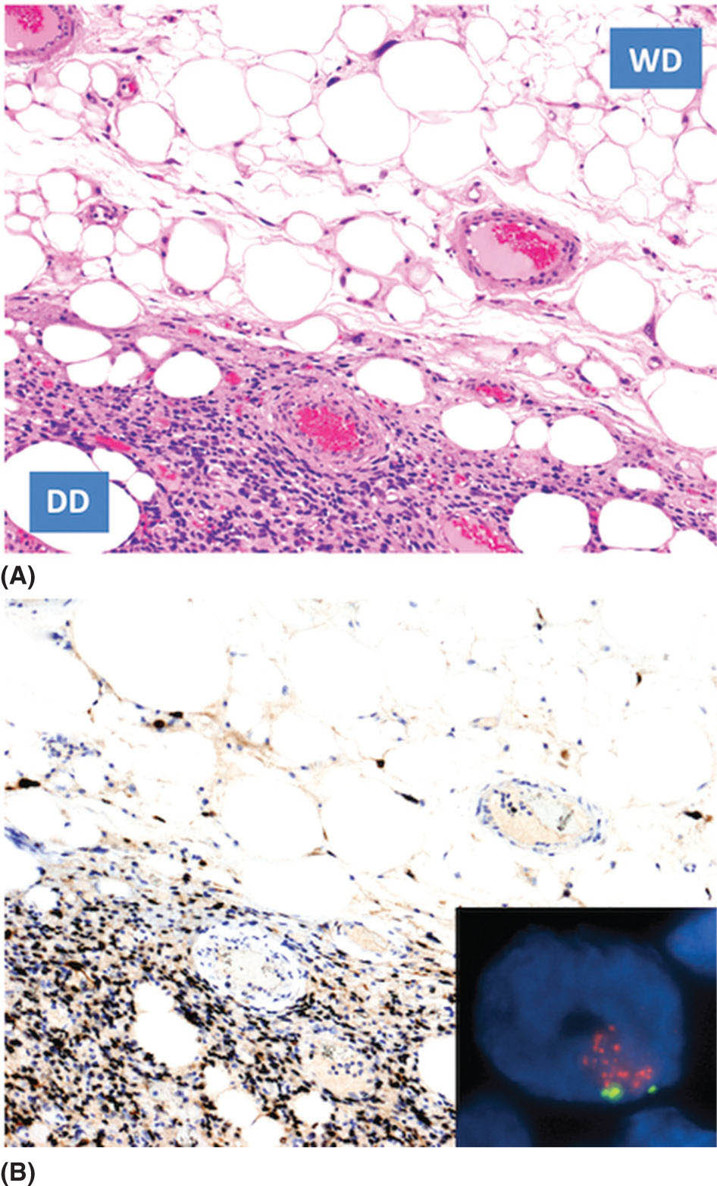

1259 Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma Dedifferentiated (DD) liposarcoma is a high-grade, adipocytic malignancy and can be considered a part of a spectrum of diseases that include its low-grade counterpart, well-differentiated (WD) liposarcoma. A patient’s tumor can be entirely WD, WD with focal area(s) of DD disease, or rarely, entirely DD without a WD component. The presence of dedifferentiation in a tumor changes the disease biology, making the tumor more aggressive and conferring metastatic potential. WD/DD disease is distinct from other subtypes of liposarcoma, such as myxoid round cell and pleomorphic. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for patients with localized disease in WD/DD liposarcoma. This chapter focuses on DD liposarcoma within the context of WD/DD disease. It highlights the differences that arise with the presence of DD liposarcoma, especially how this may impact decision-making and management. The chapter concludes with additional pearls and pitfalls, along with a discussion of active issues for further investigation. decision-making, dedifferentiated liposarcoma, management, surgery, treatment, well-differentiated liposarcoma Decision Making, Disease Management, General Surgery, Liposarcoma, Therapeutics INTRODUCTION Dedifferentiated (DD) liposarcoma is a high-grade, adipocytic malignancy and can be considered a part of a spectrum of diseases that include its low-grade counterpart, well-differentiated (WD) liposarcoma. A patient’s tumor can be entirely WD, WD with focal area(s) of DD disease, or rarely, entirely DD without a WD component. The presence of dedifferentiation in a tumor changes the disease biology, making the tumor more aggressive and conferring metastatic potential. WD/DD disease is distinct from other subtypes of liposarcoma, such as myxoid round cell and pleomorphic, which will not be covered in this chapter. WD/DD liposarcoma is almost exclusively a disease of adults without any gender or race predilection. There are no known risk factors or associated genetic syndromes. For patients with WD/DD liposarcoma, symptoms may vary by body location, but overall, they are frequently vague and nonspecific. Some patients may be completely asymptomatic, their tumors discovered only after imaging is done for another purpose. On cross-sectional imaging (e.g., MRI or CT), WD/DD liposarcoma appears as a well-defined lipomatous mass with thickened internal fibrous septa. Dedifferentiation is suspected when focal nonlipomatous areas are seen, particularly if these areas have contrast enhancement or necrosis. Ultimately, the gold standard of diagnosis for WD/DD liposarcoma relies on histologic examination of the tissue (e.g., obtained from core-needle biopsy). The diagnosis can be confirmed with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for chromosomal amplification at 12q13–15, the pathognomonic genetic feature of WD/DD liposarcoma. This amplicon includes several key genes including MDM2 and CDK4. Recently, further genetic differences between WD and DD disease have begun to be elucidated. WD/DD liposarcoma can occur anywhere in the body, including the extremities, trunk, head/neck, and commonly, the retroperitoneum, where in the latter case, tumors can reach very large size. Tumors with dedifferentiation are far more common in the retroperitoneum, whereas DD liposarcoma is rare elsewhere in the body. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for patients with localized disease in WD/DD liposarcoma. Complete resection is the goal but may be challenging, particularly for retroperitoneal tumors, given their large size and potential invasion of major visceral organs and critical structures. The role of radiation therapy to improve local control in WD/DD liposarcoma is controversial. If given, delivery is ideal in the neoadjuvant setting. The role of systemic therapy in localized disease is currently undefined, but may benefit some subsets of patients with high-risk disease. For each patient, the utility and sequence of therapy should be discussed in a multidisciplinary conference at a sarcoma referral center. Recurrence is a significant risk in patients with WD/DD liposarcoma, especially those with retroperitoneal tumors and DD liposarcoma. Surveillance with serial cross-sectional imaging is important and should be personalized based on each patient’s risk and anticipated pattern of recurrence. When recurrence develops, although surgery is an option, the appropriate candidates must be carefully selected. Multimodality therapy is frequently used in these situations. Overall, DD liposarcoma has an approximately 20% to 30% rate of distant metastasis. For patients with unresectable and distant metastatic disease, systemic therapy options include chemotherapy and targeted therapies. Several newer drugs including immunotherapy are under investigation. This chapter will focus on DD liposarcoma within the context of WD/DD disease. We highlight the differences that arise with the presence of DD liposarcoma, especially how this may impact decision-making and management. We then conclude with additional pearls and pitfalls, along with a discussion of active issues for further investigation. 126ESTIMATED INCIDENCE PER YEAR, GENDER, AND RACE WD/DD disease represents one subset of liposarcoma, which is itself just one of over 50 to 70 different histologic subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma that together constitute only 1% of all cancers in adults.1–3 WD/DD liposarcoma is clearly very rare, and to our knowledge, there are no estimates of incidence specific to this disease. WD/DD liposarcoma occurs almost exclusively in middle-aged and elderly adults; in fact, the disease is exceedingly rare in infants, children, and adolescents. There is no gender or race predilection. Furthermore, there are no known risk factors for development of WD/DD liposarcoma, either social or environmental. Although this is a malignancy of fat, there are no clear associations with obesity or high-fat diet. Second primary cancers have been reported in WD/DD liposarcoma4; however, there are currently no defined genetic syndromes that predispose to disease development. DD disease tends to occur more frequently at the initial disease presentation (90%), but can also be observed later at recurrence (10%) in previously entirely WD disease. MOST COMMON PRESENTING SYMPTOMS WD/DD liposarcoma can occur in any location of the body, and as a result, presenting symptoms may vary. Overall, for most patients, the symptoms are vague and nonspecific. In the retroperitoneum, patients may have abdominal fullness, back pain, early satiety, reflux, or constipation. Unless there is specific nerve impingement (e.g., femoral), pain is otherwise generally mild, chronic, and tolerated. Giant retroperitoneal tumors can impede venous return, causing lower extremity edema in some patients, but this may not occur if collaterals (e.g., in the abdominal wall) have formed. Bowel and biliary obstruction is quite rare for retroperitoneal tumors. In all body locations, a mass lesion may be felt on physical examination. Alternatively, some patients may be completely asymptomatic, with their tumors discovered only after imaging done for another purpose (e.g., kidney stones). Tumors with dedifferentiation can be more locally aggressive compared to entirely WD tumors, but there is no clear association between presence of DD disease and higher frequency of symptoms. A small proportion of patients affected with WD/DD liposarcoma in the retroperitoneum and pelvis may present with systemic symptoms such as fever, elevated white blood cell count, hypoglycemia, or elevated transaminases. These symptoms may mandate expedited treatment (e.g., surgery), as patients may deteriorate very quickly. DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH Accurate diagnosis of WD/DD liposarcoma includes high-quality, contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging. In the extremity and trunk, this usually consists of MRI, whereas in the abdomen or retroperitoneum, CT is the most common imaging modality. WD liposarcoma is typically seen as a well-defined lipomatous mass with thickened internal fibrous septa.5 Presence of DD disease is suspected within a lipomatous tumor when there are focal, nonlipomatous (soft tissue density) areas. Suspicion is higher when these areas are well defined, have vascular contrast enhancement, or have central necrosis.6,7 Interestingly, DD tumors may also undergo osteogenic differentiation, which can be evident on imaging as focal intratumoral calcification. Overall, with characteristic features, cross-sectional imaging can almost be diagnostic, especially for tumors seen in the retroperitoneum. However, there are pitfalls, and expertise from a radiologist familiar with the disease is critical. Cross-sectional imaging is also critical for surgical planning purposes. A high-quality imaging study is necessary to adequately plan the surgical approach and anticipate possible complications. Therefore, if the quality of initial studies is poor, repeating the studies for better quality is warranted. Moreover, for patients with suspected or confirmed DD disease, staging should be done with a contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, as the lungs are the most common site of metastatic disease. The role of PET remains to be determined. WD tumors do not have metabolic activity on PET scan. Some, but not all, DD tumors have metabolic activity, but whether this correlates with disease aggressiveness is currently under investigation. Ultimately, to establish a diagnosis, the gold standard is histologic examination of the tumor tissue. In the preoperative setting, tissue is most commonly obtained through core-needle biopsy. Image (e.g., CT) guidance is recommended and the standard technique is coaxial (one pass of the sheath up to the periphery of the tumor, followed by multiple needle passes through the sheath and sampling of different tumor areas), for which the risk of tumor seeding is minimal.8,9 With core-needle biopsy, the diagnosis of 127WD/DD liposarcoma can typically be made; however, studies have shown relatively low accuracy for the specific diagnosis of DD disease.10,11 Incisional biopsy is not recommended for WD/DD liposarcoma because it may sample the wrong portion of tumor (without image guidance, e.g., for DD disease) and also disrupt the natural tissue planes, potentially making subsequent surgery more challenging. Microscopically, WD liposarcoma is characterized by atypical-appearing adipocytes of varying sizes separated by fibrous stroma with the sparse presence of cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. In tumors with DD, an abrupt transition from WD liposarcoma (low grade) to a nonlipogenic (most often, high-grade) sarcoma is seen (Figure 9.1). The morphology of the DD component can frequently overlap with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma or less frequently with high-grade myxofibrosarcoma. Historically, the original definition of dedifferentiation by Evans in 1979 included the abrupt WD transition and within the nonlipogenic component, five or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields (with fewer mitoses being called “cellular” WD disease).12 To date, Evans’ criteria for dedifferentiation are still used, but not universally adopted. It is also now well recognized that the WD to DD transition can actually be more gradual and, in some cases, low-grade and high-grade areas can even appear to be comingled. FIGURE 9.1 Microscopic appearance of liposarcoma with a dedifferentiated component. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin image. The abrupt transition to high-grade disease is clearly shown. (B) Immunohistochemistry demonstrating the expression of MDM2 (brown). Inset showing fluorescence in situ hybridization, positive for MDM2 amplification. DD, dedifferentiated; WD, well differentiated. “Low-grade dedifferentiation” has been used to describe the presence of fascicles of bland spindle cells with a cellularity somewhat intermediate between sclerosing WD liposarcoma and the typical high-grade areas. This, in part, overlaps with the “cellular” variants of WD liposarcoma described by 128Evans.13–15 Low-grade DD areas can feature variable morphologic features somewhat mimicking desmoid fibromatosis, solitary fibrous tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and even inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Dedifferentiation can have additional fascinating morphologic features. Heterologous differentiation can be observed in about 5% to 10% of cases, most often myogenic but also osteo- and chondrogenic. This can even be lipogenic in nature (so-called “homologous” dedifferentiation), overlapping morphologically with pleomorphic liposarcoma.16 Another very peculiar morphologic presentation of DD disease is represented by the presence of whorls of spindle cells mimicking neural or meningothelial structures.17 Very rarely, an intense inflammatory infiltrate is observed to the extent that it may obscure the lipogenic nature of the neoplasm. While dedifferentiation in itself is considered high grade, recent work has shown that application of the three-tier French (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer; FNCLCC) grading system used for soft tissue sarcomas, in general, can be useful to further stratify DD disease in terms of prognosis.18 Furthermore, data support the association of myogenic differentiation (particularly, rhabdomyoblastic) with remarkably poorer prognosis.18,19 The hallmark molecular aberration and pathognomonic genetic feature of WD/DD liposarcoma is chromosomal amplification at 12q13–15. This amplicon includes several key genes including MDM2 and CDK4. In addition to the microscopic appearance on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, interpreted by an experienced sarcoma pathologist, demonstration of MDM2 gene amplification by FISH contributes greatly to increased diagnostic accuracy (Figure 9.1). Immunohistochemically, as a result of 12q amplification, DD disease overexpresses both MDM2 and CDK4 in both lipogenic and nonlipogenic components.20,21 The demonstration of MDM2 nuclear overexpression is of great diagnostic support (Figure 9.1). In our experience, MDM2 immunohistochemistry exhibits high concordance with FISH analysis of MDM2 gene status. Co-amplification of c-JUN (mapping at 1p32) and of its activating kinase (mapping at 6q23) is also observed.22 In fact, it has been suggested that the activation of the c-JUN pathway may be involved in tumor progression from WD to DD liposarcoma; however, this is debated. Recent work has also identified a number of other genetic changes that may support WD to DD progression.23 GENERAL THERAPEUTIC APPROACH WD/DD liposarcoma can occur anywhere in the body, including the extremities, trunk, head and neck, and retroperitoneum. In the latter case, tumors can reach very large sizes (average 20–30 cm), and in fact, retroperitoneal liposarcomas are likely the largest cancers in the human body. Importantly, tumors with presence of dedifferentiation are also more common in the retroperitoneum, whereas dedifferentiation is quite rare elsewhere in the body. For WD/DD liposarcoma of any location in the body, surgery is the mainstay of treatment in patients with localized disease. Particularly in the retroperitoneum, where the tumors are larger and can abut or invade critical organs and structures (e.g., major vessels), expertise from a surgical oncologist with experience in this disease is critical.24 For retroperitoneal WD/DD liposarcoma, the goal of surgery is macroscopically complete resection with a single specimen encompassing the tumor and the involved contiguous organs, while attempting to minimize microscopically positive margins.25 In some cases, resection of adjacent organs or structures even without obvious involvement is necessary.26,27 Preservation of organs or structures should be made on a case-by-case basis, balancing disease biology and potential for local control versus potential morbidity and dysfunction. In general, tumors with dedifferentiation tend to be locally more invasive, and therefore, multiorgan resection (e.g., kidney, colon) may be anticipated in these cases compared to tumors that are WD only. Except in unique cases of palliative resection,28 there is no role for piecemeal or grossly incomplete (debulking) resection. Importantly, resections for retroperitoneal WD/DD liposarcoma can be major operations and patients should be optimized medically (e.g., comorbid conditions) before surgery. Specifically, in many patients, moderate to severe malnutrition may be present. There is some evidence, in fact, that malnutrition is generally underestimated and these patients have more postoperative complications and longer hospitalization.29 Surgical expertise and clinical judgment is also important for WD/DD liposarcoma of the extremities, trunk, and head/neck area, where there are arguably less well defined guidelines. If wide margins can be obtained, this is ideal, similar to many other subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma. There is, however, evidence to support that marginal complete resection may be adequate for these tumors in these nonretroperitoneal locations, which are mostly WD.30–32 129For patients with WD/DD liposarcoma, even after complete resection, there remains the risk for recurrence. This risk varies, but is definitely higher for tumors in the retroperitoneum and those with dedifferentiation.33 As an example, the 5-year locoregional recurrence rates range from 20% to 30% for extremity and trunk (mostly WD) to up to 50% to 60% for retroperitoneum (WD/DD disease).30,34–36 Other clinicopathologic factors also impact the risk of locoregional recurrence, including age, tumor size up to a certain extent, and multifocality (more than one tumor), the latter of which can also occur in some patients at the initial disease presentation.37–39 In an attempt to optimize local control, radiation therapy may be of benefit; however, this is considered controversial in WD/DD liposarcoma. In the retroperitoneum, if radiation therapy is given, attempts should be made to minimize toxicity to the bowel. Delivery is, therefore, ideal in the neoadjuvant setting with the tumor in place to act as a natural “spacer,” displacing the bowel. In the context of the broader group of all retroperitoneal sarcomas, several retrospective studies have shown that, indeed, radiation therapy improves local control compared to surgery alone.40–43 Recently, a multi-institutional retrospective study specifically focused on retroperitoneal liposarcoma, finding that across all histologic subtypes (WD vs. DD liposarcoma) and grades within DD disease, radiation therapy significantly reduced local recurrence rates on univariate analysis; however, this benefit was lost in all subgroups after multivariate analysis.44 A recent prospective clinical trial (EORTC 62092-22092 or STRASS)45 did not seem to support the benefit of radiation therapy for retroperitoneal sarcomas in general; however, further subanalysis by histologic subtype is still pending. Few data are available to define the benefit of radiation therapy for local control in the extremity and trunk. Without the constraints of adjacent viscera, delivery of radiation therapy may occur in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting, similar to other soft tissue sarcomas. One single-institution study showed that in extremity and truncal WD disease, there was significant reduction in 5-year local recurrence-free survival rate with the addition of adjuvant radiation therapy (98% vs. 80%); however, the authors highlighted potential disadvantages, including making subsequent surgery more challenging, and ultimately concluded that the decision should be personalized to each case.46 Given the rarity of DD disease in non-retroperitoneal sites, there have been no studies exploring the benefit of radiation therapy in this specific situation to date. The role of systemic therapy (e.g., chemotherapy) in either the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting for localized WD/DD liposarcoma is currently undefined. There is likely no benefit in patients with WD-only disease; however, there may be benefit of chemotherapy with doxorubicin plus ifosfamide (or dacarbazine if renal dysfunction) for patients with DD disease. Multi-institutional data for retroperitoneal sarcoma suggest that patients with FNCLCC grade 3 DD tumor have a distant metastatic rate of 33% at 5 years after complete resection, which is approximately threefold higher than that seen in patients with grade 2 DD disease.35 Given the complexity of retroperitoneal surgery and potential for complications, which can delay receipt of systemic therapy in the adjuvant setting, most sarcoma centers prefer to administer drug treatment in the neoadjuvant setting to these patients; however, this remains to be formally studied. Overall, the utility and sequence of therapy for each patient with WD/DD liposarcoma should be discussed within a multidisciplinary conference at a sarcoma referral center. The vast majority of patients with primary, localized disease will have first-line surgery and this may be the only therapy needed. This is particularly true for patients with nonretroperitoneal (extremity, trunk, head/neck) tumors and those with WD disease only (no evidence of DD disease). Alternatively, in patients with retroperitoneal tumors and those with DD disease, as discussed, some may benefit from multimodality treatment including neoadjuvant radiation therapy and systemic therapy, either before or after surgery. Neoadjuvant therapy (radiation and/or chemotherapy) may facilitate resectability in borderline cases, especially if tumor shrinkage can be achieved; however, to date, no studies have quantitated this potential benefit. RECOMMENDED FOLLOW-UP Given the risk of recurrence, close surveillance is important in patients with WD/DD liposarcoma. Although consensus recommendations (National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN], European Society of Medical Oncology [ESMO]) exist for surveillance in soft tissue sarcomas in general, there are no validated guidelines specific for WD/DD liposarcoma. For retroperitoneal tumors, along with history and physical examination, most sarcoma centers recommend initial contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis at 3 to 4 months after surgery to serve as a postoperative baseline. Repeat imaging should then be done every 4 to 6 months for at least 2 to 3 years and up to 5 years.47 For nonretroperitoneal 130body locations (extremity, trunk, head/neck), a similar schedule of interval imaging should be followed with contrast-enhanced MRI. For superficial tumors, ultimately, MRI may be replaced with ultrasound scans. In patients with DD disease, chest CT should be added. Surveillance should be modified based on personalized risk and the anticipated pattern of recurrence. Late recurrences can occur, particularly in DD liposarcoma.30,36 In support of this concept, in the multi-institutional retroperitoneal sarcoma studies, the curves for recurrence do not plateau even up to 8 years after resection.35 When recurrence develops (e.g., detected by surveillance imaging), decision-making and overall management can be complex and multimodality therapy is frequently used. Surgery is always an option and is ultimately performed in most patients. In fact, many patients with WD/DD liposarcoma, particularly retroperitoneal, will have multiple resections during their lifetime.48 An important consideration is that re-resection is often more challenging in comparison to surgery for primary disease owing to scar tissue and distorted tissue planes. Candidates for surgery must, therefore, be carefully selected. One study described a “1 cm per month” rule in which patients with at least this rate of tumor growth on imaging had poor outcomes and would be less likely to benefit from surgery.49 For patients who are asymptomatic, indeed, a period of observation may be warranted, not only to assess the rate of growth but also to better understand the disease biology, as in some cases, multifocal disease may soon be evident on subsequent imaging.37,50–52 Interestingly, there may also be a subset of patients (mostly with WD disease) who may remain stable over a prolonged period without any treatment.53 Currently, there are no laboratory tests that are useful to detect recurrence in WD/DD liposarcoma, although this is an area under investigation (e.g., serum biomarkers).54 Patients with retroperitoneal tumors who have had nephrectomy as part of their surgery should have residual kidney function checked and optimized as needed prior to contrast administration done for their imaging. PROPENSITY TO METASTASIZE DD liposarcoma has a low/intermediate propensity to metastasize. The overall frequency is approximately 20% to 30%, and the common site of distant metastasis is the lungs. As discussed, however, there are likely subsets within DD liposarcoma (e.g., FNCLCC grade 3 or rhabdomyoblastic differentiation) with a higher metastatic propensity, and in some patients, extrapulmonary sites of distant disease (e.g., liver, bone) may also be seen. In contrast, entirely WD tumors do not metastasize. WD/DD liposarcoma never metastasizes to the locoregional lymph nodes. THERAPEUTIC APPROACH FOR METASTATIC DISEASE Treatment options for patients with unresectable and metastatic disease are limited. In soft tissue sarcoma in general, frontline treatment for unresectable/metastatic disease is usually systemic therapy with doxorubicin, alone or in combination with ifosfamide, with a reported objective response rate (ORR) in the range of 20% to 40%.55 The combination of doxorubicin and ifosfamide is superior to doxorubicin alone in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and results in a doubling of ORR (26% vs. 14%), but with a trend toward an overall survival (OS) benefit.56 Therefore, this combination regimen is often used, for example, in symptomatic patients who need tumor shrinkage or in an attempt to facilitate resectability. In contrast, a single-agent regimen can be used in a patient with multiorgan metastasis and poor performance status, with the goal of fewer chemotherapy-related side effects. In WD/DD liposarcoma specifically, the ORR reported for anthracycline-based chemotherapy is lower, and therefore, traditionally, this is considered to be a poorly chemosensitive subtype of soft tissue sarcoma.57 As an example, in a retrospective multicenter analysis, the ORR was 12%.58 More recent single-institution data for WD/DD liposarcoma, however, suggests that the ORR may be higher (up to 21%), especially with combination chemotherapy regimens.59 It is important to note that treatment is usually given for DD tumors; there are currently no systemic therapies with demonstrated efficacy in WD-only tumors. At this point, for WD/DD liposarcoma, the first-line treatment remains doxorubicin with or without ifosfamide. In second-line systemic therapy, gemcitabine and docetaxel (Taxotere) are often used.59 Approved drugs for second, third, and further lines of treatment include trabectedin, high-dose (single agent 14 g/m2) ifosfamide, and eribulin. After the first-line treatment, the best further line treatment is not established, and of course, performance status and patient preference are included in the decision-making process. Trabectedin represents a valid second-line treatment for WD/DD liposarcoma, although the ORR of this drug does not exceed 10%.60 Interestingly, there are reports of greater activity of trabectedin in a 131subset of “low-grade” DD liposarcoma. One advantage of this drug is that it is well tolerated without cumulative toxicity. In fact, it has been reported that several patients have been treated for >1 year with trabectedin.60 Continuous infusion, high-dose ifosfamide (ciHDIFX) is another treatment option. In a retrospective series of advanced WD/DD liposarcoma patients treated with ciHDIFX, the ORR was 26% with an additional 50% of patients achieving disease stabilization.61 All partial responses in this series occurred in patients with a “high-grade” DD component. Compared with the classic schedule, high-dose (12–14 g/m2) ifosfamide is given via a portable external device over 14 days with good tolerability. At these dose levels, ifosfamide can be active in patients already exposed to standard dose in combination with doxorubicin.62–64 Eribulin was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency as a third-line treatment in liposarcoma. This was based on results from a randomized Phase 3 study comparing eribulin to dacarbazine in advanced liposarcoma and leiomyosarcoma.65 Although there was no difference in median PFS between the two groups (2.6 vs. 2.6 months, p = .23), eribulin demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in OS (13.5 vs. 11.5 months, p = .0169). Tumor responses, however, were limited to just two patients. Subgroup analyses suggested that liposarcoma patients benefited the most, with the median OS being 15.6 versus 8.4 months in those who received eribulin versus dacarbazine. Importantly, this benefit was observed irrespective of the liposarcoma subtype (e.g., 18.0 vs. 8.1 months, hazard ratio [HR]: 0.43 in DD liposarcoma).66 As discussed in the section “Diagnostic Approach,” WD/DD liposarcoma has a distinct genetic signature characterized by amplification of several notable genes including MDM2 and CDK4. Recently, several targeted therapies directed at MDM2 or CDK4 have been developed. In the clinical studies conducted so far,67,68 however, activity has been limited. Disease stabilization is noted in some patients (in some cases, it is prolonged), but tumor response (ORR) is rarely seen. Among the newer drugs, another targeted therapy under investigation in DD liposarcoma is selinexor, an inhibitor of exportin 1 (XPO1), which is involved in the movement of cargo proteins from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. These proteins include the tumor suppressor proteins, which can be inactivated through nuclear exclusion in the presence of XPO1 overactivity. After promising Phase 1b study results showing improved PFS,69 a randomized double-blind study versus placebo is now ongoing in the United States and Europe (NCT0260646). Immune checkpoint inhibitors are not yet the standard treatment in soft tissue sarcoma in general, but several trials are currently ongoing. Specific to DD liposarcoma, the SARC028 trial showed that two of 10 patients treated with pembrolizumab (anti-PD1) showed a partial response (ORR 20%) with a median follow-up period (across all soft tissue sarcoma patients) of 14.5 months.70 Additional expansion cohort studies for DD and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (another histologic subtype with tumor response) are ongoing. SUMMARY DD liposarcoma can be considered a part of a spectrum of diseases that include WD liposarcoma and, in fact, the two counterparts are often found within the same tumor. Compared to a tumor that is entirely WD, the presence of dedifferentiation changes the disease biology, making it clinically more aggressive and conferring metastatic potential. WD/DD liposarcoma can occur anywhere in the body, but DD disease is more common in the retroperitoneum, where tumors are also larger and surgery is more challenging. As a result, DD disease should be viewed from a different perspective on many levels in comparison to WD-only disease. Several active issues remain. From a disease biology standpoint, the basis for development of dedifferentiation is currently elusive. Is DD disease truly clonally derived from WD disease and what leads to this transformation? Is this transformation intrinsic to the tumor cell or perhaps related to the microenvironment? For the latter, work has been done describing a unique intratumoral immune response in WD/DD liposarcoma, which has set forth hypotheses to be tested.71–73 Another unresolved issue is the importance of DD content within a tumor: Are there clinical differences between a microscopic versus macroscopic focus and how do we manage an entirely DD tumor (no evidence of WD disease)? Ultimately, understanding DD development is disease-defining and has significant clinical implications. Given the importance of recognizing dedifferentiation and the impact on subsequent decision-making and management, the pretreatment diagnosis of DD disease needs to be optimized. As discussed in the section “Diagnostic Approach,” the accuracy of core-needle biopsy for diagnosis of DD disease 132is relatively low, even with standard image guidance.10 The utility of PET to discern DD disease and specifically identify high-risk disease is being studied. Evaluation of other imaging modalities (e.g., radiomics) is warranted, and in the future, perhaps a serum biomarker will be found that marks the presence of DD disease (vs. WD-only disease). Greater clarity is also needed with the pathologic diagnosis of DD disease. First, the criteria for diagnosis (FNCLCC vs. Evans) should be unified. This would facilitate research studies and broaden the applicability of study findings to more patients. Second, clearly within DD disease, there is also a spectrum of disease aggressiveness. Although data exist that rhabdomyoblastic differentiation and FNCLCC grade 3 disease are associated with a higher metastatic potential,19,35 are there other subsets of DD disease with clinical significance that remain to be identified? With regard to treatment for localized disease, as discussed in the section “General Therapeutic Approach,” the true benefit of nonsurgical treatments (radiation and systemic therapy) deserves further study. For radiation therapy, ongoing subgroup analysis of the completed, prospective STRASS trial may hopefully define the subset of patients for whom treatment improves local control. For systemic therapy, the potential for durable locoregional and distant disease remains to be determined. Similar to radiation therapy, the benefit of systemic therapy over surgery alone in patients with localized disease may only be limited to a subset of patients. For patients with unresectable and metastatic disease, while there are, indeed, several systemic therapy options available, the challenge remains in identifying the appropriate option for the goal of treatment (e.g., rapid tumor shrinkage vs. prolonged disease stabilization), while balancing toxicity. Disease-specific combination therapies with potential synergistic effect in WD/DD liposarcoma should also be explored. After systemic treatment, do select patients benefit from resection, perhaps even metastasectomy, for limited sites of disease? It is hopeful that all of these active issues with WD/DD liposarcoma—from disease biology to clinical—can be addressed through further investigation, ideally through collaborative research among sarcoma centers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree