In gynecologic oncology, as in all branches of medicine, the clinical encounter with the patient—and often the family—has four specific aims. The first is to gather information from the patient in order to determine the clinical diagnosis; the second is to transmit information to the patient in order to communicate the treatment plan; the third is to build a relationship in order to establish rapport and trust; and the fourth is to support the patient and her family through the crisis of her illness. When accomplished successfully, these aims can achieve the overarching goals of producing objective improvement in the patient’s medical condition to the extent medically possible—helping the patient get better—and subjective changes in how she experiences her care—helping the patient to feel better.

The last two aims take on particular significance because the increased survival rates of many cancers can extend the relationship with the oncologist and the clinical team over many years, and encompass a progression of disease crises. The median survival for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer has increased over the past 20 years, and it is not uncommon for patients to experience remission and recurrence four or five times during the course of their illness (1). Each disease recurrence can be a crisis in which the patient receives bad news again, and must endure the rigors of a new round of treatment, uncertainty about the outcome, and the threat of death. In these instances, the application of supportive communication skills in the context of a long-standing relationship with the patient can reduce anxiety, facilitate patient coping, and assist in providing the patient with hope (2–5).

Regardless of whether medical improvement is possible, accomplishment of these goals can produce amelioration of the patient’s subjective symptoms. Communication skills are essential for both. This chapter sets out a basic and practical approach for acquiring and improving effective communication skills.

Why Communication Skills Matter

Good communication skills facilitate the clinician’s ability to take an accurate clinical history, make a correct diagnosis, and formulate an appropriate plan of management. Communication skills are a central component of every clinician’s management techniques. Communication expertise can change the patient’s attitude to the entire medical intervention.

Effective communication can change the way a patient feels about the clinical outcome. Communication skills may affect what the patient perceives has happened to her, her assessment and feelings about her management, her treatment, and her healthcare team (6). Communication and interpersonal skills matter greatly to patients and are an important determinant of satisfaction with care (7). The literature suggests that patients are both likely to choose and to change physicians based on how they perceive their physician communicates and interacts with them (8).

An important and related issue is that of medical–legal implications. Communication skills have been shown to be a determinant of more objective outcome measures, such as litigation. Approximately three-fourths of complaints against medical practitioners are caused not by matters of medical management, but by failures or obstacles in communication. Levinson and Chaumeton (9) have shown that communication skills are a major factor in distinguishing those clinicians who are sued from those who are not.

Patients are very sensitive to communication messages from their oncologists. Using samples of dialogue from interactions between surgeons and their patients, Ambady et al. (10) were reliably able to predict those surgeons most likely to be sued. Those whose voice communicated lack of empathy and concern toward the patient were more than twice as likely to have had a malpractice claim filed against them. Many insurance companies in North America reduce their malpractice premiums for physicians who have attended specific programs in communication skills.

Communication skills are particularly essential for ensuring informed consent, enlisting the family in the care of the patient, reducing the uncertainty associated with a new or recurrent illness, and increasing accrual to clinical trials (11–13).

Communication Skills as Learnable Techniques

Why Communication Skills Are So Challenging to Learn

Most oncologists have had little preparation in communicating with patients (11,14,15). Very few have had any formal course work and a fair number learn by observing other clinicians, which is not a guarantee of success. Many clinical encounters are highly emotionally charged, such as breaking bad news and making the transition to palliative care. The clinician is challenged not only to address the patient’s feelings, but also his or her own, which can be characterized by the sense of helplessness and frustration in the face of incurable disease, or self-doubt about having done everything possible for the patient (12,16). These feelings may cause the doctor to offer false hope to the patient, avoid discussing issues important to the patient such as disease prognosis and end-of-life issues (17,18), or offer treatment when there is little or no chance of success (19).

Acquiring Communication Skills

Since the late 1970s, clinicians have become increasingly aware of the need for improved communication skills, but defining and testing techniques that can be acquired by practitioners was initially difficult. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was widely believed that communication skills were intuitive, almost inherited talents—“You’ve either got the gift or you haven’t.” This was coupled with the belief that somehow the physician would be able to feel or sense what the patient was thinking, to divine what the patient wanted, and be able to respond intuitively in an appropriate way. This belief alienated a large proportion of healthcare professionals, who found the whole topic, as taught at that time, excessively “touchy-feely,” intangible, and amorphous, with no guidelines that could lead even a highly motivated practitioner to improve his or her skills.

Since the mid-1980s, researchers and educators have shown that communication skills can be taught and learned and retained over years of practice, and that they are acquired skills, like any other clinical technique, and not inherited or granted as gifts (20–24).

The main part of this chapter describes two practical protocols that can be used by any healthcare professional to improve her or his communication skills. They are (i) a basic protocol, the CLASS protocol, which may serve for all medical interviews and (ii) a variation of that approach, the SPIKES protocol, for breaking bad news.

Illustrations of Practical Techniques

The CLASS and SPIKES protocols are summarized briefly using simple and practical guidelines or rules. Both protocols have been published in greater detail elsewhere as a textbook (25), a booklet (26), and in illustrated form using videotaped scenarios of interactions between standardized patients (27). Review of this video material can enhance the understanding of these communication techniques.

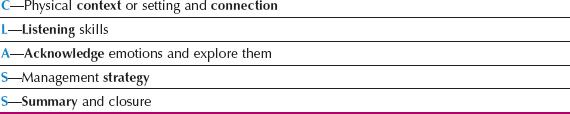

Table 24.1 The CLASS Protocol

CLASS: A Protocol for Effective Communication

There are probably an infinite number of ways of summarizing and simplifying medical interviews, but few if any are practical and easy to remember. The five-step basic protocol for medical communication set out in the following sections, which has the acronym CLASS, has the virtue of being easy to remember and to use in practice. Furthermore, it offers a relatively straightforward, technique-directed method for dealing with emotions. This is important, because one study showed that most oncologists—more than 85%—believe that dealing with emotions is the most difficult part of any clinical interview (28).

Trust and rapport are especially important to patients at times of medical crisis. Communication skills such as exemplified in the CLASS protocol underpin the establishment of confidence and a working relationship with the patient and her family.

In brief, the CLASS protocol identifies five essential components of the medical interview. They are Context—the physical context or setting, and Connection—or building rapport, Listening skills, Acknowledgment of the patient’s emotions, Strategy for clinical management, and Summary (Table 24.1).

C—Context—or Setting & Connection—or Building Rapport

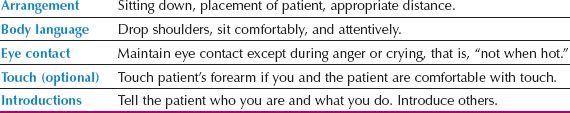

The context of the interview means the physical context or setting and connection means the steps that are necessary to begin building rapport or a relationship with the patient. Both these steps are important because they encourage trust on the part of the patient and family, an essential ingredient of any collaborative endeavor. They are especially important in the first encounter, during which the most lasting impressions are often formed. The essential components are listed in Table 24.2. The first component is to arrange the space optimally. The second is to get your own body language right. It is important to pay attention to eye contact, to whether touch is helpful, and to making introductions.

A few seconds spent establishing these features of the initial setup of the interview may save many minutes of frustration and misunderstanding later for the professional and the patient. These rules are not complex, but they are easy to forget in the heat of the moment.

Spatial Arrangements

The Setting

Every attempt should be made to ensure privacy. In a hospital setting, if a side room is not available, the curtains should be drawn around the bed. In an office setting, the door should be shut. Any physical objects such as bedside tables, trays, or other impediments should be moved out of the line between the physician and the patient, and the television or radio should be turned off. In an office setting, the physician’s chair should be moved adjacent to that of the patient. This can create a sense of the physician being more within reach and more connected to the patient (29).

Table 24.2 The Elements of Physical Context

Clutter and papers should be moved away from the area of desk nearest to the patient, and the physician should not talk while reading the chart. If any of these actions seem awkward, an option would be to state “It may be easier for us to talk if I move the table/if you turn the television off for a moment.”

The most important rule of all is that the physician should sit down. This is an almost inviolable guideline. It is virtually impossible to assure a patient that she has a doctor’s undivided attention if he or she remains standing. Anecdotal impressions suggest that when the doctor sits down, the patient perceives the period of time spent at the bedside as longer than if the doctor remains standing. The act of sitting indicates to the patient that she has control at a time when most patients are feeling that it is not they who are “calling the shots.” It also indicates that the doctor is there to listen, saves time, and increases efficiency.

Before starting the interview itself, care should be taken to get the patient organized if necessary. After a physical examination, the patient should be allowed time to dress, to restore the sense of personal modesty.

Distance

It is important to be seated at a comfortable distance from the patient. This distance—sometimes called the “body buffer zone”—seems to vary from culture to culture, but a distance of 2 to 3 ft usually serves the purpose for intimate and personal conversation (29). This is another reason why the doctor who remains standing at the end of the bed—“6 ft away and 3 ft up,” known colloquially as “the British position”—seems remote and aloof.

The height at which the doctor sits can also be important; normally, his or her eyes should be approximately level with those of the patient. If the patient is already upset or angry, a useful technique is to sit so that the doctor’s eyes are below those of the patient. This often decreases the anger. The doctor should try to look relaxed, even if he or she is not feeling that way.

Positioning

The doctor should ensure that he or she is seated closest to the patient whenever possible, and that any friends or relatives are on the other side of the patient. A clear signal should be sent to relatives that the patient has primacy.

Have Tissues Nearby

In almost all oncology settings, it is important to have a box of tissues nearby. If the patient or relative begins to cry, they should be offered tissues. This not only gives overt permission to cry, but also allows the person to feel less vulnerable when crying.

Body Language

It is important to look relaxed and unhurried by sitting down comfortably with both feet flat on the floor, shoulders relaxed and dropped, coat or jacket undone, and hands rested on the knees—often called “the neutral position” in psychotherapy. Attention should be paid to nonverbal behavior, because it may communicate that the doctor is listening and concerned. For example, listening with the arms folded may imply to the patient that the doctor’s mind is already made up, and that no further discussion is encouraged.

Eye Contact

Eye contact should be maintained for most of the time while the patient is talking. If the interview becomes intense or emotionally charged—particularly if the patient is crying or is very angry—it is helpful to the patient at that point for the doctor to look away—to break eye contact.

Touching the Patient

Touch may also be helpful during the interview if (i) a nonthreatening area is touched, such as the hand or forearm; (ii) the doctor is comfortable with touch; and (iii) the patient appreciates touch and does not withdraw.

Most clinicians have not been taught specific details of clinical touch at any time in their training (30). They are, therefore, likely to be ill at ease with touching as an interview technique until they have had some practice. Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence, although the data are somewhat soft, that touching the patient, particularly above the patient’s waist to avoid misinterpretation, is of benefit during a medical interview (31). It seems likely that touching is a significant action at times of distress and should be encouraged, with the proviso that the professional should be sensitive to the patient’s reaction. If the patient is comforted by the contact, it should be continued; if the patient is uncomfortable, it should be stopped. Touch can be misinterpreted, for example, as lasciviousness, aggression, or dominance, so the doctor should be aware that touching is an interviewing skill that requires extra self-regulation.

Starting Off

Introductions

The doctor should ensure that the patient knows who he or she is. Many practitioners make a point of getting up and shaking the patient’s hand at the outset, although this is a matter of personal preference. Often the handshake may tell something about the family dynamics as well as about the patient. Frequently the patient’s spouse will also extend his hand. It is worthwhile making sure that the patient’s hand is shaken before that of the spouse, even if the spouse is nearer, to demonstrate that the patient is the most important person in this context. The “white-coat syndrome” is a well-known phenomenon that describes how the medical setting induces anxiety in many patients—often even leading to blood pressure increases—so a friendly greeting may go a long way at putting the patient at ease.

Others in the medical team should also be introduced by the doctor, for example, medical students, nurses, and the patient should introduce her supporters. At times, when there are many relatives present, as is not uncommon when there is a new diagnosis of cancer, it is judicious to ask the patient “which two people would you like to come with you now?” In this way except for family meetings, the physician will not be overwhelmed by the number of people that need to be addressed.

L—Listening Skills

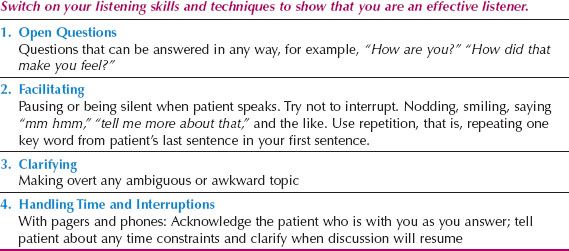

As dialogue begins, the professional should show that she or he is in “listening mode.” For a general review of interviewing skills, see Lipkin et al. (32). The four main points to attend are covered in the following sections. They are the use of open questions, facilitation techniques, the use of clarification, and the handling of time and interruptions (Table 24.3).

Open-Ended Questions

Open questions are simply questions that can be answered in any way or manner of response. In other words, the questions do not direct the respondent or require her to make a choice from a specific range of answers. In taking the medical history, of course, most of the questions are, appropriately, closed questions—“Do you have swelling of the ankles?” “Have you had any bleeding after your menopause?” In therapeutic dialogue, when the clinician is trying to be part of the patient’s support system, open questions are an essential way of finding out what the patient is experiencing as a way of tailoring support for her. Hence, open questions—“What did you think the diagnosis was?” “How did you feel when you were told that . . . ?” “How did that make you feel?” are a mandatory part of the “nonhistory” therapeutic dialogue. A very useful phrase to use when it is unclear what a patient is trying to say is “tell me more,” which invites the patient to expand on her thoughts or feelings.

Table 24.3 Fundamental Listening Skills

Facilitation Techniques

Silence

The first and most important technique in facilitating dialogue between the patient and clinician is silence (33). If the patient is speaking, she should not be talked over. This, the simplest rule of all, is the one most often ignored, and it is most likely to give the patient the impression that the doctor is not listening.

Silences also have other significance: They can be—and often are—revealing about the patient’s state of mind. Often, a patient falls silent when she has feelings that are too intense to express in words. A silence, therefore, means that the patient is thinking or feeling something important, not that she has stopped thinking. If the clinician can tolerate a pause or silence, the patient may well express the thought in words a moment later.

If breaking the silence is necessary, the ideal way to do so is to say “What were you thinking about just then?” or “What is it that’s making you pause?” For the physician, silence is especially important after giving bad news. The patient’s silence should not be addressed with reassurance or other “fix it” statements, which may make the doctor feel better, but which cut off the ability of the patient to process emotion.

Other Simple Facilitation Techniques

Having encouraged the patient to speak, the doctor should prove that he or she is hearing what is being said. This may be demonstrated by the following techniques: Nodding, pausing, smiling, saying “Yes,” “Mmm hmm,” “Tell me more,” or anything similar.

Repetition and Reiteration

Repetition, after sitting down, is probably the second most important technique of all interviewing skills. To show that the doctor is really hearing what the patient is saying, one or two key words from the patient’s last sentence should be used in his or her own next sentence: “I just feel so lousy most of the time”; “Tell me what you mean by feeling lousy.” Reiteration means repeating what the patient has said in the doctor’s own words: “Since I started those new pills, I’ve been feeling sleepy”; “So you’re getting some drowsiness from the new pills.” Both repetition and reiteration confirm to the patient that she has been heard.

Reflection

Reflection is the act of restating the patient’s statement in terms of what it means to the clinician. It takes the act of listening one step further and shows that the patient has been heard and interpreted correctly: “If I understand you correctly, you’re telling me that you lose control of your waking and sleeping when you’re on these pills.”

Clarification

Patients often have concerns about treatment or other issues related to their care. When not asked about them directly, they may hint or express them in nuances, protests, or questions that are not clear. Listed below are some examples of how important information may be indirectly communicated.

Statement: “I don’t know how my family can take any more of this.”

Patient means: “I really feel guilty.”

Statement: “I just couldn’t stand another round of chemo.”

Patient means: “I felt so awful when my hair fell out.”

Statement: “Doctor, how long do you think I have to live?”

Patient means: “I wonder if I’ll see my grandson graduate.”

Statement: “What will the end be like?”

Patient means: “How much will I suffer?”

As the patient talks, it is very tempting for the clinician to go along with what the patient is saying, even when the exact meaning or implication is unclear. This may lead very quickly to serious obstacles in the dialogue.

It is important to be honest when the patient’s meaning is not understood. Many different phrases can be used—“I’m sorry—I’m not quite sure what you meant when you said . . . ,” “When you say . . . do you mean that . . . ?” Clarification gives the patient an opportunity to expand on the previous statement or to amplify some aspect of the statement, now that the clinician has shown interest in the topic. The key to addressing questions is to use clarifying statements that get at the issue underlying the expressed concern.

Handling Time and Interruptions

Clinicians have a notorious reputation for being impolite when handling interruptions—by phone, pager, or other people, often appearing to abruptly ignore the patient, and going immediately to the phone, or responding immediately to the pager or to a colleague. This appears as a snub or an insult to the patient.

If calls cannot be ignored or pagers turned off—and most cannot—it is important to express sorrow to the patient about the interruption: “Sorry, this is another doctor that I must speak to very briefly—I’ll be back in a moment.” “This is something quite urgent about another patient—I won’t be more than a few minutes.” The same is true of time constraints: “I’m afraid I have to go to the O. R. now, but this is an important conversation. We need to continue this tomorrow morning on the ward round …”). If it is known that an important phone call is expected, the patient should be informed ahead of time so that she feels respected.

A—Acknowledgment—and Exploration—of Emotions

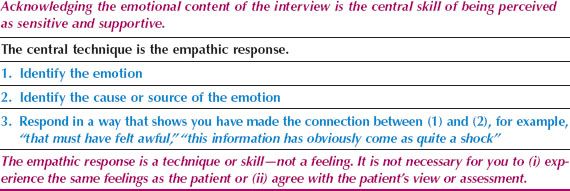

The Empathic Response

The empathic response is an extremely useful technique in an emotionally charged interview, yet is frequently misunderstood by students and trainees (Table 24.4).

The empathic response has nothing to do with the doctor’s personal feelings. Sadness in the patient does not require the doctor to feel sad at that moment. It is simply a technique to acknowledge to the patient that the emotion she is experiencing has been observed. Importantly, empathic responses are correlated with the degree of support that the patient experiences (34).

The empathic response consists of three mental steps:

1. Identifying the emotion that the patient is experiencing.

2. Identifying the origin and root cause of that emotion.

3. Responding in a way that tells the patient that the connection between steps 1 and 2 has been made.

Often, the most effective empathic responses follow the format of “You seem to be . . .” or “It must be,” for example, “It must be very distressing for you to know that all that therapy didn’t give you a long remission” or even “This must be awful for you.” The objective of the empathic response is to demonstrate to the patient that the emotion she is experiencing has been identified and acknowledged, thereby giving it legitimacy. It is a way of saying to the patient “it’s ok to feel that way.”

Table 24.4 Acknowledgment of Emotions: The Empathic Response

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree