26527

Communication With Cognitively Impaired Older Adults and Their Families

Rebecca Saracino, Christian J. Nelson, and Andrew J. Roth

Cancer steadily increases in prevalence as people age (1). Simultaneously, communication difficulties become compounded when older adult patients must deal with multiple deficits including sensory losses and physical frailty (2). These issues can become extremely challenging when older patients have cognitive deficits and begin losing or have lost aspects of their autonomy and independence. These challenges arise across the cancer experience (Table 27.1), and affect not only the patient, but also informal caregivers, clinicians, and treatment team members (2). The challenge for oncology staff is to know how to communicate appropriately with patients across circumstances. Benefits of improved communication also include enhancement of trust, improvement in the accuracy of information and understanding, and a decrease in the frequency of mistakes (4). Unfortunately, little research has been done in the area of communicating with elderly cancer patients who have cognitive deficits. Thus, this chapter reviews the existing communication literature from the field of geriatric psychiatry and cognitive disorders, and attempts to provide practical solutions for common problems that arise in the oncology setting.

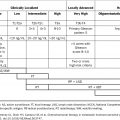

TABLE 27.1 Critical Time Points to Consider Patients’ Capacity

■ Soon after diagnosis and when there is a need to make treatment decisions, including the complex choice of whether to treat or not treat the cancer, depending on the overall health and multiple medical comorbidities of the patient and likely life expectancy |

■ Informed consent issues for medical procedures |

■ Dealing with health care proxies, especially when there is no other family or supportive family member around |

■ Dealing with issues of independent living |

■ When dementia is present at diagnosis or arises in the midst of chronic treatment for cancer |

■ In dealing with confusion or delirium in the general ward setting |

Source: From Ref. (3). Roth A, Nelson, C. Issues for cognitively impaired elderly patients. In Kissane D, Bultz B, Butow P, Finlay I, eds. Handbook of Communication in Oncology and Palliative Care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:547-556.

266COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Dialogues between physicians and elderly patients are often marked by ineffective communication, as a result of characteristics of the physician and/or patient and circumstances that can make these encounters particularly challenging. Patients of all ages report significant levels of unmet needs, particularly in the following realms of communication: information provision, psychosocial support, and response to emotional cues (5). These issues are particularly relevant to older patients, and attending to these unmet needs is crucial for optimal care. For example, research has demonstrated that the communication process in initial consultations may influence a patient’s psychological health and adherence over time. Patient satisfaction is consistently related to provider behavior (6). Clinicians, therefore, may benefit from improving communication with older patients during medical visits. The most effective method for learning communication skills is observation of ideal and effective communication strategies, followed by rehearsing the skills in role-play, receiving immediate feedback on performance to permit modification, and then repeating the practice (7). In this way, the trainee has the opportunity to hone his or her own communication patterns without negative experiences. This positive experiential process has been recognized as the central component in successful acquisition of communication skills.

Working with multiple clinical staff and maintaining appropriate communication among these staff members may be specifically important in working with cognitively impaired elderly patients. For example, in an inpatient service, there is a need for accurate information to be handed on from one shift to another and from one specialty to another, as staff cannot rely on the cognitively impaired patients to give accurate information. The problems of evaluating changes and monitoring responses to various treatments are heightened if each of the health care professionals does not have the same understanding of the patient’s needs. Some professionals may not realize that patient input may be misleading. Direct verbal communication as well as accurate and clear charting are imperative.

WORKING WITH FAMILY MEMBERS

The views of family members, their interpretations of medical issues, and how much they are allowed to participate in helping patients make decisions are also important concerns. Often, cognitive changes are not static, though they may be stable for some time depending on the cause and trajectory of the illness and other factors; it is important for a clinician to distinguish reversible from irreversible changes in cognition, as these can significantly affect treatment decisions and prognoses. Relatives or caregivers bring their subjective biases to the situation, which may or may not be relevant to the patient’s primary needs. Therefore, decisions about who is an appropriate supplementary historian while protecting patient confidentiality is an important consideration. The relatives or caregivers may only see the patient at selected times or may be overwhelmed and frustrated with caregiver burden. As a result, it is important to be able to elicit accurate information from the patient’s perspective as well as that 267of the relative or caregiver. Consider seeing patients alone first, in order to understand their perception of the situation and if there is anything they want to disclose to you without the caregiver or relative in the room. There are times that this need is not perceived until you have met with the family member and reviewed the situation. It may also be important to maintain structure and limits during the consult, attempting to remain neutral while listening to and considering all perspectives and concerns. There are also times when a family member may be domineering and push a specific course of treatment or management; in such instances, it is important to continue to use your clinical judgment and perhaps request consultations from other services such as a patient representatives or social worker to help understand and better manage the situation. There can also be gains by teaching caregivers of those with cognitive deficits how to communicate better with their loved ones (8) (Table 27.2).

TABLE 27.2 Skills to Help Communicate With Cognitively Impaired Older Adults

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree