent colonic surgery to an elective surgery with the ability to adequately prep the bowel and to better assess the disease status before proceeding with curative intent. Thus, for patients who undergo colorectal stent placement as a bridge to surgical therapy, the endoscopic decompression may allow for a one-stage colonic resection operation with a primary anastomosis.29 Furthermore, although colonic segmental resection for malignancy following decompression was traditionally reserved for the open laparotomy approach, several studies have shown that successful laparoscopic resections can be performed after adequate decompression with SEMS in this population.30–33

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree