8110

Cognitive Syndromes and Delirium

Reena Jaiswal and Yesne Alici

INTRODUCTION

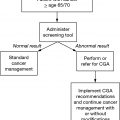

Cognitive syndromes are commonly encountered among cancer patients, with the elderly being at higher risk (1). Factors such as primary or metastatic brain tumors, delirium, comorbid depression, or adverse effects of treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation can predispose patients to developing cognitive deficits (2). Cognitive deficits in older adults heavily impact outcomes in cancer care due to potential impairments in decision making and activities of daily living (e.g., ability to take medications). It is therefore important to systematically screen for cognitive impairment among elderly patients in oncology settings. In the absence of a structured screening tool for cognitive impairment, patients with cognitive syndromes are frequently underrecognized. Once a cognitive syndrome is identified, assessment of the underlying etiologies helps identify reversible and irreversible factors, as well as revising goals of care if needed. This chapter focuses on the cognitive assessment of older cancer patients and reviews the most commonly seen neurocognitive disorders (including delirium) in oncology settings.

DELIRIUM

Delirium is one of the most common and most serious neuropsychiatric complications seen in older adults with cancer. It is defined as an acute change in attention, level of alertness, cognition, and behavior secondary to a general medical condition or medications and is associated with significant distress, morbidity, and mortality (3). In elderly patients, delirium is associated with increased rates of cognitive decline, admission to institutions, increased health care costs, and mortality. The growing data on short-term and long-term outcomes of delirium highlight the importance of screening for it among all hospitalized cancer patients.

Older age and preexisting cognitive impairment are well-documented risk factors for delirium (4). Delirium is characterized by three subtypes based on the patient’s level of psychomotor activity: hyperactive, hypoactive, or mixed (features of both hyperactive and hypoactive). Hyperactive delirium is associated with agitation and hallucinations, whereas patients with the hypoactive subtype 82appear lethargic with slowed movements. In older adults, the hypoactive form may be more common, but is under-recognized (5). Both subtypes of delirium are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in the medically ill and are significantly distressing to patients and caregivers (6). Therefore, timely diagnosis and management of delirium are essential regardless of the subtype.

Assessment for Delirium

The “gold standard” diagnosis of delirium is the clinician’s assessment based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (7) delirium diagnostic criteria. Table 10.1 presents the highlights of delirium assessment in older patients with cancer. Several assessment and rating scales have been developed specifically for delirium, each with its own strengths and weaknesses (8,9). Commonly used delirium screening and assessment tools are reviewed in Table 10.2.

TABLE 10.1 Assessment of Delirium

■ Delirium is an acute change in mental status with fluctuating course, attentional impairment, and disturbed level of alertness, accompanied by cognitive disturbances and/or delusions/perceptual disturbances due to medications or underlying medical etiologies. ■ Clinical features may include psychomotor disturbances, sleep-wake cycle changes, agitation in the form of refusal of care, and affective ability. ■ A timeline of when the symptoms began and how fast they are progressing is helpful in making the diagnosis. Rapid onset of cognitive impairment = delirium; gradual onset and progressive decline = dementia. ■ Look for fluctuations in level of alertness; evaluate patients at different time points over 24 hr. ■ Delirium may present with suicidal ideation, impulsivity, poor judgment, paranoia, and perceptual disturbances, which can increase risk of self-harm. ■ Review the medication list for recent exposure to deliriogenic medications, especially anticholinergic agents, benzodiazepines, and opiates. ■ Conduct a thorough physical exam. Look for signs of infection/sepsis or neurologic deficits. ■ Laboratory and imaging testing should be ordered to identify infectious, metabolic, or endocrine disturbances. ■ Consider neuroimaging in patients with new focal neurologic deficits, concerns for CNS infections, history of primary CNS cancer, or suspected CNS metastasis. ■ Electroencephalography may help to diagnose nonconvulsive seizures as a cause of acute cognitive changes. Generalized slowing on an EEG can be seen in delirium or dementia, not in depression. |

CNS, central nervous system; EEG, electroencephalogram.

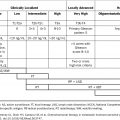

83TABLE 10.2 Commonly Used Delirium Screening and Assessment Tools

Confusion Assessment Method (10) | ■ Most commonly used delirium screening instrument in general medical settings, specifically among older adults. ■ Four-item algorithm can be used to quickly screen for delirium. ■ Requires well-trained raters. ■ Excellent psychometric properties when used by well-trained raters. ■ Cognitive testing is required to assess the cognitive items of the scale. ■ Validated for use in a number of languages. |

Delirium Rating Scale-R-98 (11) | ■ Includes 16 clinician-rated items, 13 for severity and 3 for diagnosis. The rating is applicable to the preceding 24 hr. ■ Successfully differentiates delirium from dementia, depression, and schizophrenia. ■ Administered by trained clinicians. ■ Has excellent psychometric properties. ■ Mostly used for research purposes. ■ Has been validated in different languages. |

Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (12) | ■ Mainly used for assessment of the severity and subtype of delirium. ■ MDAS has 10 items, rated from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), with a maximum possible score of 30. ■ A score of 13 has been recommended as a cut-off for establishing the diagnosis of delirium in oncology settings. ■ A cut-off score of 7 has yielded the highest sensitivity and specificity rates for delirium diagnosis in palliative care settings (1). ■ Has excellent psychometric properties. ■ Distinguishes between patients with delirium, dementia, or no cognitive impairment. ■ Has been validated in a number of different languages. ■ The most widely used delirium assessment scale in oncology and palliative care settings. ■ Physician-rated. ■ Takes about 10–15 min to administer. |

Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (Nu-DESC) (13) | ■ Adapted from Confusion Rating Scale, a former delirium assessment tool. ■ Comprised of five items including: orientation, behavior, communication, perceptual disturbances, and psychomotor retardation. ■ Allows for continuous symptom assessment. ■ Has been validated for use in oncology settings. ■ Administered by nursing staff. ■ Takes about 1–2 min. ■ Has good psychometric properties. ■ Has been validated in different languages. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree