8 Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Surveillance

Introduction

The earliest known tool for luminal evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract was the Lichtleiter, or light conductor. Invented by Philipp Bozzini in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1806, this instrument used a candle as the source of illumination for rectoscopy1 (Fig. 8-1). Almost a century later, in 1894, Howard Kelly2 of Johns Hopkins University introduced the first rigid rectosigmoidoscopes, which allowed visualization to a depth of 30 cm. Over the next 5 decades, poor illumination, limited depth, and patient discomfort continued to present challenges to the clinician. Not until the 1950s did a true revolution in endoscopy occur. During this period, Narinder Singh Kapany3 invented flexible optical fibers. Using this newfound technology, Basil Hirschowitz4 of the University of Michigan created the first fiber optic endoscope. As the earliest tool to overcome the seemingly inherent obstacles associated with prior techniques, this modality of luminal gastrointestinal investigation soon came into common practice. The incorporation of new technologies such as the snare device for polypectomy in the late 1960s5 augmented not only the diagnostic but also the therapeutic potential of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy.6

Indications for Screening

The goal of a CRC screening program is to detect precancerous and cancerous lesions early so that interventions will lead to improved outcome while appropriately making use of available resources. CRC or the precursor lesion, adenomatous polyps, may affect diverse patient populations, including asymptomatic persons, those who have had a polypectomy, and those who have had a CRC surgical resection, and special populations such as those with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or with hereditary/genetic predispositions. The creation of a viable screening and surveillance program needs to be diverse enough to incorporate all those at risk for CRC. To that end, risk stratification is of paramount importance to ensure appropriate implementation of screening and surveillance guidelines. However, this task is fraught with challenges, such as resource limitations, the economic burden of covering expenses, and clinician aptitude. Also vital to the success of a CRC screening program are patient compliance and willingness to participate, sensitivity and specificity of screening modalities, accessibility, and overall benefit with minimized risk.

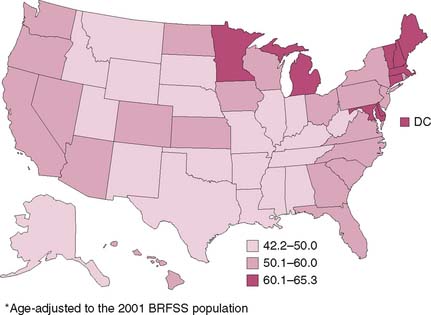

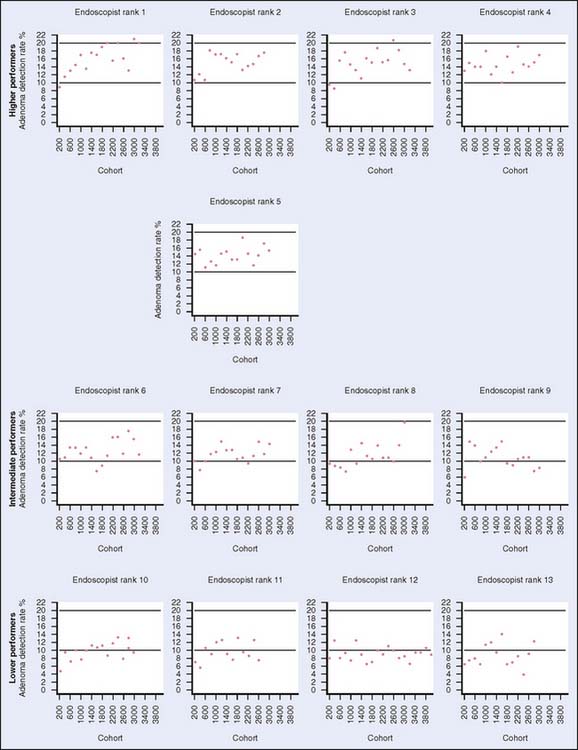

According to the Behavior Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), only 30% to 50% of individuals for whom screening is recommended are currently being screened in the United States. Moreover, the percentage of those undergoing screening varies widely by region within the United States (Fig. 8-2, Table 8-1). Furthermore, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there are approximately 41 million average-risk persons older than 50 years who are eligible for screening.7 Only an estimated 2.8 million flexible sigmoidoscopies and 14.2 million colonoscopies were performed in 2002. To meet the demands if all individuals were to be screened, at least 18 million more colonoscopies would have to be performed annually. To provide more resources, one solution is to increase the number of persons trained in endoscopy. However, ensuring that quality control measures are in place is an important aspect of a screening program. Recent reports in the literature have demonstrated that adenoma detection rates may vary greatly with endoscopist experience such that endoscopists who have performed more than 400 endoscopies were better at detecting adenomas than those who had not8 (Fig. 8-3). If appropriately implemented, regular colonoscopic screening and adherence to screening guidelines may prevent 76% to 90% of colon cancers.9

Table 8-1 Percentage of Adults Aged ≥50 Years Who Reported Receiving a Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) Within 12 Months Preceding Survey and/or Lower Endoscopy Within 5 and 10 Years Preceding Survey, by Test Type

| Test | % | (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| FOBT within 12 mo | 23.5 | (±0.5) |

| Lower endoscopy within 5 yr | 38.7 | (±0.5) |

| Lower endoscopy within 10 yr | 43.4 | (±0.6) |

| FOBT within 12 mo and/or lower endoscopy within 10 yr | 59.1 | (±0.6) |

*Age-adjusted to the 2001 BRFSS population.

CI, confidence interval.

From Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems (BRFSS), United States, 2001; Colorectal cancer test use among persons aged >50 years, United States, 2001. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Rep 52:193–196, 2003, Fig. 1.

Findings on Endoscopic Evaluation

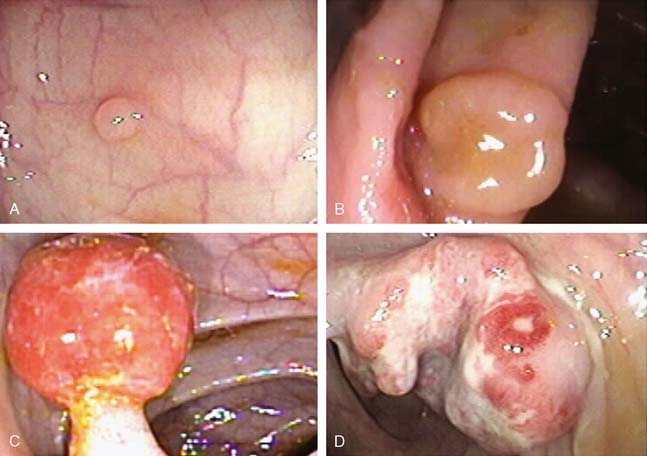

Lesions found on endoscopic examination can be broadly categorized as polyps and nonpolypoid lesions (Fig. 8-4). Polyps are characterized as neoplastic or non-neoplastic. Non-neoplastic polyps are further subdivided into hyperplastic polyps, hamartomas, lymphoid aggregrates, and inflammatory polyps. Those with malignant potential include tubular, tubulovillous, and villous polyps. Serrated and microtubular adenomas as well as invasive carcinoma may also be found.10 Histologically, features indicating a more favorable prognosis include the absence of poor differentiation and the absence of lymphatic or vascular involvement.11 Nonpolypoid lesions have been more difficult to detect, yet make up 30% to 40% of all CRC lesions.12–14 Today’s endoscopic techniques are beginning to incorporate staining and microscopy techniques that further aid in the detection and classification of such lesions. Regarding anatomic distribution, about 50% of polyps are found in the proximal colon, whereas 20% are found distally. Synchronous polyps are found in about 30% of cases. Adenomas and carcinomas, however, have a right-sided predominance that increases with age.15

Screening and Surveillance Tools

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy

The flexible sigmoidoscope is an endoscopic tool that allows visualization of the large bowel to the depth of about 70 cm (Fig. 8-5). The benefits of flexible sigmoidoscopy include lower cost, lack of necessity for full bowel preparation, and no sedation. The preparation for this procedure can usually be accomplished with enemas given no more than 3 hours before the procedure. This modality is often used in conjunction with fecal occult blood testing. This screening combination has been reported to have a detection rate of 76% in contrast to 70% with flexible sigmoidoscopy alone.16

Flexible sigmoidoscopy, although limited in extent of colonic visualization, is associated with decreased morbidity and mortality.17 A large Veterans’ Administration population study by Muller and Sonnenberg18 revealed a 50% reduction in risk of developing CRC (odds ratio 0.55) through endoscopic procedures. This protective influence lasted about 6 years. Others have noted protection sustainable for as long as 16 years.19 Current guidelines set by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Radiology recommend examination by flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years for average-risk persons20 (Table 8-2).

Table 8-2 A Comparison of Flexible Sigmoidoscopy and Colonoscopy in Colorectal Cancer Screening in the Average-Risk, Asymptomatic Person

| Flexible Sigmoidoscopy | Colonoscopy | |

|---|---|---|

| Screening interval in the asymptomatic individual | 5 years | 10 years |

| Age for average-risk screening initiation | 50 years | 50 years |

| Depth of visualization | Distal transverse colon | Entire colon |

| Preparation | Enema, laxative | Liquid cathartic |

| Sedation | None | Light, intravenous |

| Perforation risk | 1 per 10,000 | 1 per 1000 |

The obvious limitation of performing flexible sigmoidoscopy is the depth of visualization, limited mainly to the left colon and part of the transverse colon. In an effort to overcome the inherent hindrance, multiple studies have attempted to predict the potential presence of proximal lesions otherwise missed by this imaging modality by examining distal findings. Advanced proximal adenomas may occur in patients, regardless of the presence of advanced lesions in the distal colon. Advanced distal lesions, however, are indicative of a higher risk of advanced proximal lesions. Imperiale and colleagues21 reported a 2.6 relative risk of advanced proximal neoplasia for patients with distal hyperplastic polyps, whereas patients with distal tubular adenomas or advanced distal polyps had a relative risk ratio of 4.0 or 6.7, respectively, compared with patients with no distal polyps. Furthermore, age greater than 65 years, family history of CRC, villous histology in distal adenomas, adenomas larger than or equal to 1 cm, and multiplicity of distal adenomas are associated with increased risk of advanced proximal lesions.22 In such populations, it may be prudent to proceed directly to total colonic examination through colonoscopy. Despite the potential pitfalls associated with limited visualization, flexible sigmoidoscopy remains a frequently used screening option.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree