Chapter 32 Complementary and Alternative Therapies

BACKGROUND

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) can be defined as “those healthcare and medical practices that are not currently an integral part of conventional medicine”.1 Surveys on the use of CAM by HIV-infected individuals indicate that utilization of these modalities has been common from the start of the epidemic to the current era of potent antiretroviral therapy (ART).2–7 Prior to the availability of potent ART, CAM use was focused on treating HIV and improving the immune system. Currently, the most common reasons for using CAM are (1) to relieve symptoms due to HIV infection or medications, (2) increase one’s self of well-being, (3) enhance the immune system, (4) slow the progression of the disease, and (5) supplement allopathic medicine.8–10 The latter reason is important because most HIV patients who use CAM do so in conjunction with, rather than to replace, allopathic medicine. HIV patients who take CAM are most likely to (1) be more involved in the medical decision process, (2) have a negative attitude toward ART, (3) have had HIV for a longer period of time, (4) have progression in their disease, (5) have a higher income, (6) have a higher level of education, and (7) be a female.3,4,8,11

One of the largest surveys on CAM use by HIV patients is the Alternative Medicine Care Outcomes in AIDS (AMCOA) study which enrolled 1675 HIV patients between 1995 and 1997. Approximately 63% of the enrollees reported taking ART and 63% reported using 1600 different types of CAM. The most common modalities were prayer (58%), garlic (53%), massage therapy (49%), meditation (46%), and acupuncture (46%).2 More recent, smaller surveys in which at least 50% of HIV patients were on ART showed that 36-88% were on CAM.4–6 The most common modalities were vitamins, herbs, and prayer.

One of the major concerns about CAM use by HIV patients is that many clinicians are often not aware that their patients are using CAM. In one study, 33% of clinicians were not aware that their HIV-positive patients were using complementary modalities.3 More importantly, 25% of the patients were using CAM that had the potential for adverse effects. The two main reasons for this disconnect is the provider simply not asking and/or the patient not wanting to disclose this information for fear of losing the respect of the primary provider.

HIV care providers should be familiar with some of the common complementary and alternative agents in current use. Clinicians who care for HIV-infected individuals need to be familiar with these approaches for several reasons. First, approximately half of any HIV patient group uses them. Second, some treatments may interact with standard therapies in significant ways. Third, some CAM therapies have been shown to do harm, whereas others could conceivably show benefit. The line between standard and alternative therapy itself has blurred. When an alternative’s therapeutic value is documented it rapidly becomes standard therapy.12 Fourth, a symptom may be due to a CAM therapy and not the illness per se or from side effects of prescribed medications. Fifth, some “complementary” approaches such as nutrition, exercise, and stress reduction are logical adjuncts to therapy. Sixth, the clinician can be an important source of accurate and unbiased information on complementary therapies. Finally, since the care of the HIV patient is a long-term proposal, the physician–patient relationship is paramount. When patients see that their provider is interested in the healing approaches they are pursuing, trust and rapport deepens. There is still truth to an observation made several years earlier that “when healthcare providers take the time to get involved and learn about the panoply of alternative options, including the rationales for prescribing alternative treatments, their most frequent toxicities, and the reasons why patients are optimistic about their use; the resulting compassionate understanding, confidence, and trust could conceivably provide a significant therapeutic benefit itself for the individual with HIV infection”.13

THE NATIONAL CENTER FOR COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM).14 In 1995, the office granted its first funds to investigate alternative and complementary therapies for HIV infection. Bastyr University in Seattle, a naturopathic institution, received funding to become the center for HIV CAM studies. The university established a national database cohort of HIV-infected individuals using CAM therapies.2 They collected prevalence and follow-up information on outcome measures of patients employing a wide variety of alternative and complementary interventions. In addition, they provided seed funding to investigators conducting small pilot interventional trials in patients with HIV.

In 1998, the OAM was upgraded to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). The establishment of NCCAM allowed more funds to become available for the study of CAM therapies in HIV-positive patients. The Center has awarded a number of grants to investigate promising or widely used interventions. To access current NCCAM-funded HIV/CAM clinical trials, visit their website at http://nccam.nih.gov. The existence of this program reflects the acceptance that use of complementary therapies will continue in patients with HIV despite excellent viral suppression and immune restoration with antiretroviral agents.

The NCCAM provides a concrete framework for the discussion of CAM therapies. The Center has divided the interventions into five major domains (1) alternative medical systems; (2) mind-body interventions; (3) biologic-based therapies, e.g., herbs; (4) manipulative and body-based systems, e.g., massage; and (5) energy therapies, e.g., magnets.15 The NCCAM categorization provides a useful framework for review of available information that currently exists on the use of these various CAM interventions in the HIV population. Where data from controlled clinical trials is unavailable, a description of some widely used modalities in each category will be offered.

ALTERNATIVE MEDICAL SYSTEMS

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is a system of healing that has been developed over thousands of years. TCM in various forms is a medical system which HIV-infected individuals often incorporate into their treatment regimen primarily to treat symptoms (e.g., nausea, wasting, sleep disturbances, and pain) related to HIV infection or medications. Chinese medicine involves balancing the “energy” of the body by combining primarily acupuncture, herbs, diet, exercise with an emphasis on treating the whole person rather than the disease.16 Two individuals, each suffering from the same “disease” in Western terms, might receive very different Chinese diagnoses and medical treatments. Each individual has unique strengths, weaknesses, imbalances, and life-long patterns that affect how their body deals with HIV. The idea is to understand all of this and then effect changes in the underlying constitution of the individual by altering the flow of energy or Qi. TCM has been rather mysterious and ill-comprehended by Western healthcare practitioners until recently, when more have shown interest and received training in these approaches.

In spite of the highly individualized approach of Chinese medicine, standard clinical trials have been designed to test herbal formulations and acupuncture treatments in HIV. In one clinical trial, a 31-herb combination based on two preparations, Enhance and Clear Heat, was administered to patients with two or more HIV-related symptoms. Participants were randomized to receive either 28 pills of the Chinese herbal preparation or placebo daily for 12 weeks.17 No significant changes were seen in any of the major outcome variables studied. There was a greater change in median life satisfaction in the herbal group. Another subsequent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of standard Chinese herbs showed no difference in symptoms, quality-of-life, viral load or CD4 cell counts between the herb group and placebo group.18 The Chinese herb group had twice the frequency of gastrointestinal disturbances.

In several uncontrolled studies and anecdotal reports, formulas containing TCM ingredients such as astragalus, lingustrum, ginseng, licorice, and other Chinese herbs have shown some effectiveness against various symptoms such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, diarrhea, and skin rashes. In general, they did not appear to improve immune parameters or HIV viral load. In a pilot evaluation of a herbal formula called Source Qi, HIV patients with chronic pathogen-negative diarrhea experienced a modest, nonstatistically significant decrease in the average number of stools per day in each week of the 8-week open-label study.19 Surprisingly, patients who were receiving nelfinavir-based regimens fared slightly worse than patients on other protease inhibitors (PIs). It was postulated that the known nelfinavir side effect of diarrhea could have resulted from an increased nelfinavir effect overall, perhaps due to increased nelfinavir blood levels due to a herb–drug interaction. This underscores the need to obtain data on interactions of the most commonly used Chinese herbs with antiretroviral agents.

Acupuncture is commonly used by HIV patients for pain relief, especially pain due to peripheral neuropathy. Aware of the high use of acupuncture for painful neuropathy in patients refractory to analgesics, the Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS designed a factorial trial of a standard acupuncture regimen and amitriptyline.20 A total of 250 persons with HIV-related neuropathy were enrolled in the nationwide trial. There was no statistically significant difference between either of the two interventions and their placebo with regard to the effect on neuropathic pain. Because both the acupuncture intervention and the sham acupuncture produced similar relief from neuropathic pain, the investigators concluded that the acupuncture was ineffective. In truth, the sham acupuncture utilized involved insertion of needles into “alternate points” which one could argue had equal effectiveness with the experimental “true” points, making conclusions about the efficacy or lack of efficacy of acupuncture problematic. The fact that the study was conducted in the setting of a federally-funded HIV clinical trial groups, however, speaks for the viability of evaluating alternative therapies in the mainstream clinical research infrastructure.

MIND-BODY INTERVENTIONS

Among the large survey of 1016 participants in the AMCOA study, 56% reported utilizing prayer and 33% reported being involved in spiritual activity.2 Data from other surveys suggest that most patients have a spiritual life and regard their spiritual health as important as their physical health.21 A number of studies in HIV-uninfected patients have shown direct relationships between religious involvement, spirituality, and positive health outcomes such as mortality, physical and mental illness, quality of life, and coping.22 Prayer itself was shown to have a positive effect on outcome of patients in the coronary care unit (CCU).23 In this blinded controlled trial involving 393 subjects, hospitalized patients who were prayed for by prayer groups had superior outcomes compared to those who were not. However, another study of 799 coronary care patients failed to demonstrate a clinical benefit for intercessory prayer, although it differed from the earlier trial in that patients were randomized at the time of hospital discharge rather than during their CCU stay.24 An editorial accompanying the latter study states “the weakness of the study is that the effect explored has no basis within the current scientific paradigm. If found to be true, such an effect would indeed challenge our understanding of the universe and perhaps even overturn much accumulated scientific knowledge to date.”25

Despite some skepticism, a systematic review of available data from randomized trials of “distant healing” found that ∼57% of the 23 trials involving ∼3000 patients did show a positive treatment effect.26 Distant healing (DH) can be defined as “a conscious, dedicated act of mentation attempting to benefit another person’s physical or emotional well-being at a distance”.27 A randomized, double-blind trial of DH was conducted in 40 patients with advanced AIDS at the very beginning of the HAART era.27 Pair-matched subjects were assigned to either 10 weeks of DH or a control group. Healers included practitioners from Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, Native American and shamanic traditions as well as those practicing secular methods. Each subject in the DH group was treated by a total of ten different practitioners and each of the 40 practitioners treated a total of five patients. Baseline CD4 cell counts were less than 100/mm3 in both arms of the study. All patients were receiving Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) prophylaxis and nearly all were on PI containing antiretroviral regimens. At 6 months, a blinded chart review found that the treatment subjects had significantly fewer AIDS-defining illnesses and required less medical attention in the form of doctor visits and hospitalizations. Participants who had been in the treatment group also had significantly improved mood compared with controls. There was no effect on CD4 cell count. HIV viral load was not assessed.

A recently completed NCCAM funded study attempted to replicate these earlier findings. In this trial, 150 participants were randomized to being healed by a healer, a nurse who had been trained in DH or no healing. DH did not appear to improve various clinical outcomes in these HIV-infected patients who were taking antiretroviral combinations.28

Mindfulness meditation is the practice of “focusing attention and objectively acknowledging thoughts, emotions, and perceptions as they arise”.29 It appears to be effective in lowering stress. In a study of 46 HIV-infected patients of whom only 24 completed a structured, 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR), the MBSR group had a significant increase in the activity and number of natural killer cells. However, there was no difference in selected psychological, endocrine, or health parameters.29 Researchers in psychoneuroimmunology are continuing to try to demonstrate benefit from meditation. An ongoing NCCAM funded trial is evaluating the effect of MBSR versus an education control intervention on delaying the need to commence ART in naive patients with CD4 cell counts greater than 250 cells/mm3.

BIOLOGICALLY-BASED THERAPIES

In the NCCAM classification, biologically-based therapies include herbs, special diets, and food products used therapeutically (e.g., nutraceuticals). Many of the drugs in common use, as well as a number of potent cytotoxic chemotherapy agents, are derived from the world’s flora. In a comprehensive review, 63 ingredients listed in the Chinese Materia Medica were found to have in vitro activity against HIV.30 These compounds included terpenes, flavinoids, polysaccharides, coumarins, tannins, lectins, quinolones, peptides, and other alkaloids. The natural substances were reported to have activity inhibiting reverse transcriptase, protease and integrase enzymes as well as interfering with infection at the viral cell entry level.

Surveys have shown that herbal usage by patients with HIV ranges from 21% to 68%.2,10,11,31 In the HAART era, the main reason for using herbs is to treat co-morbidities or to alleviate symptoms due to HIV or medications rather than to treat HIV. One concern about the use of herbs is that patients may not be aware of potential herb–antiretroviral drug interactions. In a focus group study of HIV-infected individuals using CAM, all participants knew that St John’s wort decreased the effectiveness of HIV medications. However, the participants did not know of other herbs that could interact with HIV medications. In addition, many of the participants were less concerned about safety issues when it came to CAM therapy compared to Western medicine.32

Herbal Preparations

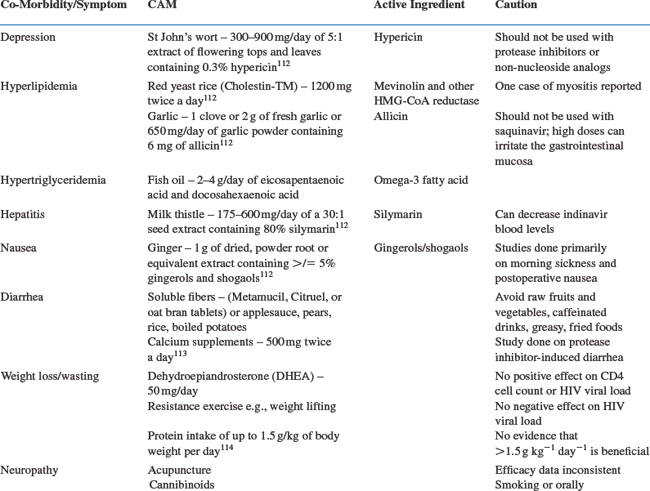

Herbs Used to Treat Co-Morbidities/Symptoms

Depression is common in HIV-infected patients (see Table 32-1). St John’s wort (active ingredient: hypericin) is a popular herb used for depression. The data on the efficacy of St John’s wort for depression is inconsistent but available evidence suggests that specific extracts of St John’s wort may be effective for mild depression.33 St John’s wort is believed to exert its effect by inhibition of the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine by neurons.34,35 More importantly, however, studies have shown that St John’s wort induces cytochrome 450 3A4 isoform and can dramatically lower indinavir levels in healthy volunteers.36 The indinavir area under the curve was reduced by a mean of 57% and the extrapolated 8-h indinavir trough was reduced by 81%. Another study demonstrated that St John’s wort lowered nevirapine levels by 20%.37 This has led to the recommendations in 2005 by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) that St John’s wort not be used with protease PIs or non-nucleoside analogs.38

Hyperlipidemia is a major problem associated with HAART. Garlic (active ingredient: allicin) purportedly has anticholesterol activity and patients may therefore use garlic to reduce their cholesterol levels. The data on the efficacy of garlic to lower lipid levels is limited by the short duration of these studies and the different garlic preparations used in these trials.39 NIH researchers have reported that garlic supplements sharply reduced the blood concentrations of saquinavir by 50%.40 In a classic pharmacokinetic study, nine HIV-negative volunteers received 3 days of saquinavir. They then took garlic capsules twice daily for 3 weeks. At the ensuing analysis, it was found that the saquinavir levels had decreased by 51% and the average maximum concentrations had fallen 54%. Even after a 10 day washout without any further garlic supplementation, the blood levels of saquinavir still averaged 35% lower than baseline values. The 2005 DHHS adult antiretroviral guidelines recommend that garlic not be used with saquinavir.38 There has also been a report of two HIV-positive patients developing significant gastrointestinal side effects from ritonavir after taking garlic.41

Another product that HIV-infected patients may use for hyperlipidemia is cholestin. Cholestin, produced by red yeast fermented on rice has been shown to contain nine monacolins (statins) which inhibit HMG-CoA. Two placebo-controlled trials involving 390 HIV-negative individuals showed a decrease in LDL cholesterol and triglycerides by 20-30%.42 One case of cholestin-induced myopathy has been reported.43 The oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) is another natural source of monacolin and there is an ongoing NCCAM funded study assessing the lipid lowering effect of oyster mushrooms in HIV-positive patients with ART related hypercholesterolemia.44

Milk thistle (active ingredient: silymarin) is used for its hepatoprotective or hepatorestorative properties. This property is especially attractive to HIV patients co-infected with hepatitis B and/or C who may be at an increased risk to develop transaminase elevations in response to HAART. However, the current available data on the positive effect of milk thistle on the liver is inconclusive.45 As with other herbs, milk thistle can have an effect on PI blood levels. In ten healthy individuals, milk thistle decreased mean indinavir levels by 25%.46 Milk thistle in the dosages generally used probably should not interfere with the efficacy of PIs.

Herbs Used for Its Anti-HIV Activity

Some plant products have been investigated for their antiretroviral activity. St John’s wort (hypericin) has reputed broad-spectrum antiviral effects against HIV, herpes, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein–Barr virus.47 In vitro, hypericin inhibits HIV replication. However, hypericin blood levels after oral dosing were less than one-hundredth of the test-tube levels that showed anti-HIV effect. A study of high intravenous doses of hypericin was terminated because participants developed hepatotoxicity and photodermatitis.48

Calanolide A derived from the Malaysian rain forest tree, Calophyllum lanigerum has significant in vitro activity against HIV. Calanolide A functions like a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 43 HIV-infected patients who received 14 days of Calanolide A 600 mg twice a day had a mean HIV viral load reduction of 0.81log10 from baseline when compared to the placebo group.49

In a recent Cochrane review that looked at nine randomized, placebo-controlled trials evaluating eight herbal products to treat HIV involving 499 HIV-positive individuals, the authors concluded that the evidence did not support the use of these products to suppress HIV infection. The authors do point out that potential benefits need to be confirmed in larger rigorous clinical trials.50

Herbs Used for Stimulating the Immune System

There are several herbal products used by HIV-positive individuals that are thought to stimulate the immune system such as Echinacea, mistletoe, goldenseal, shiitake and reishi mushrooms, aloe, and garlic. While each has a theoretical basis, with evidence of active ingredients and groups of vocal users and supporters, each still needs to be researched further in people with HIV infection.51 The interactions between HIV and the immune system are so intricate that the idea of “stimulating the immune system” is an obvious oversimplification. A stimulus to CD4 cells might help the body fight infections or instead might lead to increased viral replication. Boosting certain cytokines like interleukin-2 or interleukin-12 may help the host, while boosting other cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor alpha may lead to disease progression. For example, echinacea, a member of the daisy family, is widely used in short-term pulses as prophylaxis and treatment for upper respiratory infections despite negative results from recent trials in HIV-uninfected populations.34,35,52 Whereas, immunostimulatory effects have been demonstrated with short-term use, there is concern that long-term use of greater than 8 weeks duration may be associated with the potential for immunosuppression.53 This theoretical concern has led some to recommend that chronic use of echinacea is contraindicated in patients with HIV infection, although no data from controlled trials is available.35 The German E monograph also recommends that echinacea not be used in HIV-infected individuals.54

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree