739

Comorbidity in Cancer

Grant R. Williams and Holly M. Holmes

INTRODUCTION

Older adults with cancer respond differently to treatments than do younger patients. Older patients more often present with multiple medical conditions, in addition to their cancer diagnosis, that can complicate their oncologic treatment and tolerance. The majority of Medicare beneficiaries have two or more medical conditions and nearly 25% have four or more conditions (1). Over the last decade, the importance of comorbid medical conditions in cancer care has become more elucidated, yet due to stringent eligibility criteria and the lack of systematic measurement in clinical trials there is a limited evidence base for making informed decisions (2). Most clinical practice guidelines, including in oncology, are single-disease focused, with limited interpretability in patients with multiple comorbidities (3).

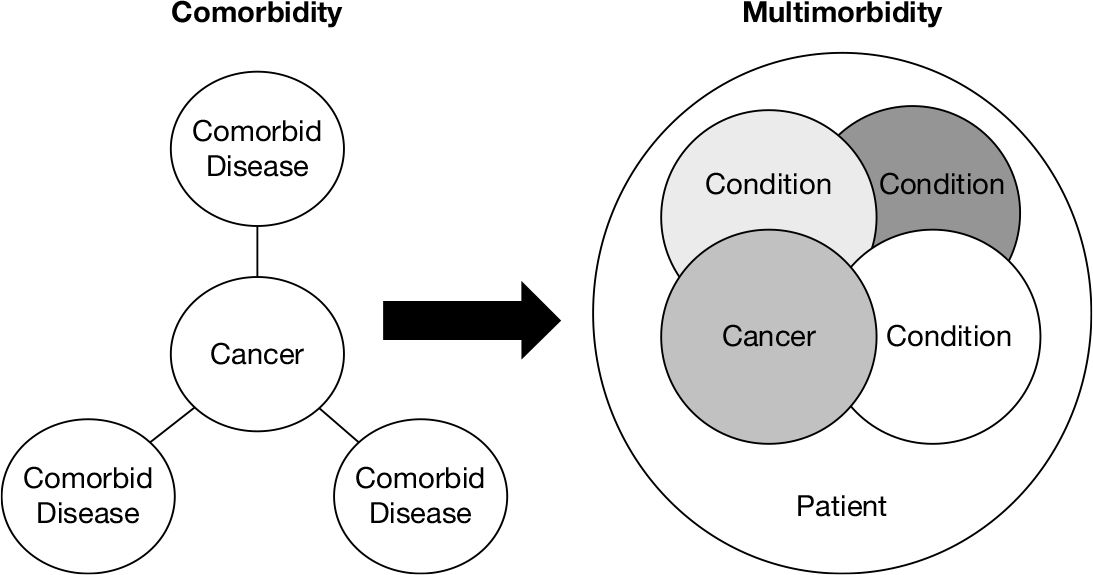

Historically, cancer has been considered an index condition and other diseases have been approached as comorbidities, defined as medical conditions that exist along with an index condition. A newer concept of “multimorbidity” has been used to reflect a model which shows that many diseases and treatments for disease impact other conditions and interact with each other to positively or negatively affect an individual’s health, leading to overlapping medical conditions within the same patient (see Figure 9.1) (4,5). 74The approach to an individual with multimorbidity requires a new paradigm to provide individualized care that takes into account guiding principles that will be discussed later in this chapter. Multimorbidity is defined as the coexistence of two or more chronic conditions in which one is not necessarily more central than the others (6). As this chapter specifically focuses on comorbid illnesses within the context of cancer, we will frequently use the term comorbidity regardless of the number and severity of comorbid conditions.

FIGURE 9.1 Conceptual differences between comorbidity and multimorbidity.

Source: Adapted from Ref. (4). Boyd C, Fortin, M. Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev. 2010;32(2):451–474.

RELEVANCE IN CANCER

Comorbid illnesses can impact cancer in a variety of ways, as the comorbid conditions themselves comprise a wide-range of heterogeneous conditions of varying severity and number. The majority of observational studies have found that cancer patients with increased comorbidities have poorer survival compared to those without comorbidity, with 5-year mortality hazard ratios ranging from 1.1 to 5.8 (7). The impact of comorbid conditions on survival in cancer partly depends on the aggressiveness and lethality of the cancer itself. The presence of moderate to severe comorbidities is of greatest prognostic importance in early stage and potentially curable patients, while in more aggressive cancers, where the mortality is dominated by the primary malignancy, there is often less impact (8).

Comorbidities can also impact the tolerability of cancer treatments. Patients with more comorbid conditions are at an increased risk of severe toxicity and hospitalization during chemotherapy treatment (9–11). In a study examining older adults undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer, patients with a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of ≥1 were three times more likely to experience grade 3 or higher chemotherapy toxicities (11). Severe comorbid conditions (CCI ≥ 3) have been shown to be one of the strongest predictors of hospitalizations related to chemotherapy, with 10-fold higher hospitalization rates compared to patients with no comorbidities (10). Furthermore, comorbid patients are less likely to complete chemotherapy (12). As comorbid conditions can alter both the risk and benefit of cancer treatments, they can dramatically impact the risk/benefit balance of many treatments (2). The presence of comorbidities is one of the most frequent reasons cited in the medical chart for nonreceipt of cancer treatment (13,14).

ASSESSING COMORBIDITIES

There are many methods for assessing comorbidity in cancer, ranging from simple counts of conditions to weighted indices to system-based methods. Although comorbidity indices are frequently used in research settings, in the clinical setting a comprehensive history and physical with a list of comorbidities and their current treatments is frequently the only method used to assess comorbid illness. While this approach has some advantages and is already incorporated into our current clinical practice processes, there are additional advantages to using validated tools when assessing patients in the clinic. For one, describing comorbidity in terms of an index or tool makes communication about prognosis and impact on chemotherapy toxicity 75more standardized with patients and between colleagues caring for a patient. Validated tools also provide a more systematic description of the severity or burden of comorbidity than is used in a simple history and physical. For example, a heart attack might get more weight than a known history of coronary artery disease. Finally, using a comorbidity tool might help to frame a patient’s likely outcome when extrapolating evidence from clinical trials, in which participants are only described in terms of an index.

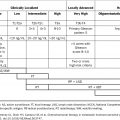

There is no single gold standard to assess comorbidity, and a 2012 review identified 21 distinct approaches to assess comorbidity that have been used in cancer populations (15). The choice of comorbidity tool depends on the clinical setting and intended use of the instrument (2). For example, in a clinical setting primarily consisting of older patients with multimorbidity, a tool that allows capture of number and severity of comorbidities as well as the effect on daily function or quality of life might be most clinically useful. Some tools are simply not designed for clinic and are better suited for use with retrospective reviews of medical records or with claims data. See Table 9.1 for a list of selected comorbidity tools that are commonly used in oncology. There are many online calculator versions of several comorbidity tools, which may make them more usable in a clinic setting. Several detailed reviews of comorbidity methods are available for a more in-depth examination (15,26).

TABLE 9.1 Common Comorbidity Measurement Tools

Type | Index | Items and Rating |

Summative | ||

Elixhauser (16) | 30 dichotomous conditions | |

Weighted | ||

CCI (17) | 19 conditions weighted 16 | |

16 conditions weighted by empirically derived weights | ||

Systems-based | ||

CIRS (20) | 13 or 14 organ system categories, each rated 0–4 | |

ICED (21) | Disease severity subindex: 14 diseases (rated 0–4). Functional severity subindex: 12 conditions (rated 0–2). Total: 0–3 | |

KFI (22) | 12 conditions, each rated 0–3 | |

ACE-27 (23) | 27 conditions, each rated 0–3 | |

Cancer specific | ||

WUHNCI (24) | 7 conditions, each rated 0–4 | |

HCT-CI (25) | 17 conditions, each rated 0–3 |

ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CIRS, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; ICED, Index of Coexistent Disease; KFI, Kaplan–Feinstein Index; WUHNCI, Washington University Head and Neck Comorbidity Index.

76One of the most widely used and simplest comorbidity scales is the CCI. The index includes 19 conditions with individual weights (ranging from 1 to 6) based on the relative risk of death. In the CCI, myocardial infarction is weighted with 1 point, and metastatic cancer is weighted with 6 points. Patient-reported versions of the CCI have been validated that can be easily administered in the clinic, and an age-adjusted version has also been created (age-adjusted CCI) (27–29). Four of the items within the CCI are related to cancer and should be excluded if they apply to the cancer population in which they are used. For example, if the CCI is to be used in a clinic of solid tumor patients, the solid tumor would not be included; however, patients with lymphoma in addition to a solid tumor would still have points added for lymphoma. Although the range of scores is often small, with a highly skewed distribution toward lower scores (26), the CCI is a quick tool for systematic comorbidity measurement.

For a more detailed evaluation of comorbidity, many utilize the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS). The CIRS categorizes comorbidities by organ system affected and rates them according to their severity from 0 to 4, similar to the Common Toxicity Criteria grading (none, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe/life-threatening) (20). More severe ratings also equate to greater functional burden as a result of the condition. Although the CIRS requires more training than the CCI in order to assess the severity of diseases, it can be performed in a few minutes by clinicians with a working familiarity of the manual (26).

The Older Americans Resources and Services Questionnaire (OARS) Physical Health subscale is frequently used as part of the patient-reported portion of the brief geriatric assessment developed by Hurria et al. (30,31). The OARS comorbidity scale is patient-reported and assesses 14 specific comorbid conditions and the degree to which each interferes with the participant’s activities. The OARS questionnaire is unfortunately not easily available to clinicians for daily use, but is increasingly being incorporated in research studies and can be easily performed by patients without assistance. Finally, disease-specific comorbidity tools have been developed for use in certain cancers and can be particularly helpful when available (24,25,32). As choosing the right comorbidity measure depends on the clinical context, there is no single preferred method, but some form of systematic incorporation of comorbid conditions, such as the CCI, CIRS, or OARS, is highly recommended in older adults with cancer.

TREATING THE PATIENT WITH CANCER AND MULTIPLE COMORBIDITIES

A thorough assessment of comorbidities is necessary given their likely impact on cancer and cancer therapy. Once information on comorbid conditions has been obtained, there are several ways in which such information could be used clinically:

1. To adjust cancer regimens in light of comorbid illness. For example, dose adjustment of renally dosed chemotherapy in the setting of chronic kidney disease, or adjustments in anesthesia or surgical plan for patients with substantial cardiac or lung disease.

2. To anticipate higher risks for toxicity. For example, patients with comorbid peripheral neuropathy due to diabetes may have more difficulties with neurotoxic chemotherapy regimens.

773. To better optimize existing comorbid conditions during cancer therapy. Many patients who present with cancer may not have received regular primary care, and may need to have comorbid conditions more fully addressed and treated.

4. To better estimate prognosis independent of cancer. Patients with multiple severe comorbid illness have a lower likely remaining life expectancy than their age-matched peers with few illnesses. This information is a necessary first step to putting cancer-specific prognosis in perspective, particularly in the adjuvant treatment setting (33).

GUIDING CARE PRINCIPLES

In the absence of a substantial evidence base to guide clinical management and decision making in patients with multiple comorbidities, clinicians need practical guidance for a rational approach to manage these complicated patients (34). The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) convened an expert panel on the care of older adults with multimorbidity with the goal of developing an approach by which clinicians could provide optimal care for this challenging population (35). Based on a review of the literature and expert opinion, the panel developed a set of Guiding Principles for the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity. They include: (a) assessing patient preferences, (b) interpreting and applying available information, (c) estimating prognosis, (d) considering treatment feasibility, and (e) optimizing therapies and care plan. These are meant to provide a framework to help structure decision making and not as a formalized treatment “guideline.” See Table 9.2 for an outline of how these principles can be applied to multimorbid patients with cancer (adapted and modified from Thompson et al. (34)). For a detailed review of adapting the principles into oncologic management, a recent “Geriatrics for Oncologists” article is available in the Journal of Geriatric Oncology (34) on how to best manage the care of older patients with cancer and multimorbidity.

TABLE 9.2 Guiding Principles for the Care of Older Adults With Cancer and Multimorbidity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree