- The birth incidence of cystic fibrosis (CF) is about 1 in 2500 newborns, and the carrier rate in the population is about 1 in 20 among persons of Caucasian descent, making CF the most common inherited life-shortening disease in many populations.

- The aetiology of malnutrition is complex and arises as a result of the energy imbalance caused by a combination of decreased energy intake, increased energy needs, and increased energy losses.

- Nutritional status is strongly associated with pulmonary function and survival.

- Maintenance of growth patterns as near normal as possible in children and nutritional support in adults, particularly during infection and other adverse complications, are major goals of multidisciplinary care, and along with the physician, nurse, and physiotherapist, the dietitian is one of the key members of the management team.

- Many other complications of CF may require specific nutritional intervention, including diabetes, liver disease, and osteoporosis. Fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies should be anticipated and prevented.

24.1 Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) was first identified in the 1930s as an important cause of failure to thrive, malabsorption of fat, fat-soluble vitamin deficiency, and severe, recurrent, or persistent lung infection in young infants. Affected babies rarely survived beyond a year or two. Autopsy revealed fibrosis and cysts in the pancreas, hence the name. Increasing recognition, improved survival, and greater awareness of the many clinical features which may occur in CF have led to our current understanding of its genetics and pathophysiology, and to realistic hope of new treatments which will control, if not cure, CF in the foreseeable future.

In the twenty-first century, CF is a rare cause of death in infants and young children, and mean survival in western Europe and North America now approaches 40 years (see Box 24.1). In general, survival correlates well with nutritional status, although by far the most important immediate cause of death remains lung damage consequent on chronic infection. The interaction between nutrition and lung function is complex and will be referred to throughout this chapter, but at all ages there are challenges to nutritional management. Maintenance of growth patterns as near normal as possible in children and nutritional support in adults, particularly during infection and other adverse complications, are central to the prognosis, and along with the physician, nurse, and physiotherapist, the dietitian is one of the key persons in the management team.

24.2 Definition and pathology

CF occurs as a consequence of mutations in a single gene, which codes for the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator protein (CFTR), a channel which conveys chloride ions through the cell membrane of epithelial cells, notably in the lungs, intestine, and pancreatic ducts. Impaired transport function of the CFTR channel explains the clinical features of the disease. Both parents of an affected child must pass on a mutated copy of the gene to their offspring: possession of only one mutation makes an individual, like the parents of a CF child, a healthy carrier (heterozygote). The incidence of CF and the predominant specific mutations of the CFTR gene vary between populations. More than 1000 different mutations have been identified, most of them very rare and some affecting only one family. In the UK the single commonest mutation, about 70% or more of the total, is known as F508del. The birth incidence of CF is about 1 in 2500 newborns, and the carrier rate in the population is about 1 in 20 among persons of Caucasian descent, making CF the most common inherited life-shortening disease. In other populations, notably in Eastern Asia, it is much less common (Table 24.1).

- Improved nutritional status at all ages, but particularly in childhood.

- Improved antibiotic treatment.

- Survival of infants with meconium ileus, once usually fatal.

- Early diagnosis.

- Better physiotherapy techniques.

- Frequent surveillance and treatment in specialist CF clinics.

- New modalities of treatment, such as lung transplantation.

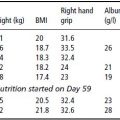

Table 24.1 Estimated frequency of CF at birth in different populations.

| National group | Birth incidence |

| UK | 1/2500 |

| USA (white) | 1/3500 |

| USA (African American) | 1/14 000 |

| USA (Asian) | 1/25 500 |

| Sweden | 1/7700 |

| The Netherlands | 1/3600 |

| Ireland | 1/1500 |

| Finland | 1/25 000 |

| Israel | 1/3300 |

| Japan | 1/323 000 |

| Faroe Islands | 1/1800 |

The CFTR channel regulates the passage of chloride through the cell membrane of secretory and absorptive epithelia. Dysfunction of CFTR results in an altered electrolyte and fluid composition of secretions, which are often dehydrated and sticky: an early name for CF, still used in some countries, was mucoviscidosis. Characteristic (but not necessarily unique) pathological features are found in the pancreas, lungs, liver, intestines, and vas deferens, among affected organs, and can superficially be attributed to blockage of small ducts by sticky secretions. Important among affected secretions is sweat, and elevated chloride content of a carefully performed standardised sweat test is the usual diagnostic criterion for CF. This is now usually confirmed by genetic analysis of DNA.

24.3 Clinical features

The clinical features of CF include intestinal obstruction with inspissated meconium in about 15% of affected newborns (meconium ileus); failure to thrive in infancy secondary to malabsorption caused by pancreatic insufficiency; repeated and eventually chronic infective and structural lung disease (bronchiectasis); atresia of the vas deferens, producing infertility in almost all CF males; and excessive salt loss in the sweat, leading to heat intolerance in warm climates or heat waves.

It is the lung disease which is the usual cause of death. Both the respiratory and the nutritional status have an effect on survival, and they are surprisingly closely associated. While progressive lung disease makes extra nutritional demands on CF patients, it may also limit their ability to increase their energy intake. Other, less constant but common clinical features of CF, which affect the patient’s nutritional needs, include liver disease, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes mellitus (CFRD) and osteoporosis. The main clinical features of CF are summarised in Box 24.2.

Respiratory features

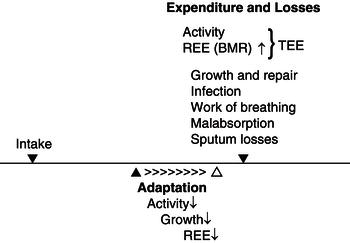

The lungs are apparently normal at birth, but in undiagnosed and untreated infants they often become infected within the first few weeks, and may go on to become seriously damaged by infection and chronic inflammation. This is the rationale for newborn screening programmes, which allow early diagnosis, with prevention and treatment of infection particularly important during this critical phase. The lungs are still growing in complexity during the first 2 years, and structural damage at this stage will affect lung capacity throughout life. When lung disease is established, as it is eventually in most CF patients, chronic bronchopulmonary inflammation with superimposed periods of acute infection carries an increased energy requirement, but achieving an adequate intake is hindered by breathlessness and poor appetite. Repeated coughing can cause vomiting, and large meals exacerbate shortness of breath: patients always give priority to breathing over eating. Inflamed bronchi may bleed, particularly during episodes of coughing, and frequent loss of small or large amounts of blood can lead to iron-deficiency anaemia. Most patients have chronic sinus disease, which often impairs the senses of taste and smell, which are important to appetite. Figure 24.1 illustrates how respiratory and gastrointestinal factors combine to increase energy requirements, which will produce a negative energy balance if they are not met by a correspondingly enhanced intake.

- gastroesophageal reflux;

- pancreatitis;

- pancreatic insufficiency;

- maldigestion;

- malabsorption;

- meconium ileus (newborn infants);

- distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS);

- cholelithiasis;

- cirrhosis;

- portal hypertension;

- splenomegaly;

- fibrosing colonopathy;

- rectal prolapse.

- bronchiectasis (characteristic infective organisms include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staph. aureus, H. influenzae, Burkholderia cepacia, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia);

- bronchitis;

- pneumonia;

- atelectasis;

- pneumothorax;

- haemoptysis;

- sinus disease.

- male infertility due to atresia of the vas deferens;

- CFRD;

- osteoporosis, osteopaenia.

Figure 24.1 Energy balance in CF. REE, resting energy expenditure; BMR, basal metabolic rate; TEE, total energy expenditure. Adapted from Dodge & O’Rawe (1994).

Gastrointestinal features

Pancreatic insufficiency

This is the major gastrointestinal clinical feature of CF. It results from pancreatic damage resembling chronic pancreatitis, which is usually well established even before birth. Pancreatic insufficiency occurs when more than 95% of the structure or functional capacity of the exocrine pancreas has been lost. Although some degree of pancreatic abnormality is almost universal in CF, the proportion of patients who are pancreatic insufficient (PI) varies between different populations, largely according to their particular genetic mutations. Those who retain adequate pancreatic function for normal digestion are called pancreatic sufficient (PS). In northern Europe, more than 85% of CF patients are PI, but in Mediterranean countries 60% or even more may be PS. Because slow destruction of the pancreas may continue for many years, a person who is PS in early life may become PI later, and thus require pancreatic enzyme supplements.

Pancreatic insufficiency causes maldigestion and malabsorption of macronutrients, particularly fat and protein. Fat malabsorption (steatorrhoea) makes stools bulky and greasy (in severe cases resembling melted butter), floating in water and difficult to flush. Protein malabsorption makes the stools offensive. Other symptoms include flatulence, bloating, and abdominal discomfort. Stool losses of energy – rich fat, along with less energy-dense but nutritionally essential protein – retard the growth of children and impair their ability to resist infection. Fat malabsorption is often accompanied by poor absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. In addition to pancreatic insufficiency causing maldigestion, there is a variable impairment of absorption of the products of intestinal fat digestion, such as glycerol and fatty acids, in the intestine itself, which is well documented but not completely understood. Reduced secretion of bile acids via the liver and biliary system plays a part, by limiting emulsification of lipids and reducing the surface available for attachment of pancreatic lipase.

Several direct and indirect tests are available to assess pancreatic function. Direct tests measuring enzymes and electrolytes in pancreatic secretions, following standardised stimulation, are highly specific but both invasive and occasionally dangerous, and are therefore precluded from routine use. Indirect tests include 72-hour faecal fat analysis, ideally with a known fat intake so that a coefficient of fat absorption (CFA) can be calculated. This is often referred to as a ‘gold standard’ test, but in practice it is not specific for pancreatic disease and not reproducible, and it is understandably unpopular with patients and laboratory staff. Recent studies have shown that although the CFA is much more consistent in healthy controls, results may vary by up to 40% when repeatedly performed in the same CF patient under identical conditions. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of pancreatic elastase 1 in stool is useful as a sensitive and specific marker of pancreatic insufficiency, and thus for confirming whether a patient is PS or PI. It is of no value in monitoring efficacy of treatment, for which the CFA has been widely used. If the child patient is growing at a normal velocity, and the adult maintaining body weight and nutritional status, there is no need to perform repeated CFA, particularly in view of its poor reproducibility.

Serum levels of immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) are elevated in virtually all newborns with CF, whether they are subsequently PI or PS, indicating that at birth some degree of pancreatic function is present but that enzymes are leaking from the pancreas into the circulation. In PI babies, the IRT levels fall to subnormal or undetectable over the first weeks or months, and these low levels are an indirect confirmation of inadequate pancreatic resources. A raised IRT level in a blood spot is the basis of newborn screening programmes for CF in Europe, North America, and Australasia.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is treated with oral pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), which must be taken with all meals and snacks, apart from sugary drinks.

Pancreatitis

Acute attacks of pancreatitis may occur in PS patients, and occasionally in those regarded as PI but in whom some residual pancreatic function must remain. Pancreatitis is more common in adults than in children. Coexisting gallstones can confuse the diagnosis. Slowly progressive chronic pancreatitis is the basis of PS patients becoming PI.

Meconium ileus

This is the name given to a serious condition which affects about 15% of CF newborn infants. They present with a distended abdomen and fail to pass meconium. The colon is empty and contracted, but the small intestine proximal to the ileo-caecal valve is obstructed by thick, sticky meconium, and the small bowel has occasionally ruptured in utero, so that the meconium has spilled into the abdominal cavity. Uncomplicated cases can often be treated conservatively with an enema of gastrografin, a radio-opaque fluid with high osmolality, but resistant cases and those with meconium peritonitis need surgery. The convalescence is often stormy, but with modern management the great majority survive what was once a perilous presentation of CF. If extensive surgical resection is necessary, particularly if it includes the ileo-caecal valve, the child may be left with the problems of a short gut with uncertain motility, in addition to those of uncomplicated CF.

Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome

In older children and adults with CF, the distal small bowel and sometimes the proximal colon may become partially or completely obstructed by thick mucofaeculent material composed of sticky secretions and food residues. It may become so adherent to the intestinal mucosa that it cannot be removed without causing bleeding.

Contributory precipitating factors include inadequate PERT, sudden dietary changes, and dehydration. The onset may be abrupt or insidious, following a period of increasing constipation. The patient complains of abdominal cramps, pain, and distension, and a mass (which may be tender) is usually palpable in the lower-right quadrant of the abdomen. Surgeons unfamiliar with CF sometimes perform a laparotomy, suspecting an acute abdominal emergency such as appendicitis. DIOS can be treated with gastrografin, like meconium ileus, which can be given either by mouth or by enema, but the generally preferred treatment is large doses of a commercial bowel-preparation balanced electrolyte solution such as Golytely, given by mouth in the largest tolerable amounts. Following resolution, the patient must be given advice about diet, compliance with PERT, and avoidance of dehydration.

Fibrosing colonopathy

Fibrosing colonopathy (see Fitzsimmons et al., 1997) is a complication of overdosing of pancreatic enzymes, almost always in children. A similar condition with thickening of the ileum is sometimes seen in adults. It may present with watery or mucousy diarrhoea, occasionally bloodstained, which reflects colitis but may be wrongly interpreted as a need for even higher doses of PERT. The condition may be clinically reversible at the colitis stage, but can progress to narrowing and shortening of the colon, with signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction. The characteristic pathology is dense submucosal fibrosis. It must always be remembered that pancreatic enzymes are normally active in the upper small intestine, but in CF patients given PERT there is a considerable amount of potentially damaging (administered) digestive enzyme activity in the colon, and even in the stools. Fibrosing colonopathy has exceptionally been described in young (PS) CF infants who have never had PERT, following surgical intervention for meconium ileus, presumably caused by rapid transit of endogenous enzymes to the inappropriate location of the colon.

Liver disease

Some degree of fine increased biliary fibrosis is very common at autopsy in CF patients, but only about 5% have serious clinical liver disease (cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and liver failure), for reasons which are not well understood. No clear-cut genetic modifying factors have been identified which determine why it occurs in a minority of patients with common CFTR mutations. Once established, it sometimes progresses quite rapidly, out of proportion to coexisting CF lung disease. Occasionally mild obstructive jaundice occurs in young infants, apparently caused by cholestasis (‘biliary sludge’), and serum liver enzymes may be raised. This is usually transient and is not a predictor of later liver disease; nor is the enlarged fatty liver sometimes observed in toddlers, usually with other evidence of poor nutrition. Although its antecedents are uncertain, patients who are going to have major liver problems usually present with appropriate symptoms by their mid-teens, and the incidence of CF liver disease does not greatly increase with improving life expectancy.

The early stages of cholestatic liver disease may be detected through elevated liver enzymes – alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transferase – and can be reversed by treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid. Gallstones are commonly found in CF and may or may not be symptomatic. Biliary cirrhosis may follow, with portal hypertension ascites and end-stage liver failure. Liver transplants have been successfully performed in CF, including heroic procedures in which liver and bilateral lung transplants were performed in the same operation.

Patients with cirrhosis and hepatosplenomegaly often find eating difficult, as a consequence of a distended abdomen with elevation of the diaphragm.

Liver disease increases the likelihood of deficiencies of fat-soluble vitamins, particularly vitamins D and K. If enteral tube feeding is needed, the presence of oesophageal varices is not a contraindication to using fine-bore soft nasogastric tubes, but gastric varices preclude percutaneous gastrostomy placement.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) is common in CF. Contributory causes probably include an increased differential between abdominal and thoracic pressures as a result of ‘stiff’ lungs, postural drainage during physiotherapy, and abdominal distension from flatulence or enlarged liver and spleen. Reflux of acid gastric contents produces oesophagitis, with its complications of vomiting, heartburn, and aspiration into the lungs, which may complicate respiratory disease. Severe bouts of early-morning coughing in patients who had overnight nasogastric tube feeds may provoke reflux and regurgitation.

Oesophagitis is treated with drugs such as proton pump inhibitors, which inhibit acid secretion and allow the oesophageal mucosa to heal.

24.4 Malnutrition

The aetiology of malnutrition in CF is complex, but can be simplified as a combination of increased energy demands and energy losses in the presence of an often decreased dietary intake, giving rise to a negative energy balance (Figure 24.1).

The majority of patients are able to keep themselves in positive energy balance, but failure to do so results in malnutrition.

In children, malnutrition is best defined as a weight-for-height value below 90%. The corresponding definition for adults is a body mass index (BMI) below 20 kg/m2.

Dietary intake

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree